As with so many of its national tragedies, Lebanon’s disorderly default on US$31.3 billion of sovereign Eurobonds in March 2020 was preventable but detonated as a result of the usual mix of personal greed, outright incompetence and the corrosive manipulation of powerful foreigners. With new data available and some of the actors directly involved finally willing to talk, a fuller picture of a particularly shameful episode in Lebanon’s modern history is now available.

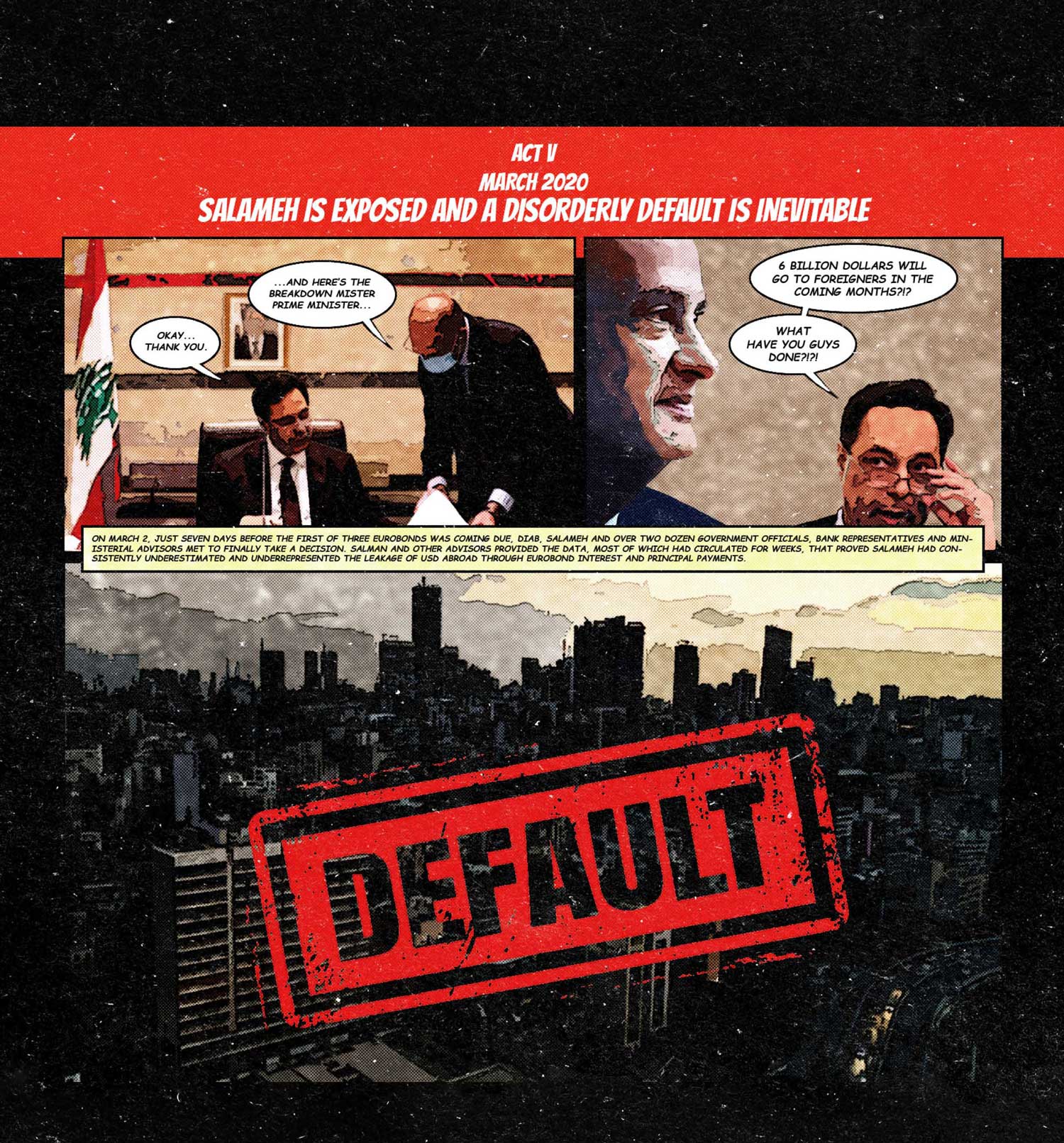

On March 16 2020, Lebanon defaulted on a US$1.2 billion Eurobond. This much, we all know. However, this deceivingly simple sentence does not come close to conveying the true scale of the tragedy that has befallen the country. Nor does it expose any of the events that led to the fateful decision which, given Lebanon’s massive debt, could arguably not have been avoided but, surely, could have been taken in an orderly fashion.

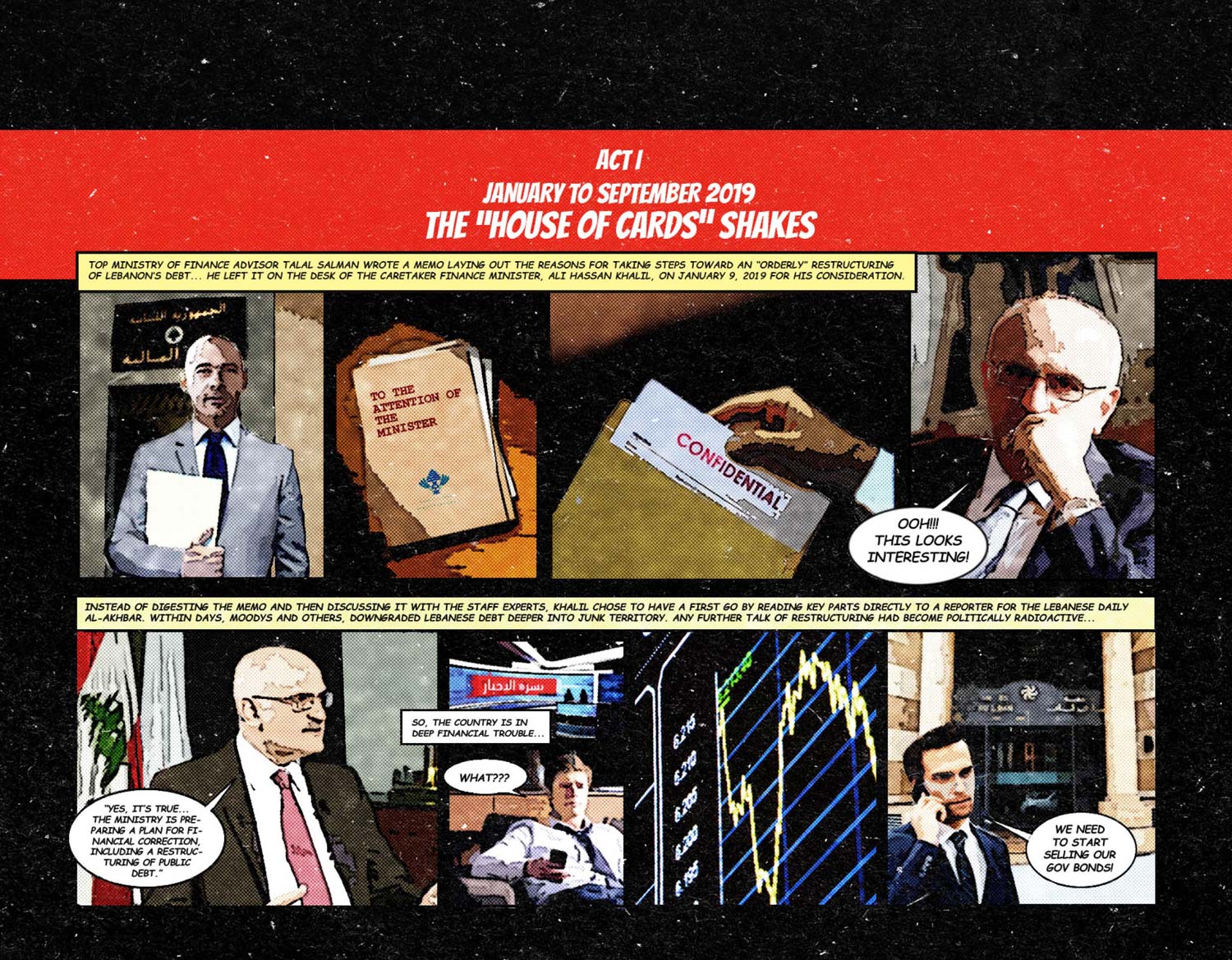

Moreover, the plain fact that Lebanon was not able to repay a loan tells us nothing about the shocking incompetence of a finance minister who decided to share a confidential memo on debt restructuring more than a year before the default, not with his staff but with the press, prompting Moody’s to launch an immediate downgrade of the country’s credit rating and effectively suspending an already badly belated treatment effort.

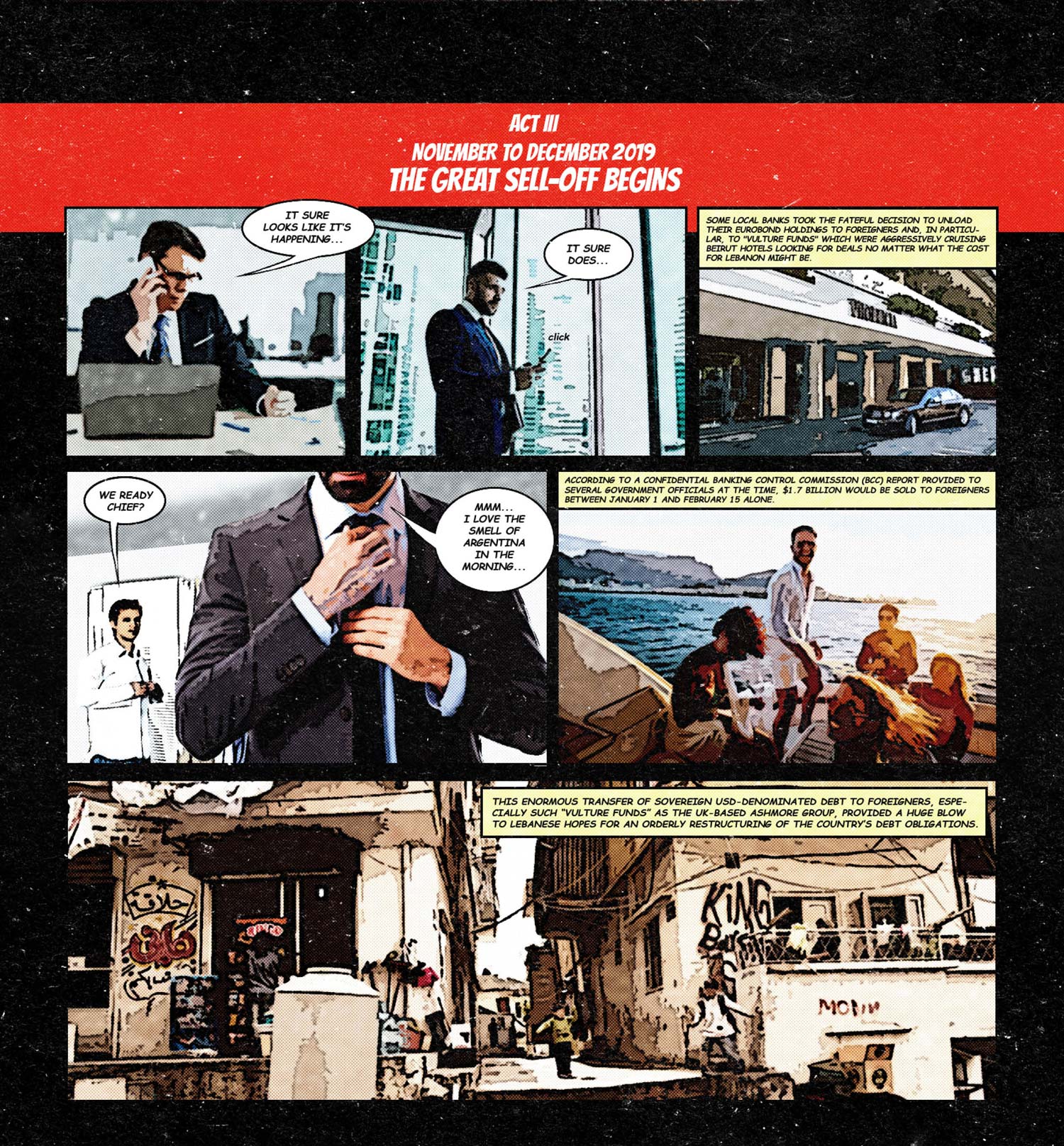

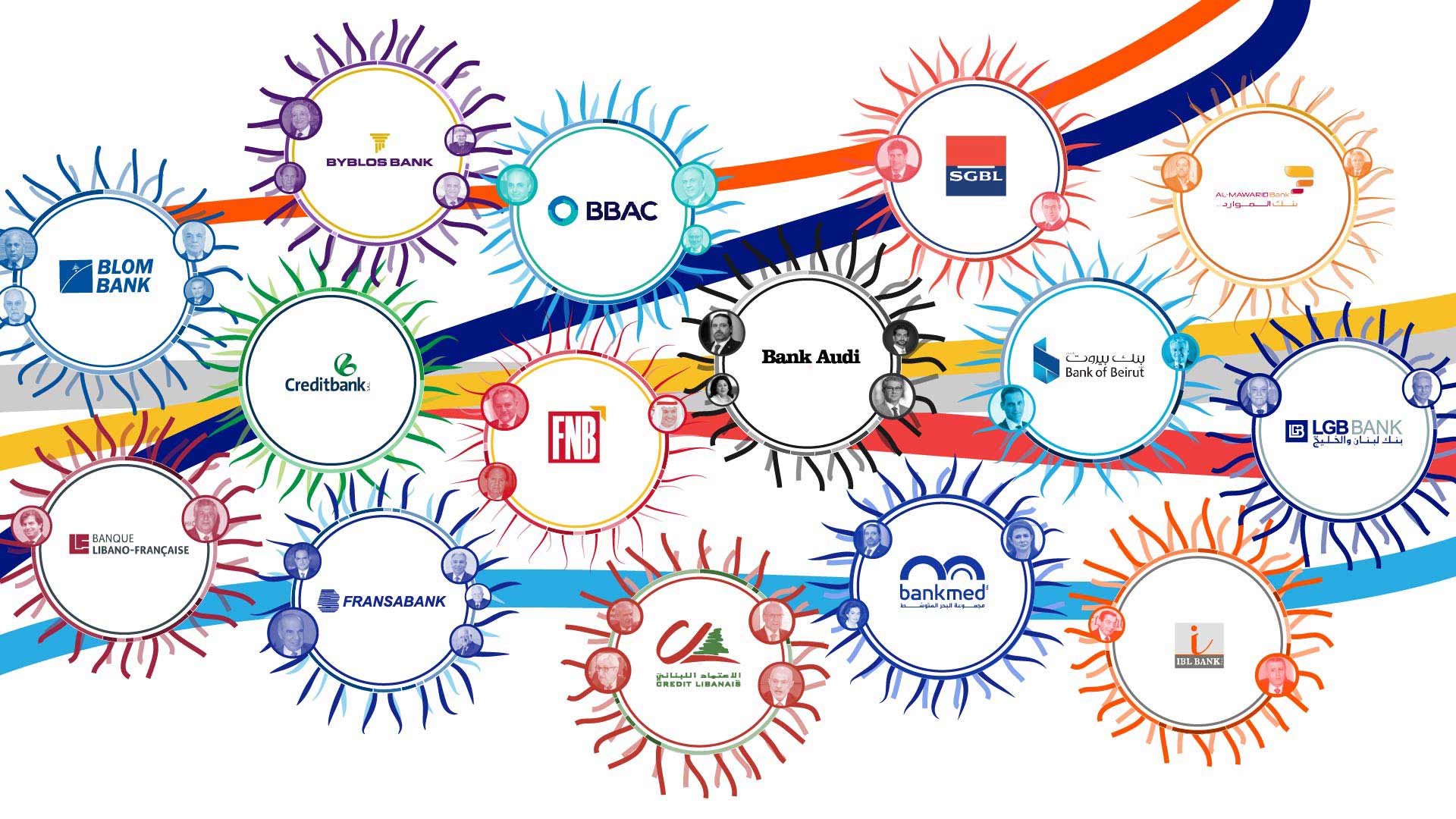

It also fails to fully articulate the ruthlessness and greed of Lebanon’s banks both before and after the default. Pushed by top management and their largest depositors – both hungry for cash to flee a deepening national crisis – the banks did not hesitate to sell Eurobonds into foreign hands, knowing perfectly well that doing so would severely weaken the government’s negotiating position and hamper the prospect of a debt restructuring.

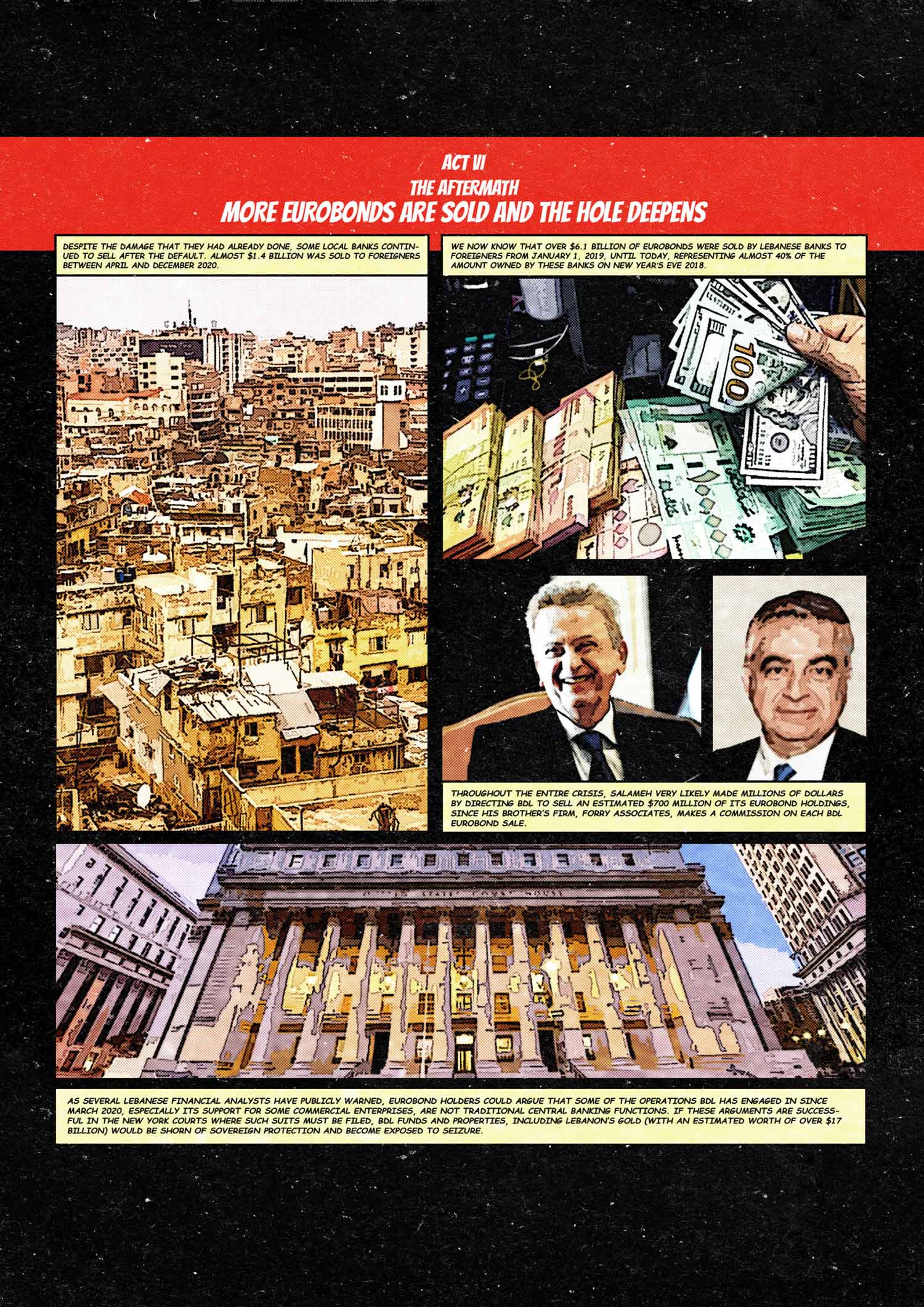

Indeed, most media have long assumed that “the great sell-off” only started in early 2020. It has now become clear that Lebanese banks already sold up to US$1.2 billion in Eurobonds to foreigners between January and October 2019. It did not stop there. Another US$3.5 billion in Eurobonds was sold between the October 17 uprising and March 16, 2020 – the day of the default. Even then, it did not stop.

Lebanese banks happily continued selling after the default, unloading another US$1.4 billion in Eurobonds before the year’s end. In total, local banks are thought to have sold over US$6.1 billion in Eurobonds, which amounts to almost 40% of what they owed before a confidential note on debt restructuring reached the finance minister, who thought it a good idea to digest it by reading it directly to a newspaper reporter.

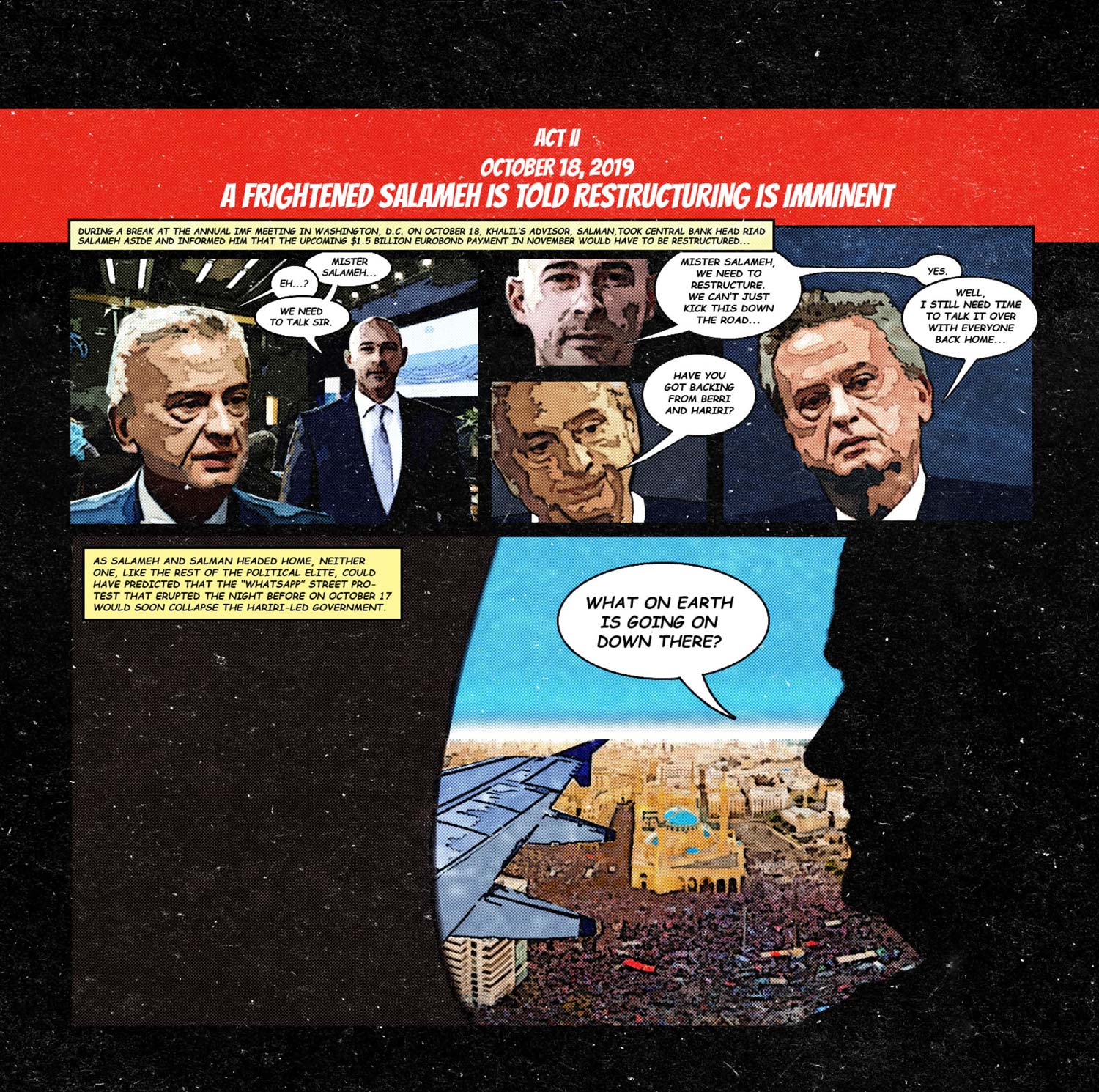

Incredibly – though certainly less so in retrospect – even the Lebanese Central Bank (BDL) got in on the disgrace. Although Riad Salameh was well aware that Lebanon was dangerously short on US dollars and a debt restructuring was back on the political agenda, the BDL Governor in November 2019 insisted on paying a US$1.5 billion Eurobond, as well as US$632 million in interest.

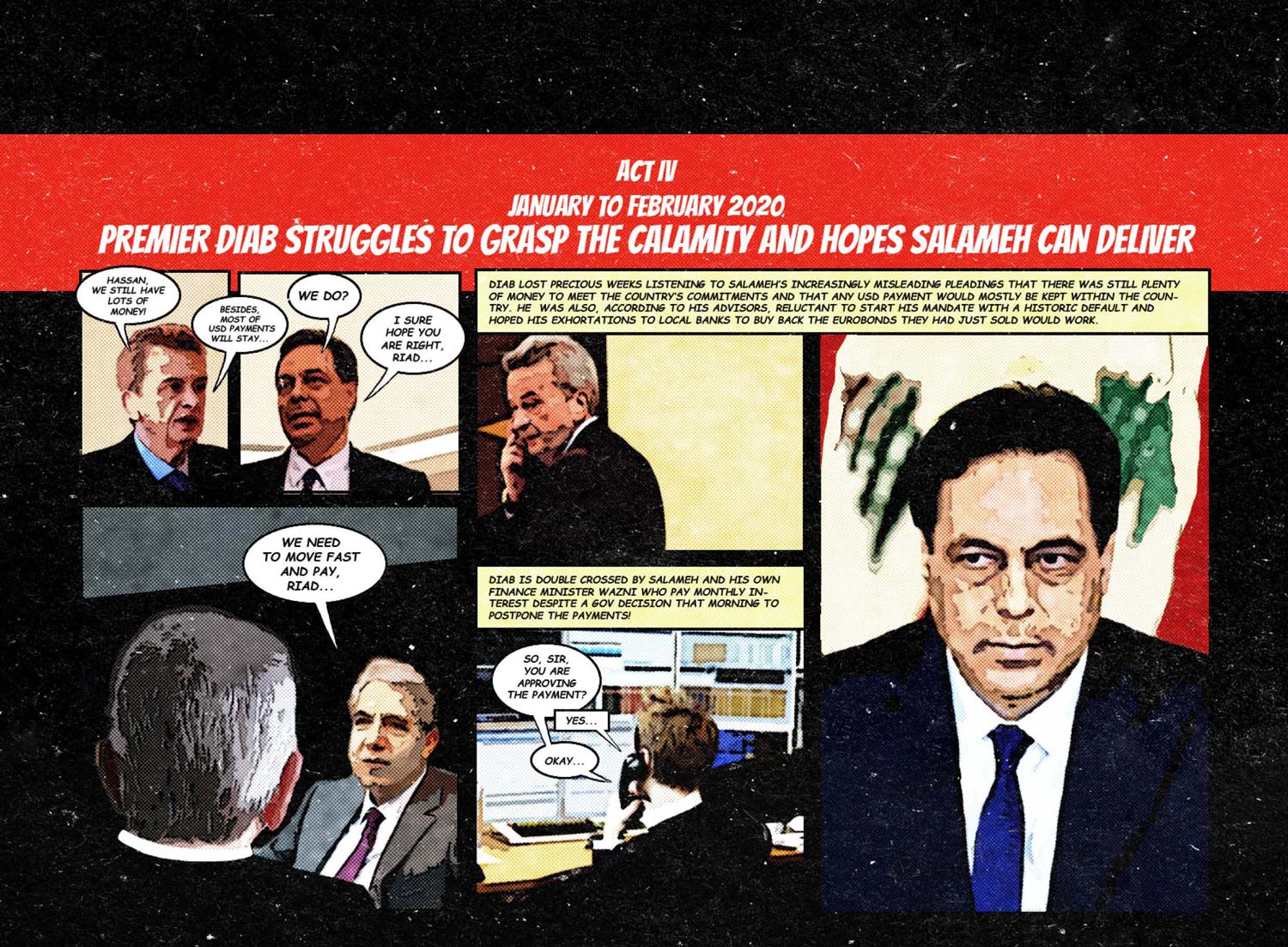

In the months that followed, he consistently downplayed the effects of the accelerating Eurobond sell-off to foreigners, pleading with government policymakers, like the inexperienced new premier, that the “leakage” of precious US Dollars would be minimal.

Following the default, he directed the BDL to sell some US$700 million in Eurobonds, thus further diminishing the Lebanese government’s bargaining position, while he and his family arguably netted millions in secret commissions.

As a result, Lebanon is no longer a master of its debt destiny. Foreigners hold more than US$17 billion in Lebanese Eurobonds and claim to exercise veto power in 40% of all of the country’s Eurobond series. Among them are the so-called “vulture funds,” which purchase distressed debt, often significantly below market value, have no interest in any nationally sound debt restructuring and seek to recover the bonds’ full amount, plus interest, often through draining litigation.

What’s more, foreign Eurobond holders could argue that some of the operations BDL has engaged in since March 2020 cannot be considered traditional central banking functions. If such arguments hold in court, BDL funds and properties – including Lebanon’s gold reserves worth an estimated US$17 billion – could be exposed to foreign seizure.

On March 16, 2020, Lebanon defaulted. It is a seemingly simple phrase that does not do justice to the world of suffering and betrayal it conceals. The Great Sell-Off, in six acts and stunning detail, shines a light on what went on before, during and after that fateful day.