I. SUMMARY

This position paper[i] presents a coherent position on a fair distribution of losses which transfers the burden of the financial crisis on those who caused it, through a return to accountability and a recipe for how to absorb the losses through internationally recognised mechanisms. The paper is summarised as follows:

Move from bail-out to bail-in

- There is a need to move away from the status quo and towards the announcement of official bankruptcy of the banks, a move that needs to be decided by the judiciary.

- Official bankruptcy will mean that the bail-out can stop, and the bail-in can start.

- Lebanon already has a law (Law No. 2/67) which governs bankruptcy which is not being applied.

- Under Law No. 2/67 commercial banks’ board of directors, auditors, and authorized signatories can be held personally liable for the banks’ losses—and that is why the law is not being upheld.

- Should Law No. 2/67 be applied, the assets of those liable—including their foreign assets and post-2019 withdrawals— could well cover the gap in the financial system. But we need to lift banking secrecy to find out.

Distribution of Losses

- Lebanon is not the first country to have a financial crisis, and bail-in must follow internationally recognized standards amended to our situation.

- Lebanon’s situation is not ideal because the BDL did not follow international norms or regulate the banking sector accordingly.

- To be as compliant as possible with international standards, Lebanon must amend the international standard for bail-in called Total Loss Absorbing Capacity (TLAC).

- Any forced conversion of foreign currencies into LBP is resolutely rejected as unlawful and subject to criminal proceedings.

- A TLAC structured distribution of losses will entail

- Wipeout of existing shareholders, estimated around $20 billion.

- Audit of large depositors accounts and wipeout of profits under financial engineering schemes.

- Compensation for large deposits over time through equity in the banks, and clawback mechanisms.

- Protection of small deposits up to 250,000 USD.

- Institution of deposit insurance scheme up to 250,000 USD.

Accountability

- Alongside international standards and Lebanese law, accountability for the crisis needs to dictate how losses are distributed.

- Not all depositors are the same, and those which profited from financial crisis, including through financial engineering schemes should not be treated the same as those which did not.

- BDL Governor Riad Salameh’s lack of adherence to post-GFC international banking regulations, and his place as the head of no less than three oversight bodies, are grounds for his immediate dismissal and reform of banking sector regulations.

- Salameh’s dismissal is also required given that the process under Law No. 2/67 could end up with the BDL governor making the decision to whether banks must be restructured or enter liquidation.

- Hence, lawmakers should introduce amendments to the law to strip the BDL governor of the final say in liquidation and restructuring decisions.

Bank restructuring, restoring trust

- Banks should be restructured in a manner which applies the TLAC distribution of losses and parks bad assets at the BDL to be delt with over time through clawbacks, debt-to-equity swaps, and other mechanisms.

- Banks will try to reject mergers, debt-to-equity swaps or liquidation of certain banks for sectarian reasons, and this should be rejected.

- When the banks are restructured, then we also need to govern the sector so that the BDL governor is not solely in charge of the whole sector and thus there are no checks and balances.

- Only when that happens can there be reforms which allow the sector to regain trust and build modern banking services for the Lebanese and their economy.

II. INTRODUCTION

The country’s ruling elite and banking sector remain determined to avoid taking responsibility for the financial crisis they caused. As a result, depositors are bearing the unfortunate consequences by paying (literally) for their mistakes. Instead of perpetuating the status quo, the application of international best practices, local laws and regulations need to be enforced to guide a fair distribution of the financial losses on culpable stakeholders. Coupled with the IMF’s 3bn $ rescue deal, the application of these laws and regulations pave the way for a transition to a “bail-in” as opposed to the current imposed “bail-out” by depositors. However, their application is hampered by the fact that the BDL and commercial banks have resisted an official declaration of insolvency and bankruptcy. Save for a few cases brought by politically-affiliated judges, the judiciary remains idle in bringing about official bankruptcy. As a result, the BDL and commercial banks are able to continue in the application of a shadow financial plan,[ii] driven by BDL circulars which perpetuate the bail-out of banks by depositors.

Thus just and impartial distribution of losses is imperative for various reasons: (1) to hold the politico-financial class accountable for its mismanagement and futile decisions, (2) to remove the burden of the financial crisis off the shoulders of small depositors, and (3) to pave the way for recovery of the financial sector and the economy. Accordingly, this position paper[iii] presents a coherent position on a fair distribution of losses which transfers the burden of the financial crisis on those who caused it, through a return to accountability and a recipe for how to absorb the losses through internationally recognised mechanisms.

III. REMOVING BARRIERS TO A BAIL-IN

During the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2008/2009, countries around the world faced heavy public criticism for using taxpayer money to compensate losses at banks and financial institutions, also known as a bailout. Consequently, some international and banking regulatory norms were revised/amended to reduce the burden on the public in any future financial crisis. Specifically, a revised Total Loss Absorption Capacity (TLAC) and BASEL III, an international regulatory accord designed to mitigate financial risk, are two international standards relevant to Lebanon which promote conditions for facilitating a bail-in as opposed to a bail-out. Lebanon’s current situation could have been avoided to a large extent had BDL signed up and implemented BASEL III (Basel IV is scheduled for launch on January 31, 2023). However, the BDL resisted calls to reform the banking sector under the false pretext of that the sector was immune to the GFC. As a result, Lebanon doesn’t have any post GFC regulatory reforms to properly cushion financial collapses, let alone protect depositors’ money. As Lebanon doesn’t comply with international regulations related to the distribution of losses, the state’s proposed solution is to finance the losses by selling state assets, gold reserves, and rely on yet to be established hydrocarbon revenues.

Meanwhile, Law 2/67 governing insolvency proceedings of Lebanese commercial banks exists in the Official Gazette[iv]. Under the law, commercial bank’s board of directors, auditors, and authorized signatories can be held personally liable for the banks’ losses. Law 2/67 also clearly states that when a bank defaults, it must enter an insolvency procedure. When the court initiates insolvency proceedings, the bank’s board of directors is removed and their assets frozen for 12 months, while banking secrecy is lifted for them and their close relatives. A committee is then appointed by the court to review the bank’s losses and liabilities and then provide suitable recommendations. During this process, the judiciary investigates the bank’s management (parties mentioned above), and depending on the outcome, the latter can be held liable for their personal assets to cover the bank’s debts. In theory, these assets could extend to foreign assets, meaning funds abroad transferred after October 2019, real estate, yachts and other assets could be frozen and seized over time to pay back debts and deposits. When the court initiates insolvency proceedings, the bank’s board of directors is removed and their assets frozen for 12 months, while banking secrecy is lifted for them and their close relatives. A committee is then appointed by the court to review the bank’s losses and liabilities and then provide suitable recommendations.

To kick-off this process, a defaulted bank must be declared insolvent in court, and local banks have been dodging this confession. Second, upon initiation, if the reviewing committee fails to make an assessment within 6 months, a second committee headed by the BDL government presents the final recommendations to the court. At present, this process would entail that the current BDL governor who has presided over the financial crisis would have the final say on bankruptcy and accountability.

While not ideal, the initiation of bankruptcy should take place alongside amendments to Law 2/67. Doing so would signal that the impunity of a deeply entrenched politico-financial sector can begin to end. It is important to note that ministers, prime ministers, and closely related individuals are shareholders or CEO of banks (As last measured in 2016, political figures have established links to 18 out of Lebanon’s 20 largest banks[v]) and political appointees are part of BDL’s regulatory bodies. The BDL governor also heads the three oversight regulatory bodies within BDL, with his deputies relegated to performing tasks of his own choosing. This ‘double hatting’ practice is prohibited by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), to top global committee of banking supervisory authorities from 28 countries. Insolvency proceedings and a fair distribution of losses are therefore hindered by a tight politico-financial grip that wants to protect its own purse and interests.

The following section presents recommendations that could guide the roadmap of a fair distribution of losses.

IV. BAIL-IN WATERFALL OF LOSS ALLOCATION

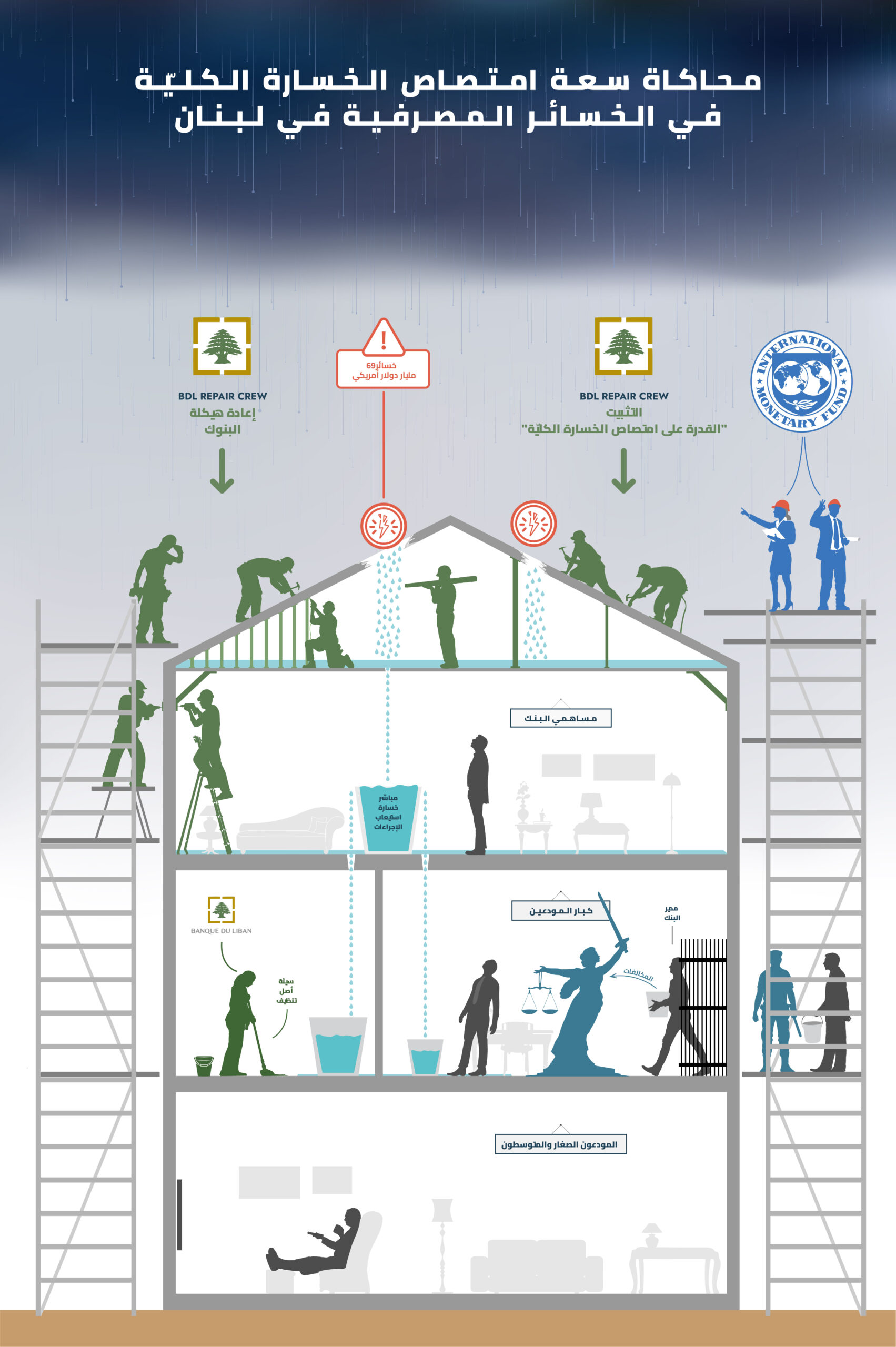

The TLAC process: While Lebanon doesn’t have the exact regulations in place to follow international regulations, it should follow the spirit of TLAC process, otherwise known as the ‘bail-in waterfall’. This international standard aims at an orderly distribution of losses by enabling a bail-in by investors/debt holders rather than relying on bail-out resting on public funds and depositors’ money. The bail-in waterfall under TLAC regulations is explained below and in an infographic (See Annex A):

First, the banks’ shareholders must foot the bill and absorb the bank’s losses to the greatest extent, which in Lebanon’s case, will mean a wipe-out 100% of their shareholdings. Existing bank shareholders and preferred shareholders’ capital was valued at 31 trillion LBP (approx. US$20.6 billion at the 1500LBP exchange rate) in 2021. Under TLAC, if shareholder wipeout doesn’t cover all the liabilities, less senior bank creditors (who are mainly investors holding long-term subordinated debt) absorb the remaining losses by converting their debts into equity shares. In Lebanon however, this step is largely skipped because subordinated debt does not feature heavily in banks’ liabilities.

However, the lack of subordinated debt in Lebanon means the second tier of loss responsibility will be an agreement on large deposits (defined by Lebanon’s Depositors Union and the US FDIC as holding accounts exceeding 250,000 USD). Through the removal of banking secrecy, the source of large depositors’ money can and should be audited before being included in the waterfall of losses, whereas further action and a higher share of inclusion can be adopted in case the source of money can’t be justified. It’s noteworthy that in 2015, the Lebanese banking system had over 1.6 million accounts of which only 1% accounted for 50% of the value of deposits, meaning objections to such an audit being too complex are unfounded. This bail-in of large depositors’ accounts should:

- Start with a partial write-off of oversized profits stemming from the financial engineering schemes implemented by the BDL with selected depositors.

- Converting part of large deposits into preferential shares in restructured banks. This share conversion will form the primary component of their compensation as they will receive preferential dividend payments once the banks start making profits. Large dispositors could also sell these shares once their banks were returned to solid base.

- Clawbacks (explained below) as compensation for large depositors over time.

Even with these measures in place, it may be the case some the losses cannot be covered. Failed banks will have to be merged and remaining bad assets (e.g. non-performing loans) will be transferred to BDL balance sheets. Lebanon had by 2019 a remarkable 63 banks servicing a country of 6 million inhabitants. As per the IMF’s recommendations, banks should be assessed one at a time (instead of the whole financial system at once). Through this process banks that are unable to recover by themselves should do so, while those that are not are to be merged with other banks.

The (not so) implicit sectarian nature of banks, means any systematic bank-by-bank restructuring banking threatens the prized element of sectarian financing. Banks which have historical links to sects (e.g. BBAC, Bank Med, etc.) will need to be diluted or merged with other banks, something which will most likely be resisted by sectarian forces in the country. In particular, there is a view that debt-to-equity conversions of large deposits stemming from Shites based in Africa would tip the scales towards ‘Shite ownership’ of banks. These unfounded and regressive principles should be rejected under the pretence of financial recovery, the transition to a non-sectarian society (already underway), and a future banking system that is not based on sectarian financing but rather sustainable and equitable growth fuelled by a well-regulated banking sector (see below). Thus, restructuring of banks, merged or not, should shift towards a banking system that protects depositors, meets the needs of domestic clients, spurs local growth, and relieves the national debt burden.

Clawbacks

Post GFC-reforms have further protected depositors with clawback provisions, which impose financial accountability on key decision-makers within banks. Clawbacks compel bank management (board of directors and senior staff) to pay compensation and penalties for making decisions that did not benefit the bank and discharging their corporate duties inadequately, even after their tenure is over. The money recouped from this process should then be allocated as an additional stream of capital to meet the bank’s losses and most importantly to compensate large depositors as much as possible for the haircut on their deposits. In the Lebanese case, clawbacks are obviously unheard of and do not exist under the Lebanese banking system yet. The new parliament and the IMF should push for the application of clawbacks under a non-compromised judicial system. A myriad of dreadful bank management decisions should be accounted for. This includes the transfer of more than $6 billion[vi] abroad under the imposition illegal capital controls preventing ordinary depositors from accessing their savings, as well as the accumulation of bonuses and commissions paid out to bank management before the onset of the 2019 financial crisis. Clawback provisions will need to be legislated by parliament and implemented by the BDL through circulars.

Forced conversions and depositor insurance policies

Forced conversions of depositors’ money from USD to LBP at a devalued rate must end and lirafication of foreign currency deposits cannot be used as means to cover the banks’ losses. Depositor insurance policies should also be implemented to protect depositors’ money in the event of ban failure and the bank’s inability to pay its debts. The current level of coverage provided in Lebanon is far too low (75 million LBP), and higher insurance floors would have reduced the rate of panic withdrawals, which have somehow contributed to the crisis.[1] In the United States, deposits are insured for up to $250,000 in savings, and Lebanese regulations should require similar safeguards in the future.

At present, the NIGD (National Institute for Guarantee of Deposits) in Lebanon is governed by the ABL, which is a clear conflict of interest. The new parliament should advocate for an independent organization not controlled by ABL or any other politico-affiliated organization to guarantee the fair protection of depositors and to avoid disruption by political considerations. Options include reform of the NIGD as a institution similar to the US FDIC, which is funded by premiums that banks and savings associations pay for deposit insurance coverage.

V. ANNEX A: BAIL-IN WATERFALL