Lebanon fits most of the criteria for imposing effective targeted sanctions. The Lebanese state is both politically and economically unstable, which reduces the capacity of elites to operate on a “business-as-usual” basis. Lebanon does not wish to become a pariah state, nor can it afford to become one—its economic recovery, for example, is likely to rely heavily on significant amounts of international aid. It helps further that there are no major trade relations that will impact domestic interests in either country, and that Lebanon’s elites have significant assets abroad.6

The case for imposing sanctions grows stronger when considering the dwindling political capital of Lebanon’s ruling class, which could otherwise render sanctions in- effective. In theory, the Lebanese public or civil society could galvanise defensively behind the state against threatened sanctions. As Lebanese political leaders see their popularity nosedive however, this seems unlikely. Indeed, most Lebanese would likely support sanctions grounded in obstructing the democratic process, under- mining plans approved by the Lebanese government and international community, and serious misconduct of public funds. 7

The EU sanctions being mulled—with their modest ob- jective of forming a government capable of passing economic reforms—are only a first step toward political change in Lebanon. Lest they lead to merely another shuf- fling of cabinet seats, the sanctions must also target the banking sector, which is the true locus of the ruling class’ political and economic clout.

POTENTIAL PITFALLS

While sanctions may be suitable for Lebanon, the EU must be wary of unintended political conse- quences and preventing elites from maintaining functionality through sanctions loopholes. Sanc- tions imply culpability; in Lebanon’s fractious political context, this may influence Lebanon’s political balance. The EUs disinclination to ostra- cise Western “allies” in the broader geopolitical game to counter the influence of Hezbollah and Iran in Lebanon poses a predicament. Western allies arguably bear more responsibility for the economic crisis than Hezbollah, which has less involvement in the banking sector relative to oth- er Lebanese power blocks. At the same time, the EU will be wary of enforcing universal sanctions that allow the strongest groupings—arguably Hezbollah—to gain further relative advantage.

In the context of the 2022 elections, sanctions which label certain individuals as responsible for obstructing government formation and corrup- tion may empower those not sanctioned. There is also fertile ground for political rivals to spin the narratives of blame related to the sanctions and link them to other issues, such as Hezbol- lah’s weapons and/or potential involvement in the August 4th blast.

Finally, targeted persons and entities often cir- cumvent sanctions through shell companies and substitute legal persons whose names are not linked to sanctions.8 In Lebanon, these avoid- ance strategies could function through govern- ment-linked NGOs or political foundations linked to the ruling elite. Most likely though, private companies will be used as fronts by oligarchs to get around sanctions regimes. Lebanon will most likely see increased co-dependency between rul- ing elites and the unsanctioned business commu- nity, potentially with an increase in black market trading of scarce and essential goods, such as fuel and medicine.

BANKS’ CULPABILITY

While the proposed EU sanctions take aim at Leba- non’s venal political class, Lebanon’s banking sector has been a key accomplice in the country’s woes. Most banks—including Lebanon’s central bank, Banque Du Liban (BDL)—are politically connected and played ma- jor roles in Lebanon’s financial collapse. Their actions in managing the fallout also violated the Constitution of Lebanon,9,10 Lebanon’s Code of Money and Credit,11 the Code of Commerce, and the Law of Obligations and Contracts,12 not to mention binding international human rights conventions.13 Yet the Lebanese govern- ment has still not held local banks accountable for these misdeeds; nor has the EU specifically identified key banking figures as targets for foreign sanctions beyond their roles in blocking reforms.

At the same time, Lebanese banks are in a unique posi- tion to enact a fair, transparent, and accountable solu- tion to the economic crisis—and they must be pushed to do so. The banking sector constitutes a simple and effec- tive target for Western sanctions, matching the typical requirement of effective sanctions having clear targets and objectives. Crucially, the targeted elites stand to lose a great deal from sanctions, increasing the likelihood of them taking positive steps towards financial relief.

Indeed, the banking sector faces more a clear-cut threat of legal action than Lebanese politicians do. The strong legal case for prosecuting banks comes from their origi- nal sin of failing to repay money to most Lebanese depos- itors. After the economic crisis began, BDL and commer- cial banks imposed arbitrary and illegal exchange rates on withdrawals of foreign currency.14 At the same time, persons and entities with sufficient connections have been permitted by the same banks to withdraw at least $7 billion in capital.15

Due to the commercial banks’ illegal and informal hair- cut on depositors’ accounts, between October 2019 and March 2021, banks diluted their liabilities to depositors by $31.4 billion, of which an estimated $13.7 billion were in foreign currency deposits paid out at illegal exchange rates.16,17 For its part, BDL has issued several circulars that contravene the Constitution and the Code of Obligations and Contracts.18 By contrast, Lebanese politicians face comparatively loose charges related to obstructing political processes and initiatives.

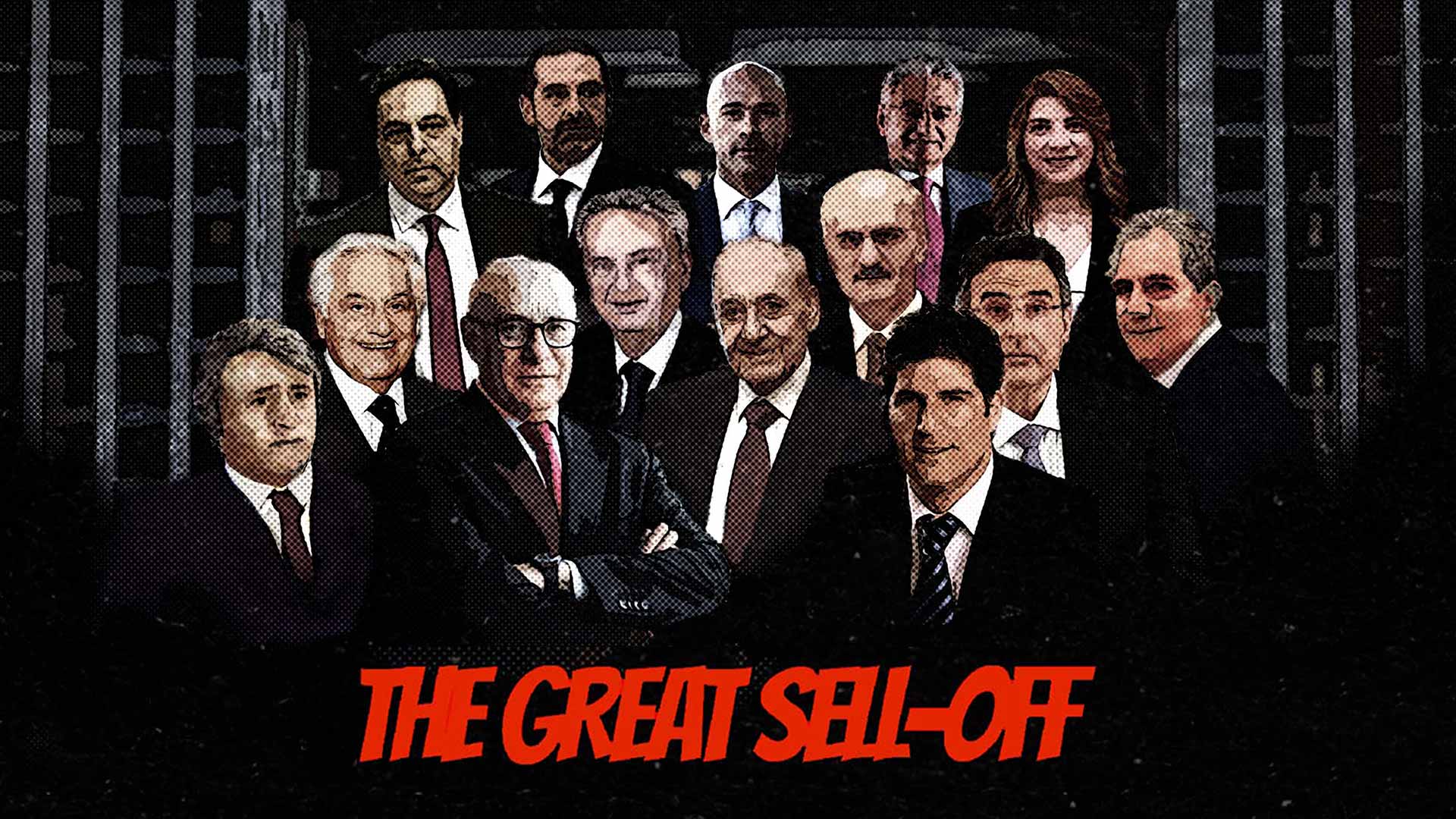

At the same time, sanctioning Lebanon’s banks does not let off the political class. The banking sector has close financial ties with Lebanon’s political elites, who have benefited together from Lebanon’s mismanagement. In 2016, an Economic Research Forum study found that individuals closely linked to political elites controlled 43% of assets in Lebanon’s commercial banking sector and that 18 out of 20 banks have major shareholders linked to political elites. The research also showed that eight families controlled 29% of the banking sector’s assets, together worth more than US$7.3 billion in eq- uity in 2016.19 The family of Saad Hariri featured at the top of this list, with over US$2.5 billion in equity. Fellow billionaire and now PM-designate Najib Mikati, has close ties to Bank Audi (Lebanon’s largest bank by assets) while his brother and business associate Taha Mikati owns a significant stake in Bank Audi through an investment company, Investment & Business Holding.20 It is little wonder that, only a few years ago, 15 out of 20 chairmen at major banks were linked to politicians; six banks employed public officials on their board of management; and almost all boards included former government officials or parliamentarians.21

If influential and politically connected bank shareholders also fear impending sanctions, then the impetus to negoti-ate a fairer share of the financial losses can be increased. Such sanctions would be even more effective if the US and its mighty greenback followed suit. Already the US Depart- ment of Treasury has brought down two Lebanese banks with one move to forbid US correspondent banks to deal with these entities. Thus, the ripple effects of a targeted US sanctions regime on key Lebanese bankers cannot be understated. Moreover, in Lebanon’s case, sanctioning banks and their shareholders will not damage the popu- lation any more than is already being done by the banks’ current limits on withdrawals, exchange rate manipula- tion, and refusal to re-distribute losses equitably.22

AID CHANNELLING

The delivery of humanitarian aid will be an important complementary measure to sanctions, given the increas- ingly desperate needs of Lebanese and refugee popula- tions. Over 75% of Lebanese households are now going short of food23 due to increasing poverty, necessitating an international aid package to provide basic social pro- tections for most of the population. As a “carrot” along- side the “stick” of sanctions, the promise of aid will incen- tivise the political class to stave off a complete collapse in access to basic goods and services.

The prospect of aid, however, also raises the spectre of manipulation. France’s proposed donor conference must consider lessons from both Lebanon and Syria in how aid can be captured and manipulated to support ruling elites, even under sanctions. Encouragingly, aid donors and hu- manitarian agencies have long heeded calls for funding not to flow to or through the government, deeming the public sector an unfit partner for Lebanon’s reform and reconstruction.24 While a morally superior choice, circum- venting the government risks hollowing out the state and entrenching parallel civil society bureaucracies.25 Leba- non’s socio-economic woes are now so widespread that excluding the state apparatus and relying solely on civil society may not be feasible. A balance must be struck that avoids making Lebanon more dependent on aid and stop-gap bureaucracies—specifically in social protection.