EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

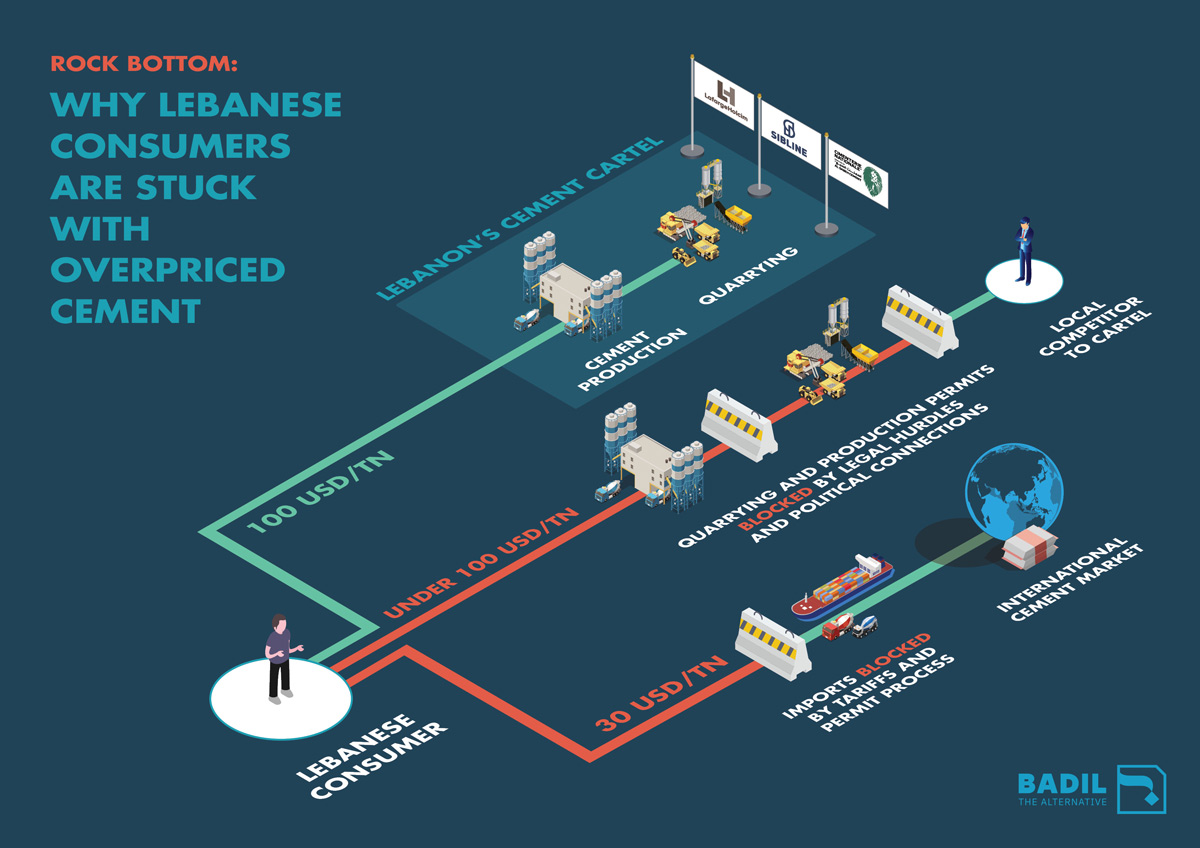

For decades, Lebanon’s economy has overwhelmingly served the interests of certain economic actors, who preside over widespread monopolies and oligopolies. This endemic imbalance of power reflects a country where unfair competition is rife, allowing powerful groups to maximize their profits at the expense of everyone else. For instance, a bag of cement in Lebanon has long cost around triple the international market price. Why are Lebanese consumers paying so much more for the same product? The simple answer is that they have no other choice, due to a lack of proper market competition.

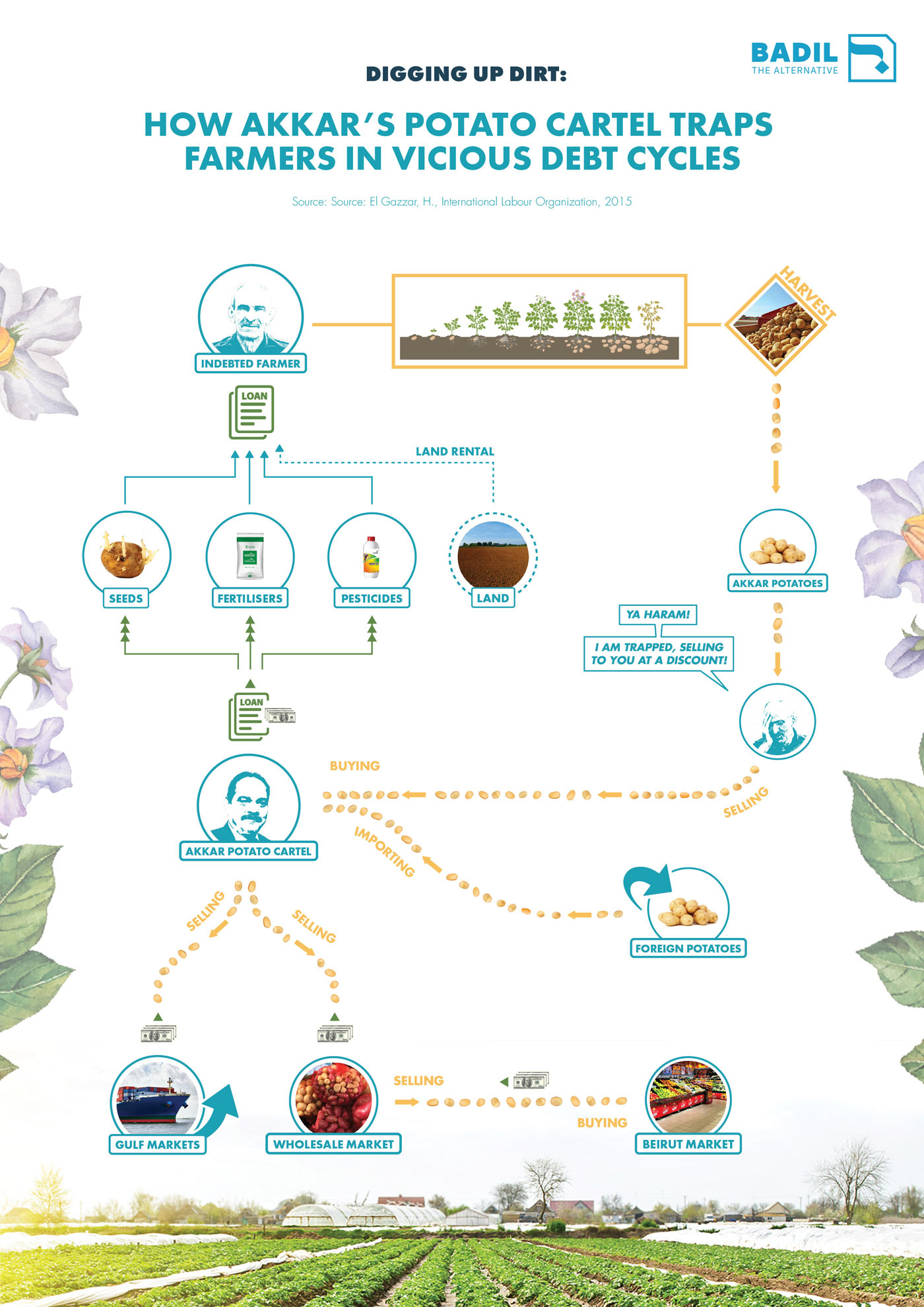

In other industries, unfair competition has long meant that vulnerable workers lose out. In Lebanon’s northern Akkar governorate, one of the poorest in the country, a powerful trading conglomerate controls large parts of the local value chain for potato farming.1 The oligopolists lock vulnerable farmers into a “closed loop,” in which they can only sell their produce to a specified trader at a reduced price. These practices ensure that, by slashing farmers’ profit margins, consumers pay lower prices for potatoes. But the overall economy still loses out, as small-scale growers have precious little capacity or incentive to invest in improving the nation’s agriculture sector.

While these endemically unfair markets have persisted for decades, the past year’s tumultuous events have thrust sweeping change upon Lebanon, bringing an economic correction. As the nation grapples with an unprecedented economic crisis, even oligopolists must adapt to new commercial realities. The cement cartel has largely accepted government demands to lower prices, given the inability of consumers to continue

meeting their extortionate rates. In Akkar, powerful potato scions can no longer entrap small-scale farmers in vicious debt cycles, because it is no longer viable to extend lines of credit for agricultural inputs.

Although these developments have shaken long- standing practices of restricting competition, the fundamentals of these exploitative value chains remain standing. Lebanon’s cement companies have temporarily priced their products more affordably, yet they still benefit from enormous, state-sanctioned barriers to entry for would-be competitors. Small- scale farmers still lack viable alternatives to entering a rigged debt cycle to continue farming, even if those loan schemes have halted for now. The root causes of unfair competition continue to underpin both sectors, ready to be reactivated – and re-exploited – when Lebanon’s economic situation eventually improves.

This paper explores how unfair competition in Lebanon works in practice, with reference to value chains for potato production in Akkar and national cement production. The path to addressing these kinds of monopolist practices lies in establishing a comprehensive competition law and policy, appropriately adapted to the Lebanese context. Despite more than 15 years of debate, Lebanon’s draft competition law still gathers dust inside a parliamentary desk drawer.

Unfair competition in Lebanon is a veritable Medusa, whose snake-ridden hair represents the myriad shady business interests that preclude economic development – all in the name of petty individual gain. Confronting this commercial monster requires nothing less than a resolute competition law, a dynamic competition authority and heroic levels of political commitment.

PUMPING UP THE COMPETITION

Since time immemorial, Lebanon has been riddled with oligopolies2 — or, “the monopoly of the few.” A comprehensive 2003 study (the latest of its kind) concluded that half of Lebanon’s domestic markets are considered either oligopolistic or monopolistic.3 This means that consumers have limited scope to shop around for alternative vendors when purchasing goods or services.

The key yardstick for competition is how easy (or difficult) it is for a new company to establish itself in a given sector. Barriers to entry can be natural, such as a lack of customer demand or intensive start-up capital requirements.4 Yet they can also be artificial, stemming from onerous legal and administrative rules, or cynical business practices that snuff out potential competitors.5

By international standards, Lebanon has weak legal frameworks for promoting market competition.6 The country has no independent competition authority tasked with stamping out anti-competitive business strategies.7 While it is illegal to “limit competition … resulting in an artificial increase in prices,” this provision lacks specificity and is difficult to establish in court.8

Similarly, the Lebanese government shows little appetite for punishing price gouging, a practice in which sellers charge their customers unfair prices in reaction to a supply dip or demand spike. While Lebanon’s Consumer Protection Directorate is empowered to enforce ceilings on profit margins,9 in practice, it does little to deserve its name. On average, the taskforce annually issues around 200-500 fines for consumer welfare violations; the equivalent body in Dubai hands out around 17,000 infringements every year.10

BOX I: Healthy Competition?

In general, an appropriate level of competition between companies confers a range of social and economic benefits. Companies cannot overcharge their customers, lest they shift to buying the same goods from a rival competitor. Healthy competition also drives businesses to operate more efficiently, which tends to strengthen the overall economy.i Importantly, however, there is no point having rife competition for the sake of it. The level of competition must be “workable,” such that the amount of consumers justifies the number of competing businesses.ii So, while Lebanese consumers might benefit from having more than three cement manufacturers, they probably do not need 100 different options.

This legal vacuum, perpetuated by public officials with ties to certain businesses interests, has ensured that many Lebanese markets remain alarmingly uncompetitive. The country ranked 88th overall out of 141 countries in last year’s Global Competitiveness Index (2019).11 Lebanon performed especially poorly in the “Institutions” category, finishing in 113rd place.12 Weak competition has made much of Lebanon’s economy patently unfair. Riches accrue to monopolists, who can exploit their dominant market positions at the expense of everyday consumers and vulnerable workers.

THE UNHOLY TRINITY: CEMENT HITS ROCK BOTTOM

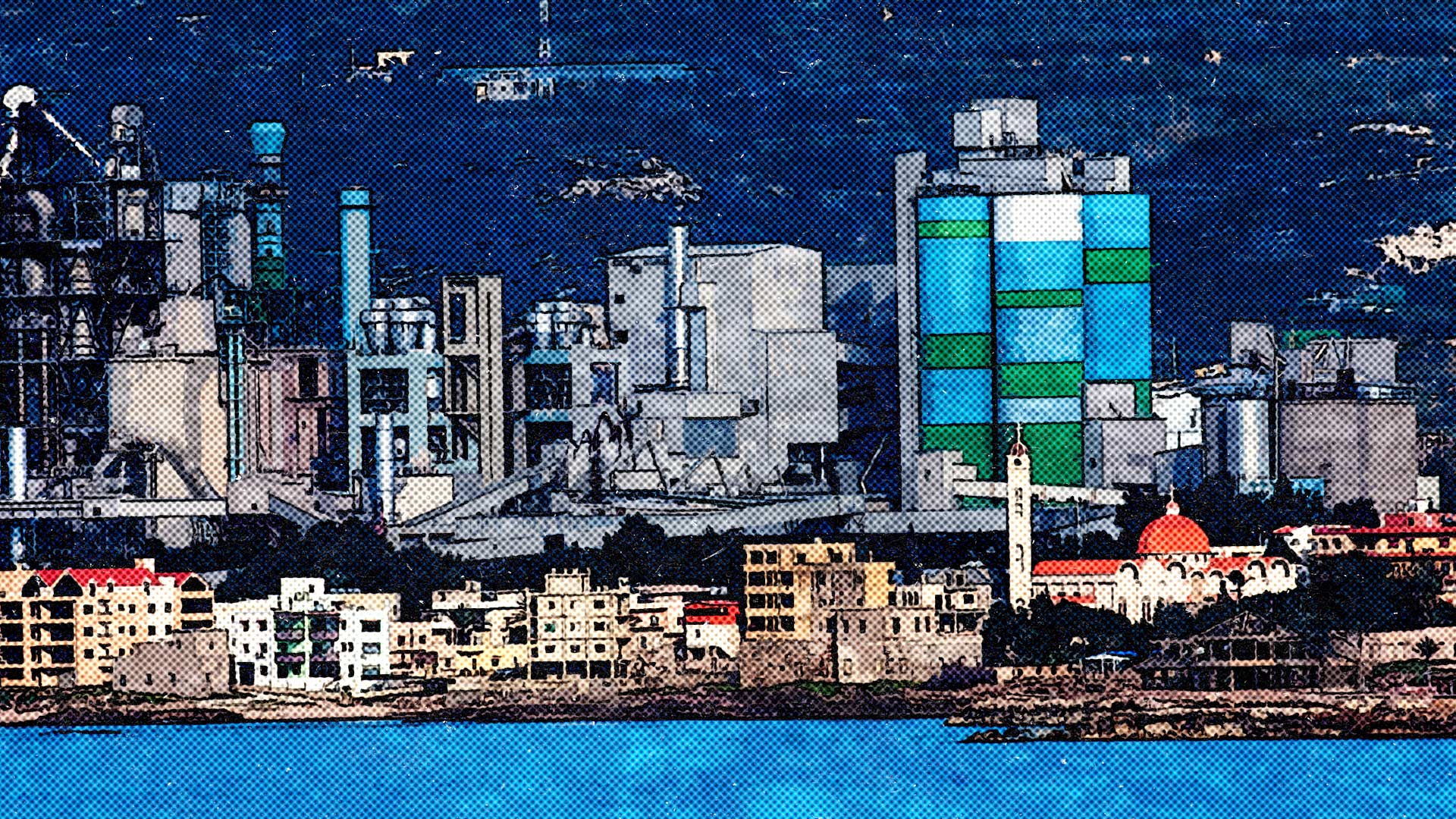

Lebanon’s cement industry is dominated by three companies – Cimenterie Nationale S.A.L., LafargeHolcim Ltd, and Ciment De Sibline S.A.L. – who behave as a classic corporate cartel. Each company oversees a comprehensive operation, dominating the cement production process from start to finish. They extract and crush the raw materials and process those materials into cement, before distributing it abroad or steering its delivery to domestic customers.

Together, the three companies share the entire market for Lebanese cement. In 2015, it was reported that Cimenterie Nationale and LafargeHolcim controlled 44% and 38% of the sector respectively, while Sibline held a smaller stake (18%).13 By colluding together to share the market, they face no competition from businesses outside the cartel.14 The three companies maintain their unrivalled market position courtesy of various artificial barriers to entry, which effectively (or, in some cases, literally) exclude newcomers from the sector. Some of these barriers are legal and administrative, while others stem from the cartel’s informal business practices.

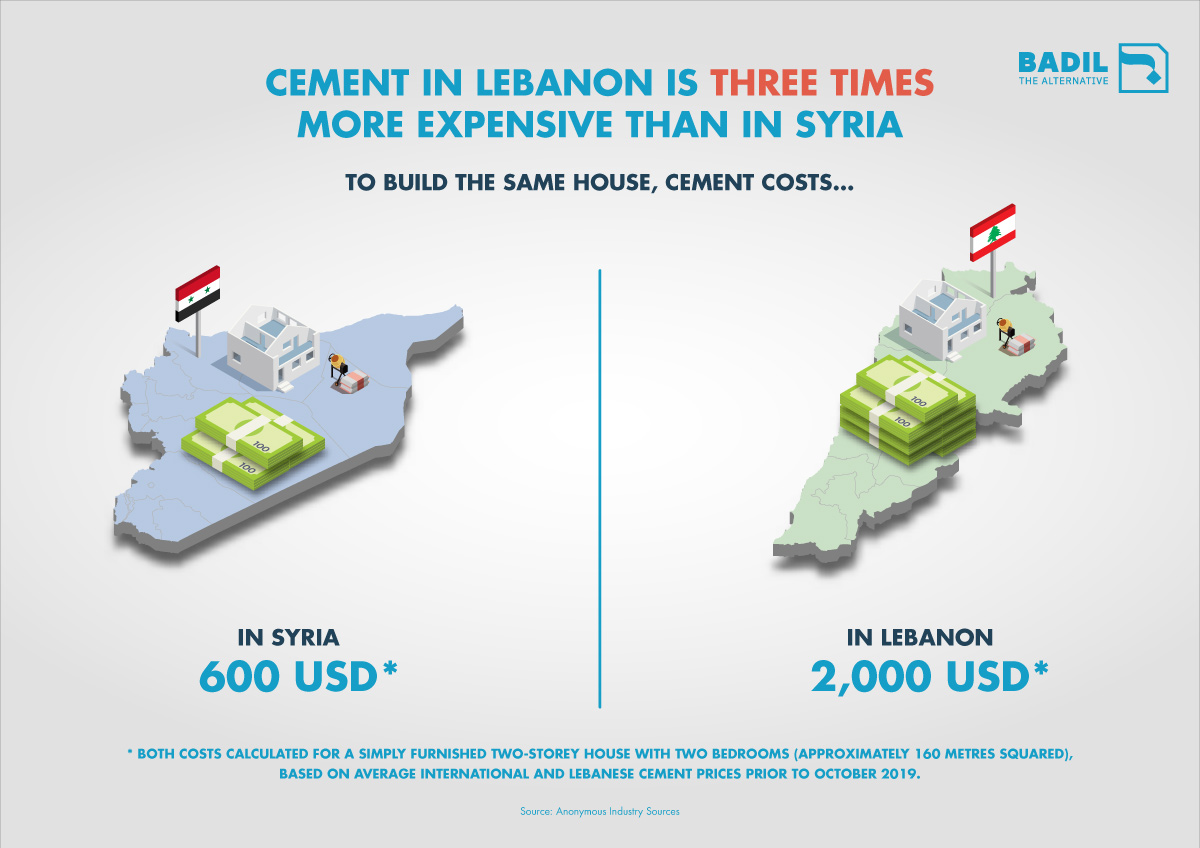

Lebanon’s poor competition framework enables the cement cartel to engage in a variety of restrictive business practices, safe from being undercut by a more principled competitor. First and foremost, the three companies maintain prices at an agreed level, ensuring that consumers can access only one (inflated) price. Before the current economic crisis, a bag of cement in Lebanon cost around triple the international market price.

In Syria, for example, buyers have long paid around $30 for a tonne of white cement — inside Lebanon, it cost as much as $100. Lebanon’s cement companies recoup at least 20% profit from the price of exported cement, according to industry sources. This estimate suggests that the production cost of a tonne of cement is at most $24 – representing a profit margin of some 300%. When approached for information about production costs, product pricing and profits, Cimenterie Nationale, LafargeHolcim and Sibline declined to comment.

At the same time, the cartel has proven itself capable of rapidly reducing cement prices, when it suits them. In some cases, this enables the unholy trinity to twist the government’s arm to achieve its own commerical objectives [See Box II: Set in Concrete].

BOX II: Set in Concrete

In late 2019, Hassan Diab’s new government attempted to make a stand against illegal quarries, many of which provide raw materials to Cimenterie Nationale, LafargeHolcim, and Sibline. In response, the cartel began only selling bags of cement to the few traders and retailers who held cement “coupons.” This created a shortage of cement in the local market, allowing retailers to charge consumers up to 800,000 Lira for a tonne of cement. In August, after the Beirut port explosion, the Interior Ministry allowed illegal quarries to reopen temporarily, on the condition that the cartel would maintain a price ceiling of 240,000 Lira and pay their outstanding taxes. The cement cartel grudgingly agreed to abide by these measures, especially after the government threatened to lift import tariffs. However, sources suggest that, despite the decree, the companies are still selling cement for more than 240,000 Lira.

CRUSHING HOPES: PERMITS FOR LOCAL CEMENT

In defending its domestic oligopoly, Lebanon’s cement cartel has a valuable ally: an arcane system for obtaining government approvals. These opaque processes stand in the way of establishing a new Lebanese cement company, which could provide greater market competition. In effect, the permit regimes act as artificial barriers to entry for would-be commercial rivals to the cement cartel.15

Naturally, there are cogent reasons for imposing approval requirements on any cement sector. As heavy industry, quarries and cement factories should adhere to stringent regulations covering issues like environmental protection and occupational health and safety.16 In Lebanon, however, these permit regimes are often implemented based on cynicism rather than sound public policy.

In theory, any new company hoping to enter the Lebanese cement market would need to obtain a general industrial permit, issued by the Ministry of Industry. The Industry and Environment Ministries rightly classifies cement production as a “Category 1,” industrial establishment, generating “very dangerous impacts on the environment, surroundings and public health which requires moving it away from the households to prevent its impacts.”17 As such, a new entrant would be theoretically subject to a number of different industrial and environmental laws and decrees, just to operate a plant.18 The process for applying for a cement production permit is hardly streamlined, and it has little reason to be; only Cimenterie Nationale, LafargeHolcim and Sibline have ever succeeded in obtaining and keeping this permit.

A new cement company would also need to operate its own quarry. To obtain a quarrying permit, applicants must follow the administrative process set out in Decree 8803 of 2002 and Decision 186- 1 of 1997.19 Under this procedure, each proposal must receive approval from the Governor’s office, the Ministry of Interior and Municipalities, and the local Municipality.20 The local community must also have the opportunity to contribute feedback on the plan.21 Crucially, the proposed quarry can only exist within the “designated zones,” which are deemed as suitable for quarrying purposes.22