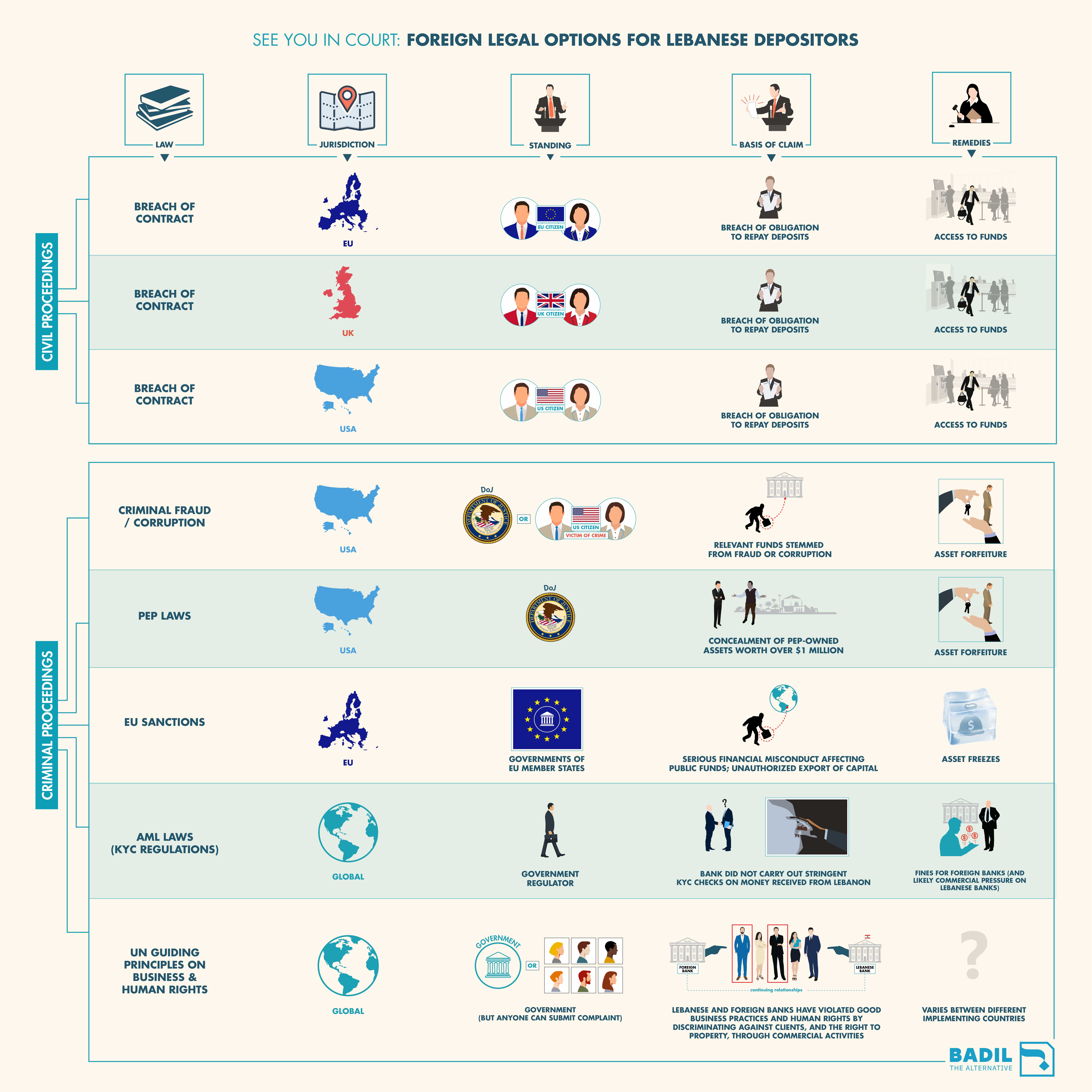

As a first obstacle, claimants need to establish that a US court has jurisdiction over a legal dispute between Lebanese banks and depositors. Unlike EU consumer protection laws, US legislation does not give Lebanese-American citizens a de facto right to bring claims over contracts agreed in Lebanon. In Daou v BLC Bank & Ors, two Lebanese depositors tried to bring proceedings in New York against BDL and three Lebanese banks, alleging fraud and breach of contract. The New York District Court ruled that it did not have jurisdiction to hear the matter, given that the plaintiffs’ contracts were expressly governed by Lebanese law.18 It did not help that the depositors were not New York residents. If they were, the court may have ruled differently. As with European and British cases, American litigants would separately need to prove that Lebanese banks have in fact breached their contractual or other legal obligations.

CRIMINAL PROCEEDINGS

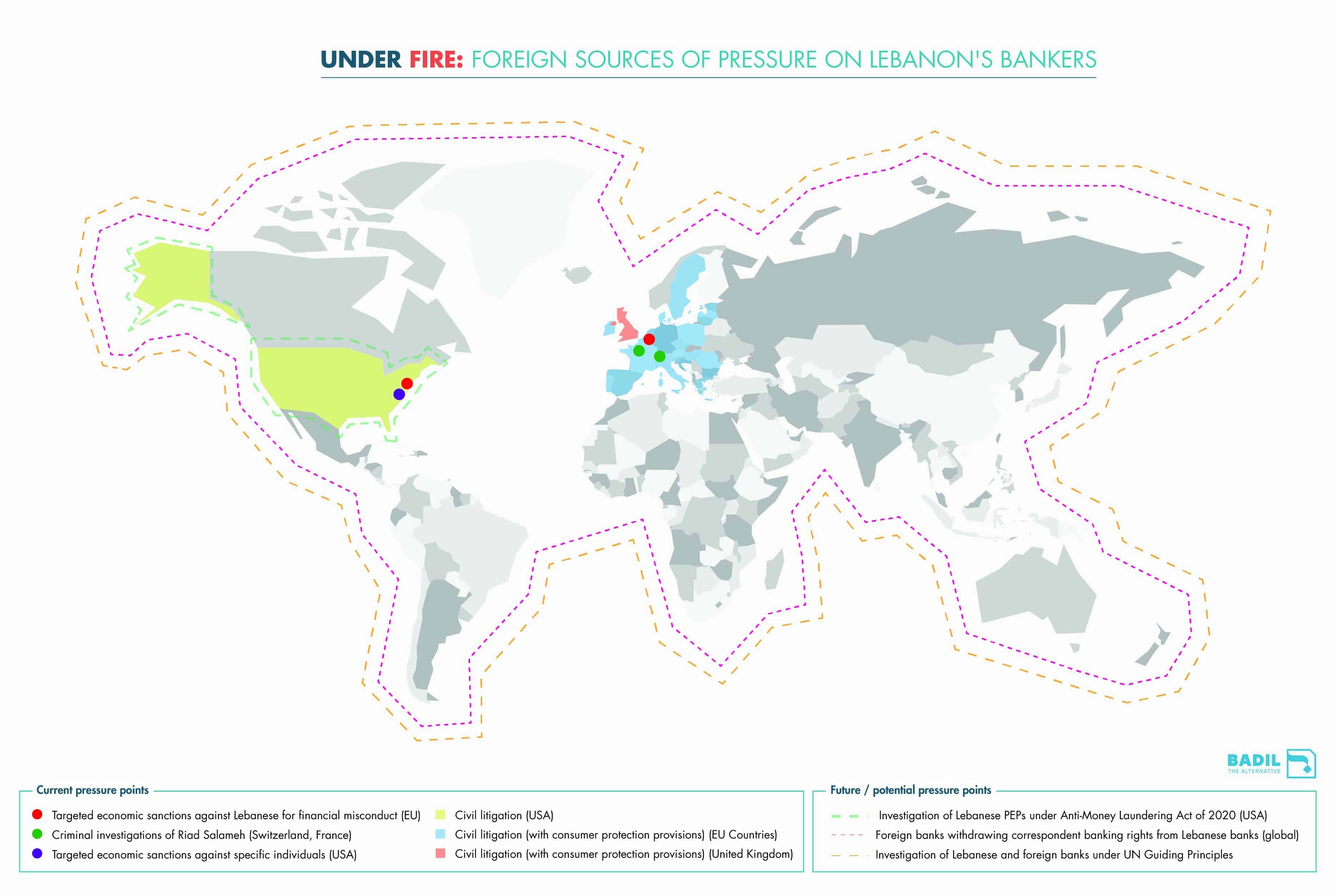

UNITED STATES

Criminal fraud / corruption:

United States forfeiture law provides for asset recovery if the relevant funds are proven to have stemmed from fraud or corruption (as defined under US law). Typically, the Department of Justice would seek asset forfeiture as part of a criminal proceeding. This structure would alleviate concerns about legal fees – after all, the US government does not need to collect contributions from Lebanese depositors – but necessarily relies on the United States taking an active interest the matter. Indeed, usually it would be the local government (in this case, Lebanon’s) that would urge Washington to pursue the case – an unlikely proposition from any post-war Lebanese government. Alternatively, depositors might be able to bring their own proceedings (or petition the DoJ to do so) by arguing that they are “victims of crime.”

Even if asset forfeiture proceedings were initiated, depositors may struggle to provide enough evidence for convicting the Lebanese banks. US forfeiture laws require more than a simple breach of contract. Rather, the DoJ (or depositor claimants) would need to prove that Lebanese banks had engaged in fraudulent or corrupt activities in connection with the deposits. Of course, the DoJ could overcome these evidentiary hurdles by issuing warrants to demand evidence from US and foreign banks, which would likely trump even Lebanon’s banking secrecy law. The DoJ would be unlikely to take this step, however, without strong evidence of fraud or corruption from a whistle-blower or another well-positioned informant.

PEP laws:

New US legislation may provide an avenue for pursuing US-based assets held by Lebanese politically exposed persons (PEPs) – provided that certain conditions are met. Under the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020, the DoJ can bring proceedings against PEPs accused of concealing the ownership of funds over $1 million in US banks. Crucially, the Act does not require that the relevant money derives from a crime, which reduces the evidentiary burden on the DoJ and Lebanese depositors.

By the same token, the DoJ would need strong evidence that Lebanese PEPs had in fact concealed their ownership of funds transferred to US banks; this would likely necessitate a well-placed whistle-blower from inside the Lebanese financial system. If convicted, PEPs face ten years of imprisonment and the forfeiture of any property involved.

While the new PEP legislation offers distinct advantages, procedural questions remain about its application in the Lebanese context. First and foremost, it is not yet clear whether the Act will apply retrospectively – that is, if the law covers transfers to US banks that occurred before the legislation’s enactment in January 2021.19 Moreover, the United States government would not use any assets seized to meet the legal claims of Lebanese depositors, given that there is no direct nexus between PEP’s wealth and the illegal capital controls.

EUROPEAN UNION

Targeted economic sanctions:

In July 2021, the EU Council announced a framework for targeted sanctions, which “provides for the possibility of imposing sanctions against persons and entities who are responsible for undermining democracy or the rule of law in Lebanon.” The sanctions cover acts including “serious financial misconduct concerning public funds” (as defined under the United Nations Convention Against Corruption, or UNCAC) and the unauthorised export of capital.”20 UNCAC’s terms have special relevance to Lebanon’s illegal capital controls regime, given that the convention prohibits embezzlement of private property (Article 22), laundering criminal proceeds (Article 23), and concealment of ownership (Article 24).

Yet Lebanese depositors will need to lobby EU member states extensively to ensure that these coercive measures will be applied. Once the EU Council confirms the structure of its proposed sanctions regime, each EU country will need to implement those sanctions – including, crucially, the intended targets of those sanctions. Therefore, for example, France has shown far more interest in imposing sanctions on Lebanon’s politico-banking elites than Hungary, which has publicly criticised attempts to pressure Lebanese political leaders.21 Extensive lobbying, armed with objective evidence, can persuade more countries both inside Europe and beyond (such as the United States) to construct legal frameworks that impose penalties in line with UNCAC, including asset freezes and seizures (Article 54) and compensation for damages (Article 35).

For its part, the United States has applied individual economic sanctions to specific Lebanese elites, without directly tackling the banking sector. Most notably, in November 2020 the US Treasury imposed sanctions on Gebran Bassil, the prominent Lebanese politician and Hezbollah ally, based on corruption allegations.22 The US Treasury has also sanctioned individuals directly linked to Hezbollah, including financial networks that allegedly fund the group. In late October 2021, three more high-profile Lebanese were hit with sanctions: Jihad al-Arab (an associate of former prime minister Saad Hariri), Dany Khoury (a Bassil associate), and MP Jamil Sayyed. The US sanctions regime bears consequences such as blocking the individual’s US-based assets and prohibiting any transactions with US citizens or companies. To date, however, US authorities have not crafted a sanctions framework like the EU Council’s model, which responds directly to the illegal capital controls regime.

GLOBAL

Know Your Customer (KYC) Regulations:

A creative option for Lebanese depositors would be to pursue foreign banks that have dealt with Lebanese banks under Anti-Money Laundering (AML) and Know Your Customer (KYC) regulations. Already, AML laws have applied enormous pressure to BDL governor Riad Salameh – a key figure in negotiations with Lebanese depositors – who faces criminal prosecution in Switzerland23 and France.24 The same set of AML regulations also require that banks carry out due diligence checks on money transferred from a “high risk jurisdiction.” Banks take procedural steps to confirm that their customers are not engaging in money laundering or other serious financial misconduct. Regulators, particularly in the USA, have issued billions of dollars in fines on banks that have implemented inadequate AML procedures.

Lebanese depositors may have a strong case for breach of AML and KYC regulations – provided that a powerful government regulator agrees to initiate an investigation. Compelling circumstantial evidence exists that correspondent banks may not have carried out enhanced due diligence on Lebanese PEPs who transferred money overseas. Lebanon was a “high risk jurisdiction” prior to October 2019, and has retained that status. Foreign banks would be well aware of the risks of receiving transfers from PEPs since late 2019, particularly given the level of international attention the country has received. Of course, it remains unclear if in fact correspondent banks have done their job and filed suspicious transaction reports related to Lebanese PEPs with the relevant regulators.

Precedent indicates that Lebanese depositors would almost certainly need to rely on a government regulator to investigate and prosecute AML breaches. Private legal cases have not had such success using this route. For instance, in 2021, a US pension fund brought a complaint against Denmark’s Danske Bank, which had been found guilty of laundering $230 million in illicit proceeds through an Estonia branch. The pension fund claimed that the bank had failed to disclose suspicions about money laundering activity in its financial reports, therefore fraudulently inducing the fund to invest in securities. The US court however ruled that a bank is “under no obligation to self-report its growing suspicions” regarding financial misconduct.25 In many jurisdictions, however, banks owe much sterner obligations to government regulators – including compliance with KYC procedures. Accordingly, it would be most prudent to petition a state regulator to initiate an investigation.

It should be noted that establishing serious breaches of AML and KYC regulations could profoundly impact Lebanon’s financial system. If foreign banks received large penalties over transactions with Lebanese PEPs, they would likely consider withdrawing correspondent banking rights from Lebanese banks as a “de-risking” measure. This development would apply enormous pressure to Lebanese banks, which have previously foundered without access to global financial markets. In February 2011, the US Treasury labelled the Lebanese Canadian Bank (LCB) a “prime money laundering concern,” which caused the bank to collapse. In August 2019, Jammal Trust Bank also shuttered its doors after being sanctioned for “brazenly enabling Hezbollah’s financial activities.” This approach does, however, bear serious risks for the nation at large. Wholesale shunning of Lebanon’s financial sector would further damage an already battered economy, while also curbing foreign remittances and transfers of “fresh dollars,” — currently, a lifeline for many Lebanese households.

UN Guiding Principles on Business & Human Rights: Depositors could argue that Lebanese and foreign banks have breached their obligations under the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (the UN Guiding Principles).26 This international instrument imposes a general obligation on governments and businesses to observe their corporate responsibility to respect human rights. Depositors could refer to their entitlements under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which include protections against discrimination and enshrine a person’s right to own property.27 The argument would follow that the illegal capital controls regime has violated those human rights by discriminatorily allowing some account-holders to access their deposits, while denying that right to others. Lebanese banks have likely breached the UN Guiding Principles by implementing illegal capital controls, and foreign banks have done so indirectly by accepting transfers from well-connected depositors.

Unfortunately, little precedent exists for effectively enforcing the UN Guiding Principles, despite their apparent application to Lebanese depositors. Under the convention, a case can be opened through filing a criminal complaint in any jurisdiction. Moreover, law firms can initiate proceedings on behalf of any depositors, with no citizenship requirements involved.

Despite these encouraging features, only rarely has the international community successfully prosecuted corporations under the UN Guiding Principles.

Switzerland, for example, has introduced a National Action Plan for implementing the UN Guiding Principles under Swiss law. The plan requires that the Swiss court system provide judicial remedies for violations committed by Swiss banks. In practice, however, a November 2020 referendum failed to pass the Responsible Business Initiative, which would have made Swiss companies (including banks) directly liable for human rights violations around the world. The proposal’s opponents successfully argued that the law would dissuade global companies from operating in Switzerland, which would harm the Swiss economy.28 Instead, the Swiss parliament has increased due diligence requirements for companies with respect to potential human rights violations. Unfortunately, for now the UN Guiding Principles appear to be more likely to create diplomatic rather than legal pressure on the global financial sector.

OUT OF COURT: BEYOND THE LEGAL SYSTEM

Lebanese depositors have compelling reasons not to rely on foreign litigation to claw back their savings. While assets have been recovered from overseas before, the process usually drains enormous amounts of time and legal fees. For example, prosecutors recovered $4.8 billion stolen by Nigerian president Sani Abacha; yet the trial took 18 years and some of the funds are still not repatriated. Unlike in Nigeria, Lebanese depositors are dealing with an uncooperative domestic government, which further damages their prospects. Successful asset recovery has usually occurred bilaterally, with governments leading the fight to recover funds from other countries. The current Lebanese government, however, has resisted pursuing depositors’ claims – or even negotiating fairly with them. Banking secrecy laws could also frustrate depositors’ ability to gather evidence for trial. For instance, prosecutors recovered less than half the money involved in the Kabul Bank scandal, partly due to difficulty in accessing Afghan bank records.

Some key participants in Lebanon’s illegal capital controls have submitted to voluntary, non-binding undertakings about their commercial dealings. Current shareholders in major Lebanese banks include the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation (IFC),29 the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), and Agence Française de Développement (AFD). Each of these state-backed institutions espouses best practice social objectives in their work. For example, AFD’s mission statement claims that the institution “funds, supports and accelerates the transition to a fairer and more sustainable world.”30 Other corporate shareholders, including US and French banks, claim to follow corporate social responsibility (CSR) pledges, which require business operations to be socially responsible. While not legally binding, these voluntary principles expose both private and public shareholders in Lebanese banks to accusations of hypocrisy for their participation in the illegal capital controls regime.

Many financial partners for Lebanese banks have adopted similar, voluntary obligations covering the social impacts of their commercial dealings. Over time, major global banks have developed corporate frameworks for dealing with financial crime risks, corruption, terrorist financing, and economic sanctions. The most prominent voluntary framework is the Wolfsberg Principles, to which 13 large international financiers have agreed, including France’s Société Générale, a major shareholder in an eponymous Lebanese bank. The Wolfsberg Principles are “a non binding set of best practice guidelines governing the establishment and maintenance of relationships between private bankers and clients.”

Lebanese depositors might allege that Wolfsberg signatories had breached best practice guidelines if they accepted transfers from Lebanon under the illegal capital controls regime. Similar non-legal arguments could apply to most major banks which, even if not signatories to the Wolfsberg Principles, generally advertise CSR policies of their own. Being non- binding, Lebanese depositors cannot seek to enforce obligations under the Wolfsberg Principles or CSR commitments through any court system. Yet these best practice guidelines do expose the trading partners of Lebanese banks to adverse media coverage and allegations of improper corporate conduct.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Lebanese depositors are stuck between a rock and a hard place. Within Lebanon, bankers are being shielded by a recalcitrant judiciary and uncooperative government. In overseas jurisdictions, depositors face challenges related to financial resources and access to evidence. Ideally, claimants would pursue various legal options in tandem with foreign prosecutors and regulators, but this will require those non-Lebanese governments to take an active interest in the issue. What depositors can do, though, is create pressure on Lebanese bankers.

Depositors should lobby foreign governments to provide assistance for various claims under existing laws, especially in countries where Lebanese banks hold significant assets. If one legal case against a single Lebanese bank is successful, it could open Pandora’s box to a barrage of legal action and commercial pressure. Some foreign prosecutors, like the US Department of Justice or the US Treasury, have both the governmental resources and track- record in litigating against financial crimes at home and abroad. Depositors should coordinate lobbying strategies to encourage such governmental departments to pursue Lebanese banks. In addition, non-Lebanese regulators should be encouraged to investigate foreign banking partners for Lebanese banks under laws related to AML and KYC compliance, and the UN Guiding Principles.

Depositors with dual citizenship can supplement government-level prosecution by bringing civil claims against banks overseas. Some legal avenues, such as EU consumer protection laws, offer some promise in terms of generating pressure on Lebanese banks. This much is clear from the fact that banks have already settled some depositors’ claims under consumer protection laws, lest they lose in court and create a precedent for liability to other claimants. The UK High Court has already allowed multiple claims to be heard in British courts. Depositors will need to devise strategies for assisting these litigants to resist intimidation tactics favoured by Lebanese banks, including forced account closures and imbalanced financial resources.

Lobbying efforts should also extend to exhorting foreign governments to impose new forms of legal pressure on Lebanese banks, such as targeted economic sanctions. Countries like the US could follow the EU’s lead in directly targeting the assets of Lebanon’s bankers and politicians, on the basis of serious financial misconduct. As with existing legal avenues, these threats could compel Lebanese bankers to negotiate in good faith with depositors about a fair allocation of the financial sector’s losses.

Activists can also bring non-legal pressure to bear on foreign shareholders in Lebanese banks and overseas financial partners. Strong media and awareness campaigns can demonstrate the hollowness of voluntary, non-binding commitments ostensibly followed by institutions like EBRD and AFD (which own shares in Lebanese banks) and global banks (which act as correspondent banking partners). Media campaigns should emphasise the brutal impact of Lebanon’s illegal capital controls regime on everyday Lebanese depositors, which surely breaches the social impact commitments of these institutions.

A final recommendation is for Lebanese voters to support candidates in the upcoming elections to take depositors’ claims more seriously. Such candidates should commit to policies that encourage transparency and accountability in the financial sector, as well as properly investigating and prosecuting major shareholders in Lebanese banks. Domestically, a National Anti-Corruption Commission must be formed to implement anti- corruption legislation. It is also past time for the Parliament to enact some 60 pending laws, especially those related to good governance and corruption in the public administration, including the law on judicial independence.

EDITOR’S NOTE

Triangle would like to express its gratitude to all of the informants who contributed to this paper including Stefan

Cassella, Chip Poncy, Andrew Feinstein, and John Cassara, as well as several anonymous sources. Special thanks are owed to Jad Ghoussaini for his invaluable research support during the paper’s compilation.

Please note that this report does not purport to offer legal advice. Readers should contact a legal practitioner for advice with respect to any particular matter.