EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Lebanon’s State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) are in critical condition, mired in mismanagement, financial turmoil, and systemic inefficiencies. The lack of a legislative framework defining SOEs and their governance has fostered ambiguity surrounding oversight and accountability. The decentralised ownership model, ostensibly managed by individual ministries, has masked an alarming conflict of interest whereby these ministries simultaneously regulate and own these enterprises. This clearly contravenes international standards and highlights severe governance issues. Consequently, SOEs consistently rank amongst the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) top priorities for immediate action in Lebanon.

The IMF’s June 2023 report sounded an ominous warning to the Lebanese government: without structural reforms to SOEs, Lebanese living conditions will further deteriorate given the cascading impact on public services. Now, over seven months have passed, and ministerial promises to the IMF to appoint regulators, conduct audits, and survey institutional governance practices remain unfulfilled.

Instead, Lebanon’s current caretaker ministers have continued in a well-established tradition whereby SOEs are a leading tool of corruption in the state. Ministerial priorities include maintaining nepotistic-patronage networks, centralising of authority within their office, and blame shifting for deficiencies in utility services. As a result, they have neglected urgent reforms to enhance the provision of basic public services in an equitable and transparent manner.

In the electricity sector, the history of Électricité du Liban (EDL) reveals a tale of persistent misallocation of funds, inefficiency, and resistance to external audits, leading to staggering financial losses, amounting to more than US$40 billion of Lebanon’s public debt by 2018.1 The turmoil reached a peak amid Lebanon’s ongoing financial crisis, with electricity tariffs proposed but failing to address the core issues, leaving citizens grappling with daily power cuts. Indeed, energy poverty is now prevalent across the country, according to research by Human Rights Watch. Lebanon’s environment, as well its inhabitants’ health and wealth, have also paid the price.

Telecoms SOEs, Ogero, MIC1 (Alfa), and MIC2 (Touch), while generating substantial revenue, suffer from governance challenges and financial mismanagement. Regulatory authorities, mandated since 2002, are non-existent, with ministries assuming their roles, further contributing to an abysmal global ranking in governance and regulation. A scathing report by the Lebanese Court of Audit, published in April 2022, documented the misallocation of public funds from these SOEs and legal violations by the Ministry of Telecommunications (MoT).

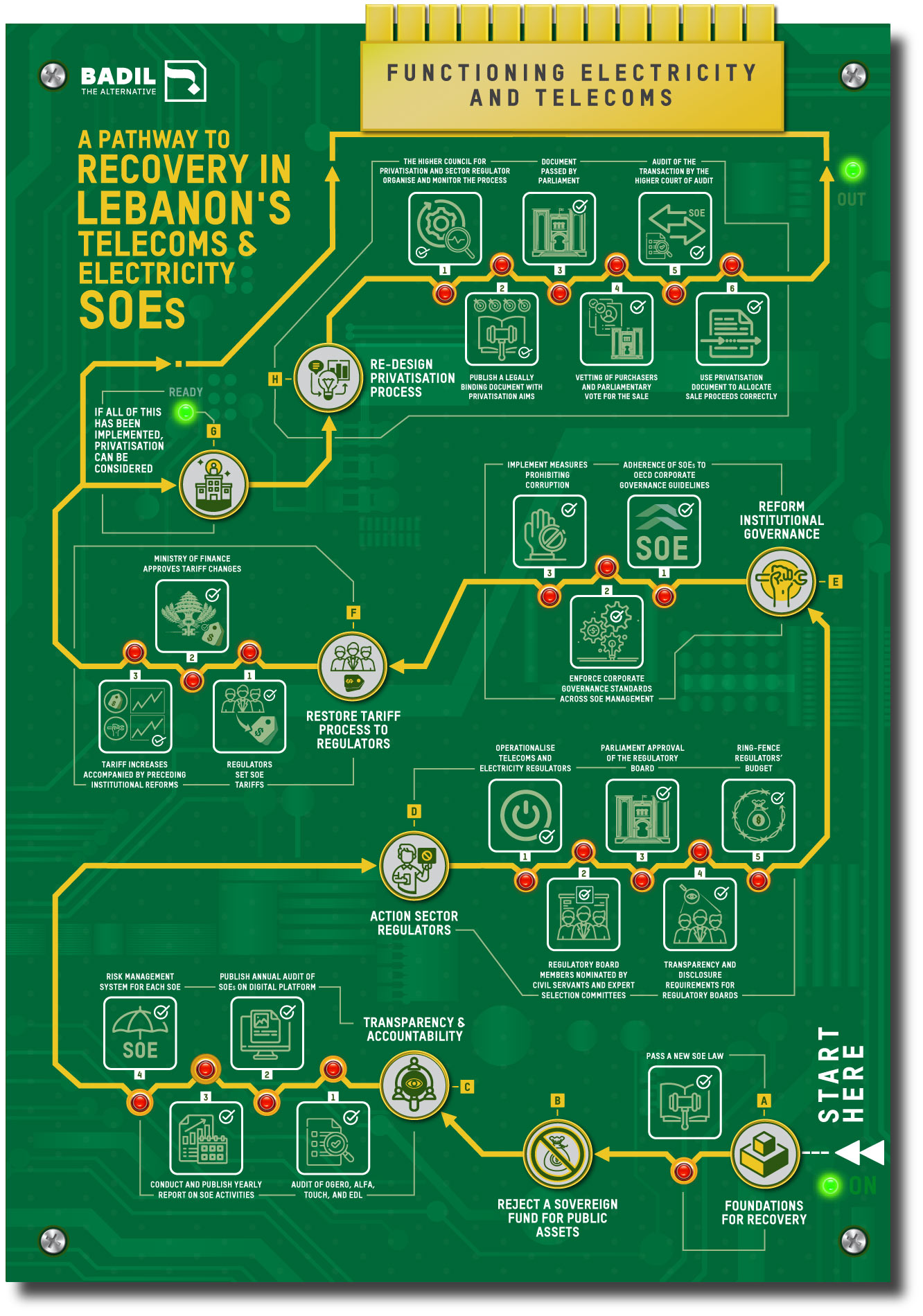

First and foremost, transparency and accountability measures, including external audits conducted by reputable international firms, must be instituted, buttressed by an empowered Higher Court of Audit. The appointment of independent sector regulators, adhering to OECD standards, would provide a much-needed separation of powers, ensuring impartial decision-making.

Institutional governance reforms, inspired by OECD Corporate Governance Guidelines, are essential for SOEs to function independently and transparently. The restoration of tariff-setting authority to regulators would prevent erratic increases and align costs with market conditions. However, tariffs alone cannot salvage the sectors; a comprehensive overhaul involving annual audits, regulatory activation, governance reforms, and a new SOE law are imperative.

The prospect of privatisation, though a potential solution, requires meticulous planning. The absence of a national strategy, a sound regulatory environment, and anti-corruption frameworks necessitates a cautious approach. The Higher Council for Privatisation, augmented with regulatory oversight, should guide this process, ensuring the proceeds are allocated transparently and in line with public policy objectives. What is clearly not in the public interest, however, is the so-called ‘Sovereign Fund’ being suggested by various politicians and the banking sector, which would see state assets used to cover liabilities to commercial banks.

Amid a crisis with inflation at approximately 252 percent and currency devaluation of 90 percent, SOE reform may not seem like an immediate priority. The truth of the matter is, however, that SOE reform sits at the heart of Lebanon’s economic recovery precisely because these institutions are the root of the debt problem and clientelism in the public sector. In tandem, both aspects of SOEs sustain the current crisis and elite capture of the state. In short, without true reform of SOEs there is little hope Lebanon will ever truly recover from its current predicament, much less provide basic services to its people.

INTRODUCTION

A state-owned enterprise can be broadly understood as a publicly owned entity operating with administrative and financial autonomy, partially or totally government controlled, and engaging in commercial or economic activity, as defined by the IMF. In Lebanon, there are 22 SOEs according to this criterion, spanning from public service providers to commercial enterprises. Lebanon’s SOEs are not, however, officially defined or itemised in existing legislation, contributing to ambiguity regarding oversight and accountability.

Lebanon’s SOEs presently operate under a ‘decentralised’ ownership model, according to Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) criterion.2 In this framework, individual ministries are tasked with state ownership and management of each enterprise. However, this system is not explicitly clarified in existing legislation, leading to ambiguity and tensions over governance and management of these institutions. Meanwhile, where active regulators are absent in Lebanon, the relevant ministries often undertake both regulatory and ownership functions for SOEs under their purview. This dual function directly contradicts international standards and reflects a significant governance issue.

The reform of Lebanon’s SOEs necessitates a balanced strategy that tackles both the underlying issues affecting enterprises across the board while also offering tailored approaches to addressing the specific challenges of each institution. Collectively, a new SOE law would outline a clear ownership strategy and thereby establish key objectives, oversight, and management principles, as per IMF recommendations issued following their visit in June 2023.

The SOEs active in Lebanon’s electricity and telecommunications sectors are often considered to be polar opposites in regard to functionality, given the multi-billion-dollar losses the former has for decades incurred and the relative profitability of the latter. Both, however, suffer from profound systemic and institutional challenges that urgently require reform to improve the quality and costs of the services they provide Lebanese. Brief background case studies on both sectors are thus provided below, with the subsequent recommendations acting as examples of the public benefit that could be arrived at from reforming the entire body of Lebanese SOEs.