Lebanon’s electricity woes can be fixed. Since the enactment of a law establishing an electricity sector regulator twenty years ago, however, successive ministers and governments have had different priorities. Today, the current caretaker Minister of Energy and Water, Walid Fayyad, is carrying the torch.

In place of spearheading badly needed and technically feasible reforms, Fayyad’s top agenda item since taking office in 2021 has been maintaining vested political interests within Électricité du Liban (EDL), the public power provider.

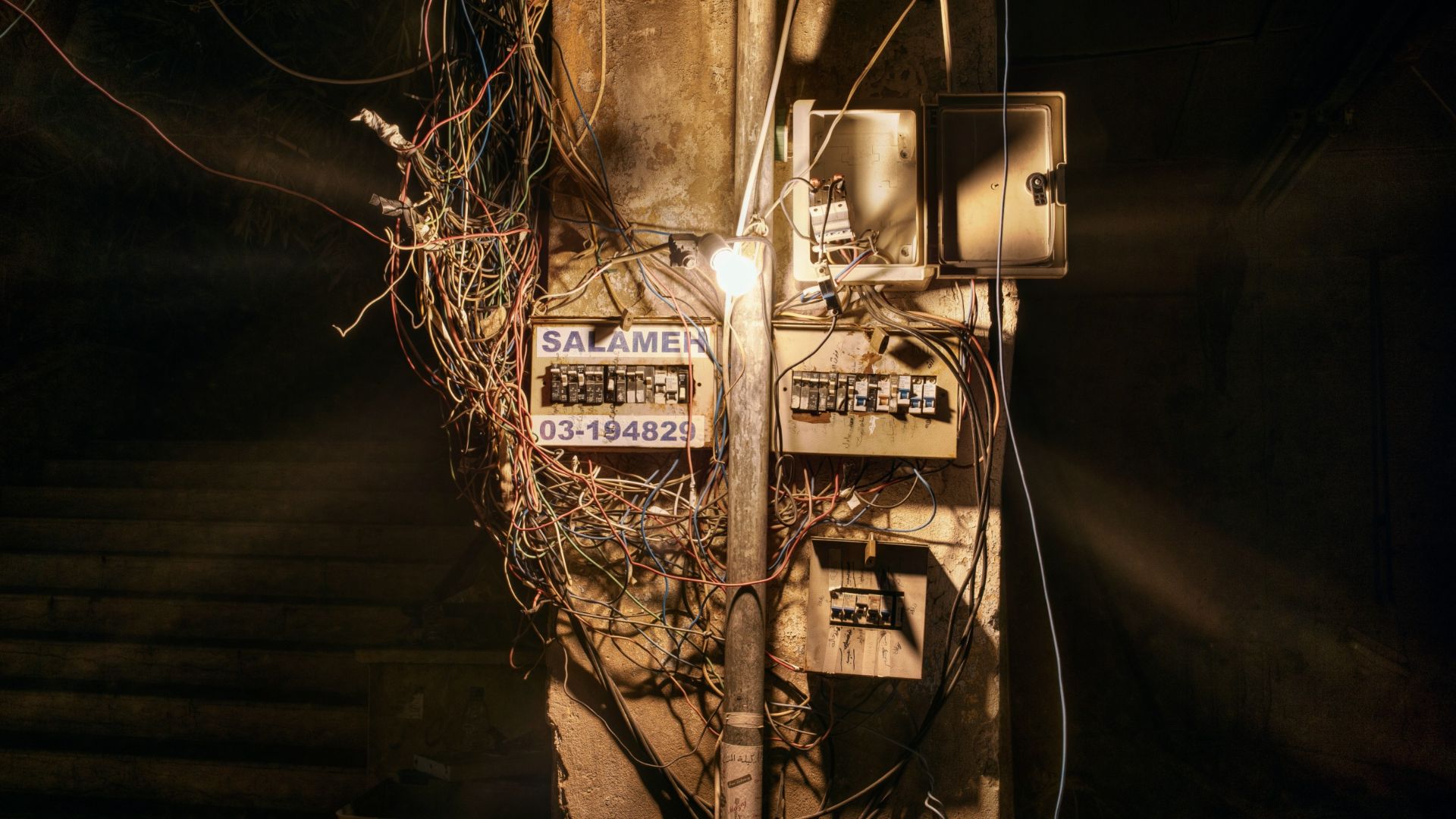

The result? EDL can hardly keep a lightbulb on for more than a couple hours in any given neighbourhood. This has forced Lebanon’s population to depend on an unlicensed, predatory, private generator cartel that has entrenched its power over the market and made sectoral reforms even harder to pursue.

To be fair, the problems predate Fayyad’s time in office, as few would ever have mistaken EDL for a high-functioning institution. Since the crisis began, however, Lebanon has experienced the near-complete collapse of its national electricity provider. As much as 90 percent of national power consumption is now provided by private generator owners, commonly referred to as the “generator mafia”. This has had profound impacts on people’s health and wealth.

In 2020, the World Bank briefly raised hopes of a reprieve for the energy sector with a gas and electricity deal it arranged between Egypt, Jordan, and Lebanon. Among the conditions for bank funding was an independent audit of EDL, and the establishment of an Electricity Regulatory Authority (ERA). Neither was carried out under the previous energy minister Raymond Ghajar and Lebanon doesn’t look to be any luckier under Fayyad. The independent audit of EDL is still pending, awaiting parliamentary approval, despite a local firm winning the tender over a year ago.

Regarding the ERA, it is an entity that was first stipulated by law as far back as 2002. It is meant to be governed by a five-person board and have the authority to set electricity tariffs and oversee any privatisation of Lebanon’s electricity sector. Despite issues in its foundations – including the power of the Council of Ministers to set board members’ salaries in consultation with the energy minister – the body offers a semblance of organisation to the sector.

Successive administrations since then have nonetheless left the authority totally unimplemented. In its two-decades absence, the energy ministry has been able to slowly appropriate the ERA’s mandate through a series of legislative measures.

Political interests vied for influence over the board’s ultimate composition as calls for the ERA’s establishment grew over the past decade. This included the efforts of the Free Patriotic Movement (FPM) to have a six-person board, closely mirroring the governance structure of the Lebanese Petroleum Administration, an entity widely considered dysfunctional.

FPM-nominated Fayyad supported these amendments in his revamped Electricity Reform Plan. Further amendments include the ERA requiring an absolute majority for board decisions, the chairman to cast the deciding vote in the event of a tie, and the Council of Ministers to arbitrate in instances where the ERA board and the energy minister disagree. This effectively creates layered defence against the regulator being able exercise its authority and implement its decisions. Other suggested FPM legal amendments since 2012, though not adopted, included changing the ERA to a simple consultative body.

In making gestures to fulfilling the World Bank criteria, Fayyad’s ministry issued a policy statement in March 2022 promising “the orderly transfer of authority to a fully functioning ERA (by the end of 2023)”. This deadline looks more and more unlikely. The application process leading to the approval of ERA board members by the Council of Ministers should have taken 8 weeks following its activation in December 2022, according to the Ministry’s Implementation Timetable. It is on track to take almost five times that.

The minister has extended the application window twice, citing a lack of qualified applicants. The exhaustive job criterion ostensibly suggests the importance of expertise and experience in the ministry’s consideration of ERA board candidates. Certainly, a hastily established, under-qualified regulatory board would only trap EDL further into its spiral of dysfunctionality.

The ministry assured, in a December 2022 document, that “fairness, objectivity, and due procedure” are the bedrock of the ERA implementation process. There is, however, another, unspoken qualification for the job: securing the backing of Lebanon’s political elite. If the 2020 appointment process for the EDL board of directors offers a blueprint – condemned by many as a sectarian carve up – competency will always come second to sectarian-political loyalty.

Fayyad, speaking with The Alternative earlier this year, claimed that in simply activating the application process to fill seats on the ERA board of directors, he had fulfilled the World Bank’s condition. The bank apparently disagreed, with electricity sector experts telling The Alternative that the international institution is backing away from its proposed deal, deeming it too risky.

Indeed, in place of lasting, tangible reforms, Fayyad’s tenure has been marked by band-aid solutions and failed policy shifts.

Fayyad secured another treasury advance of US$116 million to keep EDL running in January 2023. At the time the minister admitted this was an interim solution as he pursued an ill-fated plan to balance the books and increase public power provision to four hours per day.

This involved a tariff hike for state-provided electricity, introduced at the end of 2022. Despite assertions that increasing the pricing of electricity provision meant “cost recovery will be reached from day one” in a previous interview with The Alternative, Fayyad has since admitted his plan shorted out.

The main problem is that state electricity providers should first provide a steady supply of electricity to subscribers before increasing in tariffs, according to research by the IMF. A long-awaited audit of EDL would also likely have identified flaws in the minister’s plan, in particular its inability to sufficiently collect power bills from customers. Institutional reforms, involving overhauls in governance and ownership models, would have been far more likely to enable the electricity provider to attempt to break-even. These, however, would have seen the minister’s authority over the sector significantly diminish.

Having failed to meet the conditions of World Bank plan, and after seeing his own reform initiative fall flat, Fayyad sought to proclaim success by announcing a series of fuel agreements with Iraq in March 2023. The deal aims to prop up the country’s electricity sector through an immediate increase in fuel to a handful of power plants. Unlike the World Bank’s requirements, the deal neatly side steps investigating the systemic issues that enabled the sector to spiral into crisis in the first place.

Notably, Fayyad’s failed tariff hike and the Iraqi oil deal would have come under the ERA’s remit, or at the very least been overseen by the entity, had it been operational. In its absence both have been pushed through by the Ministry with little to no scrutiny.

We are thus very much left in the dark as to whether there will ever be an empowered electricity regulator – a circumstance Lebanon has become all too familiar with.