Executive Summary

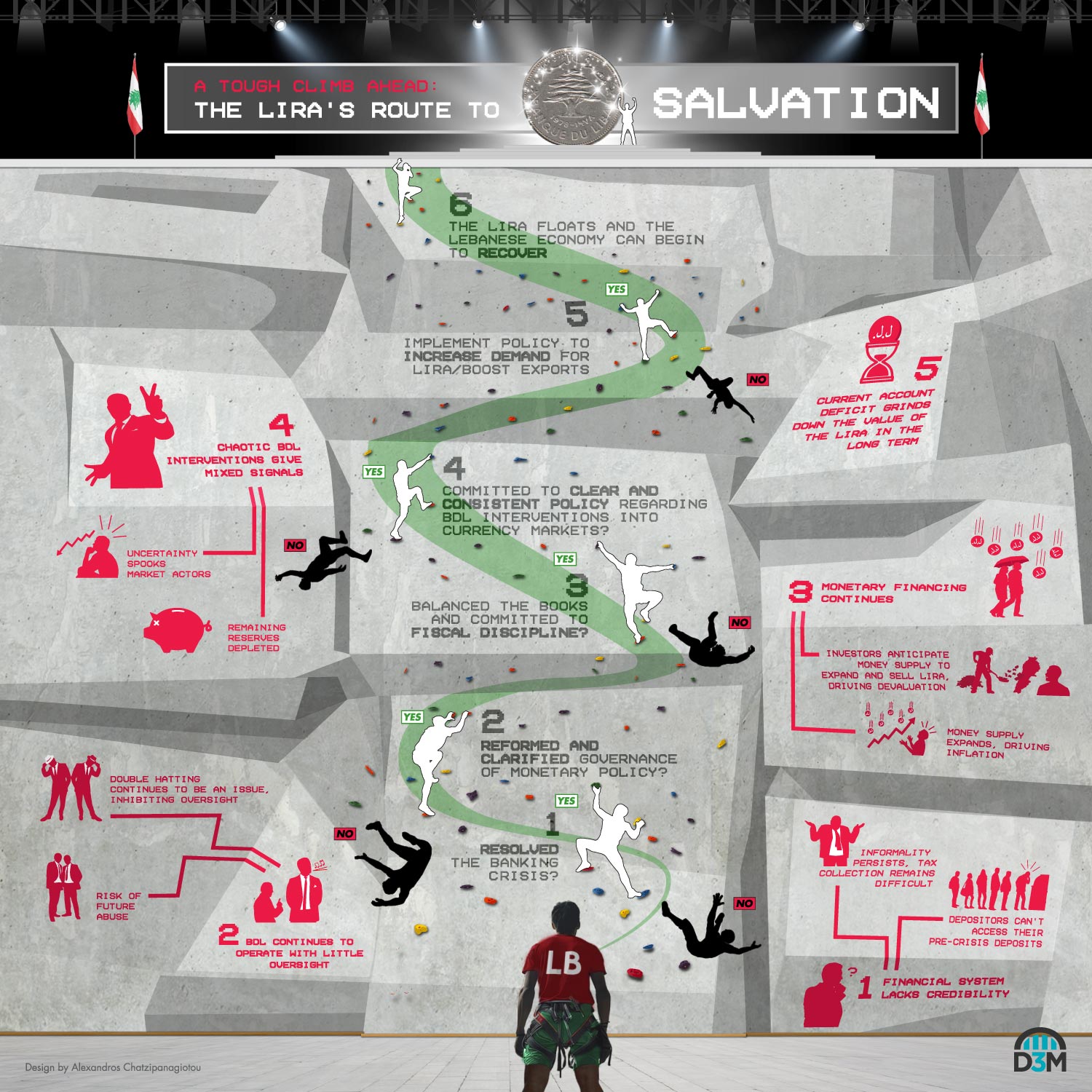

The government and central bank have deliberately failed to implement a coherent exchange rate regime in the wake of the financial crisis, instead opting to create endless, confusing exchange rates for different transactions. With the disgraced Riad Salameh leaving office at the end of July, his deputy Wassim Mansouri acceded to acting Governor. He and his colleagues presented a plan to float the lira by September along with a package of sorely needed reforms.

The plan, if implemented responsibly, will be a sharp departure from the government and central bank’s handling of the crisis thus far. Charged with resolving the implosion of the banking sector and cultivating a stable monetary environment, Salameh and the finance ministry instead created increasingly numerous exchange rates as the parallel market value of the lira has collapsed, creating arbitrage opportunities and market inefficiencies at every turn.

Meanwhile, the central bank printed ever more lira to finance the state which is unable to collect taxes or borrow money. As lira plunged further into the abyss, the difference in value between the lollar rate and market value of a dollar grew ever wider, forcing depositors to take larger and larger haircuts on their deposits imposed by illegal central bank circulars, but writing down the dollar-denominated liabilities of the banking sector.

For the lira to float without bringing more financial pain to those who have already suffered the most due to Salameh’s haphazard and harmful policies, the government and central bank must cease to print fresh lira to fund the government’s budget deficit, legislate a capital control law, and resolve the banking crisis – easier said than done.

Rebuilding the confidence of the markets by reforming the role and governance of the central bank and tightening fiscal policy is critical. To that end, both the 2023 and 2024 budgets need to be passed urgently, something that has proven to be difficult in Lebanon’s challenging governance environment.

The decision to do away with the Sayrafa platform should be welcomed as, like most components of Lebanese state, the platform quickly became another tool of state capture and daylight robbery, as the central bank subsidised favoured groups’ foreign exchange costs, generating $2.5 billion in arbitrage profits in the process. The creation of a transparent and efficient foreign exchange platform is key to floating the lira responsibly.

Salameh’s Out, Mansouri’s In

Riad Salameh, notorious central bank boss and darling of the political elite, ended his term at the end of July 2023. A period of uncertainty preceded his departure as the four central bank deputy governors threatening to resign if Salameh’s responsibilities were foisted upon them, giving life to speculation that he might be kept on.

Despite an initial unwillingness to step up to the plate, the first vice governor Wassim Mansouri has become acting central bank governor. Mansouri and his fellow vice governors have signalled their intentions to move to a flexible exchange, a departure from Salameh’s anti-reform stance, rate by September to help resolve Lebanon’s present economic quagmire.

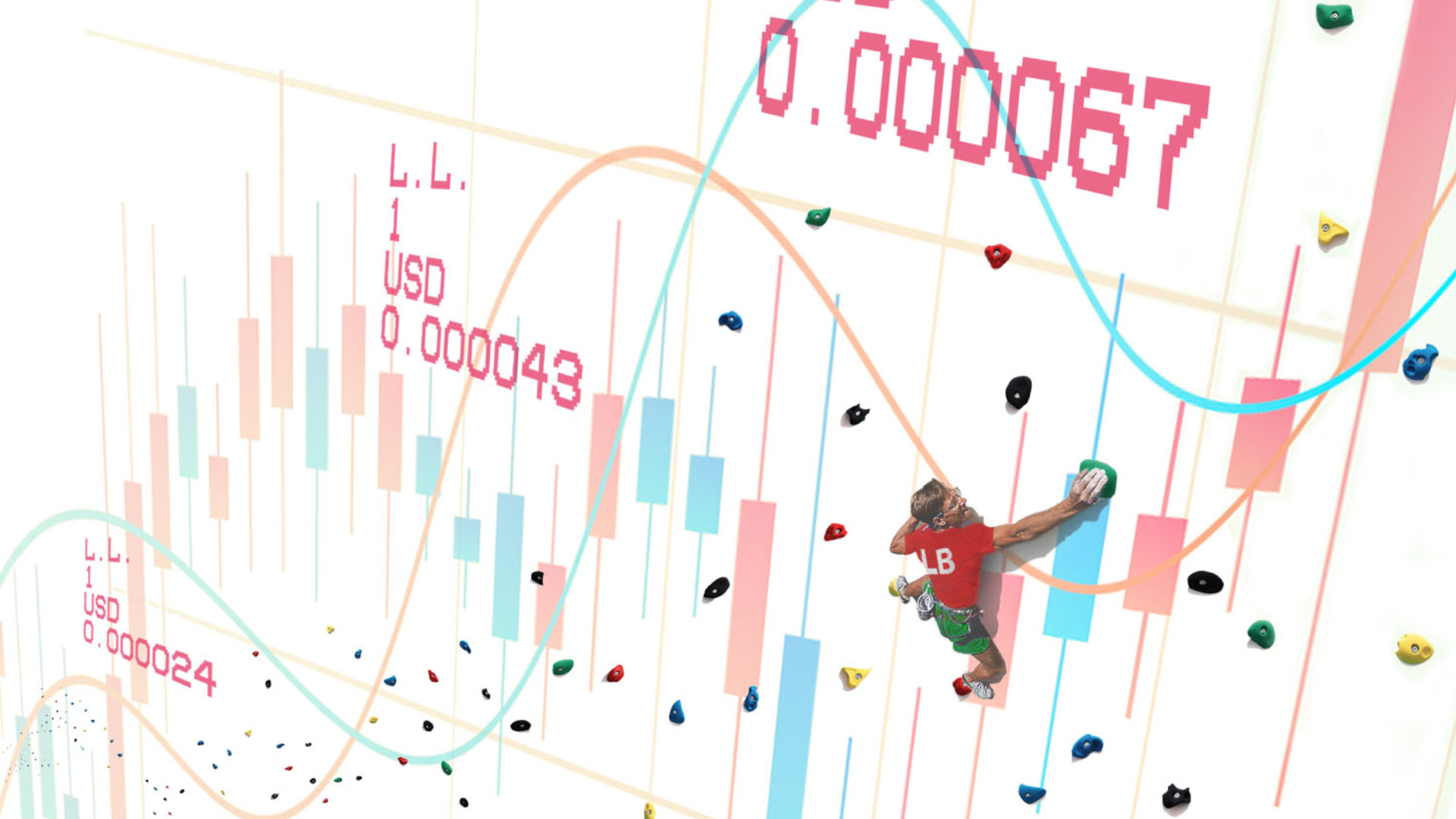

The mess Mansouri has inherited is formidable. The Lebanese financial crisis, caused by years of fiscal indiscipline, a skewed economic model dependent on inflows of foreign currency, illegal BDL circulars, and lack of confidence in the Lira have all lead in one way or another to a long and acute divergence between the official exchange rate and that of the parallel market.

Rather than reacting to the financial meltdown quickly, Salameh’s use of a fragmented exchange rate policy, characterised by different rates for different transactions, since 2019 created market distortions, spurred dollarization, and the decline of formal financial cycles. Central bank circulars forced an unfair distribution of losses from the collapse of the banking sector onto depositors that contributed to widespread poverty and skyrocketing inequality.

The plan presented by Mansouri and his fellow vice governors in late July 2023 proposed a managed float of the lira so that the exchange rate would reflect the “real” value of the currency. Over a six-month period, the deputies a series of reforms including major fiscal reforms, the issuance of laws to rebuild confidence in the currency, and the creation of a new foreign exchange platform.

The deputy governors stressed that the time is opportune to float the lira due to two factors: the country is awash with dollars thanks to tourist arrivals and a decrease in cash lira in circulation.

The plan, not yet approved by the government, marks a promising departure from Salameh’s ad hoc and centralized decision-making, however the appropriate reforms need to prevent the transition having disastrous consequences on the economy. If this were to occur, it would be the same social classes that have suffered from the government’s intentional mismanagement of the crisis that would suffer the most, especially in context of eroded social safety nets.

Imbalanced Books

Mansouri made it clear upon assuming his new responsibilities that the central bank must cease financing the government outside of legal frameworks. He warned that if the government continued to dip into the BdL’s coffers, that its hard currency reserves would eventually deplete, an unacceptable outcome given the need to resolve the banking crisis.

Although the proposed plan would allow the government to borrow up to $1.2 billion over 6 months, Mansouri stressed that the long-awaited 2023 state budget needed to legislate. Meant to have been passed in January, it needs to include adjustments to strengthen the fiscal regime, include progressive reform laws, such as a capital control law,x according to the new bank boss. This, however, requires the support of the political class, who have long used the state as a patronage vehicle.

The government’s imbalanced books have been a major driving factor behind the collapse of the lira’s value. Unable to issue new bonds, the Treasury has relied on the central bank printing new lira to fund its budget deficit. The M1 money supply rose from LL12.7 trillion in Oct 2019 to LL135 trillion in July 2023, an increase of 650%.

The inflated money supply has led to a long and severe decline in the lira’s value on the parallel market. This has eviscerated the public’s lira-denominated savings and salaries and further widened the gap between the cost of goods and the rate at which depositors can withdraw their trapped funds. This has served the elite by writing down commercial bank’s liabilities to depositors.

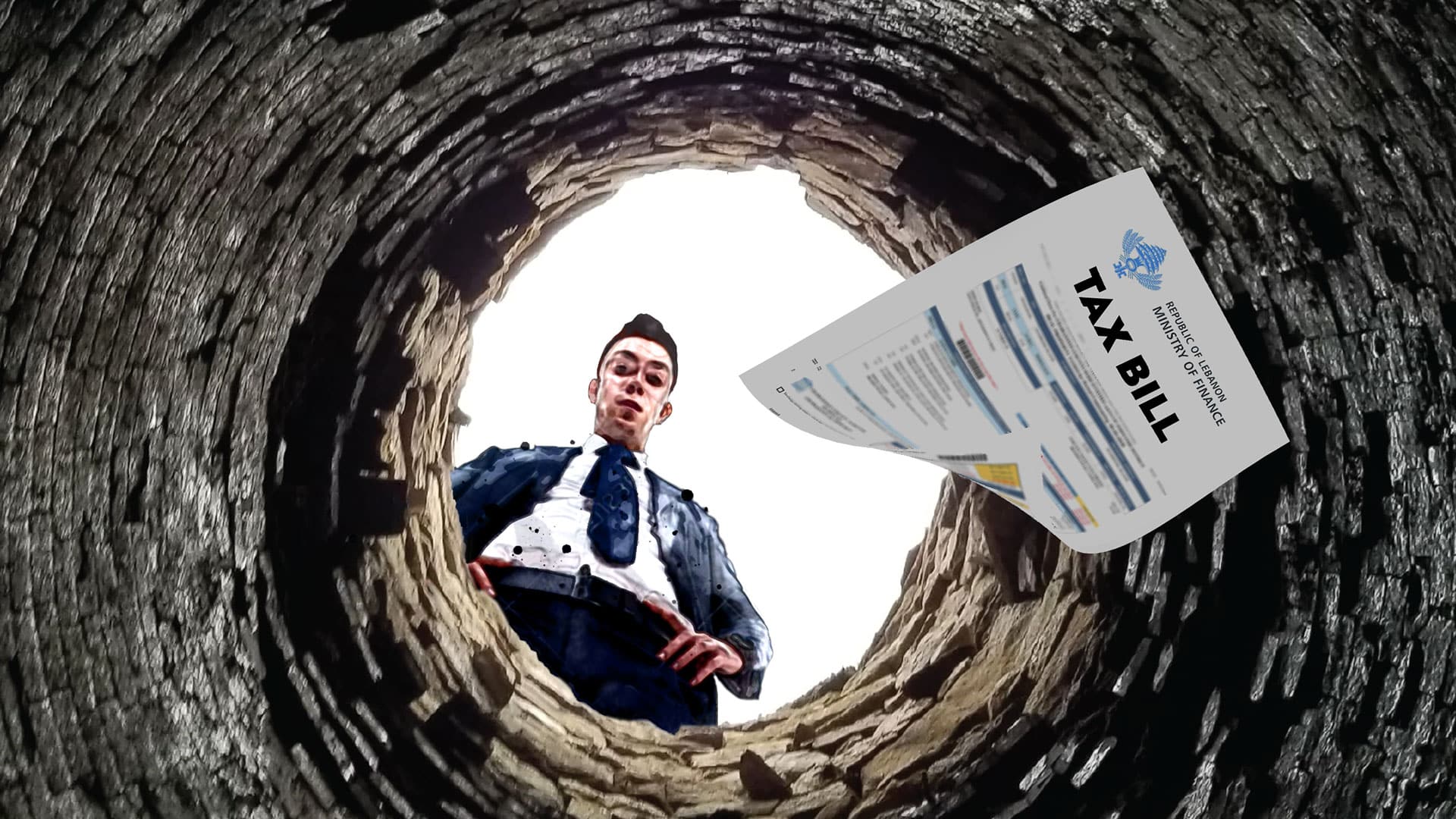

No Taxes? No Problem

The Lebanese government budget has for decades been characterized by overspending with little to show for it, which has led Lebanon to have the third worst debt-to-GDP ratio in the world at 171%. Unsurprisingly, debt servicing in recent years has been amongst the largest budget items, representing 32% in 2018, along with government salaries and subsidies for the public power producer – with the latter two woefully underperforming in spite of their cost.

Government tax revenues were equivalent to $7.81 billion before the crisis, or roughly 15-16% of GDP — a much lower proportion of tax revenue relative to economic activity than either Morocco or Tunisia, which are only marginally poorer. Following the crisis, tax revenue in Lebanon collapsed by 86%, equivalent to $1.13 billion.

At the same time, Lebanon’s tax policy continues to be characterised by a reliance on indirect taxes, weak revenues from progressive tax streams, and abundant loopholes for the rich to avoid taxation, placing the burden of taxation disproportionately on the middle and lower classes.

Collecting tax has only been made more difficult by the collapse of the banking sector. Its Byzantine rules and regulations drive an increasing proportion of transactions into cash, making tax evasion easier and more likely.