EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Lebanon’s financial sector has long enticed customers with offers of banking secrecy. As in Switzerland, this system has allowed shady characters – both Lebanese and foreign – to stash illicit wealth in Beirut’s vaults. But banking secrecy does something else, just as insidious: it helps destroy Lebanon’s tax potential.

As Lebanon descends into financial collapse, answers to crucial questions lie behind the shroud of banking secrecy – the strict laws that keep account information confidential. Are powerful citizens stashing illicit wealth inside Lebanese banks? Which account holders should take a progressive “haircut” after profiting from Lebanon’s regulated Ponzi scheme? (See the first instalment in this working paper series, “Extend and Pretend: Lebanon’s Financial House of Cards.”)

Banking secrecy also stands in the way of Lebanon achieving fairer, progressive, and more sustainable public finances, capable of reducing public debt and driving investment. Alarmingly, estimates suggest that Lebanon recovers less than half of its potential tax revenue. This situation has come about mainly due to the country’s dismally low top tax rate (20%), and the government’s failure to properly enforce and collect progressive taxes, which citizens pay based on what they can afford.

Alongside the government’s lax attitude to tax compliance, banking secrecy helps many Lebanese submit false tax returns, knowing that the Ministry of Finance cannot directly audit their bank accounts. The state has increasingly turned to more regressive taxes (most notoriously, the proposed WhatsApp tax), which disproportionately burden people with lower incomes. The result is widening inequality and social malaise — both evident drivers of the current protest movement.

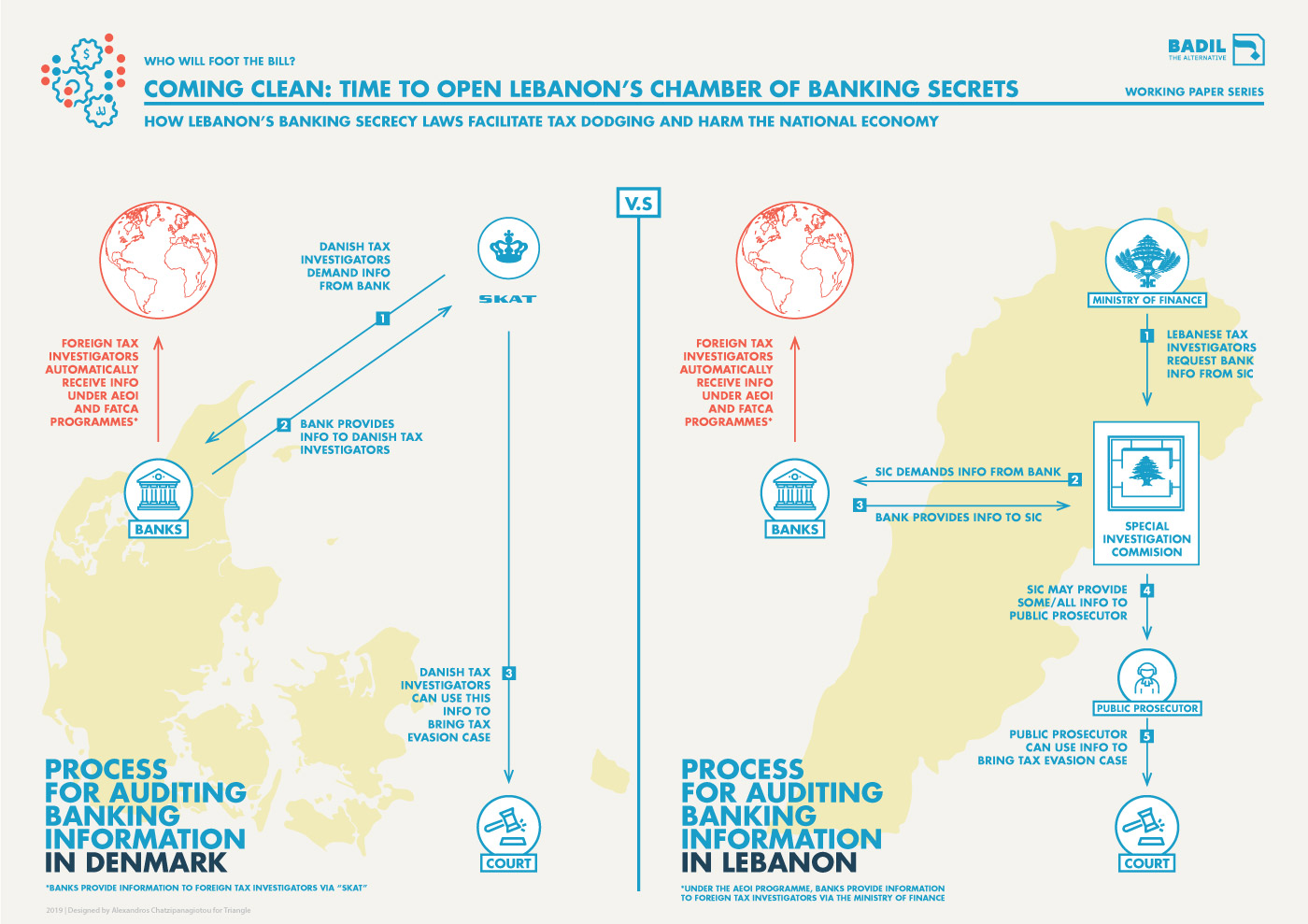

The only road around banking secrecy goes through the Special Investigation Commission (SIC). An unelected body, the SIC can force banks to reveal account information about suspected financial crimes. In reality, the SIC was established at the behest of foreign governments – chiefly, the United States – to combat money laundering. True to those origins, the SIC is far more likely to lift banking secrecy for requests from overseas. By contrast, it hardly ever compels banks to hand over information to the Ministry of Finance, Lebanon’s tax authority.

Due to increased foreign scrutiny, Lebanon has become a less attractive place to covertly stash cash – yet, banking secrecy continues to hobble state revenue. Therefore, the time has come for Lebanon to do away with the practice altogether. But taking down banking secrecy all at once will likely do more harm than good. Secrecy is one of the pillars of Lebanon’s financial sector – removing it immediately would likely result in more capital flight, which is the last thing Lebanon needs at the moment.

Instead, Lebanon should pursue a staged dismantling of the banking secrecy framework. First, confidentiality protections should be lifted for all public officials and civil servants, along with all parties who are awarded state contracts.

Next, the reforms should allow financial investigators to access the accounts of all Lebanese citizens, facilitating stronger compliance with progressive taxes. Then, non-resident account holders should also lose their rights to banking secrecy.

For those final steps to take place, Lebanon’s banks will need to stop relying on what – until recently – were easy wins: providing tax haven services and offering progressively higher interest rates. In other words, Lebanese banks must start working harder for their money, and for the Lebanese economy too. Loans should go to high risk (but more productive) sectors, and small businesses that sustain real jobs and client bases for a healthier, more stable financial industry.

BEIRUT CONFIDENTIAL

During the 1950s, Lebanon fully embraced its identity as a free-wheeling, laissez-faire business hub for the West Asia and North Africa region. The Banking Secrecy Law of September 3rd, 1956 fitted neatly with the zeitgeist of promoting business by reducing government interference – it prohibited bank staff from disclosing to authorities each account’s owner, contents, and other related information.1

The rationale was that customers would view confidentiality as an incentive to deposit funds in Lebanese banks. In turn, these deposits would encourage further investment and bolster confidence in Lebanese bank credit.

The law did attract an impressive inflow of domestic and foreign capital — total deposits increased by 467% between 1950 and 1961.2 This trend continued, even at times of rampant social instability – deposits actually increased during the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990).3

Conversely, banking secrecy’s harmful consequence is that account holders face barely any scrutiny of their financial dealings by global standards (see Box 1). Under the original law, Lebanese banking staff could only disclose account information if the account holder gives written consent, is declared bankrupt, or becomes a party to legal proceedings involving the bank.4

The government seemed to deal with the lack of banking transparency by creating the Special Investigation Commission (SIC) in 2001. But the SIC, Lebanon’s sole body empowered to lift banking secrecy for certain suspected financial crimes, has done virtually nothing to make Lebanese taxpayers more accountable.

BOX 1: Lebanon is ranked 11th in the world on the Financial Secrecy Index 2018, the Tax Justice Network’s (TJN) annual list of banking secrecy jurisdictions. A non-profit organisation, TJN raises awareness about different ways that countries provide financial secrecy. The 2018 rankings place Lebanon – with its powerful confidentiality laws – between well-known tax havens Guernsey (10th) and Panama (12th).

THE SIC: LEBANON’S PAPER TIGER

Established under Law No. 318/2001, the SIC is central to bringing the country’s banking sector into line with international standards of financial transparency.5 The four-person commission – comprised of the BDL Governor, the Banking Control Commission President, a banking judge, and a professional (nominated by the Banque du Liban (BDL) Governor and appointed by the Council of Ministers)6 – is unelected and has deep ties to the banking sector. The original 2001 legislation covered suspected money-laundering offences7 – a priority issue for the United States, one of Lebanon’s key geostrategic allies.

Over time, the SIC’s powers have increased to meet international concerns about other alleged offences. Following the 2007-08 global financial crisis, the United States and several European countries started cracking down on tax havens like Lebanon, which had long allowed citizens to hide wealth and avoid paying tax.8

In response, Law No. 44/2015 empowered the SIC to lift banking secrecy for suspected tax evasion, terrorism financing, narcotics trading, and other finance-related crimes. Theoretically, the new law created a mechanism for better auditing of both Lebanese and non-Lebanese tax compliance.9

In practice, foreign investigators enjoy far more access to banking information than Lebanese government auditors do. Non-Lebanese authorities benefit from automatic data reporting about Lebanese accounts under various agreements between the Ministry of Finance and other countries. Alternatively, foreign governments can bring proceedings to lift banking secrecy through the SIC – a body favourably disposed to cases originating overseas. On average, the SIC granted 77% of foreign requests access to bank information from 2016-18; the SIC approved just 34% of local petitions during the same period.10,11,12 These statistics are consistent with the SIC’s self-declared role as “a platform for international cooperation.”13