The ‘qualitative shift’ has seen far more senior and influential figures voicing support for Palestine. As an example, Englert point to, “people within the civil service, such as state employees, are starting to break rank, and some even resigning.”

Among other examples are US Senator Bernie Sanders, who has questioned the unconditional aid provided to Israel, and US Senator Elizabeth Warren who also declared “no more blank checks for Netanyahu.” Former director at the State Department Josh Paul resigned over arms deliveries to the Jewish state, while Craig Mokhiber, the director of the New York office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCR), resigned. In Spain, the Barcelona Municipality suspended its ties with Israel over Israel’s humans rights violations, as Social Rights Minister Ione Belarra called on the European Union to sanction Israel. Most recently, the Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez declared on March 9, 2024, that he will propose that the Spanish parliament recognise a Palestinian state. In Ireland, Prime Minister Leo Varadkar also declared that his government would be in favour of recognising the state of Palestine. In the Netherlands, a Dutch court ruled against the government by ordering it to halt the deliveries of F-35 fighter jet parts used by the Israeli army. In France, the Foreign Ministry expressed frustrations with the French President’s handling of the war.

As a result, the Palestine cause, often been seen as fringe issue in western politics, has been mainstreamed, thereby creating a spectrum of support that transcends traditional ideological boundaries.

Rising BDS momentum and the backlash

Established in 2005, the Boycott, Divest, and Sanction Movement has aimed to apply economic and political pressure on Israel to readdress its persecution and apartheid policies towards Palestinians. The boycott aspect involves consumers actively avoiding products and services associated with Israel, divestment actions mean pushing institutions and companies to withdraw their investments from Israel, and sanction efforts are meant to lobby governments to impose economic and political restrictions.

Prior to October 7, 2023, the BDS movement had claimed many successes. Namely, positing that its targeted campaigns led to multinational companies such as Veolia, Orange, G4S, General Mills, and CRH exiting the Israeli market, and HSBC bank and the Norwegian Sovereign Wealth Fund divesting from Elbit, Israel’s largest arms manufacturer. The companies and institutions in question, however, regularly cite business or regulatory concerns as prompting their decisions. Gaging how much BDS campaigns weighed on their boardroom decisions is therefore unclear. Even when NSWF publicly stated that Elbit’s role in securing illegal Israeli settlements in the West Bank prompted its divestment, the announcement made no mention of the BDS movement.

As the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) continue to militarily pulverise the Gaza Strip in the months since Operation Al Aqsa Flood, further momentum has built to disassociate from Israel both commercially and financially. For example, various global pension funds have divested from their Israeli investments, while the Norwegian Pension Fund’s sale of nearly half a billion dollars’ worth of Israeli government bonds contributed, according to activists, to Moody’s downgrading Israel’s credit rating for the first time in the country’s history in February. Again, it is difficult to discern how much these moves were based on the sound business calculation that a country at war is unsafe for investment, or the ethical and reputational risks of being seen as financing Israel’s slaughter of Gazans and apartheid policies in the West Bank. Or, perhaps, a convenient combination of both.

In other instances, the motivation has been clear. For example, in February 2024 the student government at the University of California Davis voted to prohibit any of its $20 million budget from being spent on “companies complicit in the occupation and genocide”, citing corporations such as McDonald’s, Sabra, Starbucks, Airbnb, Disney and Chevron.

Starbucks, in particular, became a symbol of the boycott movement after the company’s board sued the Starbucks Workers United union, encompassing some 360 stores and 9,000 employees, for an October 9 “Solidarity with Palestine” post on X (formerly Twitter). McDonald’s became a boycott target after McDonald’s Israel announced that it provided thousands of free meals to the IDF. While analysts argue that the boycott campaign against Starbucks has only had a negligible impact, Al-Shaya Group, the Starbucks franchise owner in the Middle East and North Africa region, reportedly plans to cut 4 percent of its workforce across the region “as a result of the continually challenging trading conditions over the last six months”. At the same time, McDonalds reported “meaningful” negative impact on its business in the Middle East, though the region constitutes just 5 percent of the company’s global business.

A growing number of labour unions globally have also taken steps to show solidarity with Palestine. This included dock workers in countries like the US, Spain, Belgium, Italy, and Greece, refusing to handle military equipment bound for Israel. Last month in India, workers across 11 ports refused to handle all cargo ships transporting weapons to Israel following a motion from one of the country’s major trade unions. Meanwhile, in higher education, a substantial number of academics have advocated for their institutions to cut off relations with Israeli academic entities due to the escalating conflict in Gaza.

International sanctions against the Israeli state still seem politically unpalatable for most western governments. However, some American and European lawmakers have attempted to temporarily stave off public criticism by sanctioning extremist Israeli settlers in the West Bank.

Building the networks of resistance amid backlash

Despite growing support for the aims of the BDS movement, none has proven effective in dissuading Israel from its military assault on Gaza, which the International Court of Justice has said “plausibly” constitutes genocide. Neither has the increased pro-Palestinian solidarity prompted Israel’s staunchest ally, the US, from continuing to replenish the Israeli campaign with weapons as well as repeatedly vetoing United Nations Security Council resolutions calling for a ceasefire.

Western policymakers have, for years, sought to directly counter the BDS movement. For instance, nearly 300 bills have been introduced in various US states since 2014 to try to limit actions related to BDS. As of March 2024, 23 percent of these bills were passed across 38 states. The UK legislators have similarly sought to quelch BDS activism.

This legal stance, coupled with public campaigns branding BDS supporters as anti-Semitic, fosters an antagonistic atmosphere, deterring potential allies and casting doubt on the movement’s intentions and legitimacy, thereby compromising its effectiveness and outreach. Students and academics demonstrating for Palestine have also frequently been targets for retaliation across the US and Europe.

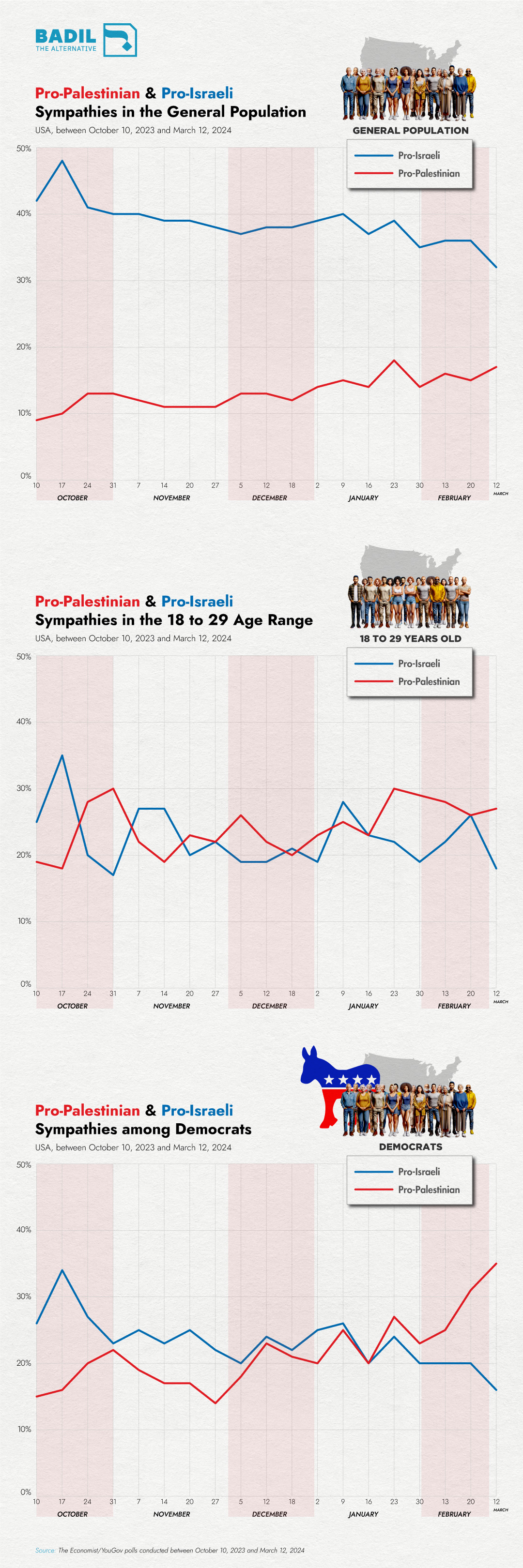

It is thus apparent that despite the recent growth in pro-Palestine support, it remains overshadowed by a more pervasive pro-Israeli sentiment. This disparity manifests in public opinion, media representation, and political discourse, curtailing the efficacy of pro-Palestinian advocacy in these areas.

The current popular mobilisation has, however, provided an opportunity for people to organise locally, nationally, and internationally. As Englert points out, “activists have been establishing robust organisational structures, such as setting up committees and networks, which not only foster a solid foundation for advocacy, but also provide a constructive outlet for people to express their concerns and actively engage in the movement.”