EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

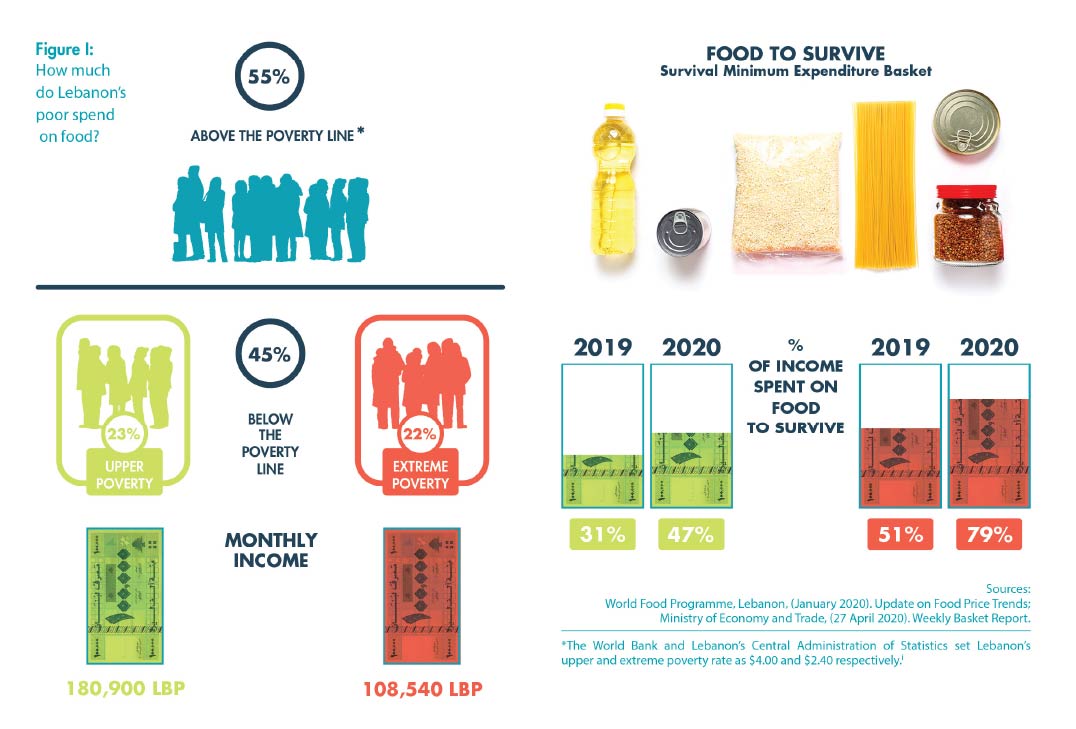

The Lebanese people are trapped in a nightmare. On top of the deadly, mysterious COVID-19 pandemic, they are grappling with an economic collapse so complete that, based on government estimates, it will take over 20 years to fix. Now virus and recession have joined forces to send food prices skyrocketing and household incomes nosediving. The result: almost half of the population struggles to put the most basic foods on their tables.

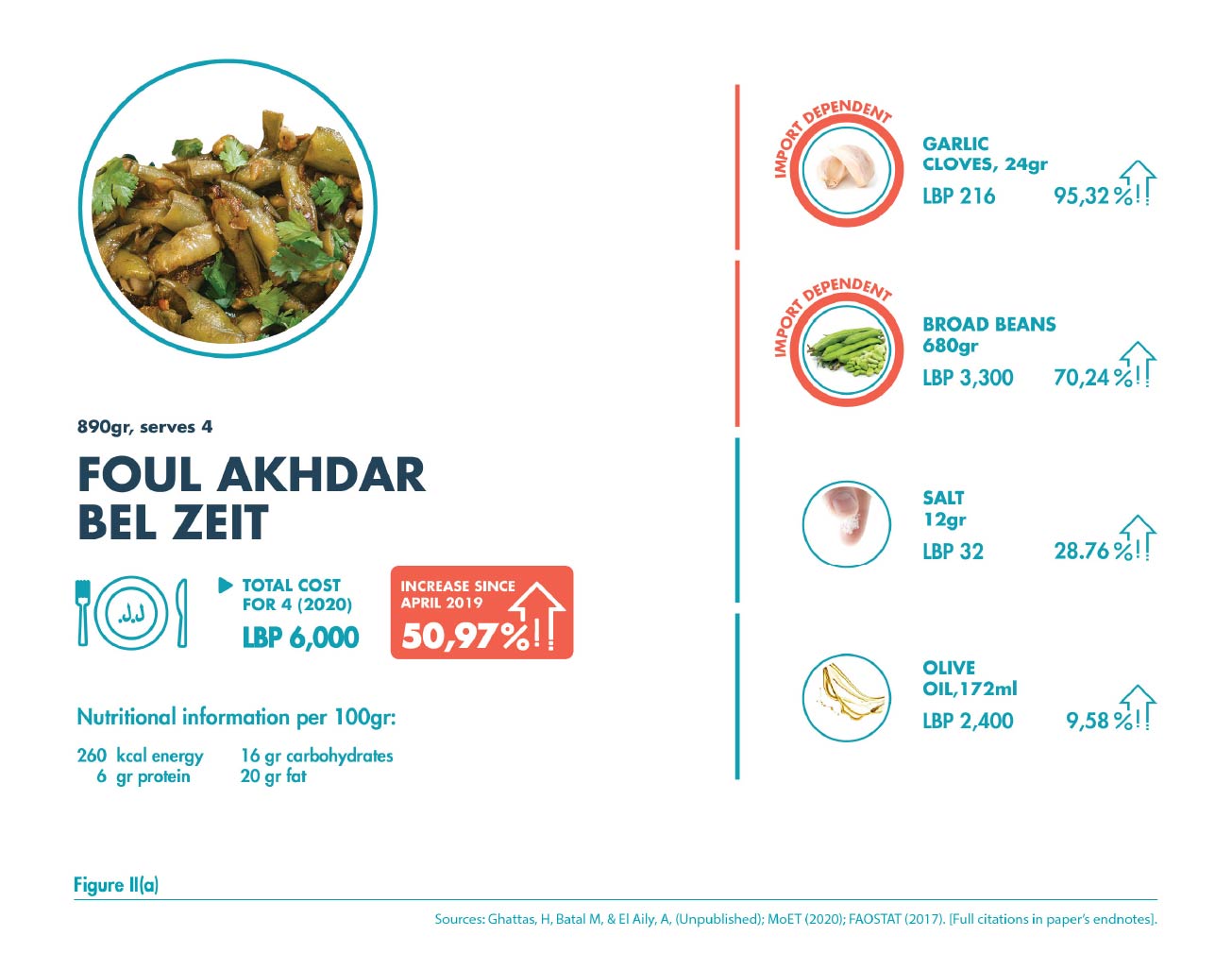

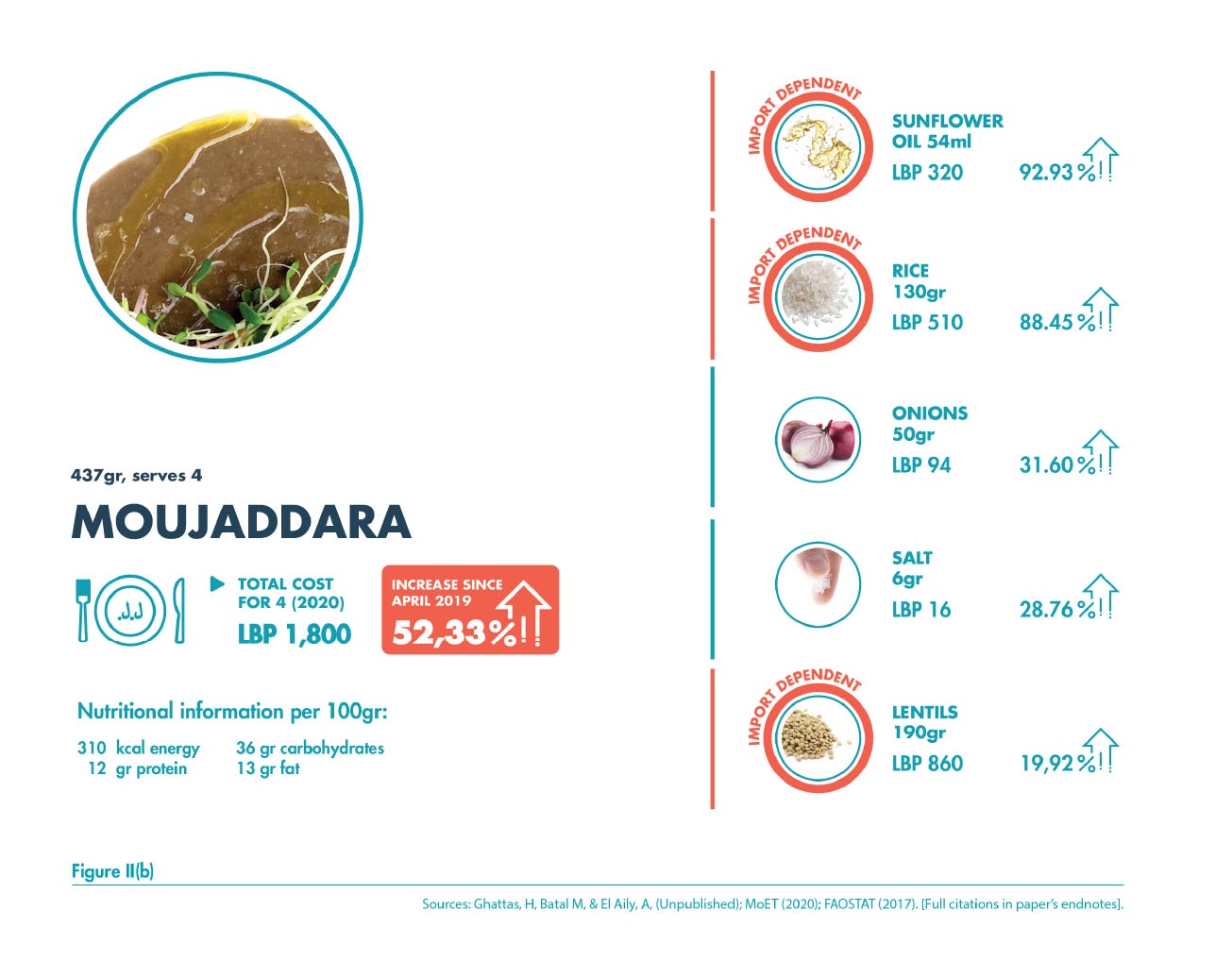

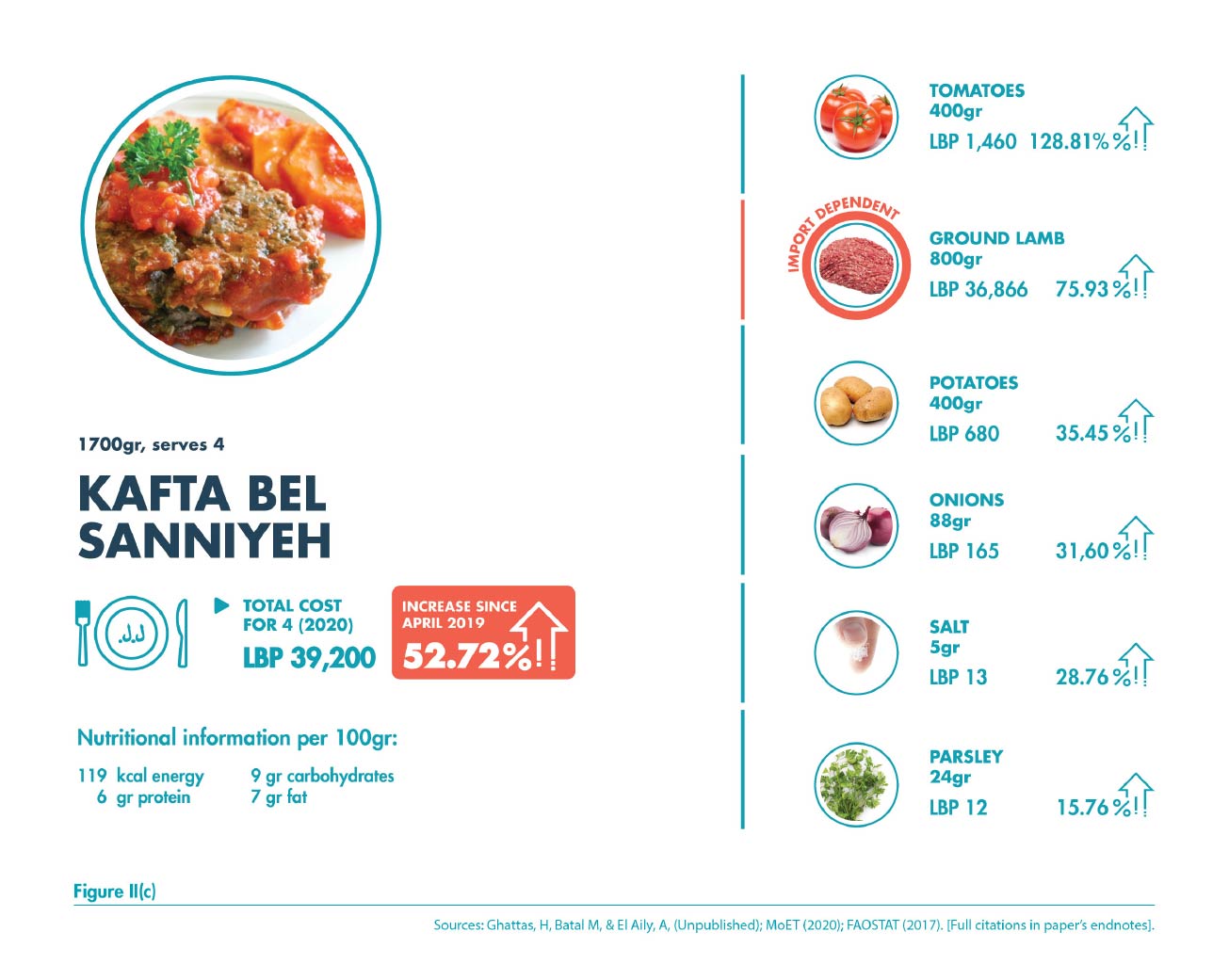

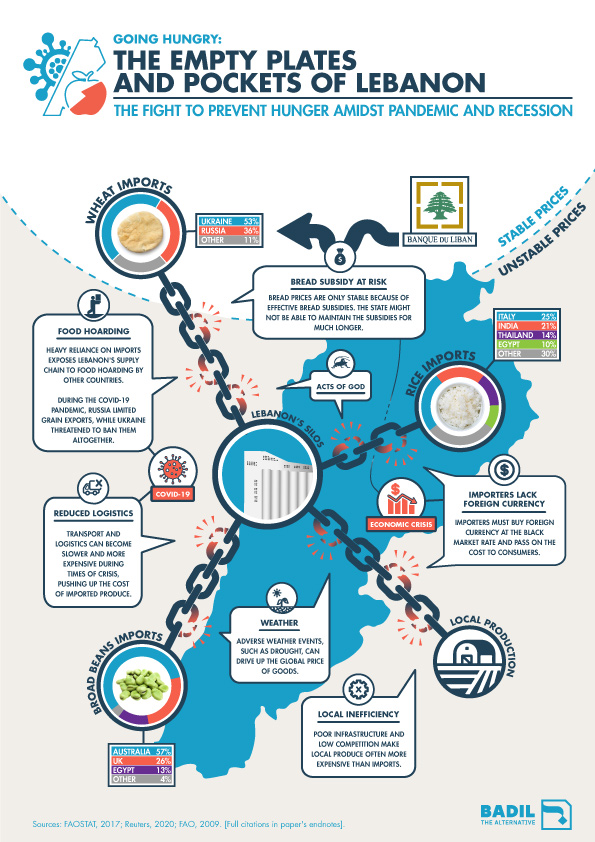

In truth, the looming spectre of widespread starvation is not a bad dream, but a reality deeply rooted in political decisions made over decades. Once the breadbasket of the Roman Empire, Lebanese agriculture now contributes just 3% of annual economic growth, despite providing jobs for one quarter of the national labour force. Farmers contend with woeful infrastructure, directly resulting from a chronic lack of state investment, and have weak bargaining positions against wholesalers and retailers. This makes Lebanese-made food neither particularly abundant nor cheap, with imported foods often being more affordable.

Lebanon’s food supply chain will always rely on foreign products to a significant extent, given the country’s limited land and water resources. However, the ongoing currency shortage has made imports much more expensive, exposing the critical limitations of overwhelming import dependency—a disappointing legacy for a region which pioneered domesticated wheat some 9,000 years ago1. Now international politics is also threatening Lebanon’s supply lines, as key food producing countries consider imposing export bans and quotas amid COVID-19-related panic.

To make matters worse, powerful importers and traders can drive up prices on both local and imported foods through cartel behaviour, capitalising on Lebanon’s non-existent or toothless consumer protection and competition laws. With the deck stacked so shamelessly against consumers, it is no wonder that low-income households across Lebanon were already food insecure, long before pandemic and recession struck.

Lebanon’s unacceptable lack of food security calls for immediate action. In the short term, the government must crack down on price-gouging and expand social safety net programmes through cooperation with the Banque du Liban (BDL) and international aid organisations. Simultaneously, a comprehensive strategy for long-term food and nutrition security is desperately needed. This plan should improve infrastructure to boost local production, whilst weeding out non-productive wholesalers and corrupt captains of industry in favour of the small-scale farmers that add true value.

Lebanon can only navigate these perilous times by—quite literally—going back to its roots. With some state support, farmers could easily boost food sovereignty by growing more nutritious staples such as beans, lentils, and chickpeas, which have long been native to the region. The current economic order has driven Lebanese and refugees alike to the brink of starvation. The new Lebanon needs to put the people first, which starts with guaranteeing basic, universal food and nutrition security. Nothing less will allow this generation to uphold the old Lebanese adage that “nobody ever dies from hunger.”

INTRODUCTION

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, hot on the heels of a catastrophic economic collapse, has exposed the brittle foundations of Lebanon’s food and nutrition security.2 The two crises have joined forces to send food prices skyrocketing and household incomes plummeting, imperiling access to the most basic levels for sustenance for increasingly destitute families.

The Lebanese people have not had the luxury of taking food and nutrition security for granted in modern history. Their nation occupies an arable yet relatively tiny portion of a water-scarce region, which exposes local agriculture to external shocks. The 1918-20 Spanish Influenza outbreak, the most recent pandemic on the scale of COVID-19, came at the end of the devastating Great Famine of Mount Lebanon: 200,000 people died of starvation as wartime politics cut off international supply chains, while locusts decimated Lebanese crops. The threat of hunger, augmented by disease, bore down on all.3

Instead of locusts, today’s Lebanese can blame the colossal extent of their food insecurity on a new breed of insatiable pestilence: the elite capture which brought the economy to its knees through decades of theft, venality, and financial misconduct (See Triangle’s November 2019 paper, “Extend and Pretend”). The ongoing recession has directly inflated prices for virtually all foods, but especially in relation to imports, which can only be purchased with increasingly scarce foreign currency. In a country like Lebanon, which relies overwhelmingly on foreign-made products, these price trends have had disastrous consequences.

With food and nutrition insecurity now looming over the nation, the besieged Diab government has started to heed public demands for immediate action. The Ministry of Economy and Trade has proposed new laws to crackdown on illegal profiteering on food prices, while it also explores options for temporary subsidies on essential foods. Separately, a leaked emergency plan emerged from the cash-strapped Ministry of Agriculture, setting out a quickfire agenda for improving Lebanon’s food and nutrition security by boosting domestic production.4 And perhaps most significantly, the government released its ambitious plan for financial recovery, aimed at arresting the inflation that has crippled food access across the country.5

History suggests that more steps, more reforms, and more investment will need to occur without delay. Just over a decade ago, Lebanon endured the 2007/08 global food price shock, which crippled food and nutrition security across West Asia and North Africa. Mass public anger erupted in the Arab Spring protests that swept the region two years on, as demonstrators decried their governments’ failure to ward off widespread hunger.6 Lebanese elites should recall these events with alarm, not least because food prices rose by 18.2% in 20087—a relative fraction of today’s ruinous 55% spike on basic produce.8

It is in this volatile context, now an existential crisis for rich and poor Lebanese alike, that COVID-19 has reared its lethal, microscopic head. This darkest of hours calls for full-scale cooperation—spanning all agencies, industries, and governorates—to make sure that everyone receives enough nutritious food.