When over 2,000 tonnes of ammonium nitrate exploded on August 4 2020, the ensuing tragedy made global headlines out of an unsettling reality: the Beirut Port has long been a hotbed of criminal activity and gross incompetence. For decades, endemic corruption has siphoned off the port’s financial profits, enriching politicians and their cronies at the wider community’s expense.

In addition, disastrous urban planning decisions have hopelessly isolated the Beirut Port, cutting it adrift from the city with a multi-lane highway and – since August 2020 – shattered, unrestored buildings.

Announced in February 2022, a World Bank-sponsored redevelopment plan could finally turn Beirut Port into both an economic powerhouse and vibrant community space.[1] Unfortunately, early signs suggest that the proposed planning and regulatory reforms risk entrenching the same corrupt management and practices that brought the port to its current nadir.

What’s At Stake

The proposed port redevelopment will help shape the financial and social prospects of the city moving forward. Unhampered by corruption, the Beirut Port could perform a crucial role in driving Lebanon’s recovery from the current, unprecedented economic crisis.

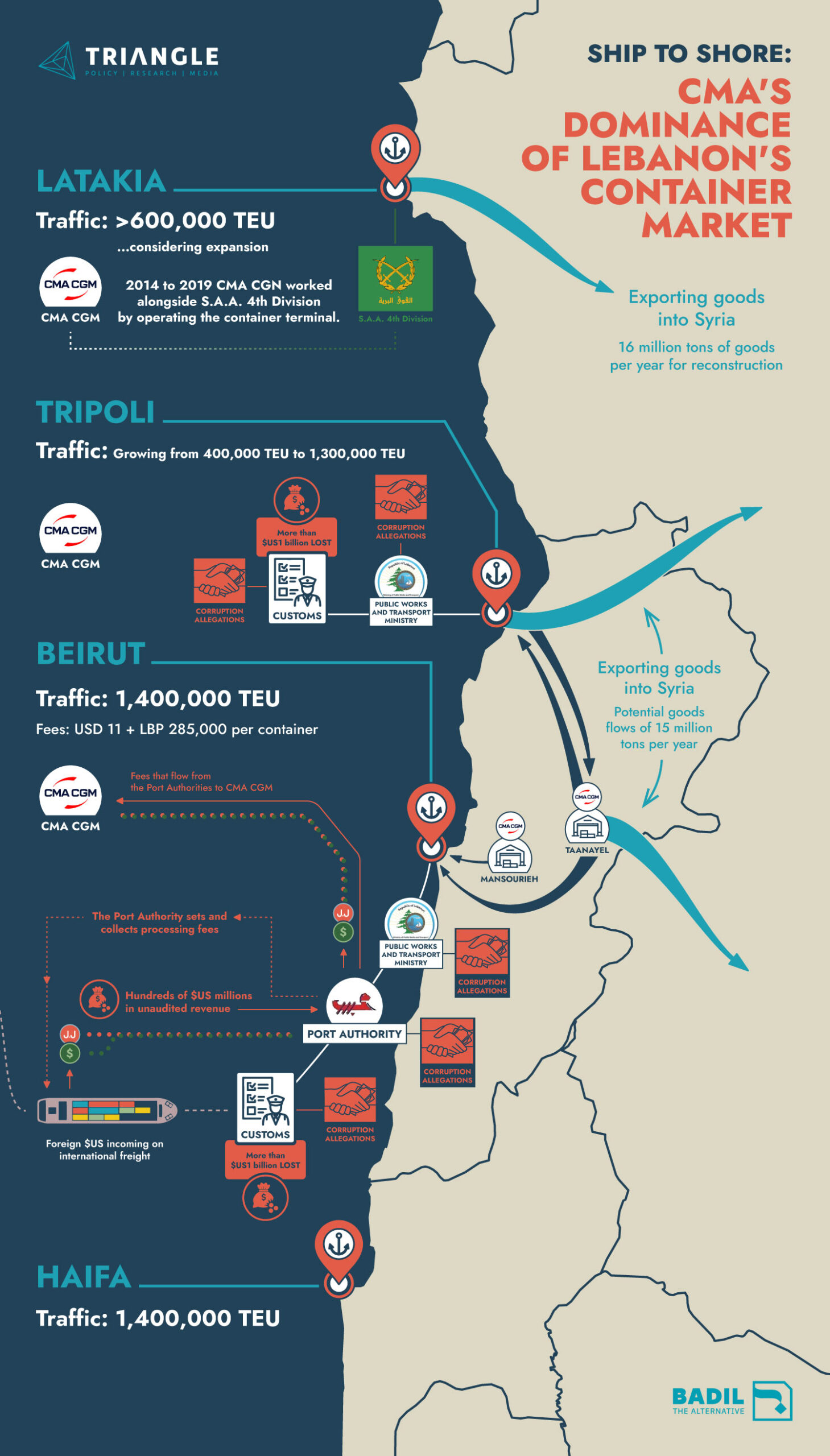

The port’s full capacity of 1.4 million Twenty-foot container equivalent units (TEU) gives Beirut the same maritime freight capacity as Haifa, a key rival Eastern Mediterranean port, and more than double the capacity of Latakia – another competitor port. When combined with the projected 1.3 million TEU capacity of Tripoli Port, shipping through Lebanese ports remains an attractive option for Mediterranean shipping industry. The increased revenues from container shipping alone through a well-functioning Beirut Port are estimated to be worth US$175 million per year. [2]

Lebanon is also well positioned to benefit from increased trade to the region’s interior countries – for example, through the eventual reconstruction of Syria. Leveraged correctly, these commercial opportunities could stimulate more jobs and sources of income for Lebanese households – especially if the international community pushes for transparent revenue management and good governance. [3],[4]

More coherent urban planning could also confer considerable social benefits on the city of Beirut, by better utilising the port’s central location. Professor at the School of Architecture, Balamand Univeristy, Sylvia Yammine argues that the new Beirut Port master plan should focus on “moving the city to the water” through various urban planning strategies. These include providing informal spaces for performances and events, creating walking paths and promenades, preserving the port precinct’s architectural identity, and allowing more green space.

In Yammine’s view, these community-building activities can exist while respecting and facilitating the port’s commercial functions. “[The master plan should] share the use of water, and the waterfront, between urban and port functions,” she said.

USAID has called the process of reforming the Port of Beirut’s governance as a “litmus test for Lebanon’s political classes’ will to undertake broad-based reforms that benefit the Lebanese economy and welfare of the Lebanese people.” [5]

Box: Who’s Doing The Planning?

The World Bank has awarded the contract to prepare the masterplan and vision for the port to a consortium led by Lebanese firm Khoury Consultants and the international engineering consultancy Royal Haskoning DHV. Among other tasks, the consortium has been tasked with preparing an “optimal port sector strategy that best serves the community, promotes complementarity among ports and logistics infrastructure, increases trade, enhances Lebanon’s competitiveness in the region and positions the country as the logistic hub in the region.”[6]

However, World Bank communications seen by The Alternative indicate the bank did not shortlist a major potential bidder for the masterplan – Hamburg Ports Consulting (HPC) – to bid on the tender on the grounds of lacking “relevant experience and capability”. HPC is one of the world’s most well-established and renowned port consultancies, and has conducted more than 1,700 port-related projects in 130 countries over 45 years.[7]

For more than a year the HPC-led consortium has run a well-publicised campaign to create a port vision based on public interest development and independent transparent financial management – including open source assessments of their draft masterplan, as well as a platform calling for civil society input.[8]

The HPC plan – already presented to the Lebanese government – proposed redeveloping the precinct by transplanting much of the port’s current operations outside of the city centre. The suggested relocation would have moved the port’s commercial heart closer to industrial areas, with a projected 50,000 additional jobs created over ten years of construction.

Crucially, the HPC proposal expected to generate $2.5 billion dollars in profit, which would be managed by an independent public trust rather than the Lebanese government and current port authorities. Royal Haskoning and Khoury Consultants have not yet released any information about winning the contract for the masterplan nor their intentions for engaging civil society.

For its part the World Bank has promoted the fact that “The best thing about it [the port masterplan and law] is new governance and open and transparent procedures”[9]. At the time of publication however the World Bank had not detailed which civil society groups the masterplan intends to consult, nor how their perspectives and priorities would be included. When questioned by The Alternative, the World Bank released a statement claiming that “Any firm with the required qualifications and that do not [sic] have conflict of interest with the assignment was allowed to bid, including Hamburg Port Consulting”.

Cart Before the Horse

It has become apparent that the World Bank and Lebanese government perceive the redevelopment process differently. Just one week after the law reform and masterplan project was formally announced, Minister of Public Works and Transport Ali Hamie awarded CMA-CGM – a French multinational with Lebanese ties – a ten-year contract to operate the Beirut Port’s container terminal. In entering this agreement, the government did not wait either to complete the precinct’s new master plan or draft and implement the proposed legislative reforms.[10],[11] The World Bank was not involved in the tendering process for redeveloping the container terminal.

USAID, which conducted an extensive feasibility study for the redevelopment of Lebanon’s ports, has warned against taking major decisions without embedding a sound governance structure first. “The (governance) transition could take 1-1.5 years, provided there is strong political commitment,” the USAID study concluded.

In an especially eyebrow-raising detail, the CMA CGM contract is issued and managed by a central target of the proposed regulatory reforms: the Temporary Committee for Management and Investment of the Port of Beirut (GEBP in French). The GEBP has run the Beirut Port since 1993, despite being constituted as a mere a stop-gap administrative body until a formal port authority could be established. The GEPB’s opaque management and lack of financial transparency have raised serious questions over the ensuing decades.220408_Beirut-Port-Triangle-Policy-FEATURE

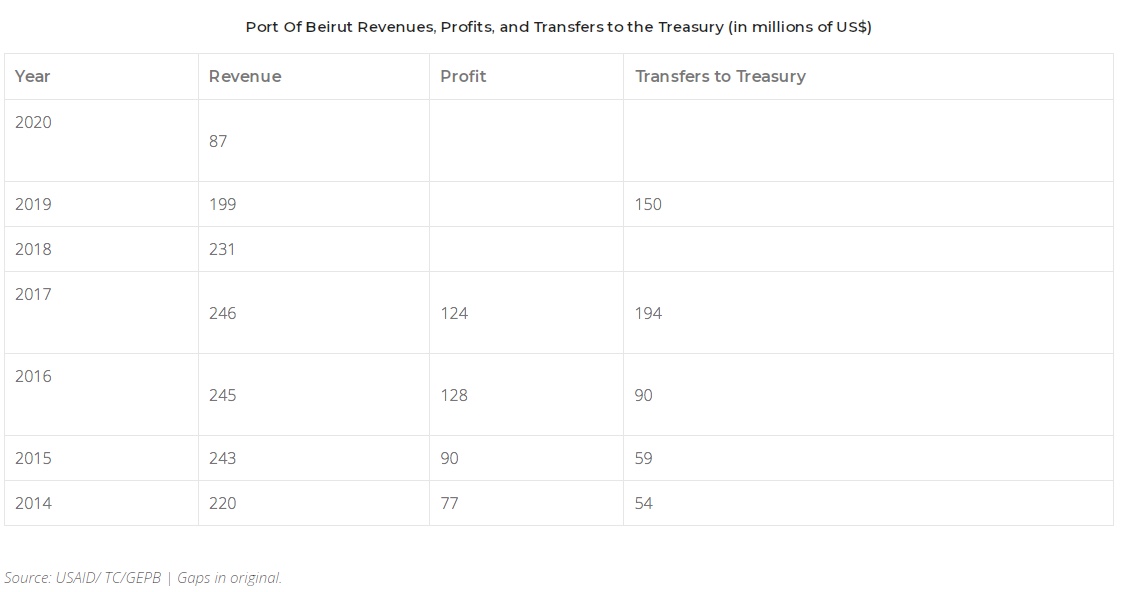

The USAID assessment details how the GEPB does not submit its accounts to the Ministry of Finance for scrutiny and has included loans from international development banks among its revenues. Instead of a set rate of profit transfer to the government, the GEBP passes on unpredictable and unexplained portions of its profits.[12]