Executive summary

In September 2021, the newly appointed Mikati government’s ministerial plan committed to shifting Lebanon towards a more productive economy. Two years ago, it seemed far-fetched that a Lebanese billionaire like Najib Mikati, as the country’s prime minister, would advocate for investment in sectors like agriculture and industry.

Since the civil war, Lebanese authorities have presided over a flimsy unproductive economic model permitting elites to indulge in rent-seeking activities. Oriented around a service-led economy, crony capitalism flourished at the expense of ordinary Lebanese, who did not share in profits generated from uncompetitive markets.

Instead of promoting agricultural and industrial production, Lebanon relied overwhelmingly on importing products from overseas – an affordable, easy option made possible by the wildly overvalued Lebanese Lira. This reckless economic strategy imploded spectacularly in October 2019, when Lebanon entered one of the most severe financial crises in recorded history. The Lebanese Lira, which has lost up to 90 percent of its value, can no longer purchase the same imports that once papered over the lack of Lebanese-made goods.

Managed correctly, Lebanon can reap huge rewards from shifting to a more productive economy. Key productive sectors – ranging from high-value crops to pharmaceuticals and creative consumer-facing products – can drastically improve Lebanon’s outlook from at least three key perspectives. Workers stand to benefit from more plentiful, sustainable jobs; aspiring entrepreneurs can be rewarded for innovation and willingness to take commercial risks; and the environment will find reprieve from sustainable agriculture and manufacturing leading the country’s long-overdue green transition.

Unfortunately, however, the potential for exploitation already lurks within Lebanon’s productive sectors. The agriculture industry relies overwhelmingly on cheap Syrian labour, cartels control markets for essential inputs, and farmers lack social protections for their increasingly precarious livelihoods.

Uncompetitive behavior similarly bedevils the manufacturing sector, as new entrants struggle to compete with politically connected firms that enjoy well-established, protected market shares. As ever in Lebanon, elites stand ready to bend any significant economic developments to their own selfish ends.

Accordingly, this economic reorientation demands careful, long-term planning by state and non-state actors alike. The bankrupt government, which cannot provide direct investment for the transition, should focus on regulatory reforms and enforcement mechanisms for laws covering labour, fair market competition, and environmental protection. Separately, non-governmental stakeholders can take immediate action by providing technical assistance for adopting green technology, empowering workers and vulnerable groups, and competitive business practices.

Lebanon’s financial crisis presents an opportunity for revolutionary, productive change. Yet, without a determined fightback, the country’s rapacious elites will merely switch their bankers’ suits for farmers’ overalls and continue to hold the economy hostage.

What Is A Productive Economy Shift?

A switch to a productive economy occurs when a country concentrates resources in sectors like agriculture and industry, which produce goods locally. If managed effectively, a productive switch can tackle socio-economic problems like import dependence and high unemployment rates. Such a change requires long-term structural reforms.

Without state intervention, the economic crisis has already forced many Lebanese people to accept the pressing need for a productive shift. In a functioning country, such a transition would require government funding and tax incentives for farms and factories, as well as better training opportunities and improved infrastructure. In Lebanon, a lack of available investment remains the biggest obstacle to growing the agriculture and industry sectors.

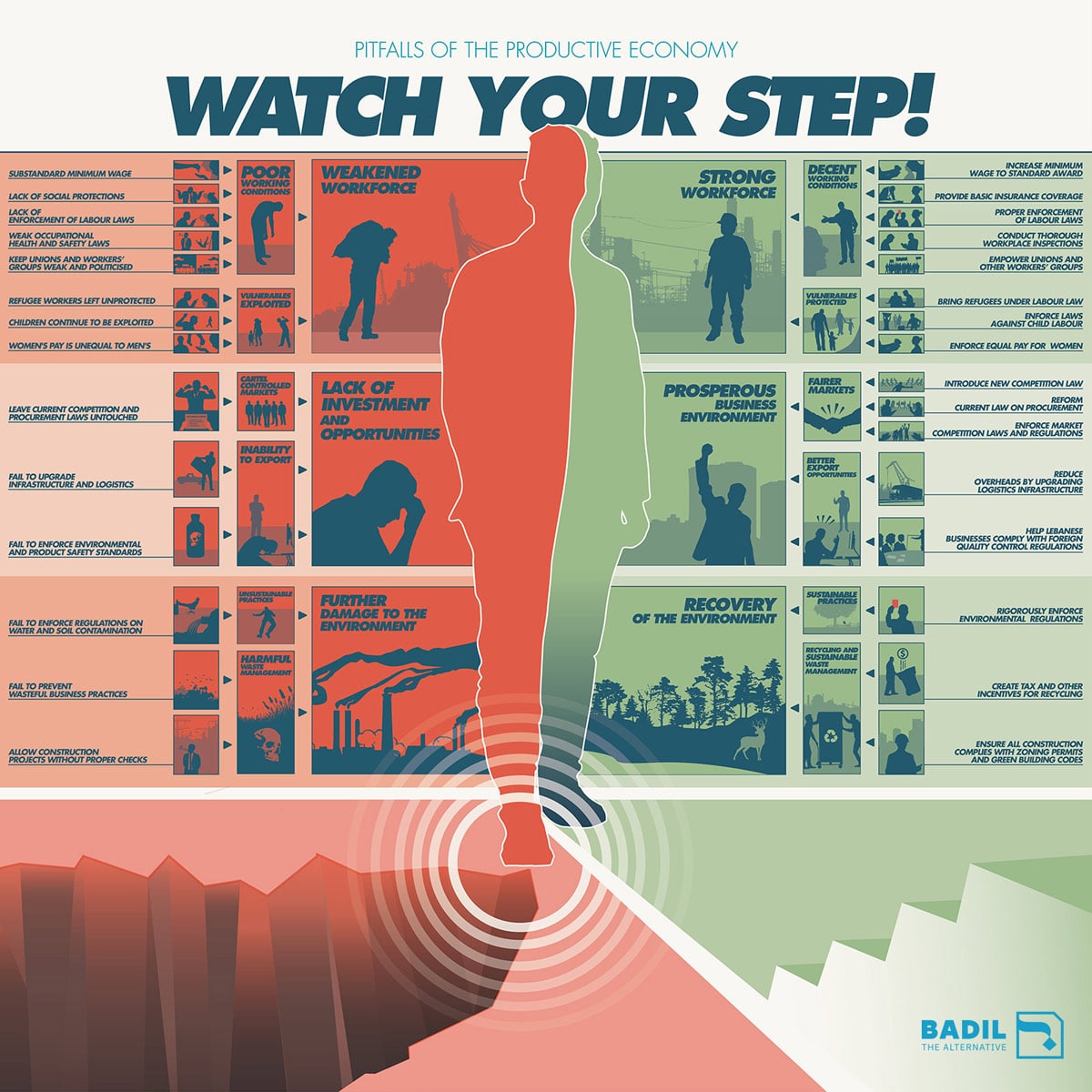

THE RISKS OF FALLING

Level 1: The Workers

Theoretically Lebanese workers would benefit greatly from the country moving away from a service-based economy. Productive sectors should be creating more jobs than they do at present. Many Lebanese industries have lain dormant for decades, performing far below their potential rate of job creation. For example, Lebanese pharmaceutical manufacturers have sufficient technical capacity to satisfy local demand for generic medications; nevertheless, due to consumer preferences for foreign-made drugs, the sector only claims a 21% share of the domestic generics market.[1] For its part, a more productive recycling industry could supply raw materials to Lebanese manufacturers and even export recyclables to foreign markets. Estimates indicate that recycling businesses could create 5,000 new jobs by 2025 if Lebanon participated in a comprehensive regional programme for recycling.[2] Importantly, it would often be unskilled workers who benefit from such new livelihood opportunities, ameliorating the worst impacts of the current crisis.

The Lebanese Lira’s devaluation means that many agricultural and industrial enterprises have more competitive export offerings – and therefore could receive payments in foreign currency – than previously. As one example, Lebanese wines have already become affordable in Western European markets, even after import duties are applied. With proper wage and work condition regulations, workers stand to benefit from their employer’s increased prosperity. Already, a considerable number of Lebanese food companies provide their direct employees with fair wages and social protection coverage. Such equitable employment structures are essential to arrest Lebanon’s alarming spike in poverty rates and promote sustainable, inclusive development.

At present, however, both agriculture and industry need drastic reforms and regulation of employers for workers to realise these potential benefits. Lebanon’s productive sectors currently rely on providing poor working conditions – with scant legal guarantees and social protections – and exploiting vulnerable communities to maximise profits. These practices risk spoiling the chance for everyday workers getting a fair deal in Lebanon’s productive sectors.

Pitfall 1: Poor Working Conditions

Most workers in Lebanon’s productive sectors do not receive a decent living wage. Even before the economic crisis, the minimum wage (around LL 675,000) was inadequate and could not keep a family of four above the poverty line.[3] To make matters worse, there is poor enforcement of the minimum wage which has not been updated to reflect rising costs of living. Today, the market value of the minimum wage hovers at around $US32 per month – barely enough to fill a medium-sized car with fuel.[4] In reality, most agricultural workers do not even receive this paltry salary, given that they work informally and accept payment below the minimum wage. A person working in manufacturing in Lebanon earns around LL 1,560,000 per month but salaries vary greatly across the sector depending on the position.[5]