EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Beirut’s skyline is in perpetual flux. Constant destruction and reconstruction define the capital’s recent history: ruination in the civil war (1975-1990), reconstruction in the 1990s, expansion during the housing bubble (2005- 2010), and destruction in the port explosion of 2020. The persistent demand for cement and other building materials, combined with a class of avaricious politico- business elites, has turned the construction industry into a corrupted melting pot for politics and commerce.

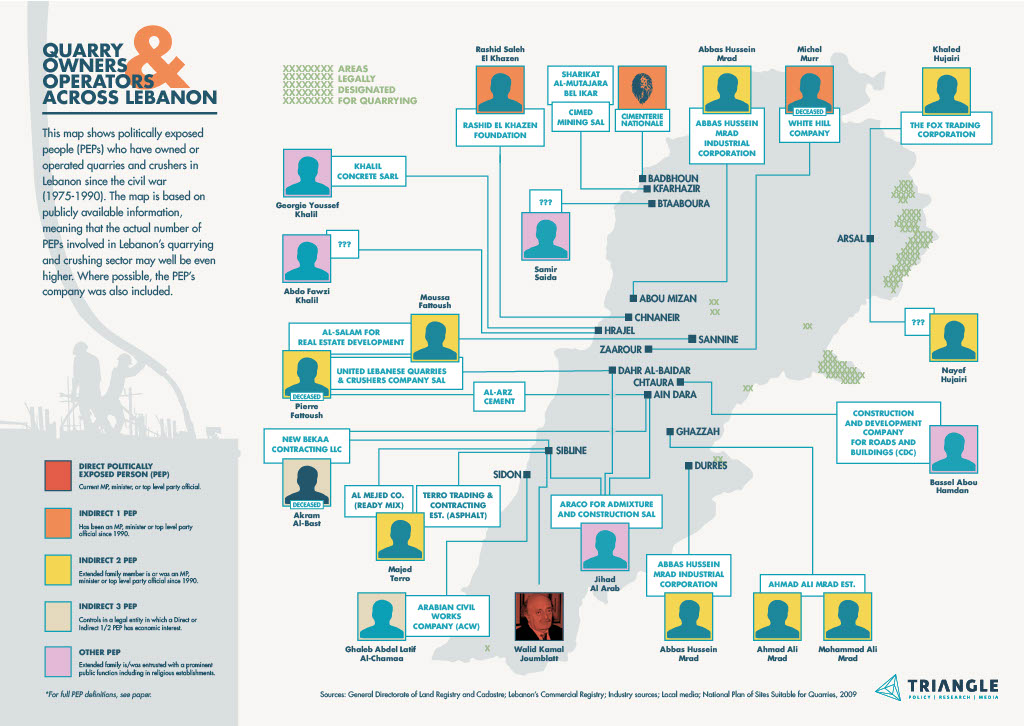

While former Prime Minister Rafiq Al-Hariri’s real estate company Solidere transformed the city’s centre throughout the 1990s, quarries worked double time to meet the country’s unprecedented demand for excavated materials. Politicians and their close circles placed themselves at the forefront of this unruly expansion; data obtained by Triangle proves that politicians or politically exposed people (PEPs) have owned at least one quarter of quarries since 1990. Almost all of these quarries exist in zones deemed illegal for quarrying. It is hardly surprising that the same group of politician-businessmen have failed to impose any proper regulation on the quarrying and crushing sector ever since.

Large amounts of excavated material find their way into cement kilns owned by Lebanon’s three-member cement cartel: Cimenterie Nationale SAL, Holcim Liban SAL, and Ciment De Sibline SAL. Here, too, political interests preside over a cement bag’s journey from mountain to mortar. At every stage of the journey, politicians and their family members are never far away: from the moment that rocks are quarried and crushed, to the processing of aggregate into cement at a production plant, and its distribution to retailers and building sites.

The three cement companies’ proximity to political power has entrenched cement production as a breeding ground for conflicts of interest – divided loyalties that protect damaging, and sometimes illegal, practices. All the while, cement and construction companies have benefited from a real estate boom, fuelled by pre-crisis subsidised loans and stimulus packages from Lebanon’s central bank, Banque du Liban. It is little wonder that politicians spurred on the real estate industry, given that these same elites own the banks that financed the boom, the plants and crushers that supplied the raw materials, and the construction companies that built gaudy skyscrapers beyond the means of most ordinary Lebanese people.

Now, faced with a stagnant real estate sector, the cement cartel is at its lowest financial ebb in decades. The construction industry’s unprecedented hiatus is the time to make a change to the status quo ante.1 Bringing accountability to these sectors demands comprehensive legal and environmental reform, combined with political vision which extends beyond short-term profits. In the long run, Lebanon’s construction sector must ween the cement cartel off their cash cows, turning instead to more sustainable foreign sources of cement and building materials. More immediately, Lebanon’s judicial system must rigorously apply the Law on Illicit Enrichment and enforce of quarrying and crushing laws which apply to existing illegal quarries.

Holding those in power to account will be no simple task, given Lebanon’s notorious culture of impunity in the construction sector. But with quantified ownership and management data for one of Lebanon’s most lawless sectors, activists and policy makers are one step closer to ending the needless destruction of Lebanon’s mountainsides.

CEMENTED INTERESTS

Three well-connected cement production companies are the most obvious culprits for the scars that run across Lebanon’s mountain faces: Cimenterie Nationale SAL, Holcim Liban SAL, and Ciment De Sibline SAL. A roster of politically influential shareholders and board members help ensure that the entire cement value chain is geared in the favour of this unholy trinity. Thanks to an effective cement import ban, for example, this corporate cartel is protected from foreign competition, leaving Lebanese consumers with one inflated price.

Cimenterie Nationale, Holcim, and Sibline also benefit from a variety of uncompetitive practices which exclude local newcomers from the sector, from price fixing to opaque licensing procedures. The cartel’s unchallenged oligopoly over cement brought it untold profits during Beirut’s property boom years. By 2018, Holcim, which controls almost half of the cement market, made almost $65 million in profits.2 Other members of the cement cartel are likely to have received similar windfalls from the artificially inflated sector. (For a more detailed analysis of market competition in Lebanon, see Triangle’s 2020 paper, Unfair Game).3

The cartel’s influence extends well beyond cement production, into the first step in the cement supply chain: quarrying and crushing rocks. Decree 8803 from 2002 and subsequent amendments explicitly forbid quarrying in any area except several remote municipalities, largely concentrated in the Bekaa valley. Despite this legislation, Holcim, Cimenterie Nationale, and Sibline extract most of the raw material needed for cement production outside of these zones, in Kfarhazir, Badbhoun, and Sibline respectively, which considerably reduces the cost of transporting materials. By owning and operating quarries outside of these designated quarrying areas, Holcim, Cimenterie Nationale, and Sibline all contravene Lebanese law (See Box I: By the Book).

These violations have brought cement companies into conflict with municipalities, who should have the right to refuse quarrying activities on their land. In 2018, for example, Kfarhazir Municipality formally requested proof of an official quarrying permit from Holcim and Cimenterie Nationale. The companies allegedly responded that they had no permits, and that Holcim was still waiting to hear a response from the relevant authorities about an application from 2016.4 In a more recent incident, Holcim referred to a permit from 1936, even though the quarrying permit must be renewed annually. Local activists also accuse Holcim and Cimenterie Nationale of paying indirect bribes to municipalities and local organisations to silence opposition to their activities.5 Holcim and Cimenterie Nationale were unavailable for comment on these allegations, while Sibline claims that it “strictly complies with all laws and regulations in force in Lebanon.”6

BY THE BOOK

Decree 8803 (2002) forms the basis of legislation regulating quarries and crushers in Lebanon, designating four remote areas of the Bekaa valley where quarries are permitted: Aarsal, Tfeil, Kousaya, and Rashaya.7 Eleven additional areas were later added,8 in which quarrying and crushing is only permitted outside of nature reserves and far from rivers.9 A successful permit must pass through the Ministry of Interior and Municipalities (MoIM), the National Council for Quarries (headed by the Environment Minister), and the relevant municipality, before being renewed annually.10 Broadly speaking, this legal framework invests the Ministry of the Environment with monitoring powers, while leaving enforcement powers to the MoIM and municipalities themselves.11 Those using a quarry without license, or with an expired license can face imprisonment of up to one year and a fine of between 50 million and 100 million Lira. If the violation is repeated, the penalty can be doubled. Confusingly, the National Physical Master Plan of the Lebanese Territory (NPMPLT) – endorsed by the Lebanese Cabinet in July 2009 – was intended to supersede all previous regulation of quarries and crushers. However, Decree 8803 and its amendments remain the main framework for quarries and crushers.

ABOVE THE LAW

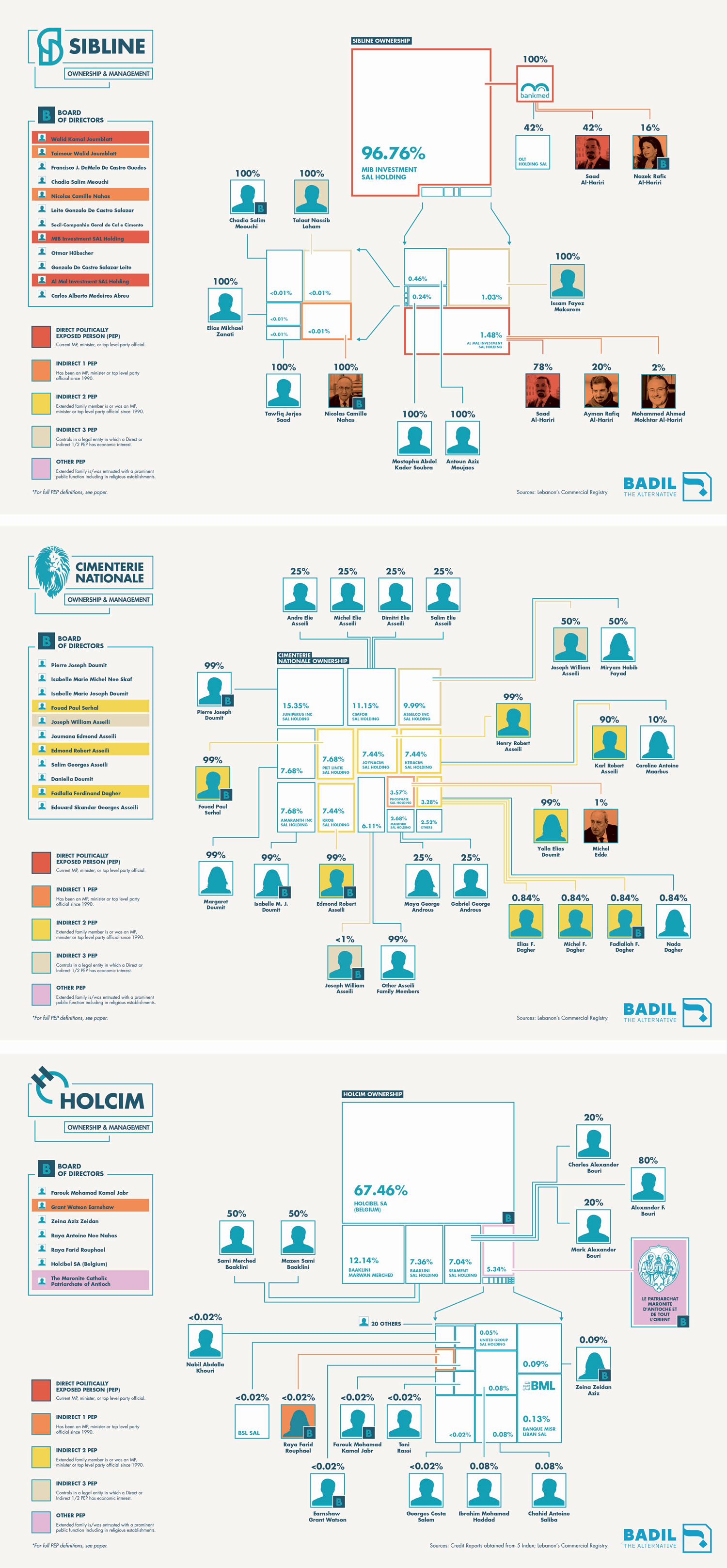

The cement cartel is able to bypass quarrying and crushing laws thanks to its considerable economic and political clout, reflected in the ownership and management of the three companies. Triangle’s investigation used multiple sources to corroborate data from the Lebanon’s Commercial Registry, revealing dozens of politically exposed people (PEPs) amongst the cartel’s shareholders and boards of directors.

DEFINING CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Conflicts of interest occur when an individual or a company can exploit their own professional or official capacity in some way for personal or corporate benefit.12 This report identifies conflicts of interest in Lebanon’s cement industry, by identifying and classifying politically exposed persons (PEPs) who are in a position to benefit from conflicts of interest. Conflicts of interest are ascertained through an analysis of ownership (shareholders) and management (boards of directors) of various companies involved in the cement and construction sectors. Triangle categorises PEPs into the following five groups:

Direct Politically Exposed Person (PEP):

Person is currently a Member of Parliament (MP), Cabinet Minister, or (mutually exclusive) leader/top level official from a political party which took part in the violent conflict during the Lebanese Civil War from 1975-1990.

- Indirect 1 PEP: Person has been an MP or minister since 1990, or (mutually exclusive) leader/top level official from a political party which took part in the Lebanese Civil War.

- Indirect 2 PEP: Person’s extended family member (extending to grandparent, [great] aunts/uncles, nephews/nieces, cousins) is or was an MP or Minister since 1990s, or (mutually exclusive) leader/from a political party which took part in the Lebanese Civil 13

- Indirect 3 PEP: Person has ownership or management control in a legal entity in which any of the persons who are classified under Direct/Indirect 1/Indirect 2 has economic interest.14

- Other PEP: An individual whose family may be or may have been entrusted with a prominent public function by a foreign or domestic government including in religious establishments.15