Brick by Brick

The responsibility for ensuring a building’s safety is shared between municipalities, building owners, and the Order of Architects and Engineers (OAE). The OAE is tasked with approving building permits and ensuring all regulations are met.

According to OAE member Imad Amer it is the responsibility of the engineer to ensure the structural integrity of a building. However, many structurally unsound buildings were built informally or before the OAE began regulating the sector in 1951.

“The municipality has a mandate to ensure property owners protect public safety, and if they don’t, it has the mandate to take over and charge them,” said Fawaz. “Yet, it never does. Landlords too are mandated to maintain buildings for safety repairs, but many don’t.”

According to Zouheiry, implementing safety regulations is nearly impossible for property owners, as many residents still benefit from Lebanon’s old rent law and pay rent at pre-civil war prices.

“Some renters pay around 100,000 Lebanese Pounds (LBP) per year,” she said, “Today, this amounts to about three dollars. That is why the owners cannot afford to make the needed repairs.”

According to Maroun Helou, President of the Syndicate of Contractors and Public Works, the safety issue is arguably worse in Lebanon’s villages.

“I can tell you that in Beirut this work [implementing safety regulations] is almost always taken seriously by the authorities, but in the villages, where there is less professionalism, [adverse] incidents can happen.”

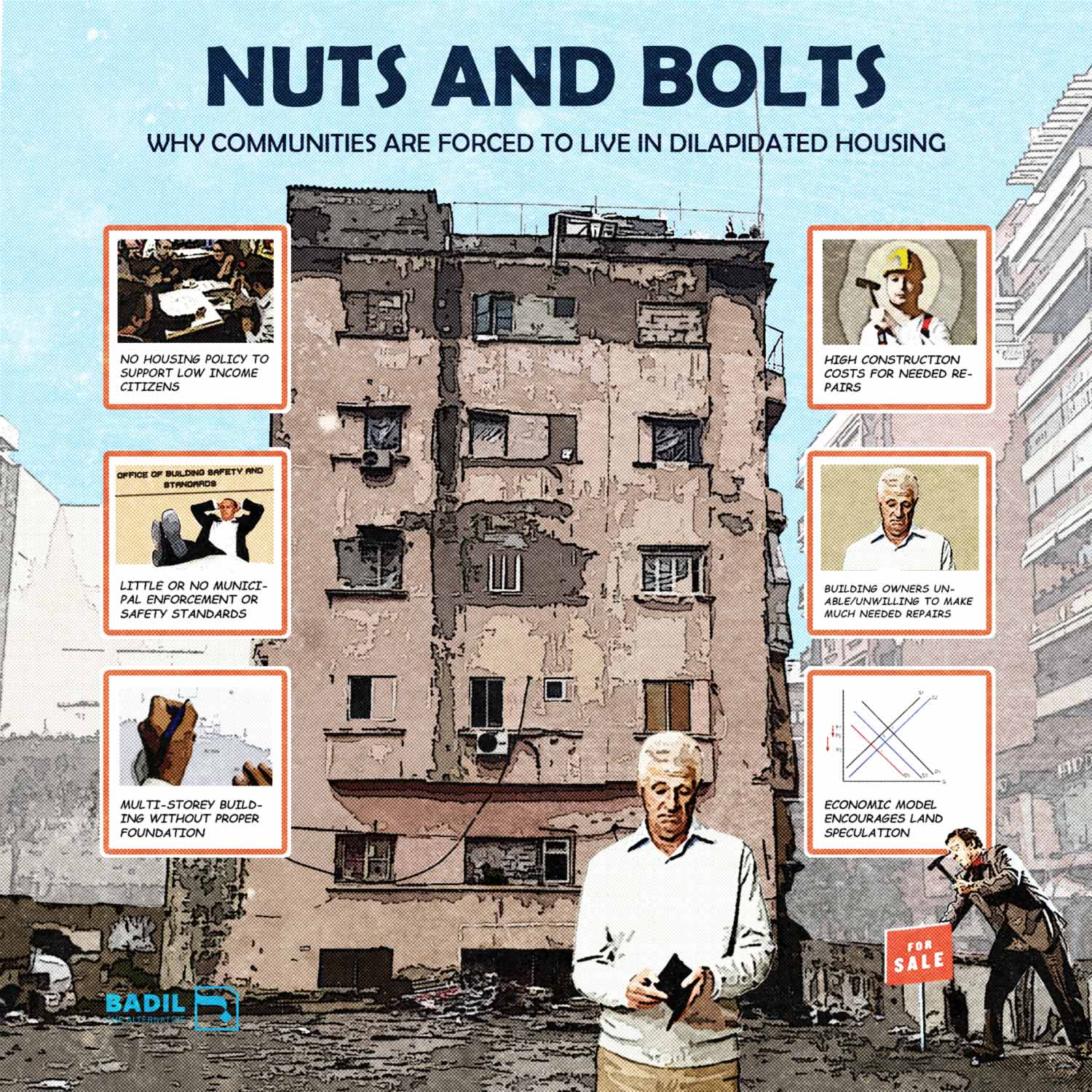

Low-income communities are often shoehorned into existing properties. When expanding, they are forced to build up by adding floors on top, while lacking proper permits and the required foundational support. Usually, this occurs in informal urban settlements housing low-income communities, although it can affect middle-income neighborhoods too.

Fawaz gave the infamous Mar Michael building in Beirut, which collapsed following the Beirut Port explosion, as an example. The building had two additional floors built on top without proper foundational support.

Building Blocks of a Crisis

The cornerstone of Lebanon’s economic model following the end of the Civil War was to attract foreign capital in what was later deemed a financial house of cards. This included the government enacting laws that favored transnational developers over the city’s residents.

According to Fawaz the marginalization of low- and middle-income communities is a result of an “economic model that encourages speculation,” which sees people buy and hold onto real estate in the hope the price will increase without any regard for social values.

When lower-income residents are priced out of safe housing, they will have to find residence elsewhere. Given that most of them work in urban areas, hampered by a lack of affordable public transport, they are forced to seek refuge in dilapidated urban housing.

Meanwhile, Beirut’s apartment vacancy rate stood at a whopping 23% in 2019, which jumped up to almost 50% for high-end apartments. [2] Economists generally consider 5% a healthy vacancy rate for the rental housing market.[3]

“We force people to live at risk in the name of private property,” said Fawaz.

Vacant urban properties can have a negative effect on the economy, which is why most cities around the world tax vacant buildings. True to Lebanese exceptionalism, vacant properties in Lebanon are exempt from taxes. Introducing such taxes would encourage Lebanon’s property owners to lower rents, resulting in more affordable and safer housing options.

Beirut inhabitants are all too familiar with the sight of empty high-rises and unfinished development projects juxtaposed against unsafe and overcrowded apartment blocks. The reconstruction of the Beirut downtown area by the Lebanese company Solidere has been burned into Lebanon’s collective memory. The once bustling city center is now a ghost town of empty or unfinished real estate projects and parking lots.

Rock the Foundations

Meanwhile, a far more alarming and destructive threat rumbles underground. Lebanon sits on an active plate boundary known as the Levant Fault System. Building safety standards have been updated to include earthquake resistance.

“However, nobody enforces it, or almost nobody,” said Fawaz. “This is tragic, because we are on a severe fault.” In the event of an earthquake, the number of casualties would no doubt be devastating.

“I don’t see a solution [for Lebanon’s housing crisis] before a serious transformation of Lebanon’s political system is set in place,” said Fawaz. “The decisions made to encourage speculation were taken by those actors in government, who also work outside of it to either finance or develop land.”

[1] UNICEF, 2018, “El-Qobbeh Neighborhood Profile,” online at: https://www.unicef.org/lebanon/media/631/file/Lebanon-report-3-qobbeh.pdf

[2] Beirut Urban Lab, “A City For Sale,” online at: https://www.beiruturbanlab.com/en/Details/612/beirut%E2%80%99s-residential-fabric

[3] Mike Gedal, Ioan Voicu, The Furman Center For Real Estate & Urban Policy, 2005, “Recent Trends in the Availability & Affordability of Housing in New York City,” online at: https://furmancenter.org/files/sotc/SOC2005_RecentTrends_000.pdf