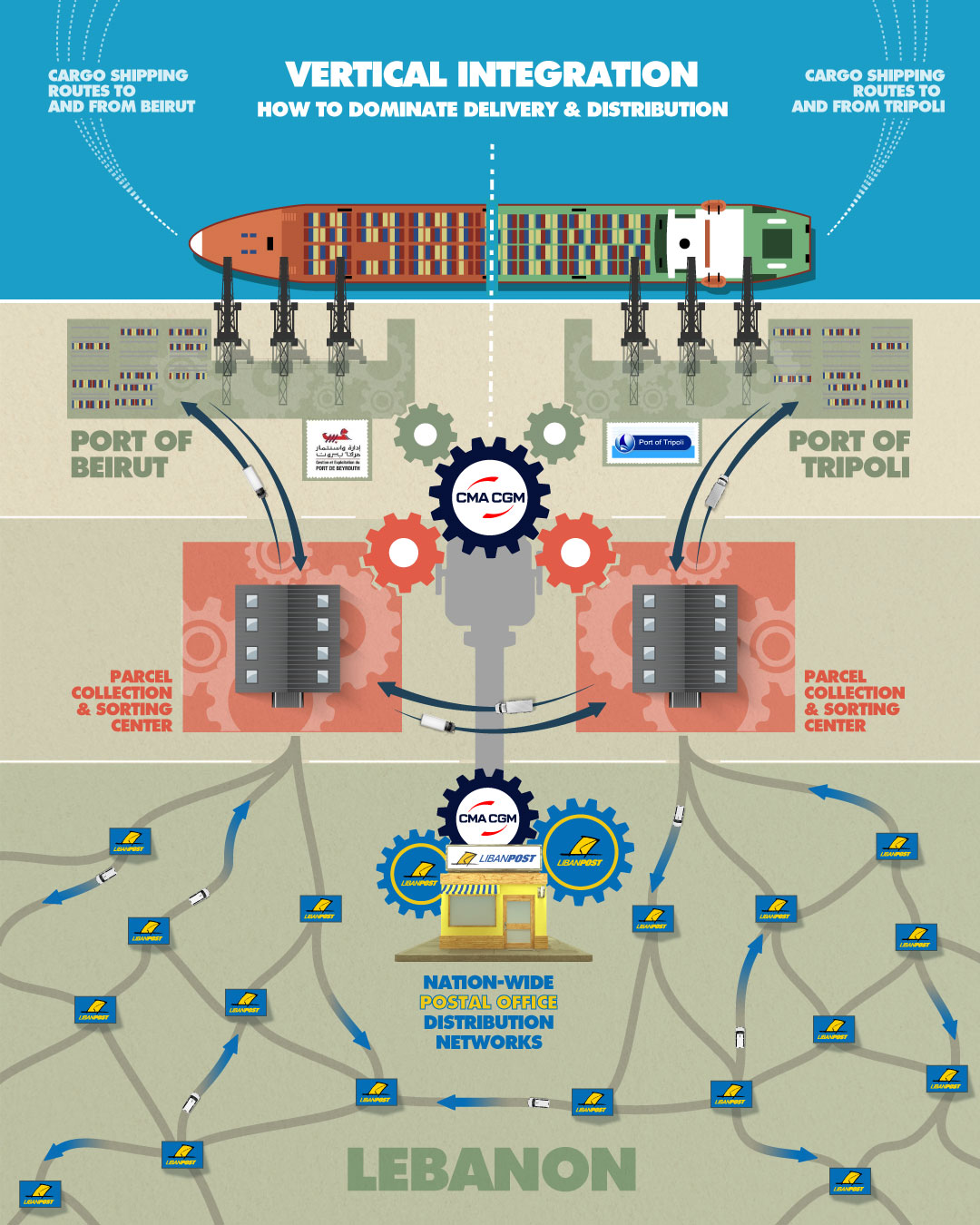

Shipping companies that can combine and effectively manage shipping, port terminals, and inland transport and logistics can secure a significant cost advantage over their competitors, according to Wayne K. Talley, in his book Port Economics.63

This ‘vertical integration’ between international supply chains and local distribution networks asserts control over the entire delivery process.64 Lee added this would help Saadé secure his business by blocking competitors and ensuring that “all e-commerce getting into Lebanon is for LibanPost. No one else could touch it.”

The Post Office as an Alternative to Zombie Banks

The postal carrier’s legal leeway to expand into banking services is another prime opportunity, especially given the current dearth of competition in the market. Since 2019, Lebanese banks have ceased to perform basic banking operations and have trouble even safely opening branches due to the risk of raids by angry depositors. Indeed, they have become textbook examples of ‘zombie banks’, which the International Monetary Fund (IMF) defines as chronically under-capitalized banks that do not receive the necessary remedial treatment from owners or regulators, and are “no more than cash stores that provide money printed by the central bank”65

Depositor groups and the IMF have called for banks to be held liable for tens of billions of dollars in losses, while the Association of Banks in Lebanon has demanded that the government fix the gaping hole in their balance sheets and repay the banks for decades of government loans. Efforts to reform and restart the sector have thus stalled, with vested banking interests among the political class derailing any serious legislative efforts that would see the bank owners and managers incur losses.66 With banks effectively removed from Lebanon’s economic cycle, financial flows have migrated massively to the informal, cash economy.67 In 2022, cash transactions accounted for 45.7 percent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), marking a 74.4 percent increase from 2021, according to the World Bank.68

The obvious market demand for formal financial services has led to a scramble for alternatives and a burgeoning sector for e-commerce companies.69 The 65-year-old law allowing the postal sector to provide financial services has thus also come under renewed focus as a means to restart banking services in the country, even while the commercial banks themselves remain paralyzed. El-Corm, the caretaker minister of telecommunications, pointed to this dynamic in a recent interview with Badil.

“Lebanon is going through troubled times as far as the banking sector is concerned today; a lot of companies are mushrooming that are dealing with payment collections and these types of basic services,” he said. “The future of the postal sector might be financial services.”

Such an arrangement has international precedent. National postal carriers in France, Italy, Switzerland, and New Zealand all include financial services within their mandates.70 LibanPost is also ideally positioned for such a development as a trusted brand with established customer relations and 94 post offices throughout the country—almost double the 57 branches Bank Audi, Lebanon’s largest commercial bank, had as of September 2023.71

“You could imagine in a country where there is effectively no functioning banking system, that it would be a real opportunity to say: “Look, we can establish it through LibanPost”, said Lee, the postal policy specialist.

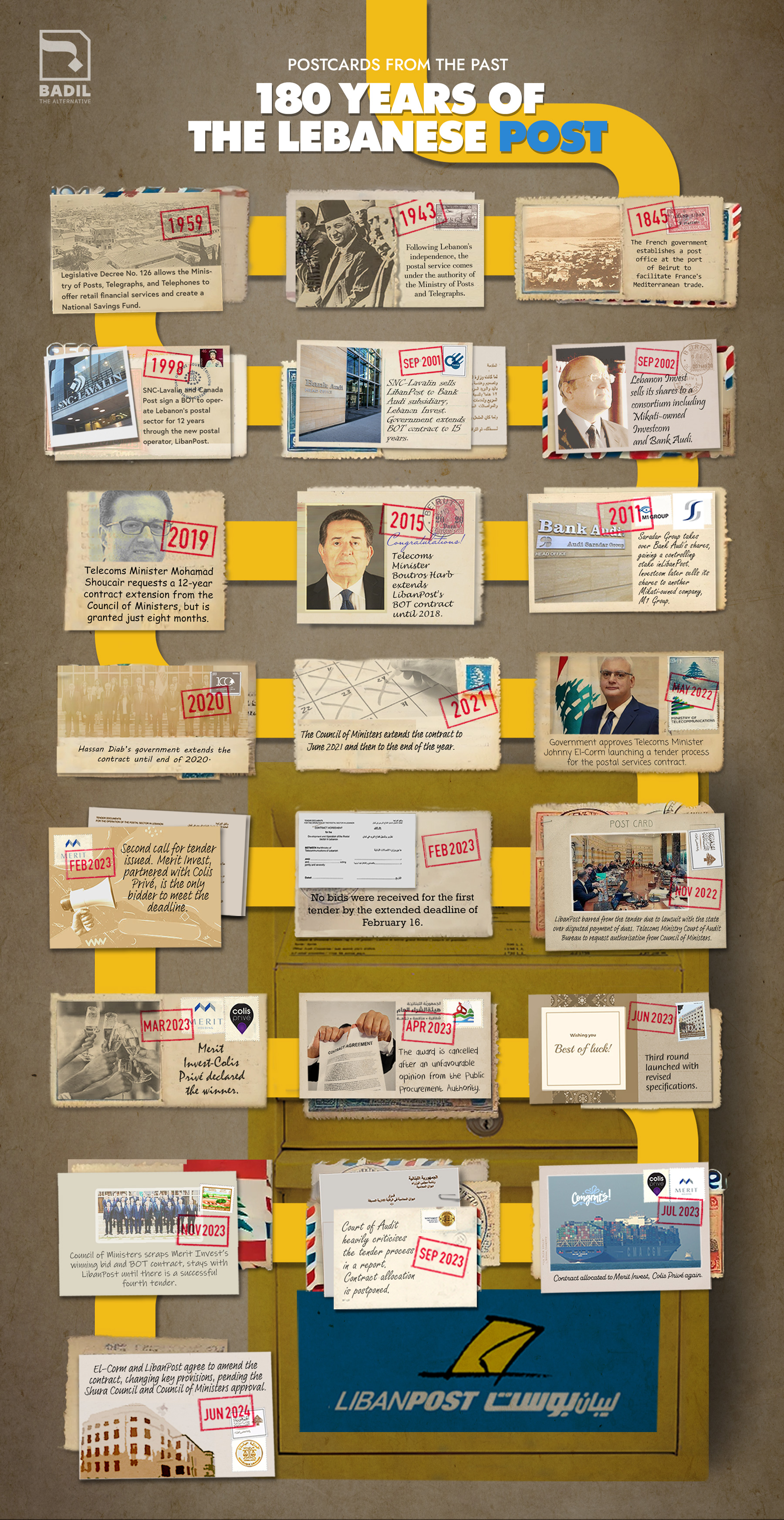

3rd Tender Attempt: Minister Fails Again to Force it Through

Pushing past the failure of the first two tender attempts for a new postal operator, the Ministry of Telecommunications launched a third tender round in June 2023. This time, the ministry amended the terms to define the state’s portion of revenues as a percentage of each of the services the operator would offer and added a feasibility study, as per the PPA recommendations.72 Contrary to PPA recommendations, however, El-Corm allowed prospective companies only five weeks to prepare their bids based on the new tender terms. Three companies—Ghana Post, DHL-affiliated Trust Trading, and Egypt Post—protested the ministry’s deadline as being too short, but they were effectively ignored.73

Merit Invest and Colis Privé thus once again came out as the only bidder and were declared the winner. Their submission included bold revenue projections for LibanPost, anticipating a 476 percent net income increase over the next nine years,74 while offering to pay 12 percent of annual revenues to the state.75 On August 3, 2023 El-Corm submitted a request to the Council of Ministers for authorization to approve the bid.

In September, however, the Court of Audit, a body mandated to oversee public spending, rescinded the Saadé concession. While Merit Invest’s proposal promised increased state revenue, the Court of Audit report identified serious faults in the holding company’s contract and the ministry’s management of the tender process. The Court’s document included a table illustrating that the new revenue-sharing scheme under the Merit Invest and Colis Privé bid would, in application, result in a revenue loss for the state of $US5 million over a nine-year period.76

The Court also chastised the ministry for setting narrow tender requirements that seemingly favored Merit Invest and Colis Privé. This included implementing overly short tender application windows that prevented competitors from submitting bids.

“Submitting a serious offer requires a much longer time than the advertisement period, especially since the entities that are expected to have the required qualifications are mostly foreign entities (…), and by nature need a longer time to get to know the Lebanese reality related to the deal”, stated the report.77

The report noted that “the short period constituted a privilege for the bidding party as long as it seemed to be the only one – or one of the few parties – that had a long time to learn about the Lebanese reality, by virtue of submitting a previous offer in the same deal.”78

Beyond this, the Court questioned Colis Privé’s qualifications, pointing to its lack of experience in post office management. To date, its operations have been focused on parcel delivery. The Court made clear that it found Merit Invest a highly dubious candidate for the Ministry to back so avidly.79

Through the autumn of 2023, the telecommunications minister, the Council of Ministers, the Court of Audit, and the PPA held heated meetings.80El-Corm’s attempts to push the cabinet to overturn the Court of Audit came to naught, however, as the cabinet followed through on the court’s decision to cancel the contract with Merit Invest and Colis Privé. The Council of Ministers then ruled that LibanPost’s contract should be extended until a new operator is found through a successful tender process – which has not been announced as of this writing.

The Council of Ministers also ruled that the current LibanPost contract should be amended. Changes under discussion reportedly include the company paying 12 percent of revenues to the state on all services, offering a 15 percent discount on postal services within the government, and amending tariffs currently based on the former exchange rate of LL 1,500 per $US1.81 LibanPost’s rent for the sorting centers at the Beirut International Airport and Riad Al-Solh Center are also slated to increase to $US1.4 million. As of this writing, however, these contract amendments remain unimplemented.

The telecoms minister has gone public with his frustrations, telling Lebanese newspaper Nida Al-Watan that the Court of Audit’s recission of Merit Invest-Colis Privé’s contract was an attempt by “certain parties” to “destroy” the postal services sector and to hand it “for free” to Wissam Achour.82

Notably, Judge Mohammad Badran, who leads Lebanon’s Court of Audit and suspended the concession to Merit Invest and Colis Privé, was appointed by Parliamentary Speaker Nabih Berri.83 The former head of the Court of Audit, Aouni Ramadan, is now a close advisor to Berri.84

The caretaker telecommunications ministry has informed Badil that the fourth tender process is in its early stages. Yet, it remains far from clear when it will launch or if it will finally allow for a new postal sector operator to be selected in a fair and transparent manner.

Looking Ahead

The Mailbag Stays Full of Vested Interests

When the Ministry of Justice brought counterclaims against LibanPost before the Shura Council in early 2023, the Caretaker Prime Minister Mikati publicly called on the Financial Prosecutor, Judge Ali Ibrahim, to investigate LibanPost for any potential financial misdealings.85 This request now appears to have been largely performative. No results have been announced in over a year since the Prime Minister’s request, and speaking with Badil, the telecommunications minister said he was unaware of any ongoing investigations.

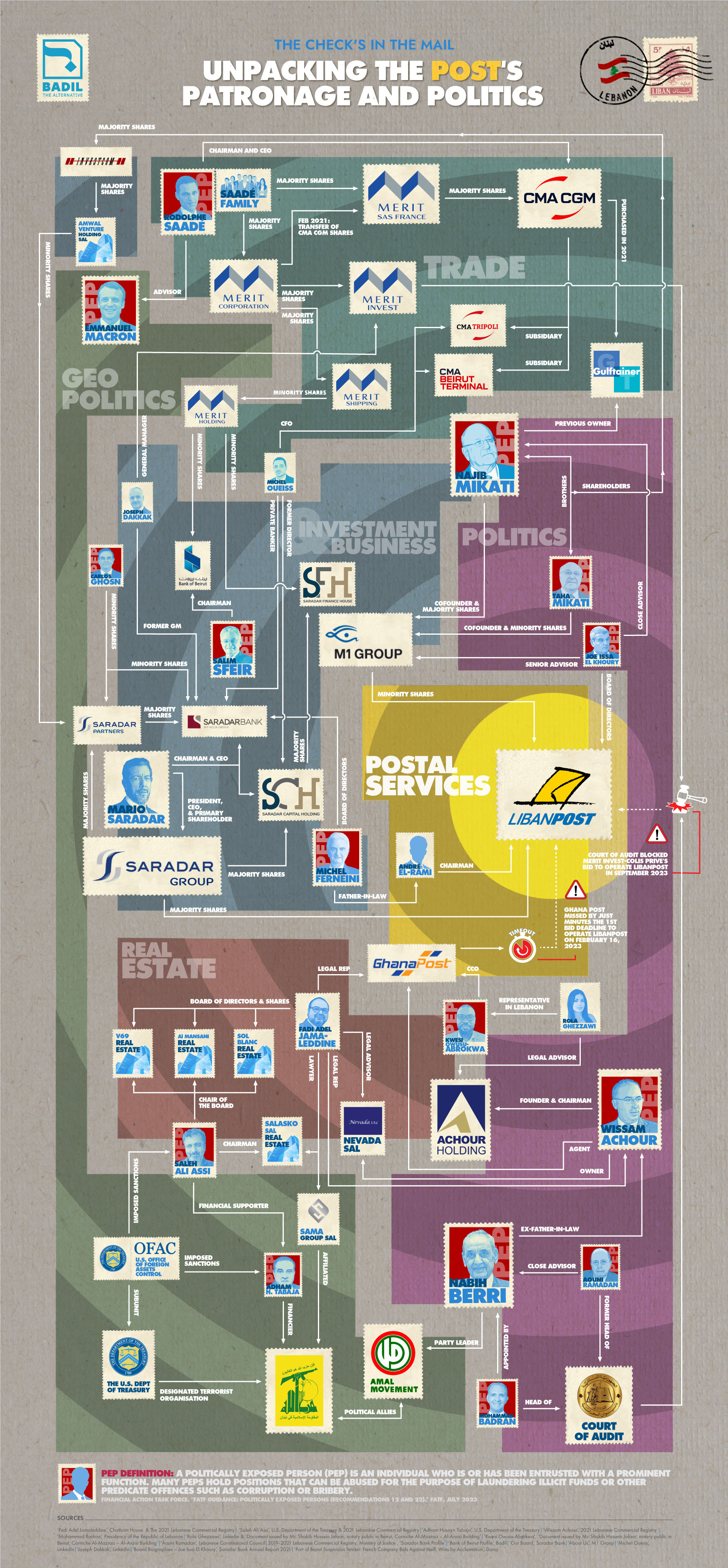

In the meantime, a tangled web of financial and political interests continues to surround the postal service, revolving between Prime Minister Mikati, Rodolphe Saadé, and Mario Saradar. For instance, the Saradar Group continues to hold 70 percent of LibanPost, as of 2021, the last year the Lebanese Commercial Registry was publicly available online. The registry also showed that, through a series of holding companies, the Mikati family holds significant shares in Saradar Partners, a subsidiary of Saradar Group.86

The interests of these shareholders continue to be represented on LibanPost’s board. Today, one of LibanPost’s board members, Joe Issa El Khoury, is a senior advisor at Mikati’s M1 Group, former CEO of M1’s investment branch, and a close advisor to the prime minister. El Khoury also previously served as a board member of Saradar Bank.87 Similarly, LibanPost’s chairman and general manager, Andre El-Rami, is the son-in-law of Michel Ferneini, a Saradar Bank board member. Ferneini was reportedly close to the ex-Banque du Liban governor Riad Salameh, who was sanctioned by the US in August 2023.88

That CMA CGM acquired Tripoli Port from Mikati as a private businessman, and then Mikati as prime minister bestowed upon CMA CGM the contract for the Beirut port, at the very least hints at a special relationship between Saadé and Mikati. Notably, in tandem with Mikati’s return to premiership in 2021 under French auspices, CMA CGM’s workforce in Lebanon increased massively, from 250 in 2019 to more than 2,000 in 2023.89

Meanwhile, Merit Holding has shares in Saradar Financial House, another holding company in the Saradar network. The current chief financial officer for CMA CGM’s Beirut and Tripoli port operations, Michel Oueiss, was previously Director of Saradar Capital Holding, the holding company for Saradar Bank, and before that, a private banker at Saradar Bank. Other shared senior staff include the general manager of Merit Invest until June 2023, Joesph Dakkak, who was previously General Manager of Saradar Bank and was awarded the French presidential Order of Merit while in office.90

Why the Lebanese Should be ‘Going Postal’

Among all the interests enriching themselves in the orbit of the postal service, the Lebanese state and the citizens it is meant to serve have been absent. For 25 years, Lebanon’s kleptocratic elites have corralled this public service for their own ends and used it as a reliable siphon to divert public revenues into their own pockets. The telecommunications minister seemed to indicate an awareness of such in his recent interview with Badil.

“I have concerns overall about the renewals of the agreements [with LibanPost], how they were done, and for what purpose” said El-Corm. “The end result was not in favor of the government.”

And yet, in the tenders he has attempted in recent years, by changing the nature of the contract from a BOT to a management agreement, he is essentially formalizing the de facto privatization of the postal service that has been in effect for more than two decades. Instead of righting the historic wrong that has shortchanged the public purse, the minister appears to have found a backdoor through which to cement it in perpetuity, all the while dodging niftily the uproar and pushback that normally attends attempts to privatize state assets. This is particularly relevant in the context of the ongoing financial crisis, during which a central tenet of the banking elite has been that state assets should be privatized to cover their losses – a suggestion vehemently opposed by depositors’ groups and the broader public.

El-Corm asserted to Badil that the management contract was necessary because “the ministry is not capable of handling this task themselves.” In other words, a transfer was not possible in the ministry’s present financial circumstances.

This argument – that the government must farm out control of a service to the private sector because it is incapable of delivering the service itself – is not implausible. However, it also mirrors El-Corm’s stance earlier this year regarding the state-owned mobile telecommunications companies ‘Alfa’ and ‘Touch’—formally Mobile Interim Company 1 (Alfa) and Mobile Interim Company 2 (Touch)—entering the burgeoning e-commerce sector.91 The telecommunications carriers’ existing customer base, covering almost the entire population, ideally situates them as major players in what is virtually certain to be a highly profitable business, given the unmet demand for financial services created by the now-defunct commercial banking sector. El-Corm, however, has pushed for these state-owned companies to sub-contract this revenue-generating service to the private sector – a curious move for a government desperate to increase revenues, and one that has garnered criticism from experts and reform-oriented politicians alike.92

What makes the notion that the state doesn’t have the capacity to run such services is that, unlike almost every other public sector entity, postal and telecommunications sectors are profitable, meaning they would be a net benefit to the ministry’s balance sheet, rather than a burden. Being able to pay for their own operations and capital investments means that they are also financially equipped to recruit the necessary human resources to offer the service in-house. What seems to be missing is not the “capability”, as the minister put it, but rather a concern for the public good and a willingness to curtail elite earnings.

That the minister is attempting to leverage the government’s wider financial distress to justify selling to the private sector revenue streams that are rightly the state’s is an appalling betrayal of public trust. Indeed, the entire fiasco around the LibanPost tender again shows that even as the average Lebanese citizen struggles to survive the country’s economic collapse, Lebanon’s political and financial elite, who orchestrated the collapse through their wanton recklessness and elite capture, remain unabashedly determined to continue plundering.

Merit Invest and Ghana Post declined repeated requests for comment. LibanPost, Saradar Bank, and Achour Holding did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Badil would like to thank the many journalists, researchers, supporters, and activists who have helped compile this investigation. Special thanks go to: Adam Chamseddine, Alexandros Chatzipanagiotou, Spencer Osberg, Michael Huijer, Perla Daou, Benjamin Fève, Nancy Ehrenberg-Peters, Nizar Ghanem, Sami Halabi, and the many others who made this investigation possible.

Correction:

A previous version of this article attributed the operation of a container terminal in Ashdod, Israel to CMA CGM. The attribution was made according to an online source on CMA CGM’s site which has since been taken down. Badil’s editorial team regrets any inaccuracy that may have occurred.

ENDNOTES & REFERENCES

- May Makarem, “Soixante-dix ans d’histoire postale française à Beyrouth”, L’Orient-Le Jour (2 December 2009), accessed: https://www.lorientlejour.com/article/639550/Soixante-dix_ans_d%2527histoire_postale_francaise_a_Beyrouth_.html

- Semaan Bassil, Mail in the Levant: Beirut. A Case Study in the Early Age of Steamship & Globalization (1835-1914) (Cedarstamps, 2023), 42.

- Universal Postal Union, “Member Countries”, accessed at: https://www.upu.int/en/universal-postal-union/about-upu/member-countries?csid=-1&cid=175#mb–1

- Parliament of Lebanon, “Legislative Decree No. 126 from June 12, 1959.”

- Ibid.

- Maya Sioufi, “More than just your mailman”, Executive Magazine (8 May 2013), accessed at: https://www.executive-magazine.com/business/libanpost-lebanon-growth-strategy

- Elie Ferzli, عاماً من سيادة “ليبان بوست”: الدولة في خدمة شركة 20”“, Legal Agenda (15 November 2021), accessed: https://legal-agenda.com/20-عاماً-من-سيادة-ليبان-بوست-الدولة-في-خ/ ; “CPI Inflation Calculator”, accessed: https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl?cost1=5%2C500%2C000.00&year1=199712&year2=202406

- Ferzli, عاماً من سيادة “ليبان بوست”: الدولة في خدمة شركة 20” “, Legal Agenda.

- Sioufi, “More than just your mailman”, Executive Magazine.

- “Bank Audi”, Badil, accessed: https://thebadil.com/bank-profiles/bank-audi/

- Caretaker Minister of Telecommunications, Johnny El-Corm, in an interview with Badil [25 April 2024]

- Elie Ferzli, ”بعد 25 عاماً من السيطرة على القطاع: هل تُقصى “ليبان بوست” عن مزايدة البريد؟,“, Legal Agenda (11 November 2022), accessed: https://legal-agenda.com/بعد-25-عاماً-من-السيطرة-على-القطاع-هل-تُق/

- Ferzli, “عاماً من سيادة “ليبان بوست”: الدولة في خدمة شركة 20”, Legal Agenda.

- Elie Ferzli, “وزير الاتصالات يتغاضى عن النزاع القضائي مع “ليبان بوست”: إبراء الذمّة في يد الحكومة”, Legal Agenda (24 November 2022), accessed: https://legal-agenda.com/وزير-الاتصالات-يتغاضى-عن-النزاع-القضا/

- H. Rammal, “The Impact of Merger and Acquisition Activities on the Efficiency of Banks: The Case of Lebanon” Staffordshire University (2020), https://eprints.staffs.ac.uk/6894/2/Final%20Thesis%20-%20Batoul.pdf, p. 105 ; “Bank Audi”, Family Business Histories , accessed: https://www.familybusinesshistories.org/spotlights/bank-audi/

- Sioufi, “More than just your mail man”, Executive Magazine.

- “Liban Post: L’analyse Stratégique.” Institut de Prospective Economique du Monde Méditerranéen (IPEMED), (January 2015), accessed: https://www.ipemed.coop/adminIpemed/media/fich_article/1458116868_ipemed—liban-post.pdf, 5.

- Ferzliبعد 25 عاماً من السيطرة على القطاع: هل تُقصى “ليبان بوست” عن مزايدة البريد؟”,”, Legal Agenda.

- Ibid.

- Mohamad Farida, ”Don’t Let It Burn: Lebanon’s Last Chance For A Progressive Deposit Recovery Plan”, Badil, (1 December 2023), accessed: https://thebadil.com/policy/policy-papers/progressive-deposit-recovery-plan/

- Ferzliبعد 25 عاماً من السيطرة على القطاع: هل تُقصى “ليبان بوست” عن مزايدة البريد؟”,”, Legal Agenda.

- Ferzli, “وزير الاتصالات يتغاضى عن النزاع القضائي مع “ليبان بوست”: إبراء الذمّة في يد الحكومة”, Legal Agenda.

- Ferzliبعد 25 عاماً من السيطرة على القطاع: هل تُقصى ليبان بوست” عن مزايدة البريد؟”,”, Legal Agenda.

- Interview with El-Corm, 25 April 2024.

- Elie Ferzli, الحكومة تواجه القضاء… والقانون: لا بديل عن “ليبان بوست” ”, Legal Agenda (13 December 2022), accessed: https://legal-agenda.com/الحكومة-تواجه-القضاء-والقانون-لا-بد/

- Elie Ferzli, مزايدة البريد تفشل… ووزارة الاتصالات ترفض استرداد القطاع””, Legal Agenda (17 February 2023), accessed: https://legal-agenda.com/مزايدة-البريد-تفشل-ووزارة-الاتصالات/

- Philippe Hage Boutros, ”CMA CGM s’allie avec La Poste pour succéder à LibanPost”, L’Orient Le Jour, (12 July 2023), accessed: https://www.lorientlejour.com/article/1343188/cma-cgm-sallie-avec-la-poste-pour-succeder-a-libanpost.html

- Ghana Post, accessed: https://ghanapost.com.gh/

- Ferzli, “”مزايدة البريد تفشل… ووزارة الاتصالات ترفض استرداد القطاع, Legal Agenda.

- Ibid.

- “Lancaster Accra”, accessed: https://lancasteraccra.com/

- Scott Preston, ”The untouchable hotel”, Executive Magazine (16 April, 2018), accessed: https://www.executive-magazine.com/real-estate-2/the-untouchable-hotel

- Rula Ibrahim, “”ثلاثي عاشور ــ البلدية ــ المحافظ يحاصر بيروت بالمجارير Al-Akbar (17 November 2018), accessed: https://al-akhbar.com/Community/261869

- “سند توکیل:” The document conferring upon Rola Ghezzawi and Amir Fadel Wehbe the authority to legally represent Ghana Post’s Chief Commercial Officer, Kwesi Owusu-Abrokwa, in Lebanon states: “A power of attorney document registered with the Notary Public in Ghana on 13/01/2023 and duly and finally certified by the Lebanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs No. 13051, dated 2/02/2023. It was reviewed and signed before me, I, Shakib Jafaar, a licensed notary public in Beirut, after reciting this document, consisting of two pages bound with a seal, and signing it publicly in the English language he is fluent in. He agreed to its content of his own free will and was ratified on Friday, the seventeenth of February, in the year two thousand twenty-three, the Notary Public in Beirut, Shakib Jafaar.”

- Rola Ghezzawi, LinkedIn profile, n.d., https://www.linkedin.com/in/rola-ghezzawi-650009196/?original_referer=https%3A%2F%2Flb%2Elinkedin%2Ecom%2F&originalSubdomain=lb

- ”About us”, Achour Holding, accessed: https://achourholding.com/

- Rola Ghezzawi, LinkedIn profile, n.d., https://www.linkedin.com/in/rola-ghezzawi-650009196/?original_referer=https%3A%2F%2Flb%2Elinkedin%2Ecom%2F&originalSubdomain=lb

- Rola Ghezzawi, LinkedIn post, n.d., https://www.linkedin.com/posts/rola-ghezzawi-650009196_قرار-التلزيم-المؤقت-activity-7059526082546253827-D0kp/

- ” بيان توضيحي لوكيل عاشور وشركة غانا بوست عن مزايدة البريد“, National News Agency (2 November 2023), accessed: https://www.nna-leb.gov.lb/ar/متفرقات/652025/بيان-توضيحي-لوكيل-عاشور-وشركة-غانا-بوست-عن-مزايدة

- ”About us”, Mena City Lawyers, accessed: https://www.menacitylawyers.com/

- Lina Khatib, ”How Hezbollah holds sway over the Lebanese state”, Chatham House (June 2021), accessed: https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/2021-06/2021-06-30-how-hezbollah-holds-sway-over-the-lebanese-state-khatib.pdf,

- Republic of Lebanon Ministry of Justice Commercial Register (2021), ’Sol Blanc’; ’Al Mansouri Real Estate’; ’V69 Real Estate’

- “Treasury Designates Prominent Lebanon and DRC-Based Hizballah Money Launderers”, S. Department of Treasury (13 December 2019), accessed: https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm856

- Elie Ferzliهيئة الشّراء العامّ تفضح تلزيم البريد: العرض غير مطابق للشروط”,“, Legal Agenda (7 April 2023), accessed: https://legal-agenda.com/هيئة-الشّراء-العامّ-تفضح-تلزيم-البريد/

- ”Report No. 2 issued on the April 6, 2023”, Public Procurement Authority; Elie Ferzli, “هيئة الشّراء العامّ تفضح تلزيم البريد: العرض غير مطابق للشروط”,” Legal Agenda (7 April 2023), accessed: https://legal-agenda.com/هيئة-الشّراء-العامّ-تفضح-تلزيم-البريد/

- Chris Bryant, ”Shipping’s $500 Billion Profit Can Take on Amazon“, Bloomberg (2 May 2022), accessed: https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2022-05-23/shipping-s-500-billion-profit-can-take-on-amazon

- Jasmin Lilian Diab, ”Meet The Lebanese Named Commander Of The French Legion Of Honor“, 961 (5 December 2019), accessed: https://www.the961.com/lebanese-saade-commander-french-legion-of-honor/

- Leila Abboud and Sarah White, ”Rodolphe Saadé, shipping boss who sailed into France’s business elite“, The Financial Times (24 April 2024), accessed: https://www.ft.com/content/c42b5588-7f72-407b-b5b0-6fa6599e34a2 ; “Bloomberg Billionaires Index“, Bloomberg, accessed: https://www.bloomberg.com/billionaires/

- “A Humanitarian Ship for Lebanon”: Emmanuel Macron praises the commitment of French companies, NGOs and public institutions taking part in the CMA CGM Foundation’s initiative“, Executive Magazine (1 September 2020), accessed: https://executive-bulletin.com/slider/a-humanitarian-ship-for-lebanon-emmanuel-macron-praises-the-commitment-of-french-companies-ngos-and-public-institutions-taking-part-in-the-cma-cgm-foundations-initiative

- “CMA CGM Group announces the acquisition of Tripoli Container Terminal’s Gulftainer Lebanon“, CMA-CGM (2 March 2021), accessed: https://www.cmacgm-group.com/en/news-media/cma-cgm-group-announces-the-acquisition-of-tripoli-container-terminal-s-gulftainer-lebanon

- “CMA CGM reopens its Lebanon Headquarters and reiterates its determination to pursue its development in the country“, CMA-CGM (11 November 2021), accessed: https://www.cma-cgm.com/local/lebanon/news/52/cma-cgm-reopens-its-lebanon-headquarters-and-reiterates-its-determination-to-pursue-its-development-in-the-country-br-br-

- “Mikati launches ”Masterplan for Beirut Port”: We Seek Rendering It as an Attraction for Optimal Investors”, National News Agency (11 February 2022), accessed: https://www.nna-leb.gov.lb/en/economy/521479/mikati-launches-master-plan-for-beirut-port-we-see

- Alex Ray, “Business As Usual: Long Standing Corruption Threatens Beirut’s Port Reconstruction”, Badil (4 April 2022) accessed: https://thebadil.com/investigations/business-as-usual-long-standing-corruption-threatens-beiruts-port-reconstruction/#_edn11

- “CMA CGM Group announces the acquisition of Tripoli Container Terminal’s Gulftainer Lebanon”, CMA-CGM (2 March 2021) accessed: https://daraj.media/en/port-of-beirut-suspicious-tender-french-company-bids-against-itself-wins-by-acclamation/ https://www.cma-cgm.com/local/lebanon/news/50/cma-cgm-group-announces-the-acquisition-of-tripoli-container-terminal-s-gulftainer-lebanon; Issamar Lteif, Jamil Saleh, et al., “Port of Beirut Suspicious Tender: French Company Bids Against Itself, Wins by Acclamation“, Daraj accessed: https://daraj.media/en/port-of-beirut-suspicious-tender-french-company-bids-against-itself-wins-by-acclamation/

- “CMA CGM in preliminary deal to buy majority stake in delivery firm Colis Prive”, Reuters (31 January 2022), accessed: https://www.reuters.com/business/cma-cgm-preliminary-deal-buy-majority-stake-delivery-firm-colis-prive-2022-01-31/

- “Bank of Beirut”, Badil, accessed: https://thebadil.com/bank-profiles/bank-of-beirut/

- Hala Nasreddine, ““Cyprus Confidential”: A Safe Haven for Salim Sfeir, the Head of the Association of Lebanese Banks and the Obstructionist of Lebanon’s Recovery Plan”, Daraj (22 February 2024), accessed: https://daraj.media/en/cyprus-confidential-a-safe-haven-for-salim-sfeir-the-head-of-the-association-of-lebanese-banks-and-the-obstructionist-of-lebanons-recovery-plan/

- “Rifai Nuts sold to owner of CMA CGM“, com.lb (9 March 2021), accessed: https://www.businessnews.com.lb/cms/Story/StoryDetails/10900/Rifai-Nuts-sold-to-owner-of-CMA-CGM ; Bassam Abou Zeid and Yasmine Jaroudi, “Collaboration efforts: TotalEnergies and QatarEnergy expand partnership to solar power in Lebanon“, LBC International (27 May 2024), accessed: https://www.lbcgroup.tv/news/news-bulletin-reports/774953/collaboration-efforts-totalenergies-and-qatarenergy-expand-partnership/en

- Ray, “Business As Usual”, Badil; ”CMA CGM becomes operator of terminal in Lattakia”, Logistik Express (18 February 2009), accessed: https://www.logistik-express.com/cma-cgm-becomes-operator-of-terminal-in-lattakia/

- “State of the Postal Sector 2023 A Hyper-Collaborative Path to Postal Development”, Universal Postal Union (October 2023), accessed: https://www.upu.int/UPU/media/upu/publications/State-of-the-Postal-Sector-2023.pdf

- Ibid.

- Leila Abboud and Sarah White, ”Rodolphe Saadé”, Financial Times.

- Wayne K. Talley, Port Economics (Routledge, 2nd, 2018), accessed: https://www.routledge.com/Port-Economics/Talley/p/book/9781138952195, 605.

- Ibid, 605.

- Torsten Wezel, Hannah Sheldon and Zhengwei Fu, ”Determinants of Zombie Banks in Emerging Markets and Developing Economies”, International Monetary Fund (23 February 2024), accessed: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2024/02/23/Determinants-of-Zombie-Banks-in-Emerging-Markets-and-Developing-Economies-545110

- Mohamad Farida, ”Don’t Let It Burn: Lebanon’s Last Chance For A Progressive Deposit Recovery Plan”, Badil, accessed: https://thebadil.com/policy/policy-papers/progressive-deposit-recovery-plan/

- “Press Release: Lebanon: Normalization of Crisis is No Road to Stabilization”, World Bank Group (16 May 2023), accessed: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2023/05/16/lebanon-normalization-of-crisis-is-no-road-to-stabilization

- Ibid.

- “لبنانيون يبتكرون في التكنولوجيا المالية… منصّة التحويلات المالية Purpl لتوفير الكلفة وتسهيل التحويل,”, An-Nahar (23 April 2024), accessed: https://www.annahar.com/arabic/section/111-أحدث-الأخبار/22042023081854023/لبنانيون-يبتكرون-في-التكنولوجيا-المالية-منصة-التحويلات-المالية-purpl-لتوفير-الكلفة-وتسهيل-التحويل#google_vignette

- “Making banks from branch networks: Why financial services are still a good idea for postal carriers and retailers”, McKinsey & Company (9 July 2021), accessed: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/travel-logistics-and-infrastructure/our-insights/making-banks-from-branch-networks-why-financial-services-are-still-a-good-idea-for-postal-carriers-and-retailers

- “Corporate Profile”, Bank Audi, accessed: https://www.bankaudigroup.com/group/about-the-group/corporate-profile

- “CMA CGM’s bid to handle postal services approved: Telecoms document“, L‘Orient Today (13 July 2023), accessed: https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1343344/cma-cgms-bid-to-handle-postal-services-approved-telecoms-document.html

- Elie Ferzli, “القرم للحكومة: تجاوز قرار ديوان المحاسبة أو التمديد لـ”ليبان بوست”, Legal Agenda (24 October 2023), accessed: https://legal-agenda.com/مزايدة-البريد-القرم-يضع-مجلس-الوزراء-ف/

- “Projected Income Statement Over 9 Years for Lebanon’s Postal Sector”, Merit Invest.

- ”CMA CGM’s bid to handle postal services approved”, L’Orient Today.

- ”ديوان المحاسبة ,”قرار ديوان المحاسبة في الرقابة الادارية المسبقة”

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Philippe Hage Boutros, “Postal services in Lebanon: CMA CGM out, LibanPost back to square one”, L‘Orient Today (17 November 2023), accessed: https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1357765/postal-services-in-lebanon-cma-cgm-out-libanpost-back-to-square-one.html

- Christiane Tager, ” Postal Sector: Contract with LibanPost Renegotiated“, This is Beirut (12 June 2024), accessed: https://thisisbeirut.com.lb/economy/263159

- “ نداء الوطن” تنشر تفاصيل سجال “البريد”… والقرم يستعين بـ”الواتساب”, Nida Al-Watan (2 November 2023), accessed: https://www.nidaalwatan.com/article/220486-نداء-الوطن-تنشر-تفاصيل-سجال-البريد-والقرم-يستعين-بالواتساب

- “تحريك النيابة العامة وديوان المحاسبة وزعيتر: صفقة الرملة البيضاء تصطدم بـ«فيتو» برّي”, Al-Akhbar (29 April 2016), accessed: https://al-akhbar.com/Politics/206608

- ”Kawalis Magazine”, Facebook, accessed: https://www.facebook.com/KawalisMagazine/posts/pfbid0BHF3ZodpXAN23fpDxc5EcTxJiv5qe42woByc48h9tawz8FFqTSzNn6yYuwCCuoacl/ عوني رمضان مكرّماً من “الحركة الثقافية”: اخترت القضاء لأن تدفّق العدل لا ينضب”,”, An-Nahar (10 November 2014), https://www.annahar.com/arabic/article/187980-عوني-رمضان-مكرما-من-الحركة-الثقافية-اخترت-القضاء-لأن-تدفق-العدل-لا-ينضب

- Alexis Hachem, ”Mikati Is Calling For LibanPost To Be Investigated”, 961 (11 January 2023), accessed: https://www.the961.com/mikati-is-calling-for-libanpost-to-be-investigated/

- “Saradar Bank”, Badil, accessed: https://thebadil.com/bank-profiles/saradar/

- Ibid.

- “Our Board”, Saradar, accessed at: https://www.saradarbank.com/our-board ; Muhammad Wahba, ”Tamari Expands His Stake in ”Intra””, Al Akhbar (17 July 2013), accessed: https://al-akhbar.com/Community/54271

- Mounir Rabih, ”How was the Mikati government born?”, L’Orient Today, accessed: https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1274634/how-was-the-mikati-government-born.html; “CMA CGM commits to an ambitious university scholarship program to 440 Lebanese students”, CMA-CGM (29 November 2022), accessed: https://www.cma-cgm.com/local/lebanon/news/53/cma-cgm-commits-to-an-ambitious-university-scholarship-br-program-to-440-lebanese-students#:~:text=With%20over%202%2C000%20employees%20as,the%20increasing%20Lebanese%20youth%20emigration.

- “JOSEPH DAKKAK DÉCORÉ DANS L’ORDRE NATIONAL DU MÉRITE”, Les Conseillers du commerce extérieur de la France (15 May 2023), accessed: https://liban.cnccef.org/2023/06/25/joseph-dakkak-decore-dans-lordre-national-du-merite/

- “Digital wallets on hold in Lebanon, telecom minister stalling decisions”, SMEX (8 March 2024), accessed: https://smex.org/digital-wallets-on-halt-in-lebanon-telecom-minister-stalling-decisions/

- Lucy Barsakhian, “القرم ماضٍ بتلزيم خدمة الـE-WALLET… والحجّة: الشركتان “مش قدّها”,”, Nida Al-Watan (27 February 2024), accessed: https://www.nidaalwatan.com/article/256587-القرم-ماض-بتلزيم-خدمة-الewallet-والحجة-الشركتان-مش-قدها; “Digital wallets on hold in Lebanon, telecom minister stalling decisions“, SMEX (8 March 2024), accessed: https://smex.org/digital-wallets-on-halt-in-lebanon-telecom-minister-stalling-decisions/; Wassim Maktabi, Sami Atallah, Sami Zogheibمشروع موازنة لبنان لعام 2024: ضبط عشوائي للعجز”,”, The Policy Initiative (9 January 2024), accessed: https://www.thepolicyinitiative.org/article/details/331/lebanon%E2%80%99s-2024-draft-budget-blindly-curbing-the-fiscal-deficit?lang=ar