EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

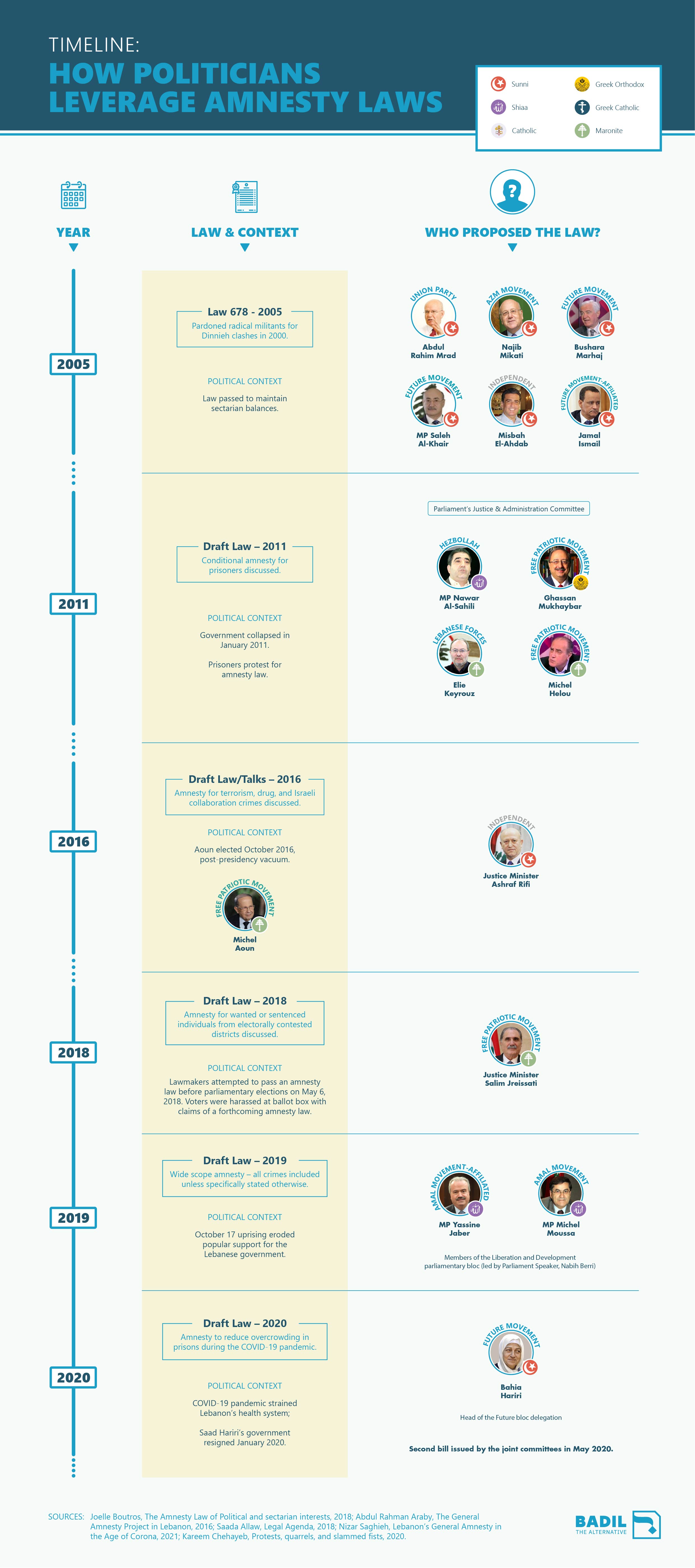

In 1991, Lebanese ruling elites passed a general amnesty law absolving themselves from countless atrocities committed during the country’s civil war. The hasty post-war settlement didn’t just end a decade of conflict; it also shot down the truth and reconciliation process, allowing former warlords to restyle themselves as legitimate political leaders.

Today, thirty years later, the same ruling class continues to use amnesty laws for political leverage. Now, however, they exploit the lives of thousands of unfortunate Lebanese attempting to survive the country’s hellish prison system. The majority of prisoners are not criminal masterminds; they are impoverished men and women who lack political wasta, or influence, to stay out of jail.

With some 10,000 individuals languishing behind bars, canny politicians have learned to propose and debate amnesty laws at critical political junctures in order to leverage the hopes of prisoners, their families, and immediate communities. In a recent example, politicians attempted to rush an amnesty law through parliament after the 2019 October uprising, attempting to appeal to Lebanon’s three major sects: Sunni, Shia, and Christian communities.

Unwilling to lose this powerful political bartering tool, Lebanon’s political elites lack incentive to undertake serious prison reform. It is no wonder, therefore, that Lebanon’s squalid prison cells are the most overcrowded in the region. Poorly maintained buildings and severe overcrowding expose prisoners to countless diseases, and prisoners lack basic essentials such as undergarments, deodorants, and bedding. In times of global pandemic, they can quickly become death traps.

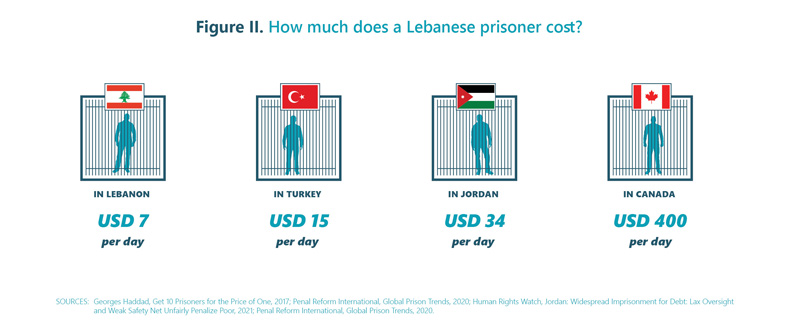

This shameful state of affairs is a symptom of decades of state neglect and paltry investment in the prison system. Without sufficient budgets, the poorly-trained Internal Security Forces, who currently manage Lebanese prisons, are unable to provide prisoners with basic essentials: sufficient healthy food, medical care, clothing, a hygienic environment, not to mention rehabilitation services.

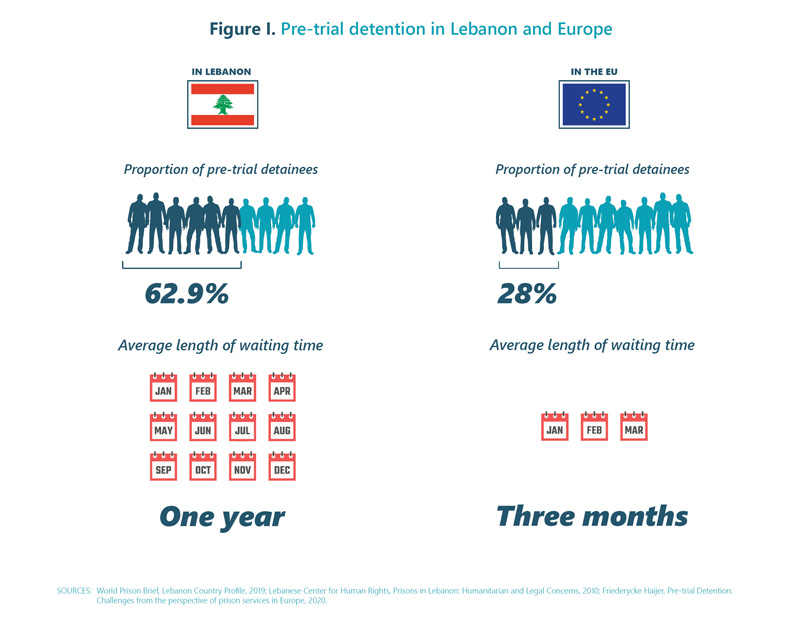

Astonishingly, over half of all Lebanese detainees have not yet received trial. Throughout Lebanon’s recent history, a glut of pre-trial detainees has formed. Thanks to a slow and malfunctioning judiciary combined with laws that permit indefinite pre-trial detention, detainees face an average waiting time of a year just to receive their sentence – four times the average waiting length in Europe.

Nevertheless, several long overdue reforms could bring a modicum of improvement to the country’s shambolic detention regime. Holistic legal reform must arrive first, including the scrapping of arbitrary pre-trial detention periods, providing a legal basis for receiving a timely conviction, regardless of the crime. Soon after, the Ministry of Justice – equipped with sufficient budgetary resources – must finally wrestle prison administration away from the Ministry of Interior.

In the more immediate future, the Ministry of Interior should impose an obligatory training programme for Internal Security Forces (ISF) members who work as prison wardens, in addition to implementing alternative measures to pre-trial detention, such as geographical confinement and reporting to a supervisory office. Ultimately, state policies must concentrate on societal causes of crime by lifting large parts of the population out of poverty. The most important investments must be made in education, jobs, healthcare, and housing. Only these broader steps can ever hope to truly break this vicious cycle and plot a course towards rehabilitation of communities alongside correction facilities.

CROWDING OUT REFORM

Over 10,000 prisoners currently languish in the country’s 25 detention centres which have a collective official capacity of 3,500 inmates, making Lebanon’s prison occupancy level is the highest in the Middle East.[1] Lebanon faces little competition for this unenviable title; Lebanese prison occupancy rates are a shocking 287 percent, some way ahead of the United Arab Emirates (159%) and Jordan (150%).[2],[3]

Box I: Standards, what standards?

Detention conditions in Lebanon fail to meet almost all of the UN’s Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisons, also known as the Nelson Mandela Rules. The Mandela Rules outline 122 key indicators that are used as the primary international standard for evaluating, monitoring, and inspecting prison systems which include guidelines for healthcare, recruitment and training of prison staff, and disciplinary measures.[4] They aim to ensure the protection of prisoners’ human rights and dignity.[5] This set of rules serve as the international standard for the treatment of prisoners and prison management.[6]

Roumieh is the example of overcrowding par excellence; Lebanon’s largest prison holds more than 4,000 inmates alone – a staggering three times its official capacity – in especially squalid conditions.[7] Prisoners in Roumieh do not receive personal products for hygiene, with women prisoners complaining specifically about lacking undergarments, deodorants, and sanitary towels.[8] Poorly maintained buildings expose prisoners to high humidity and inadequate ventilation which, coupled with the severe overcrowding, frequently causes detainees and inmates to develop skin and respiratory diseases.[9] Prisoners rarely experience sunlight and fresh air – a direct violation of Article 60 of Decree 14310 which states that prisoners have the right to access the outdoors for three hours a day.[10] Inmates must lie on the floor without proper bedding in a room originally built to accommodate two prisoners, but in fact holds ten as a consequence of overcrowding.[11]

Overcrowding is no accident. It is a symptom of decades of blatant inaction by the state and paltry investment in the prison system. Only two of Lebanon’s 25 prisons were built for purpose, defying the United Nations Office for Project Services’ Technical Guidance for Building Prisons.[12],[13] The vast majority are renovated buildings, such as Tripoli’s Qobbeh prison which was originally used as horse stables. Lebanon’s two infamous prisons, Roumieh and Zahle Prisons, are the only exceptions to this rule.[14]

However, even Roumieh’s intended layout has been undermined by the fact that prison was opened prior to the completion of the building’s construction. If designated rooms for state security personnel had been included in the prison’s design, these rooms could have served as additional space for prisoners, lessening the impact of by overcrowding.[15] Instead, Lebanese police and security forces have taken over several buildings intended to hold prisoners. Given the lack of investment in prison infrastructure, it is no wonder that the UN has likened the living conditions in Lebanese prisons to “torture.”[16]

SEPARATION ISSUES

A combination of overcrowding and state negligence makes it almost impossible to separate prisoners according to age group, conviction status, and nature of crime. This reality violates not only the Mandela Rules,[17] but also Lebanese Decree 14310 from 1949 (See Box II).[18] Only two prisons (Roumieh and Qobbeh) contain spaces exclusively devoted to hosting minors;[19] however, even in these prisons, many minors are placed in detention with adults due to severe overcrowding, exposing them to sexual assault and violence.[20]

Box II: The weak arm of the law

Decree 14310 from 1949 outlines the organisation of detention centres, including standards for prisons and juvenile reform institutions. The law’s 152 articles deal with a wide array of issues from prison management, inspections, health care, visitation rights, and conditions of prisoners. Many of these provisions are in line with international standards, such as those related to inspection, medical care, separating prisoners according to their sex and criminal record, food, bedding, and clothing.[21] However, poor enforcement means that in many Lebanese prisons, the law’s protections exist merely on paper. Moreover, subsequent laws investing the Ministry of Interior with the authority to run prisons have been similarly overlooked.[22]

In fact, the exigencies of overcrowding mean that prisoners are often separated according to sect, rather than the criteria laid out in Lebanese law.[23] For example, Sunni prisoners are and those accused of violent extremism are generally sent to Roumieh’s Block B, while Shiite prisoners are allocated Block D.[24],[25] By doing so, prison managers hope to prevent inter-sectarian tensions within the prison;[26],[27] but in reality, this practice overrides the separation of prisoners based on other important characteristics mentioned above, at the expense of vulnerable minorities (See Box III).

BOX III: Transgender and prison separation

Article 9 of Decree 14310, stipulating that females must be placed in prisons separate from men, is one of the few separation requirements respected in Lebanese prisons.[28] However, the Lebanese law recognises only the gender indicated on legal identification, and not according to an individual’s choice. If transgender individual fails to change their sexuality on their legal identification, they would be imprisoned according to the sex stated on their identification.[29] This violates Rule 7 of the Mandela Rules which states that once an individual is admitted into prison, information regarding their unique identity must be collected and their perceived gender must be respected.[30]

THE LONG WAIT

Throughout Lebanon’s history, laws that permit indefinite pre-trial detention combined with a slow and malfunctioning judiciary has created a glut of pre-trial detainees – prisoners who have not yet been convicted of any crime. Of Lebanon’s 10,032 inmates, 6,307 are currently awaiting trial, creating a pre-trial detention rate of 62.9%, over double the average in Europe (25-28%).[31],[32]

In some cases, interminable pre-trial detention is not only inhumane – it is illegal too. Article 108 of the Code of Criminal Procedure provides maximum pre-trial detention lengths according to the nature of the crime. The period of pre-trial detention for a misdemeanour – legally defined as a crime with a penalty ranging from 10 days to 3 years – cannot exceed two months. [33],[34] Those accused of felonies – crimes with a penalty ranging from three years of hard labour and a death sentence[35] – should only wait six months before their trial.[36]