Uncivil Lebanon

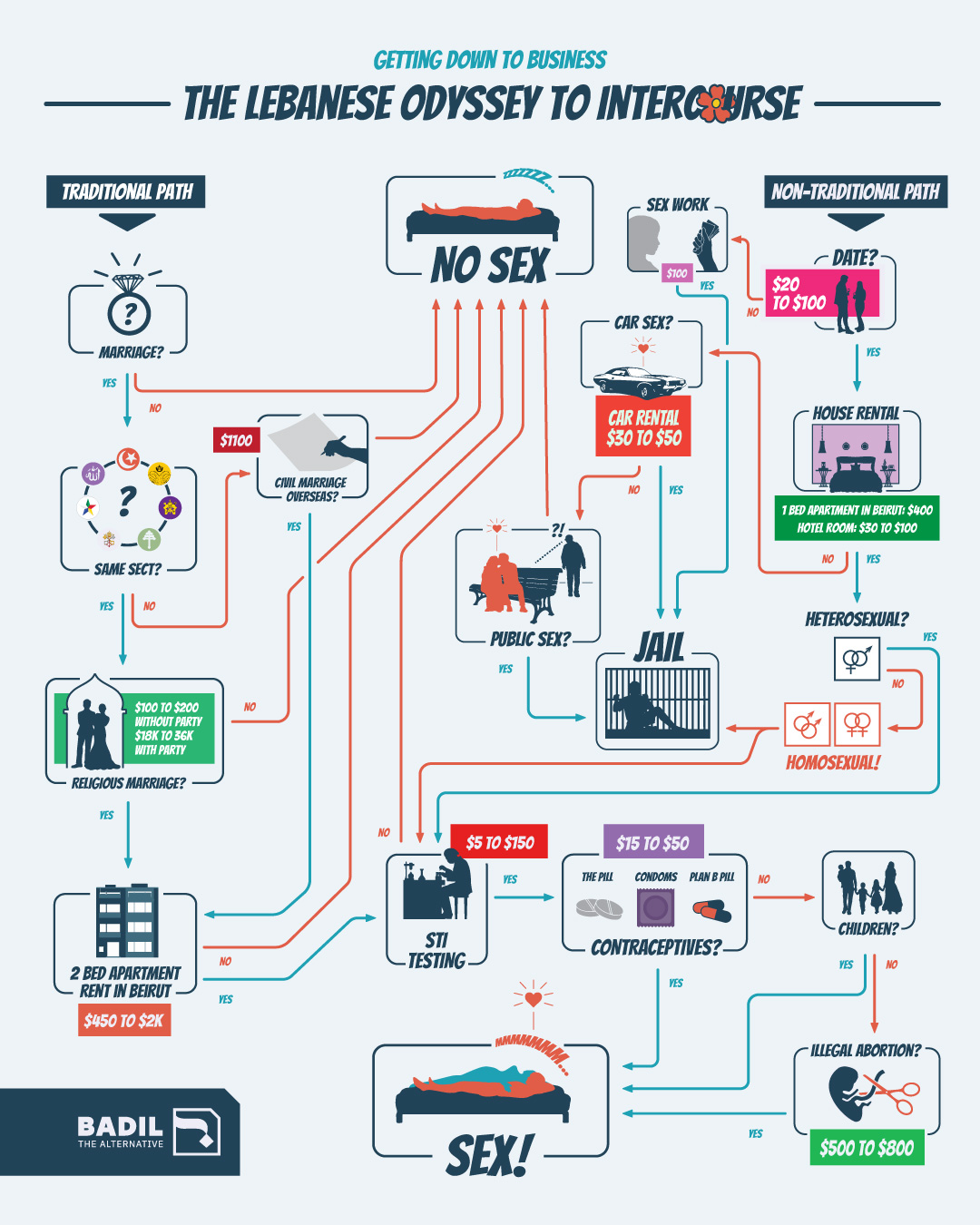

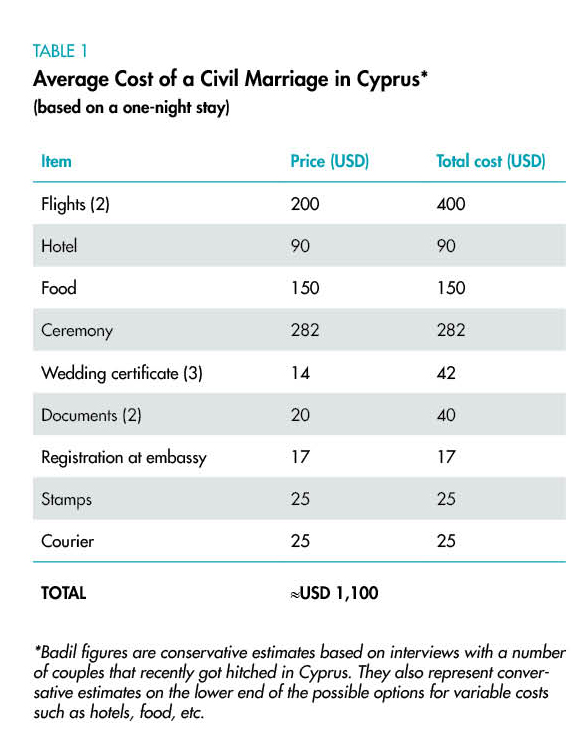

In July 2022, a Druze-Shiite couple residing in Lebanon found a way to have a civil marriage in the United States, when a judge in Utah united them in an online ceremony. Following the outbreak of the Covid pandemic, the state allowed for virtual marriage ceremonies, even for couples outside the country. [16]

Whether Lebanon will recognize the Utah marriage contract remains to be seen. If so, it would set a ground-breaking precedent on how to bypass the country’s archaic marriage arrangements, guarantee an equal standing between partners, and save young couples a considerable amount of money.

Legalizing civil marriage in Lebanon has been a topic of national debate since at least the 1950s. The debate took centre-stage during the October 2019 popular uprising. Yet religious authorities have always resisted change — which is not entirely surprising seeing that the 2018 state budget allocated religious courts with US$41.3 million, over quadruple the amount the Ministry of Environment was given.[17]

Legalizing civil marriage in Lebanon would not only offer both partners equal rights, but would also contribute to the economy, as couples would organize wedding parties in Lebanon rather than in Cyprus or Greece. Cyprus registers around 7,000 marriages a year, which contributes to an estimated US$1.1 million to the Cypriot national economy.

Costly breakup

The link between economic status and sexual freedom also applies to divorce, which often represents a financial and legal barrier many couples cannot overcome. The lack of a national personal status code allows for great variations when it comes to divorce.

For some women, it is relatively easy, while for others it becomes a strategic game of chess that can take years. Generally, sectarian barriers make it much harder for a woman to get out of an unwanted marriage than a man. Cases regarding marital support and child custody are particularly tricky.

In 2020, Parliament passed a bill criminalizing sexual harassment and expanding the scope of a law penalizing domestic violence. [18] While a welcome step in the right direction, the bill has been criticized for failing to protect victims of sexual violence. More so, the Lebanese penal code still allows for a husband to avoid punishment for marital rape if he can show a valid marital contract.

The cost of getting a divorce varies across the different sects. The main expense tends to be hiring a lawyer, given the couple in question does not agree on the divorce terms. In Christian courts, although lawyers are required to sign a contract stipulating legal fees cannot exceed US$5,000, the bill at times can amount up to US$25,000. Unofficial costs include bribes to move the divorce case forward.

Sunni, Shia, and Druze laws offer men an absolute right to divorce, while women only have that right under certain conditions. For Christians, it is difficult for both men and women. Most of them will ultimately end up in a religious court. Even if both partners agree to have a divorce, the religious authority has the ultimate decision. At times, the case may be transferred all the way to the Vatican to be resolved.

The Crime of “Unnatural Sex”

While the state leaves marriage and divorce proceedings to the country’s religious courts, it does involve itself in the policing of non-normative sexual behaviours, adding further layers of oppression, especially for the LGBTQ+ community. Queer people can be prosecuted under Article 534 of the Lebanese Penal Code, which does not specifically criminalize gay sex but prohibits “sexual intercourse against nature.” [19]

Recent rulings have set a precedent for decriminalization. There have been at least six cases, in which the judge ruled that “unnatural relations” do not include same-sex relations.[20] However, as long as Article 534 exists it can be used to target and prosecute queer people.

The latest incident of state-sanctioned violence came in June, widely known as Pride Month, when Interior Minister Bassam Mawlawi wrote a letter banning assemblies that “promote homosexuality.” The minister sent the letter to the Internal Security Forces (ISF), which promptly raided one of the few free safe spaces for queer people in Beirut.

There are a handful of safe spaces in Beirut where queer people can meet openly. Many queer spaces have either closed due to the economic crisis, or have been damaged by the Beirut port explosion, raising concerns that these spaces may never recover. Of the few remaining, most are bars or nightclubs with high entry costs. As a result, such privileges and pleasures remain out of reach for most queer Lebanese. Going on a date in a free public space may not be an option for some, out of fear of being outed (i.e., having one’s sexual orientation revealed publicly).

Another way for people to meet is through online dating apps such as Tinder, Grindr, or Bumble. However, for LGBTQ+ people this too can be risky due to the same reasons as cited above. Regarding Grindr, Lebanon’s Ministry of Telecommunications banned the gay dating app in January 2019, which constituted a state-mandated step backwards for LGBTQ+ rights. [21]

Apart from that, people need a smartphone and internet access to access online dating apps, all of which are today priced in dollars. Telecommunication tariffs sharply increased in July 2022 when the Council of Ministers changed the pricing structure in their final session before entering caretaker mode.

Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare

Access to Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (SRH) is a fundamental right, essential to a person’s well-being. About half of the Lebanese have health insurance (public or private), yet even for those insured, there is an alarming lack of coverage. [22] Private hospitals, since May 2022, have started to only accept patients able to pay in dollars. Insurance companies have followed suit, with all insurance packages now priced in US dollars. [23]

Women and the LGBTQ+ community face significantly more barriers in accessing SRH. For example, many LGBTQ+ individuals are reluctant to open-up to healthcare professionals about their sex life out of fear of discrimination, being outed, or blackmailed.

“After receiving a HIV+ diagnoses, some patients deny their status and treatment,” said a medical professional who wished to remain anonymous. Although HIV treatment is covered by the National AIDS Control Program, patients fear the socio-economic repercussions if their status would be revealed.

Antoine* (pseudonym) described to Badil his experience of being diagnosed with HIV and the secretive process of getting treatment. Having been tested positive by a local non-governmental organization (NGO), he was sent to a doctor for additional testing. The latter only wanted to see him after closing hours.

“Only the secretary and doctor were still in the office. It felt as if I was doing something illegal,” Antoine said.

Antoine was then sent to the Ministry of Health where he used a backdoor entrance to receive a three-month supply of antiretroviral (ARV) medication. Antoine explained to Badil that he is worried the ministry will run out of funding for the drug. A one-month supply of ARV once retailed at over US$1,200, but with generic versions can averages at US$100. [24]

However, according to Nadia Badran, Executive Director of the Society for Inclusion and Development in Communities (SIDC), which works with people living with HIV, there is little risk that the Ministry of Public Health’s National AIDS Control Program loses funding, as the “[antiretroviral] medications are funded by UN agencies.” In other words, the programmes will run until donor money runs out.

Price Hikes in SRH

Having safer sex in Lebanon has become even more inaccessible since the pre-2019 crisis days. All of the medical costs associated with safer sex (including STI testing, treatment, and contraceptives) have seen significant price hikes in recent years and are increasingly out of reach for most (see Table 2).

Prices of oral contraceptives have increased by nearly 750% since 2019. [25] The price of one well-known birth control pill (Yaz) went up from LBP 21,000 to 480,000. The prices of trusted condom brands also skyrocketed (see Table 3).

The increased inaccessibility of contraceptives has had an impact on unwanted pregnancies and led to a rise in abortions, according to Faysal El-Kak, Senior Lecturer at the Faculty of Health Sciences at the American University of Beirut (AUB) and Clinical Associate, Department of Obstetrics Gynecology at AUB Medical Center, as quoted in L’Orient Today. [26]

“The compounded crisis in Lebanon has affected almost all facets of life, including women’s and adolescent health, and in specific reproductive health,” El-Kak said in an interview with Badil. He also explained that for the last three years, “Lebanon witnessed an interruption of contraceptive supplies […] that affected access and affordability in the face of expensive pregnancy care.” Amid economic turmoil, “pregnancy intentions change,” explained El-Kak.

Unless the mother’s life is in danger, abortions in Lebanon are illegal and are not covered by insurance. Abortions still occur under the table and can range from US$500-700 , at the minimum.

Conclusion

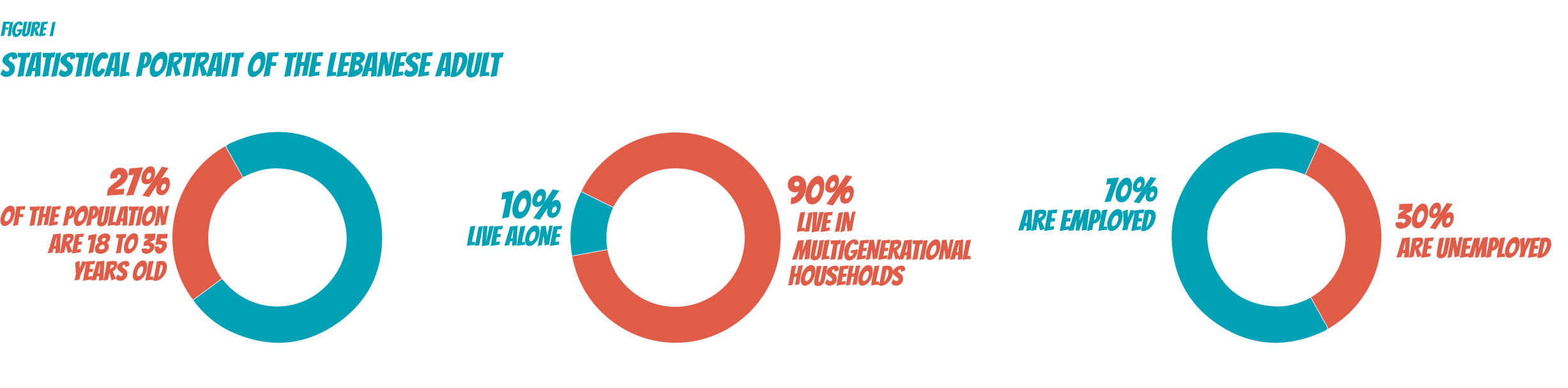

Everyone has the right to sexual freedom and to express themselves however they choose to. However, socio-economic status, as well as societal norms and values greatly influence people’s ability to have sex. There is no doubt that poverty closes many doors, and sex is no exception.

The recent collapse of the Lebanese economy has had crushing consequences for people to form meaningful relationships and sexually express themselves. Constrained by a decades-long lack of social housing polices, lack of personal status laws, archaic penal codes, and underfunded SRH, Lebanon’s residents simply cannot afford the material resources needed to have safer sex.

Most young Lebanese cannot afford to buy a home or rent an apartment and, hence, lack access to much needed privacy.

The conventional route to sex has always been marriage, yet this too is often a very costly affair, certainly when a wedding party is involved. Lebanon’s archaic personal status laws only allow for a religious marriage between two parties of the same sect.

For a civil marriage the road leads abroad, which immediately entails extra costs for plane tickets and hotels. Gay marriage does not exist in Lebanon. Worse, the Lebanese Penal Code until this very day criminalizes “unnatural sex,” which can be used to prosecute same-sex relations.

As prices for contraceptives have skyrocketed, and many hospitals and insurance companies only accept payment in dollars, safer sex too is increasingly out of the reach for most Lebanese. One thing is certain: economic and sexual justice are intimately linked and the current financial crisis is aggravating both. Yet instead of opening up the sexual space, the state and the clergy who stand with them think it’s their job to interfere in the most personal of Lebanese affairs. It’s not. It’s in fact time to get the clergy and the state to get out of Lebanon’s bedrooms, and back into the halls of prayer and government.

Recommendations

To promote equal standing among partners and access to safer sex, state and clerical involvement in sexual affairs will need a complete shakeup.

First and foremost, for those who chose it, a civil personal status law, rather than religious edict, should dictate the rights of all Lebanese regarding marriage, divorce, and inheritance. Advocates of an obligatory civil personal status law tend to forget the legal and social implications of such a move. The freedom to choose the regime under which one gets married should also apply to those who wish to follow faith-based rulings.

Despite outcries from the religious authorities, all public and private schools should immediately re-introduce sex education, starting in the 6th grade (students aged 12 to 14). Health professionals too should receive training on safe and consensual sexual behaviour, as well as on topics related to sexuality and gender identity.

Too often, sexual violence goes unreported and unpunished, creating a culture of impunity for the perpetrators and fear for the victims. As a result, informal avenues such as family and community leaders are forced to intervene because of the state’s lack of enforcement. If the recent uptick in sexual violence is anything to go by, the entire support system for victims needs revamping — from safe referrals and shelters to training for security forces on how to deal with sexual assault cases.

The provision of affordable (even free) contraceptive options should be made a priority. This needs to include contraceptives, morning after pills and abortions, as well as access to counselling for planned parenthood. Obviously, the legal right to abortion should be placed high on the agenda by the progressive movement, as it is every woman’s right to decide over her own body.

Nothing less than an immediate and outright appeal of articles 534 and 523 of the Penal Code will do, as they are used to criminalize members of the LGBTQ+ community and sex workers.

In addition, the labour law needs to include measures to protect anyone from being fired on grounds of sexuality or gender identity, as well as threats, blackmail, and other forms of discrimination. Progressive forces should champion the right to “own” one’s body and promote sexual freedom and expression in legal texts, including the constitution.

Access to housing is always intricately connected to sexual freedom and expression, as well as the constitutional right to privacy. With no public housing policy in sight, the current situation characterized by a lack of access to affordable housing will likely remain. Urgent action that ought to be taken include the provision of housing for marginalized groups. On the longer term, taxes on empty residences and the application of the rental law could change the market’s supply-demand dynamics and make housing more affordable.

[1] Saul McLeod, 2007, “Maslow’s hierarchy of needs,” online at: https://canadacollege.edu/dreamers/docs/Maslows-Hierarchy-of-Needs.pdf

[2] Relief Web, 2021, “Multidimensional poverty in Lebanon,” Online at: https://reliefweb.int/report/lebanon/multidimensional-poverty-lebanon-2019-2021-painful-reality-and-uncertain-prospects

[3] SIDA, 2010, “Poverty and Sexuality,” online at: https://www.sxpolitics.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/sida-study-of-poverty-and-sexuality1.pdf

[4] ILO, 2022, “Lebanon and the ILO release up-to-date data on national labour market,” online at: https://www.ilo.org/beirut/media-centre/news/WCMS_844831/lang–en/index.htm

[5] Beirut Urban Lab, “A City For Sale,” online at: https://www.beiruturbanlab.com/en/Details/612/beirut%E2%80%99s-residential-fabric

[6] Irbid.

[7] Helem, 2021, “LGBTQ+ Rights Violations Report,” Online at: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1CkHc3gK4n8Apa1uV-xBC5seTzJeB7Uir/view?usp=sharing

[8] Central Administration of Statistics, 2020, “Labour Force and Household Living Conditions Survey,” online at: http://www.cas.gov.lb/images/Publications/Labour%20Force%20and%20Household%20Living%20Conditions%20Survey%202018-2019.pdf

[9] Helem, 2021, “LGBTQ+ Rights Violations Report,” Online at: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1CkHc3gK4n8Apa1uV-xBC5seTzJeB7Uir/view?usp=sharing

[10] Beirut Today, Maguie Hamzeh, 2021, ”Queer and homeless: LGBTQ+ housing issues after the Beirut blast,” Online at: https://beirut-today.com/2021/05/20/queer-and-homeless-lgbtq-housing-issues-beirut-blast/

[11]UNDP, 2018, ” Lebanon’s bid toward low-carbon mobility,” online at: https://www.undp.org/lebanon/news/lebanons-bid-toward-low-carbon-mobility

[12] Sulome Anderson, Foreign Press, 2012, ” Sex for Sale in Beirut,” online at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2012/02/09/sex-for-sale-in-beirut/#:~:text=Although%20prostitution%20is%20technically%20legal,super%20nightclubs%20is%20nominally%20illegal.

[13] Ghada Jabbour, KAFA, 2014, “Exploring The Demand For Prostitution,” Online at: https://kafa.org.lb/sites/default/files/2019-01/PRpdf-69-635469857409407867.pdf

[14] Ibid.

[15] Women Economic Empowerment Portal, 2016, ”850 civil marriages of Lebanese in Cyprus each year,” online at: https://www.weeportal-lb.org/news/850-civil-marriages-lebanese-cyprus-each-year

[16] Anne-Marie EL HAGE, L’Orient Today, 2022, ”Online civil marriage ceremonies, a new pressure tactic for Lebanese couples,” online at: https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1306143/online-civil-marriage-ceremony-a-new-pressure-tactic-for-lebanese-couples.html

[17] Gherbal Initiative, 2019, ”Amounts allocated in millions of dollars according to the 2018 budget,” online at: https://www.instagram.com/p/BuD7brUg3fu/?igshid=YmMyMTA2M2Y%3D

[18] Al Arabiye News, 2020, ” Lebanon passes law criminalizing sexual harassment, amends domestic violence law,” online at: https://english.alarabiya.net/News/middle-east/2020/12/21/Lebanon-passes-law-criminalizing-sexual-harassment-amends-domestic-violence-law

[19] Art. 534, of the Lebanese penal code.

[20] Proud Lebanon, 2017, ”The LGBTI community in Lebanon,” online at: http://proudlebanon.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/INT_CAT_CSS_LBN_26954_E.pdf

[21] Amnesty International, 2019, ”Lebanon: Ban on gay dating app Grindr a blow for sexual rights and freedom,” online at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/press-release/2019/05/lebanon-ban-on-gay-dating-app-grindr-a-blow-for-sexual-rights-and-freedom/

[22] Clotilde Marquis, 2021, “2019-2021 : Le système de santé libanais à l’épreuve de la crise économique », Chamber of Commerce Industry and Agriculture, online at : https://ccib.org.lb/uploads/60e2b67ed591b.pdf

[23] Shaya Laughlin, Guy Saad, Triangle, 2021, ”Nowhere To Heal: The Growing Luxury Of Medical Cover In Lebanon,” Online at: https://www.thinktriangle.net/medical-cover-in-lebanon/#_edn1

[24] UNAIDS, 2021, ”Big drops in the cost of antiretroviral medicines, but COVID-19 threatens further reductions”, online at: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/featurestories/2021/may/20210503_cost-of-antiretroviral-medicines

[25] Tala Ramadan, 16 December 2021, ”Women in Lebanon struggle with reproductive rights as birth control pills become unaffordable and abortion remains illegal”, L’Orient Today, online at: https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1284967/women-in-lebanon-struggle-with-reproductive-rights-as-birth-control-pills-become-unaffordable-and-abortion-remains-illegal.html

[26] Ibid.

[27] UNFPA, 2020, ” 3eib and Marriage: Navigating Comprehensive Sexuality Education in the Arab Region,” https://arabstates.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/situational_analysis_final_for_web.pdf

[28] BioMed Central, 2021, “Assessment of sexual and reproductive health knowledge and awareness among single unmarried women living in Lebanon: a cross-sectional study,” online at: https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-021-01079-x