EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Lebanon’s economy might look like a storm-stricken boat, adrift at sea with a broken rudder, a shattered mast, and – crucially – no captain or crew. But this media-friendly narrative of chaos and inevitable decline only tells half of the story.

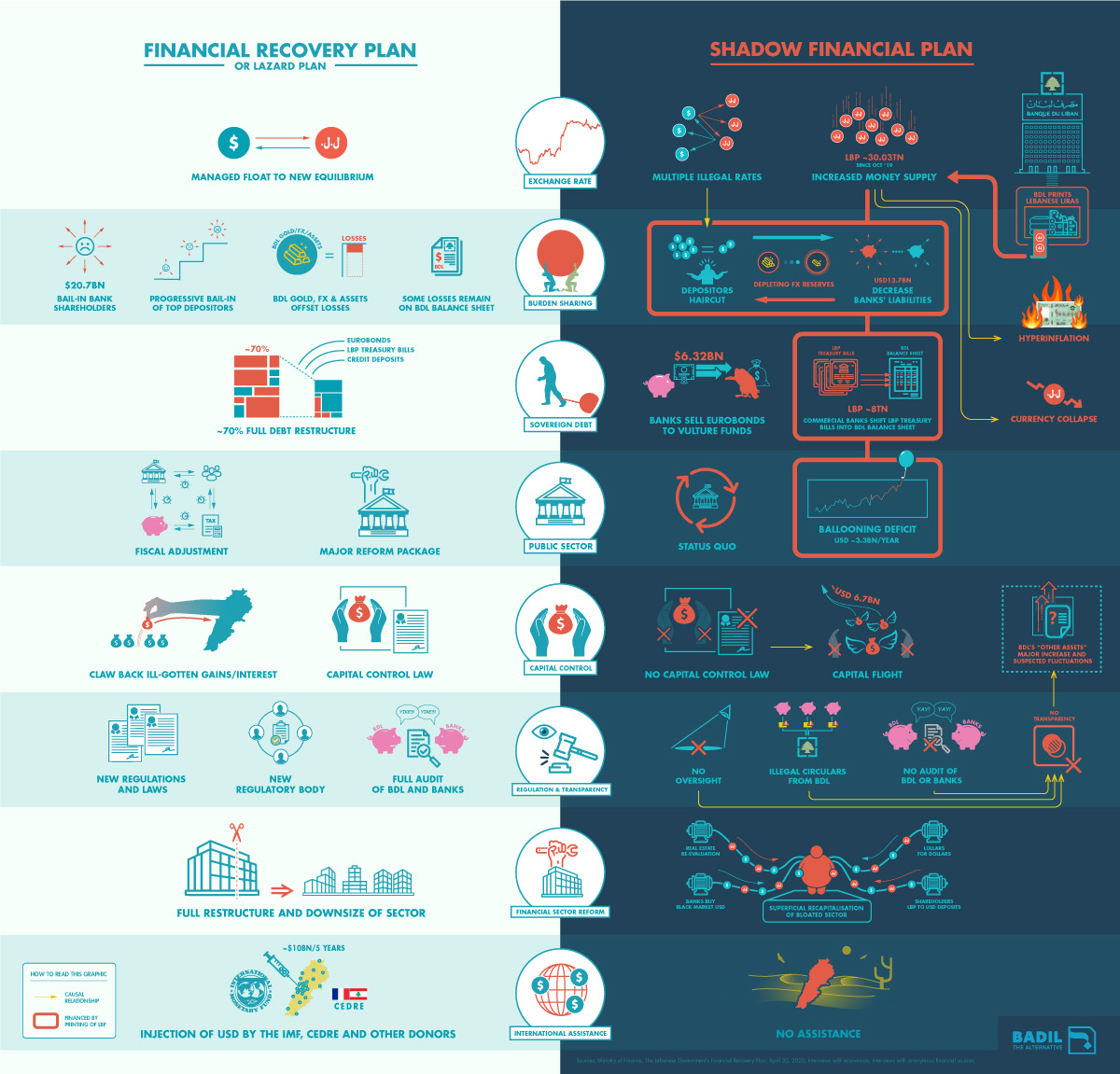

In fact, far more malevolent forces are setting this ship’s course. In the absence of a functioning government, left unsupervised at the helm are Riad Salameh, the unelected governor of Banque Du Liban, Lebanon’s central bank, and a small group representing elite economic interests. While the Lebanese people weren’t looking, they hatched their own “Shadow Plan.”

Unfortunately, the Shadow Plan amounts to more than simple crisis management. Rather, Lebanon’s wayward captains are heading full tilt at the rocks, sheltering the richest from bearing their fair share of the financial burden. The plan shifts the system’s vast losses away from banks’ balance sheets, onto small and medium sized depositors, and the wider population in general.

Illegal multiple exchange rates and printing Lebanese Lira are the most obvious features of this Shadow Plan. This devastating reality is crippling the Lebanese people through inflation, imposing a forced haircut on depositors, and eviscerating their savings. Meanwhile, the same policy of increased money supply is whittling away banks’ liabilities, by giving depositors their savings at rates far lower than the black market. As the banks recoup the difference, they slowly but surely reduce their share of the losses.

Still more troubling decisions lurk deeper in the shadows. To add salt to the wound, the BDL is covertly reducing the commercial banks’ exposure to unserviceable government debts, shifting future losses from their balance sheets onto its own.

Other insidious polices are enabling the banks to create capital and liquidity out of thin air by little more than accounting chicanery. Circular 567, for example, permits banks to re-evaluate their real estate portfolio to current day values as a means to bolster their capital. Measures like this have no impact on banks’ real liquidity undermining the whole objective of the recapitalisation process.

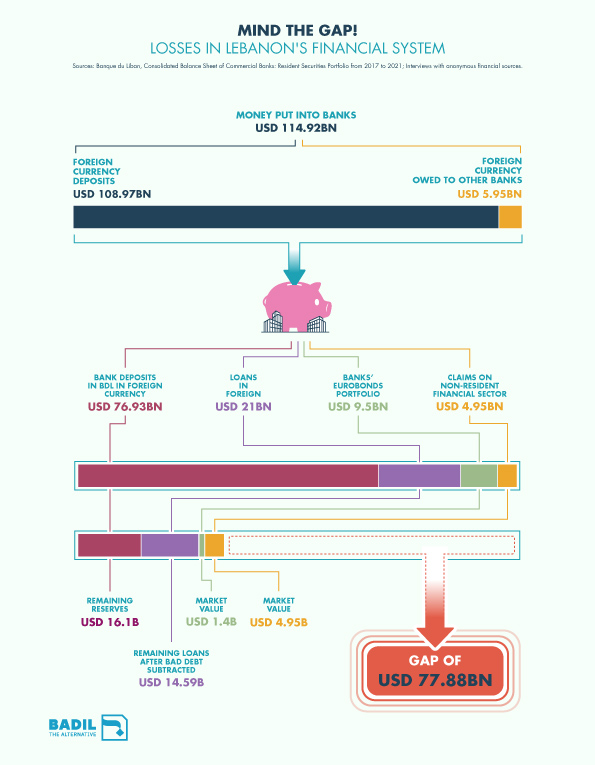

The effects of this Shadow Plan are plain to see: the Lebanese Lira has lost 90 percent of its value; over half the population live below the poverty line; the economy shrank by 40 percent last year. In fact, the freefall is so severe that predictions of the future are guesswork at best. Commercial banks continue to hide behind their hands, claiming that they still have foreign currency liquidity.

The latest aspect of the Shadow Plan to be revealed is an initiative to repay depositors their savings in foreign currency up to $25,000 per person. But the policy – which will ostensibly be unsustainably financed by the BDL’s foreign reserves – amounts to little more than a bribe to placate the public temporarily. More importantly, the initiative fails to address the real losses in the financial system, meaning that depositors are unlikely to see their full deposits any time soon.

But the Shadow Plan is not a foregone conclusion. Acknowledging and understanding how this apparent policy of inaction is fuelling and shaping the ongoing crisis is the first step towards challenging it. With political will and focused pressure from civil society, not to mention the leverage of international support packages, a more equitable and sustainable alternative is possible.

TOO GOOD TO BE TRUE

Congratulations to Lebanon. Today, I can announce that the country has a comprehensive and historically unprecedented plan to end the period of political and economic instability which brought the country to a state of collapse.”1

Just over a year ago, the Lebanese premier Hassan Diab promised to do the impossible: solve Lebanon’s economic morass with a single plan. The Financial Recovery Plan (FRP), also known as the Lazard plan or the Government Reform Plan, outlined boldly ambitious and far-reaching reforms.

Diab’s optimistic tone has not aged well. But despite the past year’s continued economic decline, the FRP deserves some credit for providing a blueprint for some sort of holistic reform. Many analysts welcomed the FRP as the only comprehensive policy response to the country’s multiple crises to date, even if others felt it did not go far enough (See Box I).2 It even had the seal of approval from Lazard, a respected financial advisory firm.

Flawed but functional

While preferable to the Shadow Plan that replaced it, the FRP was not a panacea. The plan focused largely on tackling the banking and currency crises while paying less heed to addressing inequality and the social impacts of Lebanon’s various crises. The FRP’s suggested austerity measures, such as cutting public wages and pensions, would have exacerbated the devastating social impacts of Lebanon’s recession and currency crisis. Similarly, many tax measures recommended in the FRP were regressive, including raising electricity and gasoline prices, whilst failing to push taxation to more than 15 percent of GDP. Moreover, the plan’s proposed cash assistance to help businesses during the COVID-19 pandemic amounted to a mere two percent of GDP, a fraction of the amount invested by many countries.3

First and foremost, the plan proposed immediately scrapping the outdated Lebanese Lira peg, replacing it temporarily with a more flexible “managed float” of the exchange rate.4 Until an International Monetary Foundation (IMF) deal was finalised, the plan envisaged that the BDL would spend between $500 and $700 million of its foreign currency reserves to stabilise the currency.5 Then the injection of liquidity from international donors would have provided the necessary balance of payments support for a managed or “crawling” peg. This would sustain a transitionary period until the economy was ready to move to a free floating exchange rate.

Next, the FRP would have restructured the government’s debt, writing off nearly three quarters of government bonds in both local and foreign currency – in other words, a debt haircut. In most sovereign debt crises, international investors stand to lose the most when debt is cancelled. However, since Lebanon’s financial crisis was largely homegrown, the vast bulk of the debt is held by the BDL and local commercial banks. Therefore, Lebanese commercial banks—who made billions of US dollars in interest on the debt prior to the crisis—would have been the ultimate losers from a comprehensive debt restructuring.

However, restructuring the total government debt would only solve part of the problem, since some 70 percent of total losses in the system are embedded within the BDL and commercial banks. The real black hole lay at the heart of the BDL. It arose not just from exposure to the sovereign debt, but also the BDL’s myopic decision to fund the unsustainable currency peg.

The plan faced limited options when addressing these gargantuan losses. A foreign bailout was off the cards;6 since the 2008 global financial crisis, international practice has shifted away from the idea that a failed financial system should be supported by public money, especially in times of global recession such as the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.7

The chances of the government itself raising enough money were equally improbable. Even a functioning government would have found it impossible to raise sufficient revenue by selling its dilapidated assets. Due to the country’s financial predicament, such a decision would have amounted to a pointless fire sale. Besides, the FRP rightly viewed such a policy as ethically indefensible since it would have propped up a broken system at the expense of the current population and future generations of Lebanese.

Instead, the FRP proposed a three-pronged approach to covering the losses. Firstly, a bail-in of the banking sector would draw on banks’ shareholder capital and the savings of large depositors. This policy proved extremely unpopular ultimately leading to the FRP’s eventual downfall (See: Passing the Buck).

In addition to the bail-in, the Lazard plan assumed that the BDL would also take on a share of the losses, by using its gold and foreign currency reserves. In this scenario, $3.9 billion would have remained on the BDL’s books, with an aim to whittle them down over the coming years.8 Finally, the plan would have attempted to claw money back from those who illegally profited from their position in government, by imposing a forensic audit of all public contracts.

Of course, the plan did not naively ignore the necessity of financing from the international community. The success of the plan was predicated on a major injection of liquidity from various donors, most notably from the IMF. An estimated $10 billion over a five year period would have enabled the managed readjustment of the currency and stabilised the country through a period of major fiscal and macro-economic reform, as outlined in the plan.9

Diab’s recovery plan was not perfect. Nonetheless, it remains a commendable attempt to create a foundational base for future reform.

PASSING THE BUCK

Just months after its unveiling, the plan was dead in the water. The FRP immediately drew vociferous opposition from the wealthiest and most politically connected corners of society who conspired to assassinate the programme.10 The loudest voices came from those who would have been hit hardest, namely bank shareholders and large depositors.

The architects of the FRP viewed banks’ shareholders either as willing accomplices to the country’s precarious Ponzi scheme (See Box II) or simply blind fools. Either way, they were equally responsible for the resulting financial chaos, the plan’s architects argued. The writing was on the wall. Prior to the crisis, Lebanon had not been an investment grade country for almost a generation; a budget had not been passed in more than a decade, and endemic corruption was the defining feature of government. Whether knaves or fools, the plan held shareholders accountable for how they had invested their depositors’ cash.11

Original sin

Lebanon’s original sin lies in its currency peg, which artificially preserved a playboy’s paradise for many years. Since the once-steady inflow of foreign currency began dwindling a decade ago, the BDL’s governor Riad Salameh has pursued complex, opaque, and increasingly risky policies to attract foreign currency into the country and keep the Lebanese Lira pegged to the US dollar at 1,507.5. The peg was always fragile as long as Lebanon was reliant on imports for most of its material needs and had little in return to export. Over time this imbalance was maintained by a voracious financial sector that, at its peak in 2018, held deposits worth more than three times the country’s GDP. About two-thirds of deposits were in dollars. To maintain this hugely inflated financial sector Lebanon had to attract ever larger quantities of fresh dollars into the system. “Financial engineering,” for example, allowed Lebanese banks to offer exorbitant interest rates to depositors to keep the dollars flowing in. In turn, the banks would use these dollars to buy certificates of deposit from the BDL. It was only a matter of time until this flawed strategy resembling a Ponzi scheme came crashing down. For a more detailed treatment of the causes of Lebanon’s ongoing economic crisis, see Extend and Pretend, 2019.

Therefore, instead of a bailout of the banks, the reform plan proposed a massive bail-in of the banking sector, forcing the richest individuals to foot the bill. This measure would have largely wiped out existing shareholders, forcing them to contribute around $20.7 billion from their own capital base. This amount would have helped write off banks’ capital against their losses.

Meanwhile major depositors would have seen a progressive bail-in, in which significant portions of their deposits would be turned into shares. Those depositors could sell the shares once their banks were returned to a solid base. In this scenario, medium and small depositors would be largely unaffected. In order to aid this process, the plan demanded a forensic audit of the BDL. It also stipulated a clawback from those who had profited nefariously from public contracts.

These aspects of the plan proved deeply unpopular among banks’ owners and large depositors. In a letter to Lazard, the Association of Banks in Lebanon (ABL) – which represents the interest of commercial banks – expressed its “disappointment in the government’s approach” since “current shareholders will be totally wiped out and thrown ”12 The ABL argued that the responsibility for the crash lay with the government and BDL for having overseen so many years of profligate and wasteful spending.13 In a counterplan, the ABL rejected the need for debt and financial sector restructuring.14

These lobbying tactics were effective because wealth is highly concentrated within Lebanon’s banking system. According to the IMF, the Lebanese banking system had just over 1.6 million accounts at the end of 2015, of which 16,000, or 1%, accounted for 50% of the value of deposits. Less than 0.01% of depositors, or 1,600 accounts, alone held 20% of the deposits, with an even greater concentration for dollar deposits.15 With such enormous economic and political clout, banking lobbyists quickly torpedoed the deal. Soon after, the government collapsed and talks with the IMF stalled.

THE SHADOW PLAN

A conspicuous silence followed the FRP’s untimely demise. Diab’s government and Lazard did not go back to the drawing board, neither was a new plan started with different consultants. One would be forgiven for thinking that the caretaker government is acting without a plan.

But upon closer analysis, the past year has borne witness to a number of policies, both explicit and implicit, that are shaping the trajectory of Lebanon’s demise, ultimately determining who wins and who loses (See Figure I). The measures adopted in the Shadow Plan range from contentious to downright illegal. Picking apart this “Shadow Plan” requires Holmesian levels of detection.

The first clues lie in the money supply. Lebanese Lira in circulation outside the BDL – in other words printed money – increased from 6.47 trillion to 36.5 trillion Lira between October 2019 and end of March 2021.16 This tsunami of cash gushing through the system is exacerbating the crash in the exchange rate and fuelling runaway inflation, both of which are crippling ordinary Lebanese citizens.

Inflated money supply is nothing new. But in the past, the BDL and banks sheltered the real economy by offering high interest rates to disincentivise withdrawing money or by letting people convert their money from Lira to dollars at 1507.5 Lira to the dollar through the banking system. Instead of withdrawing their money and going to buy dollars, they could just do it on paper, which did not require anyone to actually supply the dollars.

But upon realising that very few dollars actually exist in the system, depositors wanted to convert their Liras to real dollars or spend it before it lost even more value. To do so, the BDL printed Lira.

SHIFTING THE DEBT

In the spring of 2020, Diab’s government entered negotiations with the ABL to agree on a way to restructure domestic treasury bills – in other words, government debt in local currency. But after the FRP was blown out of the water, the talks quickly stalled.

Despite this apparent stasis, commercial banks’ share of treasury bills has been decreasing since the beginning of the financial crisis proper. Some 7.64 trillion Lebanese Lira in the commercial bank’s domestic treasury bills were settled between October 2019 and February 2021.17

Meanwhile, the BDL’s share of treasury bills has been increasing. This is partly due to its financing of the fiscal deficit. But that does not account for the whole increase. In fact, away from the media spotlight, the BDL has been taking on government debt from commercial banks. In order to do so, the BDL has been printing Lira.18

The consequences of this policy are manifold. Firstly, when any future government returns to the negotiating table with the domestic banks its bargaining power will have been significantly eroded. Losses from any future negotiated default will have migrated from the banks’ balance sheet to the balance sheet of the BDL. This may even make restructuring of the transferred debt impossible, as the initial plan didn’t include the restructuring of the debt held by the BDL, to avoid accumulating increased losses in the BDL’s financial statements.