In February, Ali Hamie, Lebanon’s Minister of Public Works and Transport, achieved a milestone seemingly obligatory for all previous functionaries in his role. Brimming with confidence, Hamie announced the upcoming development of an ambitious plan to revive the country’s train network, which has lain derelict and unused since the civil war (1975-1990). Hamie’s plan aims to reduce the nation’s hours, wealth, and health currently lost to daily traffic congestion.

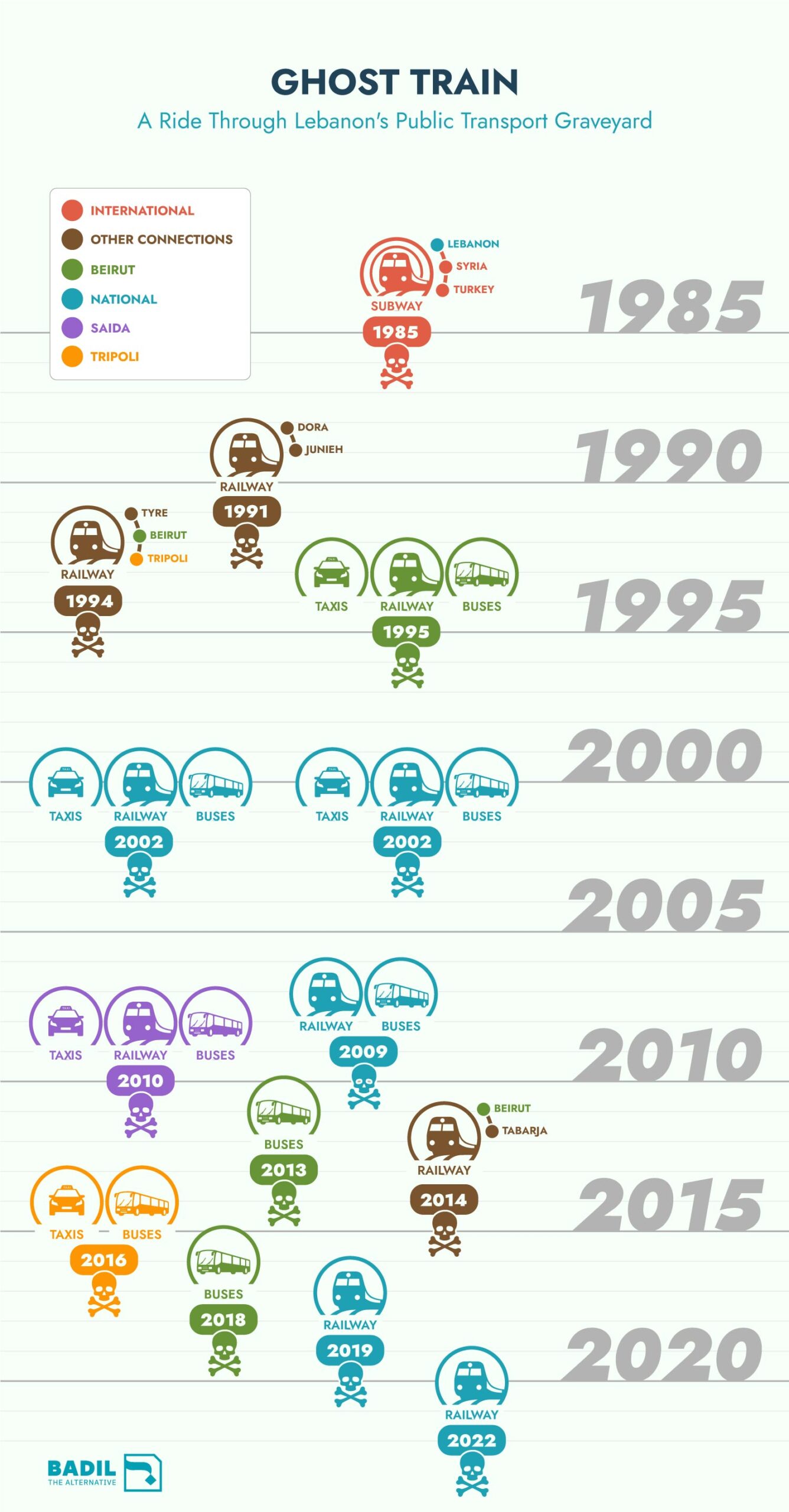

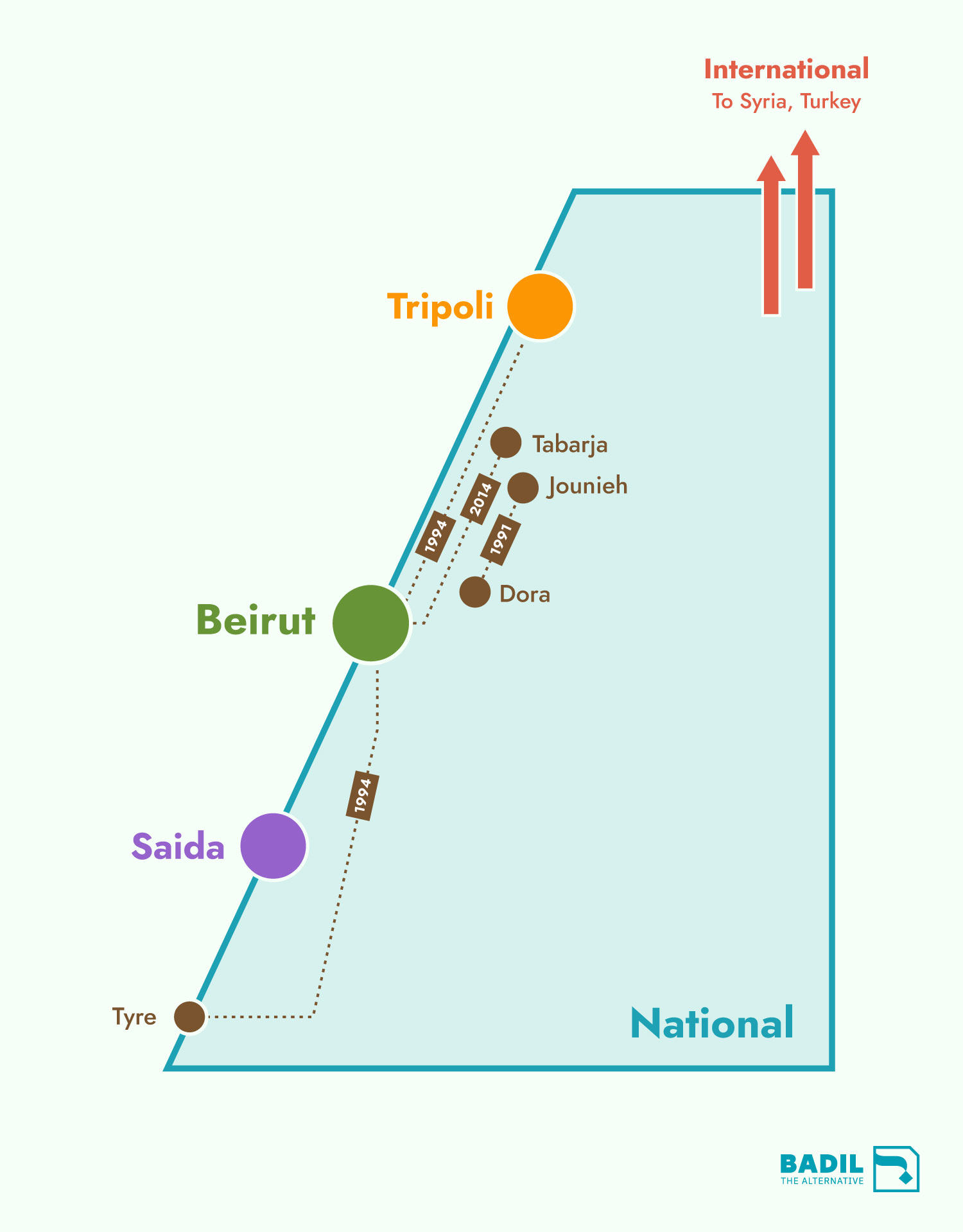

The trouble is that Lebanon has been here before – many times. Since 1985, the Lebanese government has made at least 13 such announcements, plans, proposals and / or studies about new public transport projects – an average of one every 2.4 years. These ranged from intra-city bus and taxi plans for Tripoli and Saida, to international subway and rail links to Syria, Turkey, and beyond. Ultimately, however, every single plan was aborted.

This time, the Spanish government has pledged to foot the bill for the national railway system study. In all likelihood, Spain’s taxpayers will fund yet another consultancy report, doomed to enter the graveyard of previous public transport plans for Lebanon.

According to Nabil Nakkash, an experienced researcher on Lebanese public transport, the obstacle has remained the same for decades – a lack of political will. “We have seen time and again for 30 years that the political class is not serious about public transport,” argued Nakkash. “We know what the problems are – and how to solve them – but it’s not in the politicians’ interest to do so.”

Indeed, Hamie’s train revitalization proposal illustrates how superfluous yet another study would be. Carlos Naffah, of Lebanese transport NGO Train/Train, was “shocked” by Hamie’s announcement. “Train/Train already presented a comprehensive master plan [for the train network] in 2019, for free,” said Naffah, referring to a proposal submitted to the Ministry of Public Works & Transport, as well as foreign embassies.

“Why would you reinvest in something that already exists?” Naffah mused. “The Spanish taxpayers will lose their money – it’s a scandal.” Train/Train’s proposal was also preceded by a 2018 World Bank-funded plan for a bus-centric public transport system for Greater Beirut.

The Ministry of Public Works & Transport did not respond to a request for comment.

Rather than redoing existing work, the ministry could use Spanish funds for advanced planning – such as prioritisation of projects set out in the 2019 Train/Train proposal – before moving to tendering and implementation. Such sensible policymaking would bring the Lebanese people closer to a functional train system.

Unfortunately, history suggests that the Lebanese government will scupper the upcoming train network plans with a familiar excuse: lack of funding. For almost every proposal launched since 1985, Lebanon’s leaders have blamed their failure to implement on not being able to afford modern public transport infrastructure. Amidst Lebanon’s unprecedented economic crisis, this justification for indolence looms larger than ever.

Aside from lacking in creativity, the government’s funding excuse ignores that the 2018 World Bank plan, included US$325 million in funding and reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of Lebanon’s transport predicament. While some of the more expensive proposals have been estimated to cost around US$6 billion, failing to act continues to impose an enormous bill on the Lebanese people. Private car usage alone – with 1.2 million registered private cars in 2015 – costs the country billions of dollars in oil imports, which most Lebanese can no longer afford. Indeed, the transport sector constitutes more than 40% of Lebanon’s unsustainable oil consumption levels.

On top of fuel spending, each year Lebanese commuters spend an average of 720 out of 4,380 productive hours on the road – costing an estimated US$3 billion per year in GDP. And annual health data indicates that around 2,700 people die from fossil-fuel attributed air pollution, to which cars are the main contributor.

These immense social problems will keep plaguing Lebanon until the country at last develops effective public transport. While Hamie’s promised train network would constitute an excellent start, history suggests that the Lebanese people should not hold their breath waiting for it.