Real Estate Alchemy: Turning Foreign Cash into Lebanese Concrete

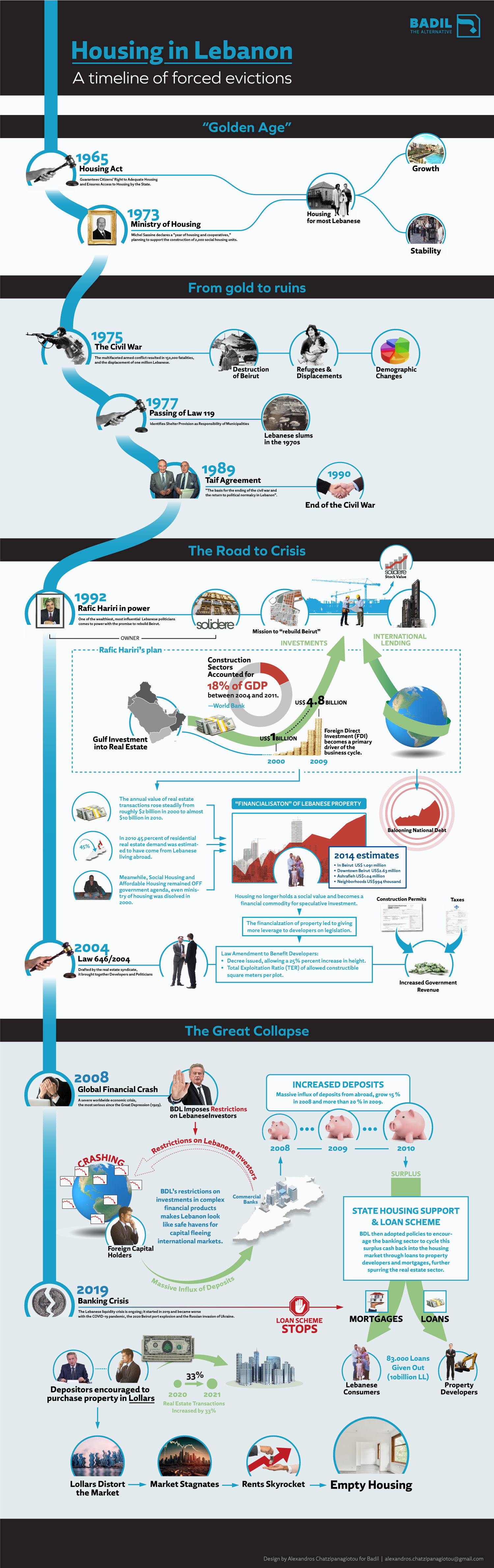

Spiking oil prices in the early 2000s generated surplus capital for many Gulf Arab investors and expatriot Lebanese living in the region, which the Lebanese government then sought to intice into the country’s real estate sector. As documented by Marieke Krijnen, whose master’s and PhD research focused on Lebanese housing issues, this included government deregulation, tax incentives, increasing the allowable builtup area of developments, as well as facilitating foreign property ownership and foreign company operations in Lebanon.[14] The result was that between 2000 and 2009, annual FDI rapidly increased from almost US$1 billion to US$4.8 billion, with the majority of this going into real estate.[15] The resulting property boom led to real estate and construction sectors accounting for almost 18 percent of gross domestic product between 2004 and 2011, according to the World Bank, while productive sectors, such as manufacturing and agriculture, were starved for investment.

While the 2007-2008 Global Finanial Crisis ravaged financial institutions around the globe, those in Lebanon actually benefited from the crisis. Banque du Liban (BDL), Lebanon’s central bank, had restricted the country’s commercial banks from investing in the complex financial products from which the crisis emerged, protecting Lebanese banks from the fallout and leading them to be seen as safe havens for capital fleeing distressed international markets. The Lebanese banking sector consequently saw a massive influx of deposits, which grew 15 percent in 2008 and more than 20 percent in 2009. BDL then adopted policies to encourage the banking sector to cycle this surplus cash back into the housing market through loans to property developers and mortgages, according to Krijnen, further spurring the real estate sector.

The annual value of real estate transactions rose steadily from roughly $2 billion in 2000 to almost $10 billion in 2010, and in the latter year as much as 45 percent of residential real estate demand was estimated to have come from Lebanese living abroad. In the decade that followed, however, foreign investment in the country’s real estate sector steadily shrank, with much of this attributed to declining oil prices and the 2011 Syrian uprising-turned-armed conflict.[16] BDL then pivoted to targeting domestic demand to prop up the real estate market, offering commercial banks incentives loans to the resident Lebanese population, such as subsidizing mortgage interest rates for domestic borrowers, as well as continuing to offer developers favorable loan conditions. These messures helped the value of annual real estate transactions stay within a range between US$8 billion and US$9 billion from 2012 to 2018, according to Bank Audi – with the exception of 2017, when sales reached almost US$10 billion.

“We used housing as a foreign investment in the country and we have sold housing to as many well-off people as we can,” Mona Fawaz, professor of urban studies and co-founder of the Beirut Urban Lab at the American University of Beirut, told The Alternative. “It has created a situation in which everyday people started competing with banks, and investors, for access to a house.”

How Housing ‘Financialization’ Built a City of Ghost Homes

During the post civil war growth period, social housing and the creation of affordable housing stock remained low on the government agenda. This was typified by the dissolution of the Ministry of Housing in 2000, which came as a real estate boom was gaining momentum. Amid the cacophony of drilling, bulldozers, cranes and clearing, concern grew over the elite clientele who would ultimately benefit from these developments and the inability of the average Lebanese to affordable a home.

In Feburary 2014, the Lebanese real estate advisory agency Ramco reported that the average cost of an apartment in Beirut stood at US$1.09 million. In the area of Downtown where Solidere-led construction took place the average price was around US$2.63 million. In the Achrafieh area it was US$1.04 million, and for the neighbourhoods in west Beirut assessed the average price stood at US$994,000.[17]

In August the same year, a joint UNHCR and UN-Habitat report on housing, land and property issues in Lebanon noted that this was “far beyond the means of the vast majority of the population” considering that the monthly minimum wage was the equivalent of US$350.[18] At the time it was also estimated that there were some 200,000 apartments sitting unsold in Lebanon.

The growing disparity between home prices and what the general population can afford is a consequence of what urban planners and experts have described as the ‘financialisation’ of Lebanese property. This refers to the shift from housing being regarded as holding social value (ie. providing homes for families) to it being seen as financial commodity for speculative investment.[19] A 2017 United Nations report noted that the financialisation of housing was an emerging trend globally, and deemed it a major barrier for access to adequate housing around the world.

Various experts have argued that the financialisation of Lebanese land and housing, facilitated by unfair land policy, has been the primary factor driving inequity in Lebanon’s housing market and damage to Beirut’s urban environment. Abir Saksouk, an urbanist and architect with the Housing Monitor research platform, said that Lebanon’s building and planning laws do not include any criteria related to social, environmental, or economic factors.

“It is all about how we can build higher,” she told The Alternative. “Land was transformed into a commodity instead of offering a social value. This took shape in multiple laws and policies that were produced since the early nineties that encouraged and facilitated real estate investment and foreign investment in land.”

Private developers exersized a great deal of influence on the regulatory framework given that “an overwhelming majority of the Lebanese politico-economic elite who enact laws also invest heavily in real-estate,” according to Hisham Ashkar, an architect and urban planner who has studied the gentrification process in Beirut. Indeed, a recent report by the Gherbal Initiative showed that, of the 66 Lebanese politicians they assessed, they held an average of 27 real estate investments each.

The overlap between property ownership and government policy was particularly apparent in the drafting and passing of the Construction Law of 2004, which set the stage for Beirut to emerge as the chaotic concrete jungle it is today. The law, for example, allowed the height of high-rises (defined as 50 meters tall) to increase by 25 percent. The height increase was a win for developers as apartment prices generally increase by at least $100 per square meter with each successive floor.[20] Another amendment was made to increase the total exploitation ratio, meaning how much a developer is allowed to construct on any given plot of land.[21] While this increases developers’ potential return on investment, the cost to the general public is the loss of green spaces and open areas.

The onset of Lebanon’s financial crisis in 2019 further distorted the housing market, according to Fawaz. She pointed at how investing in real estate was considered a viable alternative for depositors seeking to move their funds out of commercial banks.

The rush-to-buy saw a 33.3 percent increase in the number of real estate transactions from December 2020 to December 2021, with the value of those transactions at $15.55 billion, an 8 percent increase from the previous year, according to Blominvest Bank. But the growth was short-lived; in the first seven months of 2022, sales fell by 15 percent year-on-year, according to a Bank Audi report. The report noted that the drop in business reflected the real estate sector’s shift from accepting checks to requiring physcial cash payments in dollars.

Sales have since remained stagnated and overall property prices in the city have declined from pre-2019 levels. A study by Ramco Real Estate Advisors and L’Orient-Le Jour looking at the sales prices in Beirut neighbourhoods shows a weakened market. One luxury apartment in Furn el Hayek in Achrafieh was sold for $1.1 million in 2021, or $1,850 per square meter, considerably lower than the typical asking price for luxury apartments in Lebanon of over $3,000 per square meter.[22]

Public Housing Support, Private Developers Still Benefiting

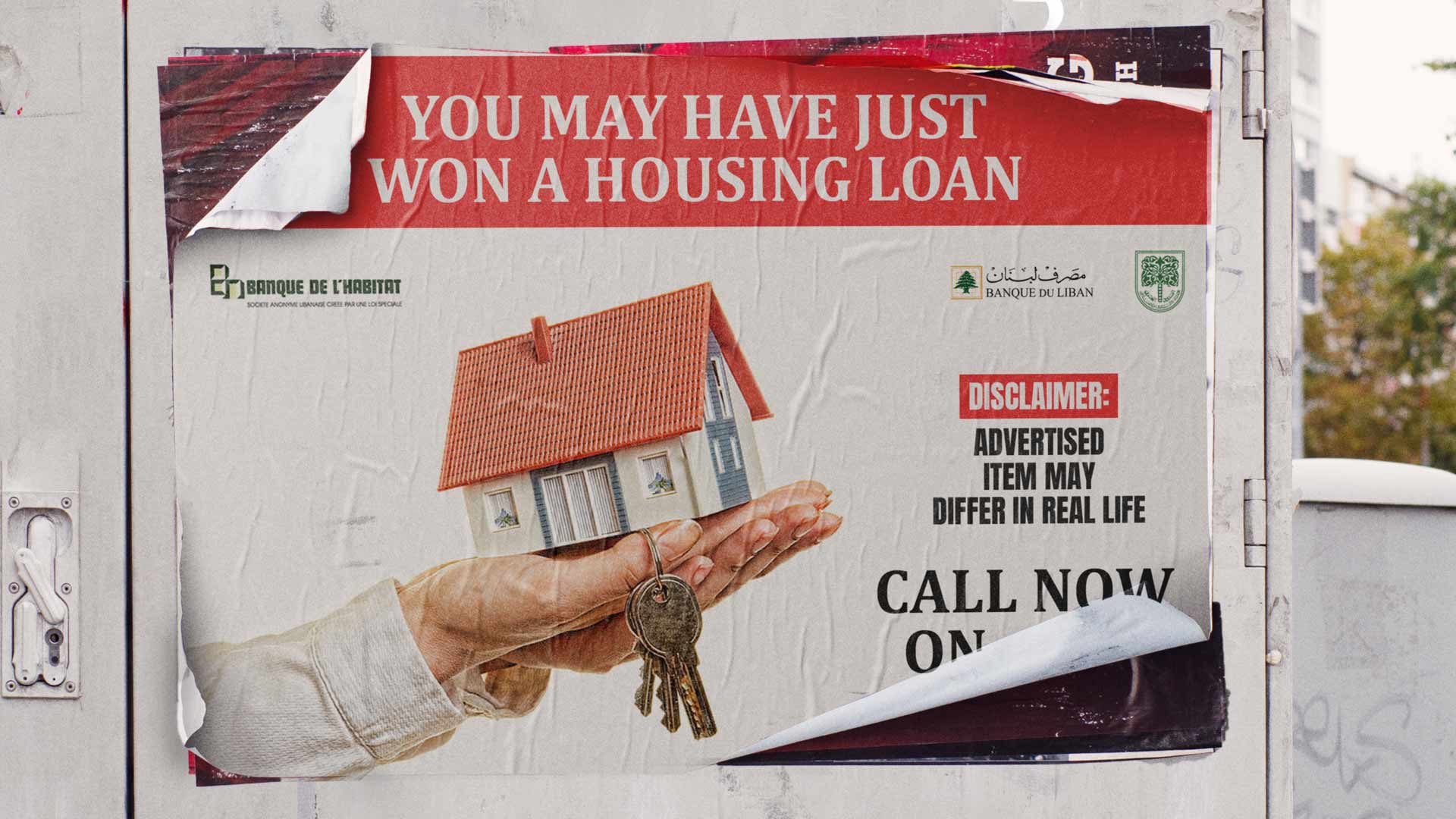

As real estate attracted investment and bank capital during the boom years, the state’s interest in adhering to its constitutional promise of a citizen’s right to adequate housing was limited. In this regard, the government’s primary initiative has been the public housing loans scheme under the guise of the Public Corporation for Housing (PCH). Established in 1996 within the Ministry of Social Affairs, the PCH introduced state sponsored housing loans to help facilitate home ownership among middle income groups. The PCH, together with the BDL, the Ministry of Finance, and 30 Lebanese commerical banks devised the mortgage-based homeownership scheme.

From 2000 to 2018, the PCH processed 83,000 loans worth 10 trillion Lebanese pounds (roughly US$6.6 billion at the pre-crisis exchange rate) for applicants who met the necessary criteria, according to the organization’s General Director and Chairman Roni Lahoud.

“We were giving loans for people to build their own apartments or properties, to renovate the existing properties, or to extend existing properties, and the biggest portion of loan taking was to purchase and own an apartment,” he said. Lahoud added that the PCH handled more than 60 percent of all government subsidised housing loans, with military and security forces’ housing plans making up the remainder.[23]

The effectiveness of the loan policy is, however, under debate. Abir Zaatari, a housing researcher with the Beirut Urban Lab, noted that the central bank “focused on supporting real estate demand through financing the residential sector.”

She says this involved increasing the cap on PCH housing loans in 2008 from $53,000 to $120,000, and again in 2011 to $180,000, as a response to the increasing gap between the purchasing power of homebuyers and housing prices.[24] The loan subsidy values made available to consumers thus chased, and thereby contributed to, the soaring property valuations during the real estate boom, according to Zaatari.[25]

The loan policy’s overwhelming focus on the middle class also meant acute working class housing challenges remained unaddressed. Entirely absent from government policy were state-run, socially affordable housing endeavours. The financial means for various levels of government to pursue such was not a major obstacle: the Beirut municipality, for instance, experienced a windfall of revenue from construction associated taxes and permits during the real estate boom years. By the end of 2015, the city had accumulated a US$800 million war chest, a large proportion of which was gained from construction permit fees and municipal taxes, according to both Fatha, the council member, and Jihad Bikai, head of engineering at the municipality.[26] Nour, of Solidere, estimated that between 70 to 80 percent of this revenue came from construction permits alone. Social housing projects, however, hardly crossed the radar of municipal officials, according to Bikai, who says that most of the city’s initiatives are “in the interest of real estate developers and everything else comes later.”

Old Rent, New Rent

Data on the proportion of Beirutis that rent rather than own their home is scant. The United Nations Development Program (UNDP), citing rental contracts registared with the municipality, asserted in 2008 that there was roughly an even split between the two, with half the city’s households owning their dwelling and the other half renting.[27] Importantly, however, these numbers exclude informal rental arrangements. City of Tenants, a recent study by Beirut Urban Lab assessing living conditions, found that more than half of the households surveyed had only verbal rental agreements. It’s thus safe to assume that most Beirut residents are renters.

Perhaps the signature move by the Hariri government to support affordable housing, which arguably helped more Lebanese keep a roof over their head than any other government decision, is what became known as the ‘old rent’ law. Enacted in July 1992, it froze, in perpetuity, the value of all rental agreements signed previously, while rental agreements signed after the enactment faced no such price controls. Over the years, with inflation, the old rent law has allowed many families to stay in homes while paying well below market value for their rents. According to Blominvest Bank, in 2014 there were 125,000 households in Beirut still benefiting from the 1992 law.[28] While the depreciation in the rent values over the years ostencibly benefited tenants, it also resulted in the poor building upkeep and maintenance, given that landlord revenues on their properties continued to fall in real terms.

In 2014, Parliament voted to end the protections provided by the old rent law. The new law stipulated that old rents would be allowed to rise gradually over the course of nine years to a “fair lease price”, to be set at 5 percent of the property’s estimated market value. The legislation also called for government housing subsidies to be provided to low income earners to help cover the rent increases. The onset of the financial crisis and the collapse of the lira has thrown implementation of the new rent law into disarray, however, particularly in regard to how to calculate property values and new rent prices when most old contracts were negotiated in lira.

The City of Tenants survey has consequently found that the proportion of tenants paying rent in US dollars has been increasing. In 2020, 30-35 percent of survey respondents said they were paying in US dollars; by 2022, 75 percent reported paying rent in American cash, according to the Beirut Urban Lab.

The vast majority of Lebanese still earn wages in Lebanese lira, however, meaning the trend towards rent dollarization is effectively a dramatic rent hike for many. Saksouk, from the Housing Monitor, told The Alternative that in some cases landlords are violating both rental laws and tenant contracts by demanding rent in dollars.

“Even though the rent law states that the rent contract is three years and during these three years the landlord can’t evict, can’t raise the rent and change the value of the rent, this is happening all the time,” she said. “In terms of practises there are massive violations to the rent law [happening].”

The City of Tenants survey noted a surge in the number of renters depending on support from aid groups and family to continue to afford the cost of rent and utilities. Saksouk, meanwhile, said that the Housing Monitor is receiving increased calls for help from individuals faced with eviction. She said a large proportion of those calling are non-Lebanese, such as Syrian refugees and migrant workers. She noted that there was a variation between these cases with rent paid in dollars or Lebanese pounds.

“Today you’re at the supermarket and everything is in dollars; this is what is going to happen to housing incrementally,” Saksouk said. “Evictions and homelessness are going to be on the rise, so we definitely need an emergency plan for housing, for shelter. This is crucial because it is definitely going towards dollarization.”

In 2018, following the end of the PCH’s housing load scheme, Lahoud said the organization began working on a “housing rescue plan.” He says that although the plan was signed off by the Ministry of Social Affairs, it has remained in limbo of the ongoing political impasse, waiting to be approved by the Council of Ministers. According to Lahoud, the plan seeks to address the fragmentation of housing matters by unifying the “process of decision making to avoid overlapping responsibilities and conflicts of power between the different institutions of housing.”

While he was reluctant to reveal specific details, he said the plan includes amendments to the rent law to define standards of adequate housing, “because at the moment you can rent anything even without windows.” He said it also suggests determining a rent cap according to the apartment’s condition and location, and introducing a rent-to-buy scheme.

The PCH’s plan also seeks to address what Lahoud described as “slum areas” of Beirut which he said referred to houses built illegally mainly during the war; however, it remains unclear as to how they were going to be addressed.

Looking Ahead

The challenges facing affordable housing and the urban environment in Lebanon have been decades in the making, with the ongoing economic crisis only exacerbating the hardship for many. However, the crisis has also radically disrupted the prevailing status quo and in this erosion of past precedencies there is also an opportunity to plot a different path forward. Many experts and policy makers who spoke with The Alternative for this article said now is the time to reassess, plan and propose new housing and urban management policies in Lebanon. While addressing the massive inequities and imbalances in the housing market is a long-term challenge, the recommendations compiled below from expert opinion represent realistic entry points to begin making tangible and meaningful reforms.

Implement a vacancy tax. One low-hanging fruit for a housing reform takes the shape of a vacancy tax. In the case of Beirut, where there is a high number of vacant properties across the city – reportedly up to 50 percent in some affluent areas[29] – such a tax can be a starting point to increase supply in the rental market and in turn drop prices. A vacancy tax usually takes the form of an annual fee as a percentage of the property’s value and is a method increasingly used in cities globally to disincentivize the myopic, financialized approach to housing whereby an apartment is solely seen as an asset. Instead, it incentivizes property owners to recognize that the fundamental role of housing is to provide homes for the population, and that they hold a responsibility in this regard. Vacant property taxes, through increasing available rental units, also provide an opportunity to reinvigorate neighborhood life and reduce vehicle traffic by allowing more people to live closer to where they work or study. Importantly, however, until the value of the Lebanese lira is stabilized within a reasonable range, it may be challenging to assess the official value of properties for tax calculation purposes.

Implement Land Value Capture (LVC) strategies in urban planning. LVC is an approach to urban planning to help governments pursue urban infrastructure projects – such as street lights, sidewalks, green spaces or public transport – in a consistent, predictable and financially sustainable manner. A pillar of the LVC approach is ring fencing government revenues from taxes, fees and permits associated with real estate and development activities for spending on urban infrastructure projects. The value of the taxes and fees business and individuals pay thereby becomes physically apparent in the built environment around them, which in examples from other cities has led to improved tax compliance and increasing levels of trust between state and citizens.[30]

Develop an urban policy strategy to address abandoned and dilapidated buildings. The creation of an urban policy strategy to understand the root causes of why properties are abandoned can help address the city’s dilapidated buildings and offer ways to improve long-term living conditions. It would also provide approaches to regenerating housing stock in formal and informal neighborhoods (ie. housing built without permits, often during the civil war). Among the initiatives that could be built upon in this regard is a program in the works by the Beirut Urban Lab to address the high number of abandoned and dilapidated buildings in the city. It involves identifying buildings which have been abandoned for decades and since lived in by poor families. These buildings not only lower the overall livability of neighborhoods, but often have an accumulation of unpaid taxes where the municipality has neglected to intervene. [31] The Lab, in collaboration with UN agencies and NGOs, has plans to work with the municipality to upgrade these properties, pay off the debts and transform them into affordable housing stock.

Formalize and regulate the rental market. The rental market must be formalized to include the informal rental sector. Steps should also be taken to define and regulate standards for adequate housing and caps for rental price increases.

Require new developments to allocate a certain portion of their new apartments for affordable housing. Imposing regulations on new developments that mandates them to allocate a certain number of apartments for price caps, according to pre-set socioeconomic criteria of the customer, is a direct means to increasing social housing provision.

[1] Nadine Bekdache, Evicting Soverignty: Lebanon’s Housing Tenants From Citizens to Obstacles, The Arab Studies Journal, Fall 2015

[2] Housing Monitor, The legitimacy of dwellings or the right to live in them?: Housing projects and their informal transformations in Sidon and Tripoli, Tala Aladdin, Rayan Aladdin, Maya Saba Ayoun

[3] Interview with Mohamed Said Fatha, engineer and Beirut Council Member, May 30 2023

[4] The Politics of Sectarianism in Postwar Lebanon, Bassel F. Salloukh, Pluto Press, 2015

[5] Idib.

[6] Bassel F Salloukh, The Politics of Sectarianism in Postwar Lebanon, PlutoPress, 2015

[7] Jinan S. al-Habbal, The Politics of Sectarianism in Postwar Lebanon, PlutoPress 2015, page 45; Joseph Daher, Lebanon: How the Post War’s Political Economy Led to the Current Economic and Social Crisis, European University Institute, January 2022

[9] Bruno Marot, The Financialization of Property and the Housing Market in Lebanon, Legal Agenda, https://english.legal-agenda.com/the-financialization-of-property-and-the-housing-market-in-lebanon/

[10] Joseph Daher, Lebanon: How the Post War’s Political Economy Led to the Current Economic and Social Crisis, European University Institute, January 2022

[11] Kubursi, Atif A. “RECONSTRUCTING THE ECONOMY OF LEBANON.” Arab Studies Quarterly 21, no. 1 (1999): 69–95. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41858277.

[12] Atif A. Kubursi, Reconstructing the Economy of Lebanon, Arab Studies Quarterly, Winter 1999

[13] Joseph Daher

[14] Marieke Krijnen, The Spatial Fix in Lebanon: Remittances, Petrodollars, and the Global Financial Crisis

[15] Idib.

[16] Bank Audi, Lebanon Real Estate Sector, July 2020

[17] Al Akhbar English, Beirut for the Rich Only: An Average of $1m for a Residential Apartment, February 14, 2014, https://ramcolb.com/pdf/Al-AkhbarFebruary14[3].pdf

[18] HOUSING, LAND & PROPERTY ISSUES IN LEBANON IMPLICATIONS OF THE SYRIAN REFUGEE CRISIS August 2014, UNHCR and UN HABITAT

[19] https://www.ohchr.org/en/special-procedures/sr-housing/financialization-housing#:~:text=Housing%20and%20real%20estate%20markets,rather%20than%20a%20social%20good.

[20] Hisham Ashkar, Lebanon 2004 Construction Law: Inside the Parliamentary Debates, October 2014, https://civilsociety-centre.org/paper/lebanon-2004-construction-law-inside-parliamentary-debates#footnote12_beao3il

[21] Hisham Ashkar, Lebanon 2004 Construction Law: Inside the Parliamentary Debates, October 2014, https://civilsociety-centre.org/paper/lebanon-2004-construction-law-inside-parliamentary-debates#footnote12_beao3il

[22] Guillaume Boudisseau, Apartment prices in Beirut in 2021: How much is an apartment in Achrafieh?, L‘Orient Le-Jour, 5 October 2021 https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1276893/apartment-prices-in-beirut-in-2021-how-much-is-an-apartment-in-achrafieh.html

[23] Home Loans Exacerbate Inequality, Housing Monitor https://housingmonitor.org/en/content/home-loans-exacerbate-inequality

[24] Abir Zaatari, Housing Production in Uneven Urban Quarters: Two Case Studies From Beirut (Lebanon) Aicha Bakkar and Tallet El Khayyat, American University of Beirut, October 2019

[25] Abir Zaatari, Housing Production in Uneven Urban Quarters: Two Case Studies From Beirut (Lebanon) Aicha Bakkar and Tallet El Khayyat, American University of Beirut, October 2019

[26] Interview with Mohamed Said Fatha, engineer and city council member, 29 May 2023, Interveiw with Jihad Bikai, head of engineering Beirut Municipality, 10 April 2023

[27] https://publicworksstudio.com/en/migrant-workers-and-refugees-are-facing-a-dilemma/, Interview with Maya Saba Aoun, Public Works Studio, March 2023

[28] https://blog.blominvestbank.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/2014-05-The-End-of-Rent-Control-in-Lebanon-Impact-Analysis.pdf

[29] https://beiruturbanlab.com/en/Details/612

[30] https://www.lincolninst.edu/publications/articles/value-capture#:~:text=As%20a%20policy%20approach%20currently,government%20actions%2C%20such%20as%20rezoning.

[31] Interview with Abir Zaatari from Beirut Urban Lab