MASSIVE COSTS, MINIMAL SERVICES AND TOKEN TRANSPARENCY

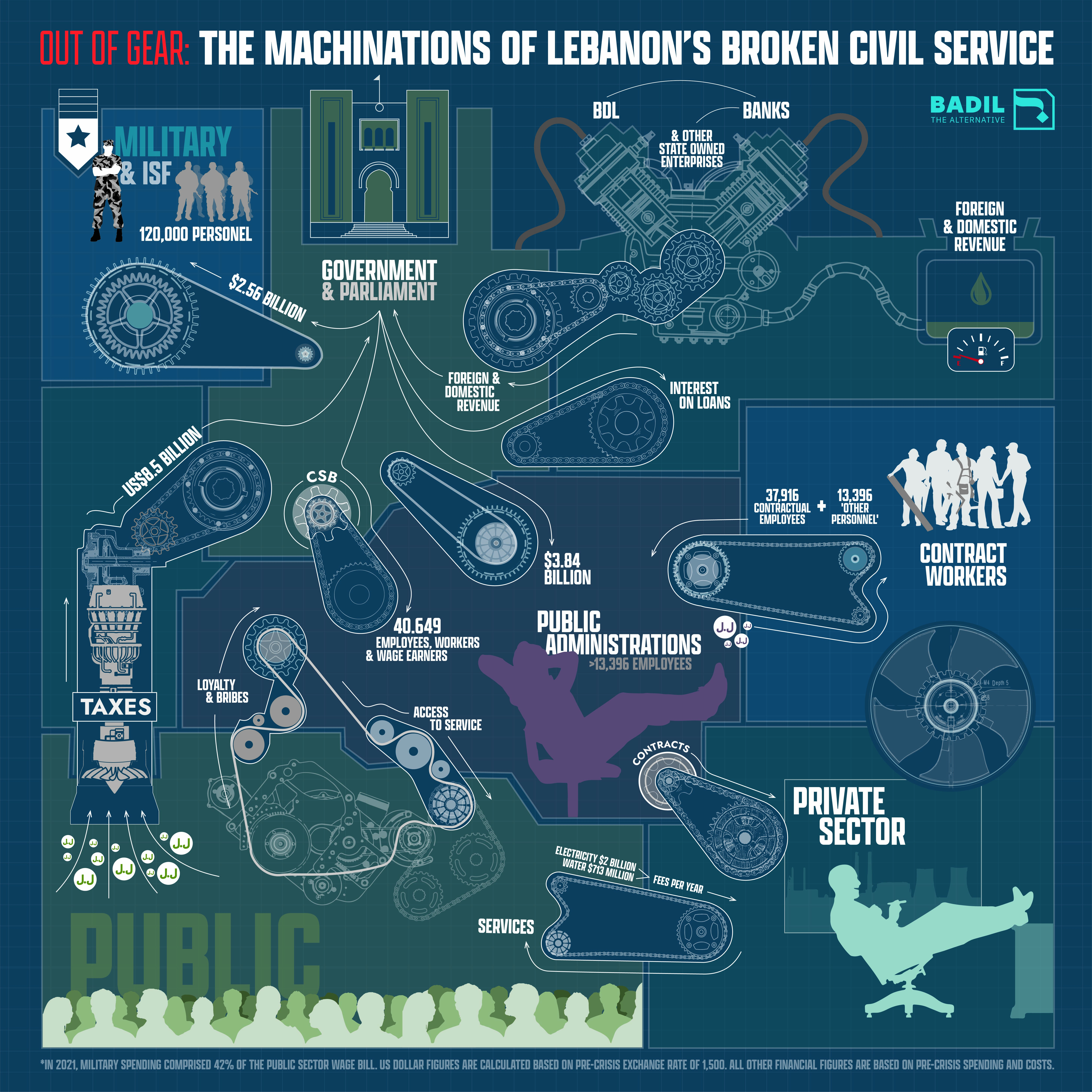

Clear data on the number of civil service employees, salaries, and performance indicators are woefully lacking. No clear numbers exist for public administrative bodies operating “off-budget”, meaning for which budgetary spending is not reported transparently to the Ministry of Finance. There are numerous ghost entities which draw salaries but have not operated for years, such as Lebanon’s Railway Administration.[22], [23], [24] When mandated by a subsection of the 2019 budget law to do a survey of their human resources, many public administrations and establishments did not submit the required documents, among them being the Supreme Islamic Shiite Council, the Sunni and Jaafari Spiritual Courts, the Directorate General of General Security, and General Inspectorate of the Internal Security Forces.[25],[26] Further, the survey did not take into account the public administrative bodies which do not fall under the purview of the Civil Service Board, with the number of bodies this includes being unclear.[27] Without full data, the resulting survey calculated there were at least 91,000 civil servants. This number includes at least 38,000 contractual staff but excludes military and security institutions, which are estimated to employ 120,000 personnel.[28]

Box I: The LAF

Despite its reputation as being more respectable and neutral than the broader civil service, the Lebanese Armed Forces have not escaped the influence of sect-based appointments and the use of employment as a source of patronage. While there is an effort to maintain a 50/50 Muslim-Christian split overall in LAF ranks, senior roles within the LAF are also specifically designated to religious sects. The LAF commander must be a Maronite Christian, the Chief of Staff a Druze, and four generals must represent the Sunni, Shia, Greek Orthodox, and Greek Catholic communities. Sectarian power-sharing games have allegedly exposed the LAF to political maneuvering and co-optation of appointments to leadership positions.

The LAF’s experience – both before and after the 2019 crisis began – mirrors that of the civil service. Prior to 2019, more than 71 percent of the LAF’s total budget went toward staff salaries, benefits, and pensions — while in a nation like France the armed forces spends only 32 percent of its funds for this purpose. The LAF’s inflated salary costs partly derive from the high ratios of senior ranking officers. These officers receive higher salaries and, importantly, higher retirement pensions. Instead of 160 general-grade officers — as the LAF’s official command structure calls for — there may be as many as 400 general-grade officers currently serving. At around 80,000 servicemen, the overall size of the LAF has grown four-fold since 1974.

Since the 2019 crisis began to severely depreciate the value of salaries paid in Lebanese lira, the LAF has also experienced a crisis in morale and attendance. As with other public sector workers, most servicemen have seen the value of their salaries reduced to less than US$50 per month. In response, the LAF has permitted soldiers to take multiple days off per week to work second and even third jobs, reducing the number of soldiers on duty each day by around 50-60 percent. Further, some 2,000 soldiers deserted the army between 2019 and 2021, shrinking the force for the first time since 2007.[29]

Despite the overall size of the civil service being widely regarded as exorbitant relative to the services it provides, official figures provided by ministries show that more than 70 percent of full-time positions are vacant, at least officially.[30] The contradictions in this overall picture are multiplied by the fact that certain sectors of the civil service, such as education and Électricité Du Liban (EDL), are heavily bloated with unnecessary contract workers. Again, poor data availability and record-keeping means it is unknown whether the vacancies in full-time positions are actually being filled by contractual or daily workers. It is estimated that thousands of officially vacant roles are no longer necessary. Poor mobility between ministries has also led to misallocation of staff in some agencies and shortages in others.[31],[32]

How much each civil servant is really paid also remains unknown. Despite the existence of an official salary scale,[33] the actual take-home pay of civil servants is often determined by an opaque and ad-hoc system of awards and benefits. [34],[35] From 2010 onwards, the weight of the public wage bill on the budget grew faster than any other expenditure and by 2018 reached 38 percent of all government spending. While the total public expenditure as a percentage of GDP was lower than comparable countries such as Cyprus and Jordan, Lebanon’s low tax collection rates meant that most available government revenue was eaten up by just three budget items: public sector wages, debt financing and transfers to EDL.[36] In 2017, the cabinet issued a public hiring freeze, ostensibly recognizing the unsustainability of continuing to inflate the civil service.[37] Despite this ban at least 1,400 staff were hired illegally between August 2017 and August 2019 within ministries alone.[38] The hiring freeze by default further politicised civil service employment by making contractual and daily workers the only way of hiring, subject only to ministerial prerogatives.[39]

Box II: Permanent, Contract and Daily Workers

Contractual workers present an easy target for criticism regarding the over-staffing present in the Lebanese civil service, as they can be hired directly by ministries and other administrations with little oversight. Their numbers have also vastly increased in the post-war era to represent nearly half of all accounted-for workers.[40]

The hiring of contractual workers accelerated in the post-civil war era.[41] In some areas such as education – which is by far the largest non-security public sector employer – this has seen contractual workers grow to comprise 60 percent of the workforce. In other areas, however, contractual workers fulfill important roles not covered by the Civil Service Board (CSB), the government department mandated to carry out public sector recruitment in Lebanon. The CSB’ job profiles are generally regarded as outdated and missing critical positions necessary in a modern administration, such as in information technology[42], [43], [44], [45]

Patronage-based hires also pervade CSB appointments. Once full-time staff pass CSB exams, their appointments are subject to control by ministers and other political appointees, and the monitoring of their performance is up to each individual ministry alone. Unlike contractual workers, who can be dismissed if a minister sees fit, full-time workers are often in their roles for life and are very hard to dismiss via institutional review mechanisms.

Another workforce is also at play in Lebanon’s civil service. Since 1992, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) has been supporting a parallel stream of highly skilled employees within the civil service. In 2010, this project to support civil administration with new staff structures and highly skilled staff included 67 projects across ministries and administrative bodies. The UNDP workforce within the civil service has been so extensive and effective – in comparison to other employees – that it has become responsible for a significant level of public service delivery.[46]

Socially, the decades-long abuse of the civil service has degraded staff morale and the service’s reputation among Lebanese, with public trust in the system low. Prior to 2019 only 20 percent of Lebanese trusted core public institutions[47] and no state services – except for security forces in the south, Nabatiyeh and Bekaa – scored more than 50 percent satisfaction.[48] Within the civil service, the knowledge that many employees are there for a free ride, or to actively impede reform, has acted as a general drag on morale.[49] A 2016 survey of more than 450 public servants found that the majority were strongly aware that their careers were dependent on political patronage.[50] A 2021 survey found that 82 percent of civil servants did not believe promotion was based on competency, with nearly 40 percent believing it was based on nepotism.[51]

Many administrative leaders and their staff are not fully aware of their roles and responsibilities, especially in relation to other administrative bodies. The overlapping and competing mandates of many ministries, public administrations and other state bodies extends from the often-vague phrasing of their legal mandates, language that allows them to both escape responsibility and claim jurisdiction, as desired. [52],[53]

Box III: The Civil Service Board

Lebanon’s Civil Service Board (CSB) – the body ostensibly responsible for civil service recruitment – was established in 1959 to address human resource deficiencies and misuse of public funds.

The CSB was supposed to implement merit-based hiring through examinations and distribute candidates to ministries in bi-annual hiring rounds. Whilst the CSB‘s establishment had the potential to initiate a shift towards meritocratic hiring practices, like all public administrations in Lebanon it has also been vulnerable to cooptation by political appointments within its ranks and drifted into ineffectiveness despite its crucial role.

By the end of the civil war the CSB had lost its ability to meet the hiring needs of ministries, which had elevated and specific recruitment needs to support reconstruction. It was in this period that the recruitment processes and tests implemented by the CSB fell further behind the needs of a modernising workforce. [54]

The CSB model’s inflexibility also influenced its declining relevance. For example, ministries must wait up to two years, in line with the CSB recruitment cycle, to receive new staff. Furthermore, the CSB can only create vacancies for which there are equivalent recognised qualifications at the Lebanese University.[55] The CSB’s inflexibility and standards thus dually incentivised direct contractual hiring by ministries, and circumvention of the CSB’s standards.

To date, the CSB has not updated its testing and hiring protocols since the 1990s to match the needs of a modern workforce, and there has not been a comprehensive analysis of the types and numbers needed in a modern public service. The CSB and its sister institution the Central Inspection Bureau – which has a mandate to monitor violations within public administrations, institutions, and municipalities, as well as undertake studies of necessary reforms – fall under the control of the Prime Minister and the results of its surveys and recommendations are subject to approval by the Council of Ministers.[56][57],[58]

KEY BLOCKAGES TO REFORM

Before Lebanon’s ongoing economic crisis began in 2019, the civil service afforded Lebanon’s ruling elite bi-directional resource control, whereby they distributed favours via the civil service and kept the population reliant on those favours through a lack of public services.[59] At the same time, politicians have used emotive and historical appeals of ‘defending the sect’ to justify their continued division of the state along sectarian lines.[60]

The centrality of this model can be seen by the amounts of money Lebanese governments have spent on public sector salaries and transfers to Électricité Du Liban – the latter of which is a state-owned enterprise that reflects both the problems rife in the civil service, as well as the impact on the public who must turn to the private sector for electricity.[61] These two budget expenditures, along with debt servicing, comprised 80 percent of the 2018 budget.[62]

Since 2019 and the dramatic depreciation of the lira, the patronage facilitated by civil service employment has broken down. As the value of civil servants’ salaries have plummeted, strikes have swept the public sector – particularly in education and the judicial system – paralyzing much of the state.[63] Losing their ability to maintain their patronage networks through the civil service would be a major blow to Lebanon’s sectarian elite, as it is fundamental to their political legitimacy and sway within their religious communities. The government has acted repeatedly to try to repair its bonds with the civil service through salary increases: since Lebanon’s financial and economic crises began in 2019, 75 percent of the funds the government has spent on social protections have gone to government employees, even though they comprise only 20-25 percent of the labour force.[64] The political elite has, however, undermined its own efforts by not addressing the currency depreciation and price inflation symptomatic of the financial crisis.

Over the decades, despite the millions of dollars poured into civil service reform by international donors and a dedicated state institution for such[65] – the Office of the Minister of State for Administrative Reform (OMSAR) – Lebanon has seen little change in the efficiency of it civil service. This is because efforts to address phenomena such as mismanaged funds or illegal hiring gain little traction without political incentive to change the system, or an independent judiciary to address the regular legal violations.[66] The judiciary is also an arm of the civil service and likewise suffers from political interference.[67] The political and sectarian saturation of the state administration and judiciary has effectively negated the separation between legislative, judicial, and executive arms of government.[68] This is particularly evident in the role of administrative courts, which should theoretically have the power to annul unconstitutional acts or decisions taken within the state’s administrative apparatuses, such as the allocation of civil service positions along sectarian lines below first grade positions.[69]

Box IV: Privatisation

Privatisation of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and their services has long been floated by policy analysts as a way of circumventing the inefficiencies of the civil service, and more recently as a way of generating revenues to resolve the financial crisis.[70],[71],[72] Proponents of partial or full privatization and public-private partnerships (PPPs) point to the advantages to be gained from opening SOE service delivery to competition, private companies’ efficiency prerogatives, and greater transparency. Regardless of its potential merits, however, politicians have historically rejected privatisation on sloganistic grounds of defending the public interest and keeping resources in state hands. This should be seen as largely empty rhetoric, given that through overseeing the failure of essential service delivery from state bodies, politicians have supported unregulated privatisation in areas such as fuel generators and water supply – with many of these private providers themselves affiliated with the political class.[73], [74]

Lebanon has a handful of SOEs that could be privatised, including Électricité du Liban, Casino du Liban, Middle East Airlines, and Régie des Tabacs et Tombacs. The optimal degree of privatisation, the level of attractiveness for private investors, and potential risks and dividends associated with privatisation differ for each SOE.[75] Some SOEs are revenue generating, in particular the telecom sector and the port of Beirut, which contributed between 11 and 14 percent of public revenues during the five years prior to the ongoing economic crisis.[76] Privatisation of these SEOs would need to result in significant service delivery gains and wider dividends for the economy at large to compensate for the loss in government revenue.

In general, whether or not privatisation leads to broadly positive outcomes largely depends on the associated regulation of the sector and whether actual competition is introduced into the market (rather than a public monopoly simply becoming a private one).[77] In Lebanon, an additional consideration is whether privatisation would in fact remove the political interference prominent across much of the economy (i.e., selling a state asset into the hands of a private company owned or affiliated with a political figure is unlikely to result in broadly positive outcomes).[78] Privatisation is not, however, a feasible or realistic emergency solution for Lebanon’s financial crisis and should be undertaken only when the government is in a position to negotiate a fair selling price for the SOE and the proper regulatory preconditions are in place. PPPs have also been assessed as feasible in other areas such as telecoms, roads and transport, and power plants (renewable and hydrocarbon).[79]

On aggregate, SOEs’ contribution to government revenues is marginally positive and would be far higher if not for the profligate spending required to keep the highly dysfunctional Électricité Du Liban afloat.[80] The financial burden of EDL could potentially be reduced or eliminated through properly regulated privatisation. Lebanon’s never-implemented Law 462 enables up to 40 percent privatisation of EDL and public private partnerships in electricity generation and distribution, while maintaining transmission in government hands. Private sector involvement has been assessed as essential to free up competition in electricity generation and distribution, while maintaining government control as middleman over important infrastructure.[81]

In Lebanon’s current context, however, it would be unwise to proceed with privatisation, given the lack of adequate regulatory frameworks to ensure Lebanese consumers are not left worse off. Lebanon’s high-risk context and dysfunctional banking sector entail that, at present, it would be difficult to find reputable companies willing to invest in Lebanon on reasonable terms, meaning the most likely candidates would be politically exposed companies. The levels of risk and borrowing required to conduct major infrastructure projects at present would also make private sector projects far more expensive than if the government conducted them.[82]

LOOKING AHEAD

The political culture underlying Lebanon’s civil service has been incompatible with an equitable modern state since independence. The current breakdown of relations between the state, its administration, and the public, while disastrous on many levels, also presents an opportunity to remake this key element in Lebanon’s social contract.

In an ideal world, the system would be completely remodelled with no underlying sectarian blueprint. Given the near impossibility of such an effort in today’s Lebanon, stakeholders should push for reforms that: a) make the civil service more financially sustainable, b) increase merit-based recruitment and staffing c) improve public service delivery. These pillars should be prerequisites until there is broad consensus in Lebanese society that sectarian identity is no longer the basis on which the political system or the civil service should be constructed and maintained in practice. Core to implementing these efforts will of course be instituting stronger barriers between the state’s bureaucracy, judiciary and political leadership.

As highlighted by the discrepancy between the vacancies in full time civil service positions and the excess of contractual and unqualified staff in other areas, there is no one-size fits all approach to reforming the size and structure of Lebanon’s civil service. Each branch of the service must be rationalized according to a forensic audit of its human resources and realistic financial capacities. This is likely to mean thousands of unnecessary employees, whether full time or contractual, will need to be let go with appropriate severance packages and social protections in place.

At the same time, hiring practices will need to become more flexible to adapt to the varied needs of different administrations and the changing skills profiles of the workforce. Hiring practices will also need to be insulated from political influence – both through the establishment of judicial independence as well as reforms to increase the transparency of procurement procedures within public institutions.

Donor agencies focused on civil service reform and social protection can play an important role in mediating the transition of the thousands of workers who must be let go. At the same time, all recommendations need international pressure to incentivize genuine reform among the political class, such as through making international financial support conditional on the implementation of reforms and sanctioning those deemed to be impeding the reform process.

The following recommendations are offered as entry points to begin the extensive reform process needed for Lebanon’s public institutions to begin fulfilling their basic mandate, which is to deliver services to the Lebanese public.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Every public institution should make all human resources data available to an external auditor in order to conduct a forensic audit of staffing, staffing needs, and staff expenditure. This forensic audit is the first step in rationalising and redistributing the overall human resources pool. The external auditor’s mandate must include assessing the necessity of existing contract workers, the level of transparency in contract worker recruitment, and the monitoring and accountability mechanisms in place once they are hired. The assessment should also address the potential for digitisation to improve efficiency and update staffing needs across all public administration bodies. Contractors who are qualified to fill empty permanent positions should be encouraged to join the civil service. The Office of the Minister of State for Administrative Reform (OMSAR) should be empowered to incorporate the results of the forensic audit into its reform proposals and to implement them.

An assessment of the options for reforming the civil service board is essential. The assessment should seek the best model which establishes both independence from political co-optation and creates an efficiency incentive for all public hiring. This survey would consider all reasonable options, including the transfer of civil service board prerogatives to an external auditing company. This new body could, for instance, be given a mandate to implement reforms to hiring protocols independently from government approval, and with a reporting framework that ensures it is subject to parliamentary scrutiny.

Parliament should ratify and pass a law ensuring the independence of the administrative courts. A draft of the law already exists and is under review by a parliamentary committee. This law should be free of loopholes that enable political interference in administrative decisions. Independent administrative courts should then pursue implementation of Article 95 Section B of the Constitution. A separate overarching judicial independence law drafted by civil society should support judicial independence across all branches of the judiciary.

The government should take action on existing recommendations to strengthen the regulatory environment required for privatisation of state-owned enterprises. This includes strong and independent sectoral regulators, a functioning civil service recruitment body, and a rebalanced recruitment of fixed-term staff and contractors. Once these are established, priority for privatisation should be given to the electricity sector, currently a major drain to state finances, and draft laws for an Energy Regulatory Authority (ERA) which already exist. An independent ERA must be empowered to oversee price setting and prevent cartel-like behaviour in the industry, while also ensuring an upgrade of the metering system to use smart meters across the network.

Senior ranking positions in the military should be reduced in line with existing organisational staffing plans. In the long term this will lower LAF personnel costs by reducing the highest paid salaries, benefits and pensions.

Editor’s Note: Badil would like to express our sincere thanks to the technical experts who provided inputs to this paper, with particular thanks to Lamia Moubayed, Sabine Hatem, and Oussama Safa.

[1] Bahout, J. (2016) “The Unravelling Of Lebanon’s Taif Agreement: Limits Of Sect-Based Power Sharing”, Carnegie Endowment For International Peace, www.carnegieEndowment.org/pubs

[2] Ibid.

[3] Shahda, E. A (2005) “The Role of the Civil Service Council in Reforming The Lebanese Bureaucracy”, Master’s Thesis, Notre-Dame University, Lebanon, online at http://ir.ndu.edu.lb:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/1439?show=full

[4] Ibid.

[5] Moubayyad Bissat, L (2018)“Why Civil Service Reform in an Inevitable Choice in times of crisis” Institut des Finances Basil Fuleihan, Lebanon, online at http://www.institutdesfinances.gov.lb/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/6-Why-Civil-Service-Reform-in-an-Inevitable-Choice-in-times-of-crisis-Lamia-Moubayed-Bissat.pdf

[6] Salloukh B. (2019) Taif and the Lebanese State: The Political Economy of a Very Sectarian Public Sector, Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 25:1, 43-60, DOI:10.1080/13537113.2019.1565177

[7] The Lebanese Council for Planning and Development, A Five Years Plan For Economic Development In Lebanon, Beirut; 1958 pp.339-341. In Ba’aklini, Abdo Iskandar, (1963) “The Civil Service Board in Lebanon”, American University of Beirut (Lebanon) ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2755087, online at https://www.proquest.com/openview/544a1c7cc6c30606d58e6cfa4ffa5729/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2026366&diss=y

[8] Shahda, E. A (2005) “The Role of the Civil Service Council in Reforming The Lebanese Bureaucracy”, Master’s Thesis, Notre-Dame University, Lebanon, online at http://ir.ndu.edu.lb:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/1439?show=full

[9] B Salloukh B. (2019) Taif and the Lebanese State: The Political Economy of a Very Sectarian Public Sector, Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 25:1, 43-60, DOI:10.1080/13537113.2019.1565177

[10] Faerlie C.F. (2017) ‘The Independent State and the State of Independence: Chehabism’s Challenge to Lebanese Democratic Stability’, Masters Thesis, Kings College London , https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/en/theses/the-independent-state-and-the-state-of-independence(a5b0fcb8-1077-4a1f-bc02-d0b41a313a14).html

[11] Daher, J. (2022) “Lebanon: How the Post War’s Political Economy Led to the Current Economic and Social Crisis” European University Institute , online at https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/73856/QM-01-22-031-EN-N.pdf

[12] Shahda E.A. (2016) “The Effects of Political Factors on Public Service Motivation: Evidence from the Lebanese Civil Service” Journal of Political Sciences & Public Affairs, Volume 4, Issue 4

[13] Salloukh B.(2019) Taif and the Lebanese State: The Political Economy of a Very Sectarian Public Sector, Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 25:1, 43-60, DOI:10.1080/13537113.2019.1565177

[14] Rose, S. (2019) “Lebanese MPs: 15,000 government employees hired illegally”, The National , February 28, 2019, online at https://www.thenationalnews.com/world/mena/lebanese-mps-15-000-government-employees-hired-illegally-1.831701

[15] Salloukh B. (2019) Taif and the Lebanese State: The Political Economy of a Very Sectarian Public Sector, Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 25:1, 43-60, DOI:10.1080/13537113.2019.1565177

[16] Salloukh B.(2019) Taif and the Lebanese State: The Political Economy of a Very Sectarian Public Sector, Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 25:1, 43-60, DOI:10.1080/13537113.2019.1565177

[17] Le Borgne, E. & Jacobs, T. J. (2016) “Lebanon – Promoting poverty reduction and shared prosperity : systematic country diagnostic “ Washington, D.C. World Bank Group.http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/951911467995104328/Lebanon-Promoting-poverty-reduction-and-shared-prosperity-systematic-country-diagnostic

[18] Ray, A. (2022) “No More Fun And Games: Saving Lebanon’s Education System Before It’s Too Late”, Badil, https://thebadil.com/in-depth/saving-lebanons-education-system/

[19] Le Borgne, E. & Jacobs, T. J. (2016) “Lebanon – Promoting poverty reduction and shared prosperity : systematic country diagnostic “ Washington, D.C. World Bank Group.

[20] Salloukh B. (2019) Taif and the Lebanese State: The Political Economy of a Very Sectarian Public Sector, Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 25:1, 43-60, DOI:10.1080/13537113.2019.1565177

[21] LBC (2019) ”Lebanon’s railway administration has 300 employees, but no railroad” Lebanese Broadcasting Corporation International, online at https://www.lbcgroup.tv/news/breaking-news/440237/lebanons-railway-administration-has-300-employees/en

[22] Interview with Oussama Safa, Chief of Section at United Nations Economic and Social Commission for West Asia, former General Director of Lebanese Centre for Policy Studies, March 29, 2023

[23] Interview with Sabine Hatem, Economist at the Institut des Finances Basil Fuleihan, Lebanon Ministry of Finance, March 28 2023

[24] Article 80 of Law No. 144 related to the general budget and supplementary budgets for 2019, obligated the government to conduct a comprehensive occupational survey on all public administrations and establishments dealing with personnel affairs (Civil Service Board and Central Inspection Bureau), provided that a copy of it shall be referred to the Parliament.

[25] Gherbal Initiative (2021) “The occupational survey: 92,000 personnel in public sector and 72 percent vacancies and 27,000 occupations conceal illegal contracting”, Gherbal Initiative, online at https://elgherbal.org/grains/ake7GCq81azdQ1FolzOE

[26] Interview with Sabine Hatem, Economist at the Institut des Finances Basil Fuleihan, Lebanon Ministry of Finance, March 28 2023

[27] Salloukh B. (2019) Taif and the Lebanese State: The Political Economy of a Very Sectarian Public Sector, Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 25:1, 43-60, DOI:10.1080/13537113.2019.1565177

[28] Ghoussaini and Wood (2021) ”Force for Funds: Saving Lebanon’s Army from Financial Collapse”, Triangle, online at https://www.thinktriangle.net/lebanon-army-financial-collapse/

[29] Gherbal Initiative (2021) “The occupational survey: 92,000 personnel in public sector and 72 percent vacancies and 27,000 occupations conceal illegal contracting”, Gherbal Initiative, online at https://elgherbal.org/grains/ake7GCq81azdQ1FolzOE

[30] Interview with Sabine Hatem, Economist at the Institut des Finances Basil Fuleihan, Lebanon Ministry of Finance, March 28 2023

[31] Salame, R. (2022) ”Lebanon’s Civil Servants Are Leaving in Droves, They Won’t Be Replaced Soon”, L’Orient Today, November 5 2022, https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1316973/lebanons-civil-servants-are-leaving-in-droves-they-arent-being-replaced-soon.html

[32] The Monthly ” Civil Servants to Get 38% – 144% Pay Raise” Monthly Magazine, online at https://monthlymagazine.com/article-desc_4506_

[33] Azour, R.R. (2013) “Personnel Cost In The Central Government An Analytical Review Of The Past Decade”, Bassil Fuleihan Institute Of Finance

[34] Interview with Lamia Moubayyad, President of the Bassil Fuleihan Institute of Finance, Lebanese Ministry of Finance

[35] World Bank (2022) “Lebanon Public Finance Report: Ponzi Finance?” World Bank Group online at https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/08/02/lebanon-s-ponzi-finance-scheme-has-caused-unprecedented-social-and-economic-pain-to-the-lebanese-people

[36] Salloukh B. (2019) Taif and the Lebanese State: The Political Economy of a Very Sectarian Public Sector, Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 25:1, 43-60, DOI:10.1080/13537113.2019.1565177

[37] Gherbal Initiative (2020) ‘Lebanese Ministries’ Staff Breakdown’, Gherbal Initiative Lebanon, online at https://elgherbal.org/reports/VB7uxN7Nilrk5B6W6vLs

[38] Interview with Sabine Hatem, Economist at the Institut des Finances Basil Fuleihan, Lebanon Ministry of Finance, March 28 2023

[39] Gherbal Institute (2021) ” The occupational survey: 92,000 personnel in public sector and 72% vacancies and 27,000 occupations conceal illegal contracting” Gherbal Institute, online at https://elgherbal.org/grains/ake7GCq81azdQ1FolzOE

[40] Interview with Sabine Hatem, economist at the Institute of Finance, Lebanon Ministry of Finance, March 28, 2023

[41] Interview with Sabine Hatem, economist at the Institute of Finance, Lebanon Ministry of Finance, March 28, 2023

[42] Schellen, T. (2017) “The administration’s missing cogs” Executive Magazine, February 14, 2017 https://www.executive-magazine.com/economics-policy/the-administrations-missing-cogs

[43] Moubayyad, L (2018) “Why Civil Service Reform in an Inevitable Choice in times of Crisis” , Institute of Finance, Ministry of Finance, Lebanon, online at http://www.institutdesfinances.gov.lb/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/6-Why-Civil-Service-Reform-in-an-Inevitable-Choice-in-times-of-crisis-Lamia-Moubayed-Bissat.pdf

[44] Interview with Oussama Safa, Chief of Section at United Nations Economic and Social Commission for West Asia, former General Director of Lebanese Centre for Policy Studies, March 29, 2023

[45] Halabi S (2010) ”Propping up the state”, Executive Magazine, https://www.executive-magazine.com/economics-policy/propping-up-the-state

[46] Arab Barometer (2019) “Arab Barometer V: Lebanon Country Report” Arab Barometer, online at https://www.arabbarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/lebanon-report-Public-Opinion-2019.pdf

[47] USAID (2019) ‘ USAID/Lebanon Citizen Perception Survey’, United States Agency for International Development, online at https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00X68X.pdf

[48] Ray, A. (2022) “No More Fun And Games: Saving Lebanon’s Education System Before It’s Too Late”, Badil, https://thebadil.com/in-depth/saving-lebanons-education-system/

[49] Shahda E.A. (2016) “The Effects of Political Factors on Public Service Motivation: Evidence from the Lebanese Civil Service” Journal of Political Sciences & Public Affairs, Volume 4, Issue 4

[50] Youth 4 Governance (2021) “From Crisis Management To Public Management: Civil Servants Perception of the Public Administration.” https://www.youth4governance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Public_Administration_Presentation.pdf

[51] Ray, A (2021) ”Breaking Point: The Collapse of Lebanon’s Water Sector, Triangle, online at https://www.thinktriangle.net/breaking-point-the-collapse-of-lebanons-water-sector/”

[52] IOF (2018) ”Why Civil Service Reform in an Inevitable Choice in times of crisis”, Institut des Finances Basil Fuleihan, Ministry of Finance, Lebanon, http://www.institutdesfinances.gov.lb/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/6-Why-Civil-Service-Reform-in-an-Inevitable-Choice-in-times-of-crisis-Lamia-Moubayed-Bissat.pdf

[53] Interview with Oussama Safa, Chief of Section at United Nations Economic and Social Commission for West Asia, former General Director of Lebanese Centre for Policy Studies, March 29, 2023

[54] Interview with development economist and civil service reform consultant Ola Sidani, March 24, 2023

[55] Interview with Oussama Safa, Chief of Section at United Nations Economic and Social Commission for West Asia, former General Director of Lebanese Centre for Policy Studies, March 29, 2023

[56] Central Inspection Bureau, Lebanon, https://www.cib.gov.lb/en/%D8%A5%D9%86%D8%B4%D9%80%D9%80%D8%A7%D8%A1-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AA%D9%81%D8%AA%D9%8A%D8%B4-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%B1%D9%83%D8%B2%D9%8A

[57] World Bank (2022) “Lebanon’s Ponzi Finance Scheme Has Caused Unprecedented Social and Economic Pain to the Lebanese People” World Bank Group, Press Release, August 3, 2022 online at https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/08/02/lebanon-s-ponzi-finance-scheme-has-caused-unprecedented-social-and-economic-pain-to-the-lebanese-people

[58] Interview with Faysal Makki, President of the Judges Association of Lebanon, March 7, 2023

[59] Chemaitilly, H. (2019) ‘Sectarian Politics and Public Service Provision: The Case of Electricité du Liban’, Afkar: The Undergraduate Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 1, no. 1 (Fall 2019): 33–47, King’s College London, online at https://afkarjournal.files.wordpress.com/2019/11/afkar-1.1-chemaitilly-sectarian-politics.pdf

[60] Salloukh, B. (2019) Taif and the Lebanese State: The Political Economy of a Very Sectarian Public Sector, Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 25:1, 43-60, DOI:10.1080/13537113.2019.1565177

[61] Salame R (2022) ” Lebanon’s civil servants are leaving in droves. They won’t be replaced soon”, L’Orient Today, November 5 2022 https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1316973/lebanons-civil-servants-are-leaving-in-droves-they-arent-being-replaced-soon.html

[62] TPI (2022) “The Policy Initiative – Lebanon’s discretionary spending favours public sector employees”, The Policy Initiative, online at https://www.thepolicyinitiative.org/article/details/193/lebanon percentE2 percent80 percent99s-discretionary-spending-favors-public-sector-employees

[63] https://www.omsar.gov.lb/Ministry/History

[64] ICJ (2022) ” Lebanon: Ensure the independence of the judiciary“, International Commission of Jurists, online at https://www.icj.org/lebanon-ensure-the-independence-of-the-judiciary/

[65] Legal Agenda (2022) ”The Key Discussions in the First Public Parliamentary Committee Meeting: Judicial Independence is a Public Matter Discussed Above – Not Underneath – the Table” Legal Agenda Lebanon, online at https://english.legal-agenda.com/the-key-discussions-in-the-first-public-parliamentary-committee-meeting-judicial-independence-is-a-public-matter-discussed-above-not-underneath-the-table/

[66] Interview with Faysal Makki, President of the Judges Association of Lebanon, March 7, 2023

[67] Ibid.

[68] MEED (2008) “Ziad Hayek on reforming Lebanon’s energy sector”, MEED Media, online at https://www.meed.com/ziad-hayek-on-reforming-lebanons-energy-sector/

[69] IOF (2021) “Briefing Note on SOEs in Lebanon, Institut des Finances Basil Fuleihan, online at http://www.institutdesfinances.gov.lb/publication/soes-in-lebanon/

[70] Interview with Ziad Hayek, former president of Lebanon’s Higher Council for Privatisation and Partnerships, Tuesday, March 14, 2023.

[71] Kostanian A (2021) ”Privatization of Lebanon’s Public Assets: No Miracle Solution to the Crisis”, Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs (IFI) at the American University of Beirut (AUB)

[72] Interview with Ziad Hayek, former President of the Higher Council For Privatisation, March 14, 2023

[73] Kostanian A (2021) ”Privatization of Lebanon’s Public Assets: No Miracle Solution to the Crisis”, Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs (IFI) at the American University of Beirut (AUB)

[74] IOF (2021) “Briefing Note on SOEs in Lebanon, Institut des Finances Basil Fuleihan, online at http://www.institutdesfinances.gov.lb/publication/soes-in-lebanon/

[75] Kikeri, Nellis, and Shirley, 1992, “Privatisation: The Lessons of Experience”, The World Bank, Washington, DC. p.2

[76] Kostanian A (2021) ”Privatization of Lebanon’s Public Assets: No Miracle Solution to the Crisis”, Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs (IFI) at the American University of Beirut (AUB)

[77] Interview with Ziad Hayek, former President of the Higher Council For Privatisation, March 14, 2023

[78] IOF (2021) “Briefing Note on SOEs in Lebanon, Institut des Finances Basil Fuleihan, online at http://www.institutdesfinances.gov.lb/publication/soes-in-lebanon/

[79] Kostanian A (2021) ”Privatization of Lebanon’s Public Assets: No Miracle Solution to the Crisis”, Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs (IFI) at the American University of Beirut (AUB)

[80] Interview with Ziad Hayek, former President of the Higher Council For Privatisation, March 14, 2023