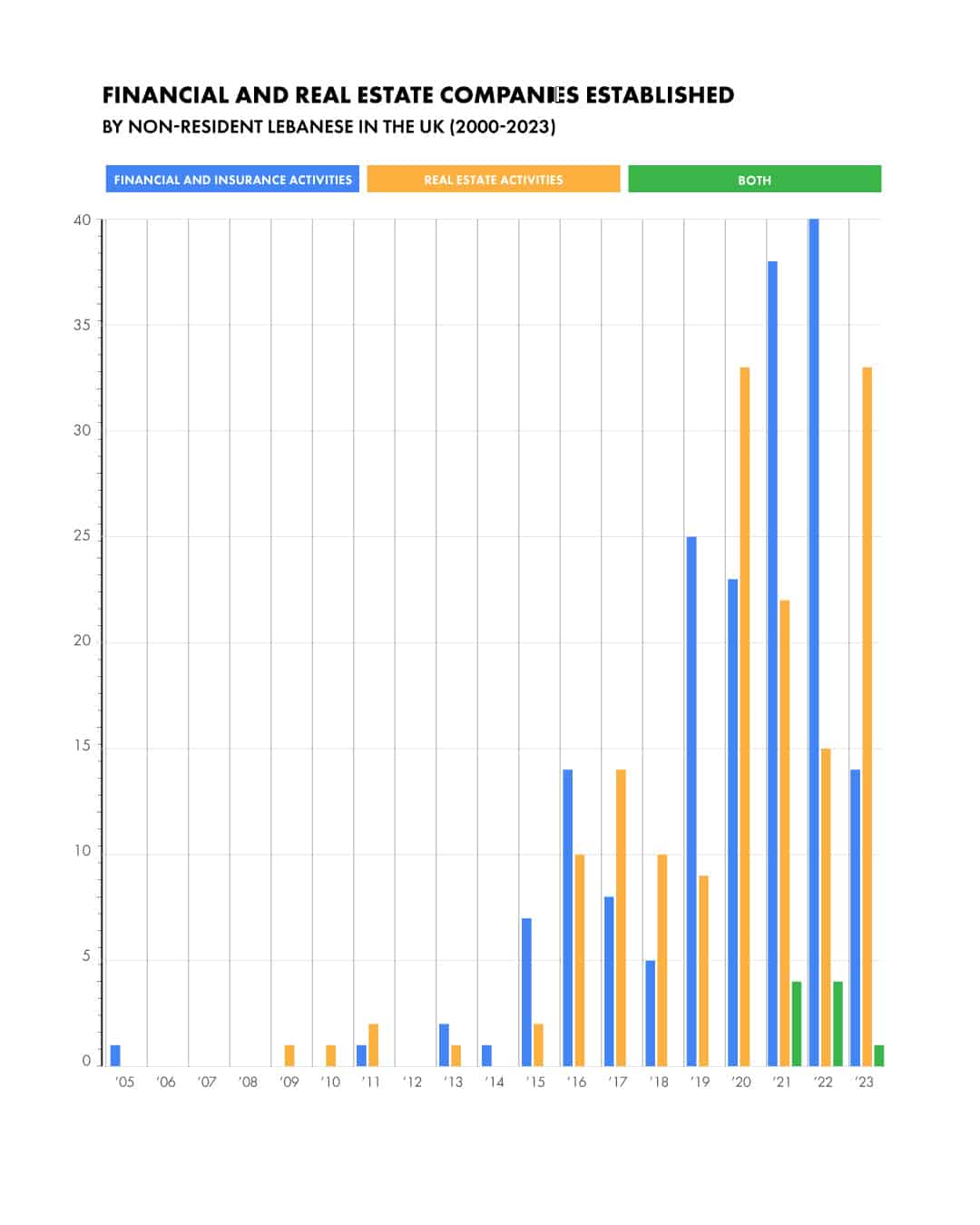

The fact that Lebanon’s political-banking elite have siphoned billions from the public purse over the past decade is already well known. What remains more elusive, however, is where they stashed all the money. This Badil analysis of international business registries and other financial documents reveals the likely answer: much of it was funneled into offshore companies, hidden in jurisdictions designed for opacity, by the very elites who engineered and enabled the country’s 2019 financial collapse.

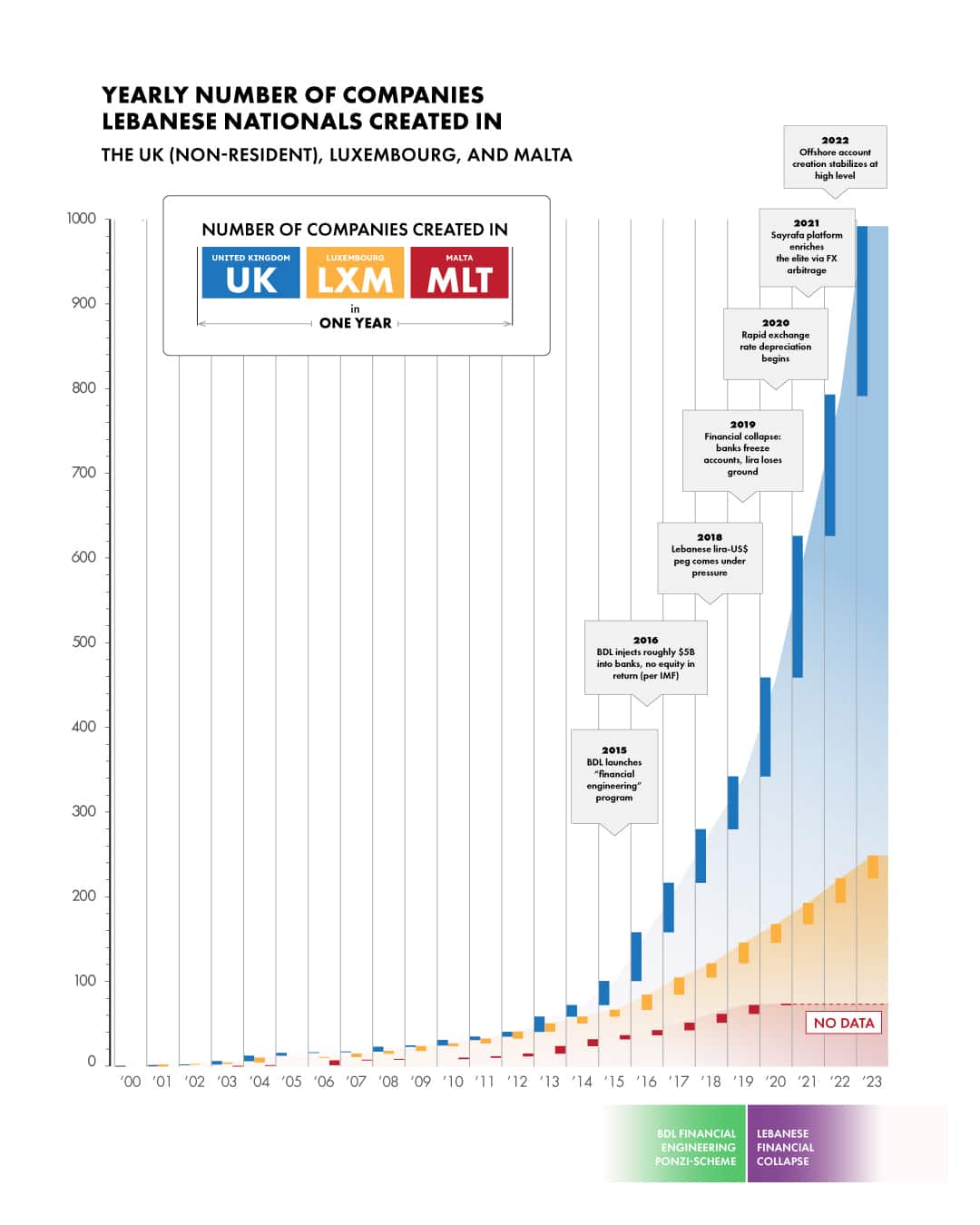

The 2021 Pandora Papers revealed the Lebanese elites’ penchant for moving their money out of the country, showing that Lebanese nationals registered more offshore companies than any other country on the planet – more than twice the number of the next closest nation, the United Kingdom. Badil’s analysis of public and private business registries in the UK, Malta, and Luxembourg has now uncovered in detail the incredibly suspicious timing in which these companies were created: the number of Lebanese registering offshore companies jumped after 2015, and then skyrocketed around 2019.