EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In summer 2021, Lebanon had no room for doubt about the immense power of local oil importing companies. The country’s fuel crisis, which brought nationwide services to a standstill, led the desperate, sweltering public to start monitoring the oil sector’s every move. They waited anxiously for oil tankers to deposit their cargo on Lebanon’s shores. They hoped that oil importers would reach agreements with Lebanon’s central bank, Banque du Liban (BDL), to finance new shipments. And they stood powerless amidst reports of private companies hoarding fuel supplies or smuggling them to Syria.

Over the previous three decades, Lebanon’s post-war reconstruction had been centred around oil dependence. Successive governments prioritised projects that maintained high fuel consumption levels – such as heavy investment in road infrastructure – and failed to support more efficient, alternative forms of shared transport and energy production. At the same time, Lebanese businesses and individuals received generous state subsidies on fuel, which blinded them to the true cost of imported oil.

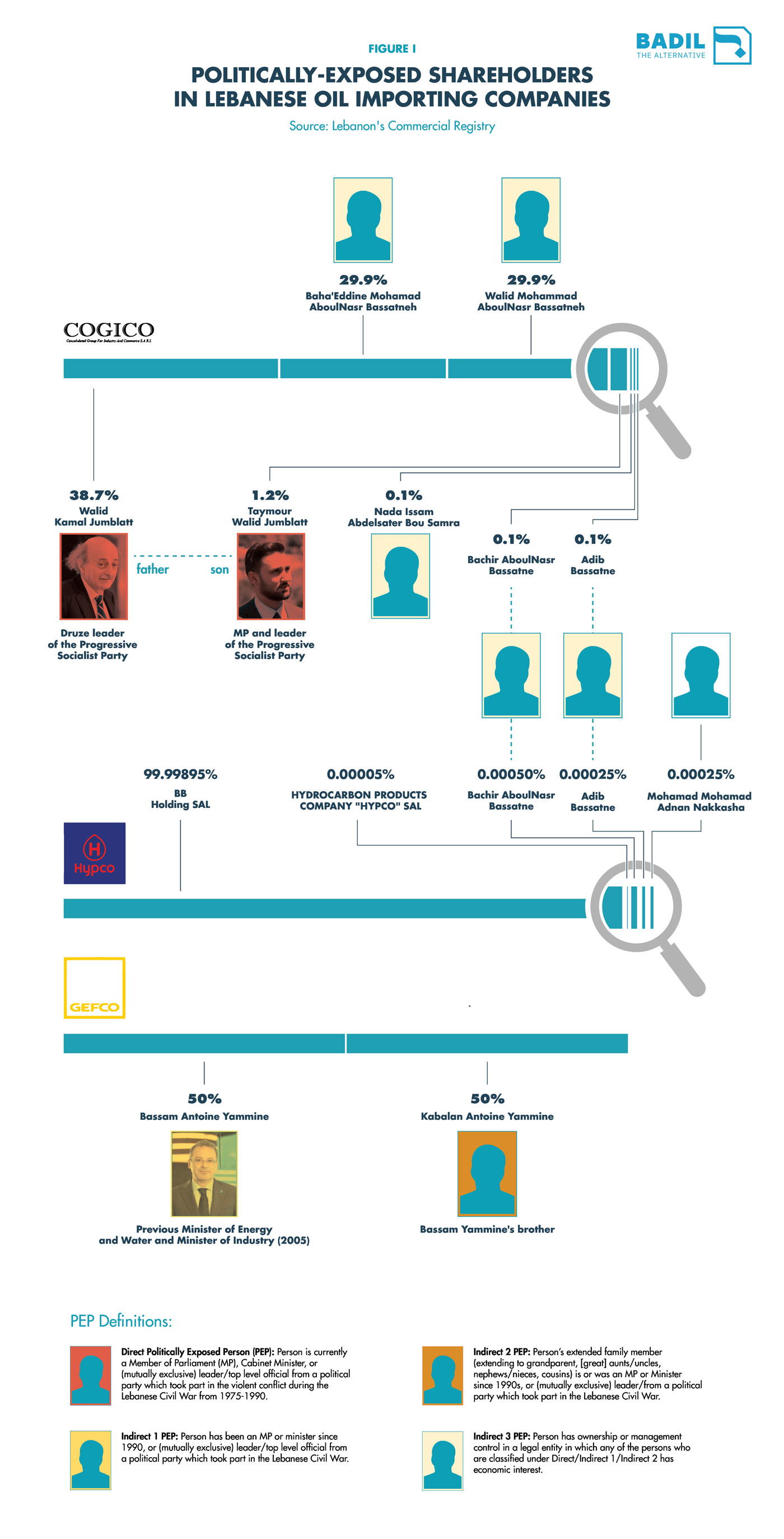

Unsurprisingly, Lebanon’s political elites benefit directly from presiding over a hopelessly oil-dependent country. At present, an oligopoly of 13 importing companies dominates the sector – several of whom have blatant, demonstrable links to politicians or sectarian leaders. Commercial Registry records reveal that politically exposed people (PEPs) are current directors and / or shareholders in Cogico, Gefco, and Hypco. Various reports suggest that conflicts of interest loom over other oil importing companies, facilitating still more undue influence over political decisions that impact the oil sector.

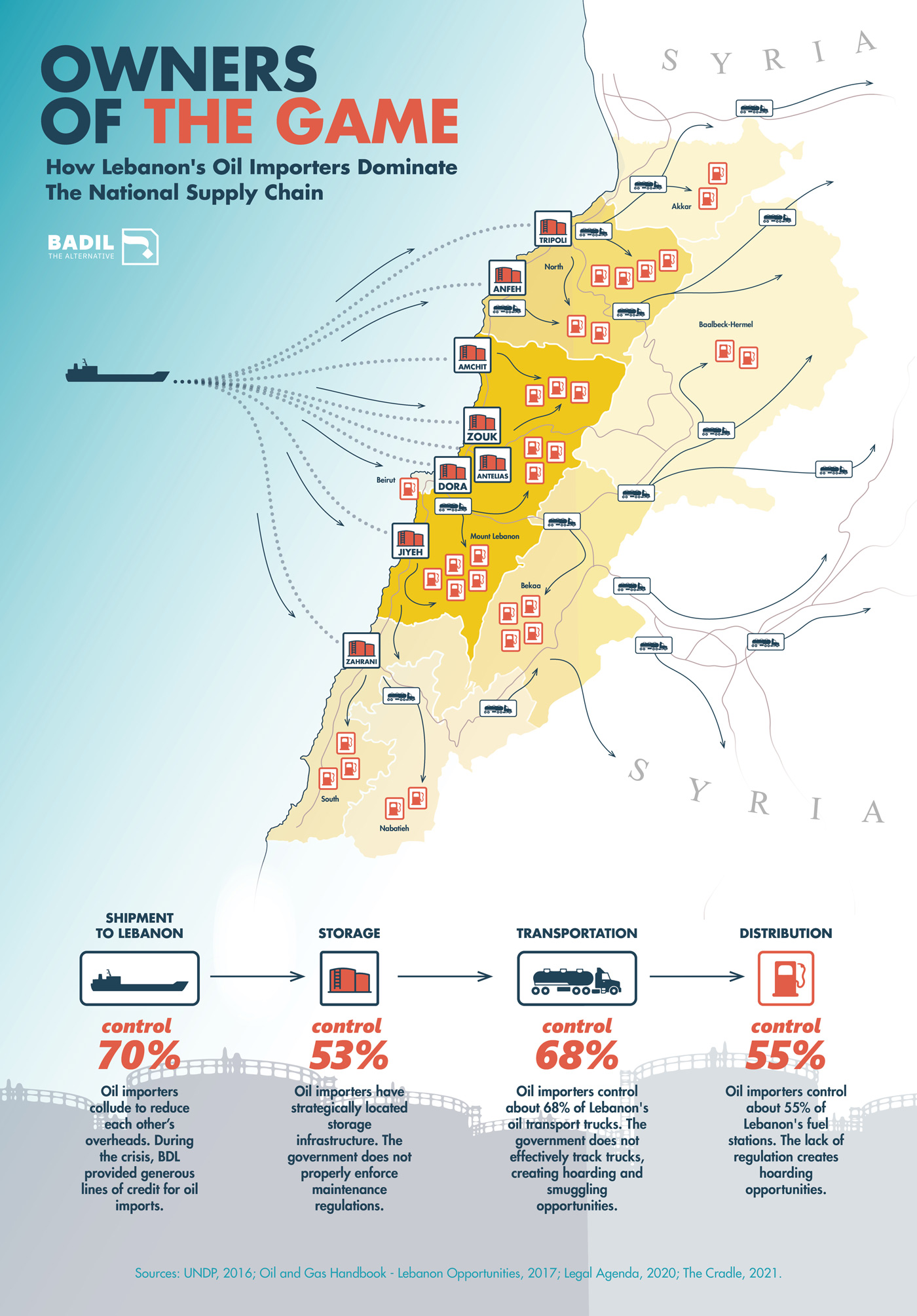

With powerful connections in place, Lebanon’s oil importers have secured dominant positions over the entire oil supply chain. These companies benefit from state licences to import oil products to Lebanon, do not face stringent enforcement of storage maintenance regulations, and can transport and distribute oil with virtually no government scrutiny. And, of course, oil importers have long profited from the state’s fuel subsidies, which have given their customer bases wildly inflated purchasing power.

Lebanon’s economic collapse has underscored, rather than challenged, the power of local oil importers. As foreign currency grew scarcer, oil companies received from BDL favourable credit lines in US dollars for import purchases. Importers complained about late payments from BDL out of the country’s dwindling reserves, while commanding high profit margins between March and September 2021. Even the final withdrawal of fuel subsidies has not cowed these companies, which retain their dominant infrastructure and political allies.

Despite these advantages, even Lebanon’s oil importers cannot ignore a growing public appetite for change. Across the country, well-off households have started installing solar panels to cut down on diesel generator bills. Commuters are not using private cars as much as before. Opposition groups and activists must seize this zeitgeist to insist that the government finally bring the oil sector to heel. Crucial steps include creating an independent competition regulator, penalising companies for legal violations, and tracking oil transportation and distribution.

Ultimately, this groundswell must build towards reducing Lebanon’s overall oil dependence. After all, oil importers can no longer hold a country hostage if people stop caring how much fuel comes out of the bowser.

POLITICAL CONNECTIONS

Since the civil war, a handful of fuel importing companies – often linked to warlords turned politicians – have established an oligopoly over the local oil market. Today, the country’s 13 licensed oil importers control an estimated 70% of national oil volume, while the government’s oil facilities make up the remaining 30% of the market.1 For decades, public and private figures have repeatedly colluded to ensure that the oil sector remains highly lucrative – often at the expense of Lebanese state finances.

While the state maintains confidentiality over these arrangements – including through BDL failing to comply with freedom of information requests made for this report – evidence has emerged of the oil cartel’s existence. For example, a comprehensive 2003 study based on VAT receipts (the latest of its kind) found that three companies controlled 93% of Lebanon’s market for liquid fuel.2 More generally, media reports surface regularly that uncover scandals plaguing the oil sector (See Box: Dirty Business).

These unpalatable circumstances become predictable considering the long-term, embedded conflicts facing key powerbrokers in the oil industry. Conflicts of interest describe situations where an individual or company can exploit their professional or official capacity in some way for personal or corporate benefit.3 In Lebanon’s oil sector, a significant number of key figures are (or reportedly are) politically exposed people (PEPs), indicating close links between their commercial interests and public policymakers (See Box: Defining Conflicts of Interest). In short, PEPs in Lebanon’s oil sector likely have enough leverage to influence political decisions affecting the sector – without claiming, of course, that all PEPs exploit these relationships.

This report outlines these conflicts of interest, identifying three companies that have objectively defined PEPs in positions of power (See Figure 1). These links were ascertained through Lebanon’s Company Registry, and an analysis of ownership (shareholders) and management (boards of directors) of various companies involved in the oil importing sectors. A further three companies have reported links to political figures.

- Direct Politically Exposed Person (PEP): Person is currently a Member of Parliament (MP), Cabinet Minister, or (mutually exclusive) leader/top level official from a political party which took part in armed conflict during the Lebanese Civil War from 1975-1990.

- Indirect 1 PEP: Person has been an MP or minister since 1990, or (mutually exclusive) leader/top level official from a political party which took part in the Lebanese Civil War.

- Indirect 2 PEP: Person’s extended family member (extending to grandparent, [great] aunts/uncles, nephews/nieces, cousins) is or was an MP or Minister since the 1990s, or (mutually exclusive) leader/from a political party which took part in the Lebanese Civil War.4

- Indirect 3 PEP: Person has ownership or management control in a legal entity in which any of the persons who are classified under Direct/Indirect 1/Indirect 2 has economic interest.5

The most overt example of how key politicians have an economic interest in Lebanon’s oil importing sector is Cogico. The company is partly owned by Progressive Socialist Party’s (PSP) Walid and Taymour Jumblatt, the latter of whom also sits on Cogico’s board of directors. Walid Kamal Jumblatt owns 38.7% of the company, while his son – the PSP heir and MP – Taymour owns 1.2%. The other Cogico shareholders, who are mostly from the Bassatne family thus have common business interests with politically exposed persons, creating conflicts of interests.