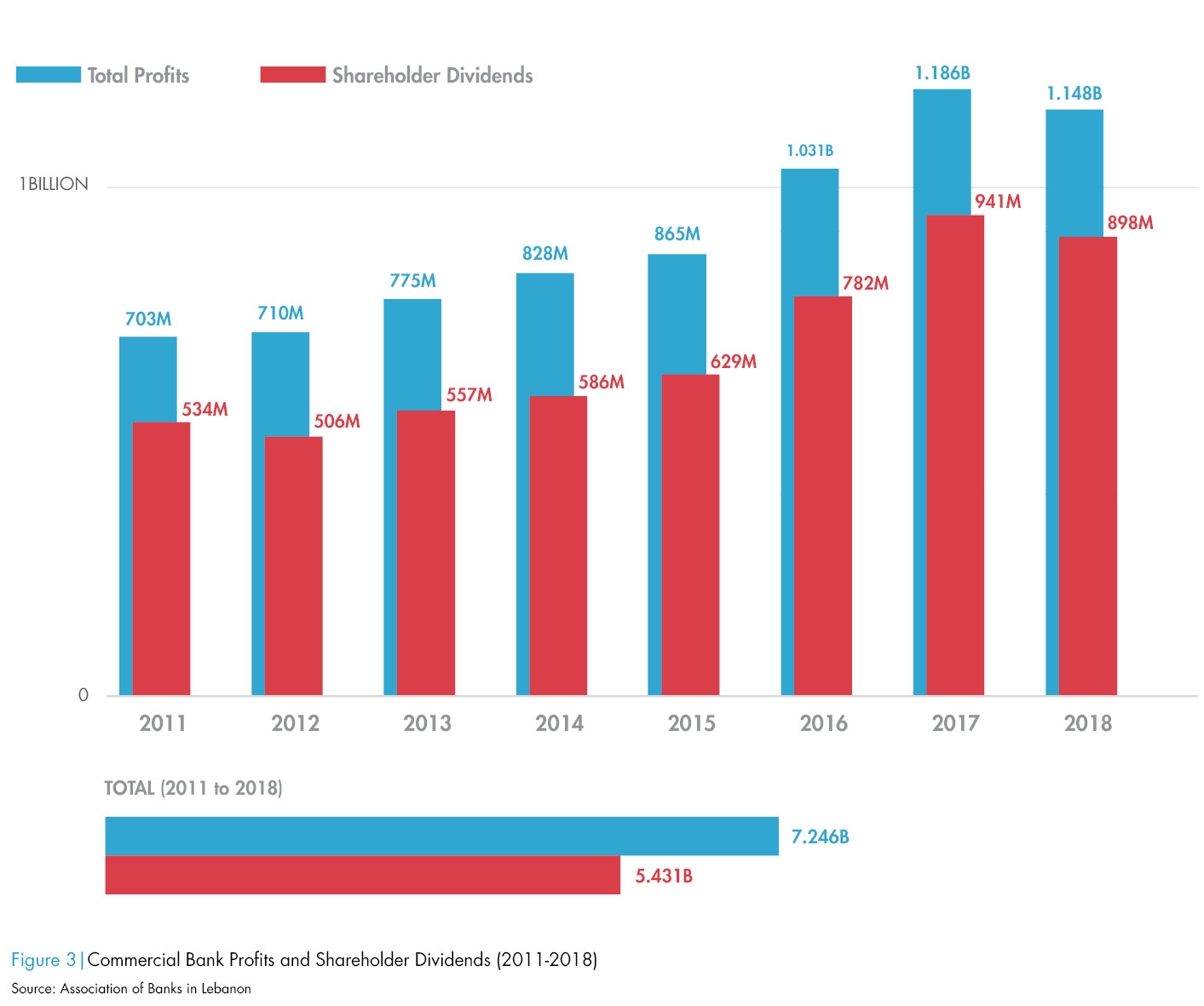

This outrageously high dividend payout ratio, which precluded most reinvestment in core business operations, indicates that the banks acted far more as syphons feeding cash to shareholders than as commercial operations. This reckless profiteering directly contributed to the banking sector’s insolvency and warrants a clawback on dividend payments. Shareholders who fail to comply with the dividend clawback will face legal asset seizures in Lebanon and, when possible, abroad.

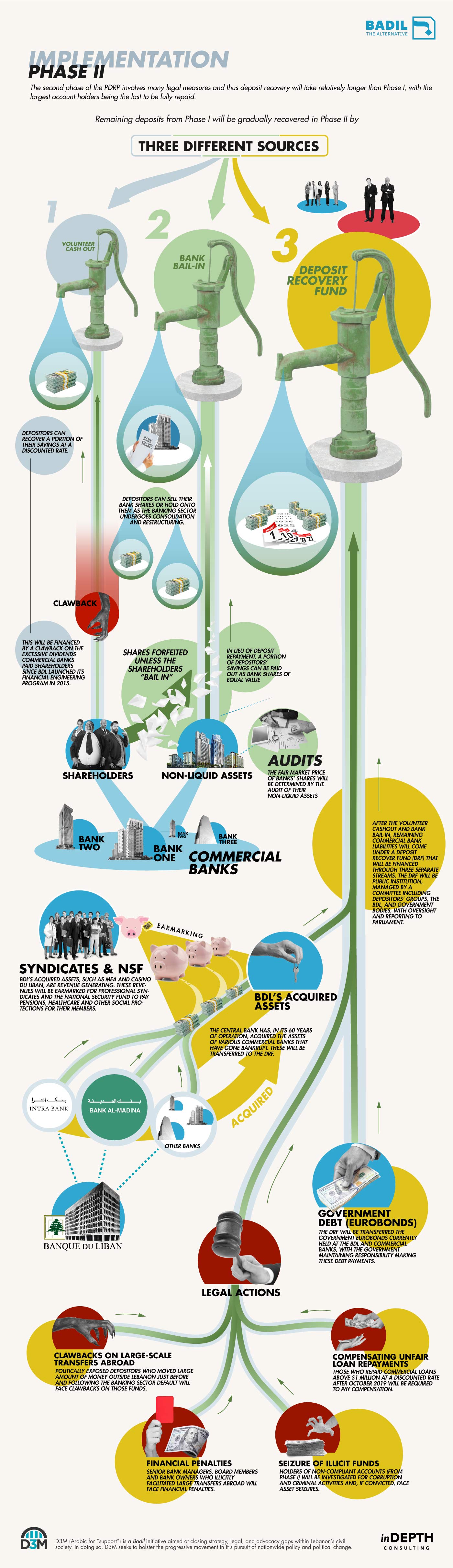

Bank Bail-in

The comprehensive audit of commercial banks will offer an account of all bank assets, both liquid and non-liquid. While the former will be distributed in Phase I of the deposit recovery plan to immediately pay back small depositors, the latter will allow for the determination of a bank’s fair market value.

Due to the bank failures, existing shareholders have lost their rights to their equity stakes, which will be forfeited unless the shareholder “bails in”, meaning they put in new capital equal to the value of the shares they wish to maintain. For depositors, in lieu of deposit repayment, they can receive forfeited shares in their bank equal in value to the deposits they opt to “bail in”, with shares priced relative to the bank’s fair market value. Depositors can then sell these shares or choose to hold onto them as the Lebanese banking sector undergoes consolidation and restructuring. Importantly, each bank will, as an institution, maintain some capital for operational purposes

.

Deposit Recovery Fund

The remaining outstanding commercial bank liabilities will come under a Deposit Recovery Fund (DRF). The primary difference between this deposit recovery plan and that which the Lebanese government proposed in April 2020 is that the latter called for public assets, revenues – and potential oil and gas revenue – to finance deposit recovery, while this plan opposes any public assets or revenues being used to cover commercial bank loses.12 This aligns with the international standards adopted in the wake of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. The three financing streams for the DRF will be:

1. Government debt: All government issued Eurobonds held by the commercial banks and central bank will be transferred to the DRF, with the government maintaining responsibility for paying down this liability. This is the government’s only financial contribution to the PDRP. A payment schedule for these Eurobonds can only materialize, however, after negotiations with all Eurobond holders – including international debt holders – are held to determine, among other things, the real market value of the bonds.

2. The BDL’s acquired assets: Over the course of the Lebanese central bank’s existence, various commercial banks in the country have fallen into bankruptcy. Some of the more notable examples have been Intra Bank and Bank Al Mashrek. By law, the BDL has seized control over these banks and all their assets. This is how BDL came to have controlling stakes in commercial enterprises such as Casino du Liban and Middle East Airlines, among others. These “acquired assets” are revenue-generating and their ownership will be transferred to DRF. It is important to emphasize that this does not signify privatisation in any way, but rather is a shifting of ownership from one public body to another. The revenue-generating assets of banks declared insolvent through the PDRP process will also be transferred to the DRF. The recurrent revenues these assets provide will be earmarked for the immediate and exclusive use of Lebanon’s professional syndicates and the National Social Security Fund to offer healthcare, pensions, and other social protections to their membership until these large deposit holdings are restored.

3. Legal actions: Likely among the most complex, time intensive and politically fraught aspect of the deposit recovery plan will be the legal actions against those who caused, benefited, and continue to benefit from the financial crisis. This step, however, is also the most important for accountability. The legal actions will fall roughly into four main categories:

a. Clawbacks on all large-scale transfers out of the Lebanese banking system in the months just prior, and in the years following the commercial banks’ default in October 2019: In March 2019, commercial banks began implementing processes that made it increasingly more difficult for most depositors to withdraw savings, and in October that year blocked withdrawals for these depositors almost entirely. In parallel, however, the small number of depositors with more than $100 million in their accounts were able to move more than $5 billion out of the Lebanese banking system between June 2019 and November 2022.13 The comprehensive audit will allow precise details of these transfers to become available. Politically exposed large depositors who withdrew significant portions of their funds immediately preceding the default will be investigated for having illegally benefited from insider information. Large transfers following the commercial bank default amount to depositor discrimination – letting some people access their funds and not others – and is illegal under Lebanon’s Law of Money and Credit. Those found to have illegally transferred funds will be subject to clawback. Depositors who fail to comply with the clawback will face asset seizures in Lebanon and, when possible, abroad.

b. Financial penalties against those who facilitated illegal transfers and those who benefited from them: The former category will include senior bank managers, board members and owners of commercial banks, while the latter will include politically exposed people (PEPs) who leveraged their connections and the power of their office to have their funds moved abroad.14 Financial penalties will be calculated as a percentage of the funds transferred, with the amount dependent on the difference between what was found to be illegally transferred and what is not yet recovered. This arrangement will incentivize cooperation with investigators. Those who cooperate further to aid the investigation can also negotiate clemency. Those who fail to pay the financial penalties will be subject to asset seizures in Lebanon and, when possible, abroad.

c. Seizure of funds generated from illicit activities: Holders of non-compliant accounts (as outlined in Phase I) will be investigated for corruption and criminal activities, and where appropriate subject to asset seizures. The focus will be on politically exposed people, senior public servants, bankers, and affiliates of all these individuals. The intent is to hold accountable those whose invested authority, or proximity to power, allowed them to benefit from corruption, nepotism, and general pilfering of Lebanese public funds. Where necessary and possible, investigations will extend internationally to track down illicit funds transferred outside of Lebanon.

d. Seeking compensation for commercial loans above $1 million that were settled at local banks after October 2019 at a discounted rate: The lion’s share of commercial loans was concentrated in several dozen borrowers when the crisis began in October 2019. When the US dollars stuck in Lebanese banks – so-called “lollars” – began to fall in market value, a secondary market arose whereby loan holders sought to settle their dues at the banks through purchasing lollars at a discounted rate. [As a theoretical example, Company X would pay $500,000 in cash to Company Y for a cheque written out for $1 million, which Company X would then put against its commercial bank loan.] Over time, the price of the lollar collapsed to just 10 percent, with a $1 million cheque now priced at just $100,000. The commercial borrowers are estimated to have benefited by up to $15 billion from this implicit subsidy.15 This constituted a wealth transfer from depositors to commercial borrowers, given the depletion of real dollars on the banks’ books and the consequent decline in recoverable deposits. Commercial loan holders who benefited in this manner should be incentivized to compensate for it, be taxed accordingly, or have countervailing fees placed upon their business operations in Lebanon. In any case, this money would be put toward the DRF.

The DRF will be a public institution managing large amounts of funds, and thus should be subject to a high degree of monitoring and transparency mechanisms. Potential fund management setups could involve depositors’ groups and representatives from the BDL’s Banking Control Commission of Lebanon and Special Investigation Commission, the Parliamentary Budget and Finance Committee, the National Institution for the Guarantee of Deposits, with oversight from and reporting to parliament. At a minimum, transparency mechanisms should include an annual report that gives a detailed outline of the fund’s initiatives and how close it is to fulfilling its mandate.

In the long term, following full depositor repayment, what happens with the DRF’s remaining revenue streams will need to be decided. Potential options would include the creation of a publicly-owned union bank; bringing it under the purview of a sovereign wealth fund, or placing it under a subaccount at the central bank.

Maintaining the BDL and a Viable Commercial Banking Sector

Following the BDL’s contribution to the near-term payout – that being the required reserves the commercial banks have deposited at the central bank – all BDL liabilities to the commercial banks will be considered resolved. The DRF envisions a recapitalization of the central bank akin to the government plan to allow the central bank to maintain core monetary policy functions.

To recap, in Phase I of the PDRP, the central bank will contribute the available reserves it holds to the near-term depositor payout. In Phase II of the PDRP, the BDL will then relinquish its acquired assets and Eurobonds to the Deposit Recovery Fund. The central bank will then be left with the gold reserves and other assets intact. A 10 percent reserve requirement for commercial banks that remain in operation (discussed below) will also be held at the BDL. The Lebanese government, as per its own plan, will then recapitalize the BDL by $2.5 billion.

In regard to the commercial banking sector, while the PDRP discusses it in aggregate on the assumption that the sector is generally insolvent, provisions are made for individual banks to continue to operate. To do so, they must pass three successive criteria stages (discussed below) that will remove them from the wider PDRP process by having them repay the liabilities of their specific depositors.

First, the bank must be able to fully repay all their depositors below the threshold for immediate repayment. Next is the “bail-in” stage, where remaining depositors are either transferred the shares of existing shareholders as compensation for their deposits, or if the bank wants to keep its current shareholder structure, it must undergo a recapitalization. This would involve the shareholders injecting fresh funds into the bank, equivalent to the value of the shares maintained, with this money then going to repay depositors.

Should a bank successfully accomplish these two steps, the bank will be transferred back its share of the liability in the DRF, as well as the bank’s previously held Eurobonds, thereby maintaining both its liabilities and assets. The bank will then need to raise enough funds to meet a new capital adequacy ratio. For example, if a bank’s share of DRF liabilities is $2 billion, and the new capital adequacy ratio is 3:1, then the bank will be required to raise $700 million in fresh capital for its balance sheet. A portion of all future profits will then be earmarked for meeting the banks liabilities to existing depositors until all are repaid.

In spite of the current crisis, Lebanon’s commercial banks will be a necessary core of any economic recovery moving forward, and the PDRP process seeks to separate those that are willing and able to continue providing their essential financial services from those that are not.

Looking Ahead

Lebanon’s insolvent banking sector will require massive consolidation and restructuring moving forward, a crucial issue that is beyond the scope of this paper. The country will also require a blueprint to address longstanding macroeconomic weakness for successful long-term rehabilitation from the ongoing financial crisis. But neither this, nor banking sector restructuring, can take place before a just solution is found to restore what the banking and political elite so blatantly stole from the population.

The plan outlined here will not be an easy pill for many to swallow. It is imperfect and will be vulnerable to criticism. Economic desperation has already driven more than a million small depositors to withdraw their savings at haircuts that reach up to 90 percent of their original deposits. These were, in many cases, the poorest of depositors who had no other means of recourse, and this plan does not address the losses they were unjustly forced to bear. For those who do see their savings restored, in return they will have to forego any other individual legal claims they may have against the commercial banks, regardless of the merit such claims hold.

And while the plan seeks to recoup funds and impose financially punitive measures on those responsible for and benefiting from the crisis, it also provides them opportunities for leniency in exchange for cooperation. The reasoning for this is that the banking and political elite must be provided with some path forward for themselves that does not leave them destitute and in jail, lest they dig in their heels and prevent the plan from moving forward at all.

Further international sanctions beyond the former BDL governor have the potential to build impetus and align the necessary stakeholders behind a politically viable and socially acceptable solution for Lebanon. The progressive deposit recovery plan offered above is a first step on the country’s long road to recovery with many sacrifices.

These are sacrifices that must be made to move the country forward, because as we wait in stalemate the informal economy grows and the chances of the government ever being able to fund itself diminish, which serves no one. Indeed, the longer the status quo continues and the country atrophies, the closer Lebanon comes to true failed statehood where a return to violent civil conflict takes only a spark. The window of opportunity to avoid this outcome is closing; and that’s why Lebanon needs a realistic, fair, accountable and progressive deposit recovery plan.

This paper was compiled with the support of the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.