Passing a capital control law shouldn’t only be a tool to appeal for international aid while preserving underlying corruption but should endorse structural economic reforms that are deep-rooted within a holistic financial recovery plan.

I. SUMMARY

This position paper1 presents a coherent position on the latest capital control draft law as a tool to a solid and fairer control of deposits flow, limiting corruption and increasing accountability. The paper is summarized as follows:

The proposed devious law holds many flaws:

- The latest draft law explicitly grants exemption to the bank’s financial crimes, in ongoing or future lawsuits. The amnesty is guaranteed in local and foreign jurisdictions and also absolves banks from any obligations to pay compensation and to be held accountable to the current illegal capital controls. This seems to be the intended purpose of the law rather than a true attempt to begin the reform process.

- The latest draft law, if passed in its current fashion, will consecrate in law the immoral discrimination between depositors by adopting distinctive measures between the “old” and “new” foreign currency in the banking system. This abuse obliges depositors to unfairly foot the bills of losses while witnessing the dramatic decrease in their savings’ value.

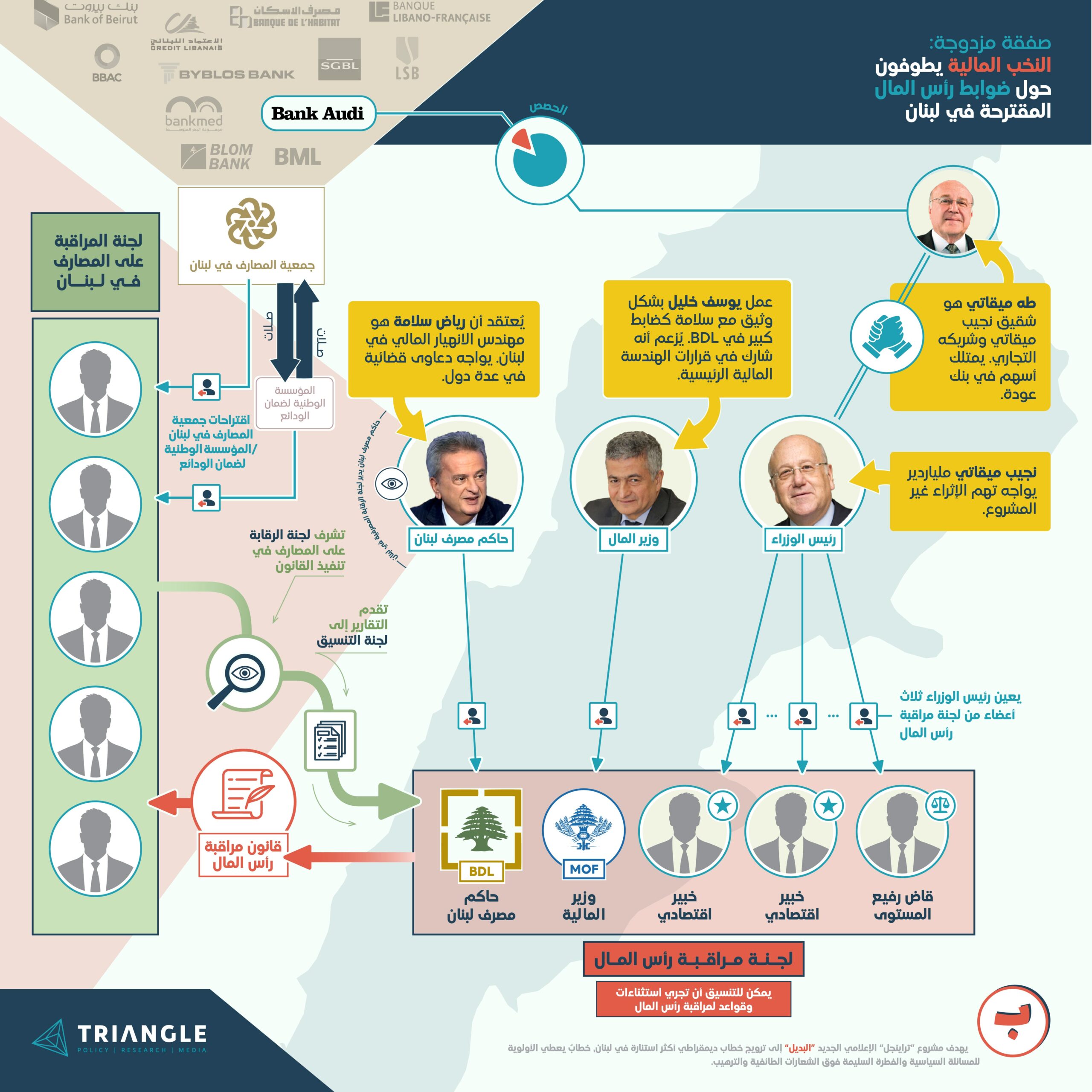

- The membership structure of the capital control committee is rife with conflicts of interests including, the BDL governor, the Minister of Finance, oversight bodies (the BCCL & an assigned entity within BDL ) and the appointment of non-governmental members who are also politically compromised and connected to the banking sector.

- The capital control committee’s power extends beyond overseeing and implementing capital controls while deciding transfer thresholds and currency and exemption categories

- Capital control exemption categories are inaccurate and ambiguous, allowing boundless manipulation, corruption and clientelism.

- There is no action path or mechanism to object and file appeals to the commission’s decisions, leaving it to operate with complete freedom.

- The suggested implementation and renewal timeframes are not rooted in any solid and transparent financial reporting mechanisms.

Required adjustments:

Below is a list of suggestions to allow a fair implementation of capital control:

- The committee’s members should be politically independent. Its members should be elected through well-defined transparent procedures. Specific nomination, selection and election procedures should be included.

- The committee’s oversight bodies can’t be related, either directly or indirectly, to any of its members.

- A well-defined operational framework should be included to dictate the committee’s area of authority, but mostly limit it within a clear scope.

- Exemption categories, defined and ruled over by the committee, should be well rigorously described.

- Withdrawal limits should be fluid within specific timeframes, and the setting withdrawal monthly threshold shouldn’t be purely in the hands of the CCC. A justified gradual lift of monthly withdrawals limit should be described with its relative timeframe.

- Restrictions on domestic transfers should be loosened and lifted. The law should create conditions allowing to gradually lift all restrictions.

- The activation of new accounts should be allowed. The law should focus on limiting the outflow of money and not its domestic use.

- Banks should definitely not enjoy retroactive amnesty, of any kind.

- In fact, the capital control legislation should apply retroactively to October 17, 2019, facilitating the identification and prosecution of those who transferred money abroad after that date. Doing so would also require appropriate amendments to the banking secrecy legislation. The latest banking secrecy legislation doesn’t have a retroactive aspect towards past transactions. The identification of capital flight after October 2019 for a fairer capital control should jointly go with an amended banking secrecy law.

- The law needs to sequence capital control lifting based on properly defined economic reporting and analysis to assess its efficiency and impact with regards to economic progress and the balance of payments.

II. INTRODUCTION

Well-designed capital controls are crucial to Lebanon’s financial recovery. They can limit capital flight, reduce the fluctuating depreciation of the LBP and the decline of foreign exchange reserves of the BDL, among other benefits. Capital controls are also an essential condition to access IMF 2 funding. However, Lebanese depositors have been under non-regulatory and non-legitimate capital controls since October 2019. Banks, under the orders of BDL, have been and are still arbitrarily restricting customers’ access to their savings, through different measures and decisions that vary between local banks. These scattered capital controls, which have no constitutional or legal legitimacy, are facilitating rampant discrimination between well-connected elites and most other depositors, instead of pushing the country towards sound economic reforms. Lebanon witnessed a mass exodus of capital outflow in the midst of capital restrictions and bank closure. Capital flight of connected depositors amounted close to $6 billion between 17 October 2019 and 30 January 2020.

The latest draft law seeks to legitimize the current practices, exempt banks from any ongoing or future prosecution in court, while giving unbounded power to a biased committee which decides how the law is applied. The Lebanese politico-financial decision makers seek and push for a retroactive aspect of a law when retroactivity serves their benefits (capital controls), but refute it when it doesn’t (lifting banking secrecy). The currently enforced measures are therefore used as an appeal for international aid and tool to preserve rampant corruption rather than a key pillar within a wider integral economic recovery plan. Accordingly, this paper highlights the underlying fraudulent flaws of the latest capital control draft (30 March 2022), while providing a coherent position on how capital controls can be implemented to shoulder the country’s financial recovery while protecting depositors’ rights.

III. FLAWS OF CURRENT LAW

- The illegal turned legal:

Past, present, and future amnesty:

Article 12 of the latest draft explicitly grants amnesty to Lebanon’s banks, BDL, financial institutions and even the state to any ongoing or future prosecution concerning illegitimate capital controls imposed since October 2019. Immunity applies no matter the nature of the lawsuits, in local and foreign jurisdictions, and even includes any decision that can be appealed in the future. Therefore, this latest capital control law will shield banks retroactively from all ongoing and future litigations. The amnesty clause absolves banks from any obligation to pay compensation, and to be held accountable for their illegitimate capital control practices. Such a draft bill cannot pass: it legalizes the arbitrary obstructive practices adopted by the banks forbidding people their righteous access to their own money. It also dissolves the judiciary’s power and renders justice idle within the politico-financial grip.

- Preserving “reforms” in the hands of the corrupt: the Capital Control Committee

Capital Control Committee Members:

Article 3 of the latest capital control draft law designates a Capital Control Committee (CCC) responsible for making amendments to the law, ruling on exceptions, and submitting quarterly reports to the Cabinet. The CCC is constituted of the BDL governor, Minister of Finance, two economic experts and a high-ranking judge, and the latter three figures are appointed by the prime minister. The BDL’s governor and the Minister of Finance are on this decisive committee which has high discretionary power, despite their alleged personal culpability for Lebanon’s economic collapse, preserving the solid politico-financial grip on depositors’ money. The selection of non-governmental related members (economic experts and high-ranking judge) is also not transparent and very far from impartiality, compromising any independence from political authority. Article 3 only mentions that the prime minister picks the two economic experts and the high-ranking judge without specifying any selection criteria or area of expertise, except the required level of the judge. Article 3 also doesn’t provide specifications guaranteeing that these members are impartial and politically independent/unbiased.

Operational framework and accountability:

The draft law fails to indicate the rules and provisions the CCC will be subject to .Article 10 states that the Banking Control Commission of Lebanon (BCCL) and the BDL are responsible for overseeing the law’s implementation, overlooking relevant decisions and regulations, and reporting violations by Lebanese Banks. The BCCL – which is one of the two main regulatory bodies embedded within BDL – is a five-member commission, including members from the Association of Banks in Lebanon. It includes delegates from the Ministries of Economy and Finance. Hence, ministerial representatives provide direct, systemic political influence over the BCCL. The Association of Banks in Lebanon (ABL) elects one member, and wields power over another BCCL nominee, that is formally made by the National Institute of Guarantee for Deposits (NIGD), given that the ABL holds a majority stake in NIGD management. BCCL also always works in close coordination with the BDL governor, even though BCCL is meant to enjoy institutional independence (See Figure 1).

The daft law also doesn’t provide any framework of accountability in case the CCC fails the proper implementation of the law. Article 11 only describes the penalization imposed on every person in case of violations of the law, or if they provide incomplete or inaccurate data or information. It therefore gives the CCC flexibility in complying and implementing the law.

Hence, if passed in its present form, the capital control law would see the nation’s rapacious politico-banking elites wield even more control over narrow interests.