Taking a toll

The professional caregiver exodus could scarcely have come at a worse time, even in Lebanon’s tumultuous modern history.

“Of course, a lot of people are suffering tremendously from the political and economic situation,” said Aziz. “You feel like people are already at their last straw.”

While the government fails to provide comprehensive data on mental health, recent statistics from several NGOs underscore the gravity of Lebanon’s current predicament. Lebanese organization Embrace, which operates the national emotional support and suicide hotline, reported a 275% increase in callers since 2019, when the economic crisis began in earnest. Alarmingly, deteriorating conditions have weighed heavily on young Lebanese – about 60% of Embrace’s callers are aged 35 or below.

According to Embrace, the Beirut Port explosion only compounded mental health issues. Soon after the blast, a survey of Beirut residents found that 83% of respondents felt sad almost every day, 78% felt anxious or worried, and 84% felt sensitive to loud noises and dangers.

And now, with access to mental health services evaporating, victims have turned to negative coping strategies. Skoun, a local NGO that runs a free addiction rehabilitation center, has recorded a strong increase in demand in recent years. In 2019, Skoun admitted about 450 people for addiction; this figure had jumped by 33% by the end of 2021. Skoun expects these numbers to increase in 2022, as the organization has already extended the current waiting list for treatment.

A longstanding problem

The government cannot blame Lebanon’s mental health catastrophe on bad luck. Rather, the sector has been mismanaged for decades, leaving vital services hopelessly exposed to the country’s unprecedented economic crisis.

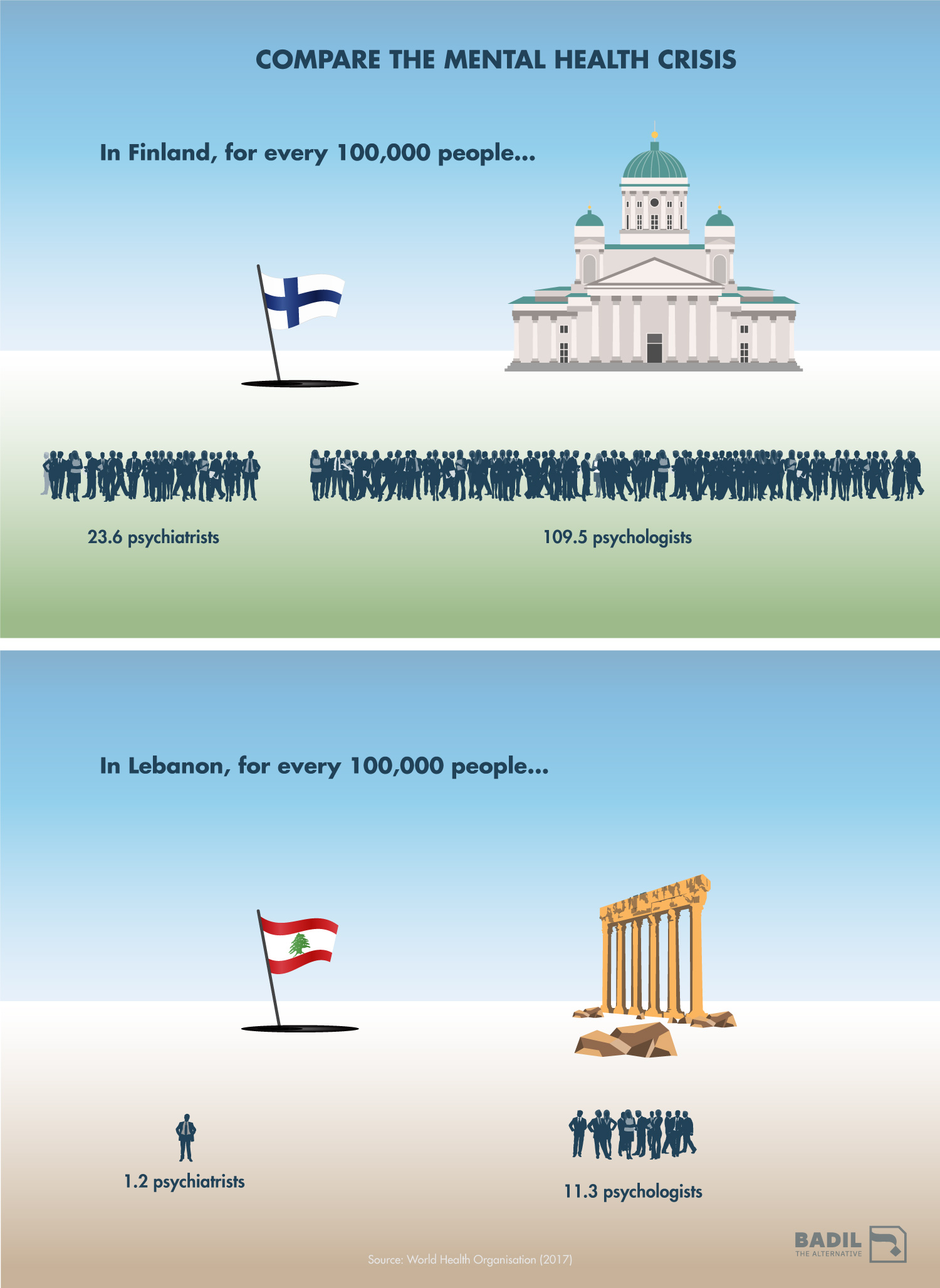

Before October 2019, the Ministry of Public Health (MOPH) assigned a pittance of its budgetary allowance to mental health services. Today, mental health allocations account for around 1% of MOPH’s overall budget – well below half of the global median spend, which is 2.4% of government health finances.

The government’s low prioritisation of mental health care stands at odds with Lebanon’s tortured history. The population still struggles with intergenerational trauma arising from the civil war (1975-1990), the emotional scars of which persist for both survivors and their descendants. Since then, post-war generations have suffered their own series of traumatic episodes, including the 2006 war, the country’s ongoing economic crisis, and the Beirut Port explosion.

Even in these current times of deprivation, the state has some options to arrest the country’s slide into a mental health disaster. First, MOPH should commission a nationwide assessment of mental health, given that the latest comprehensive study dates back more than ten years.

This essential step would help the government to identify needs and craft responsive policies accordingly. One such initiative would almost certainly be a mental health awareness drive, which could counteract social taboos against seeking help for mental health challenges.

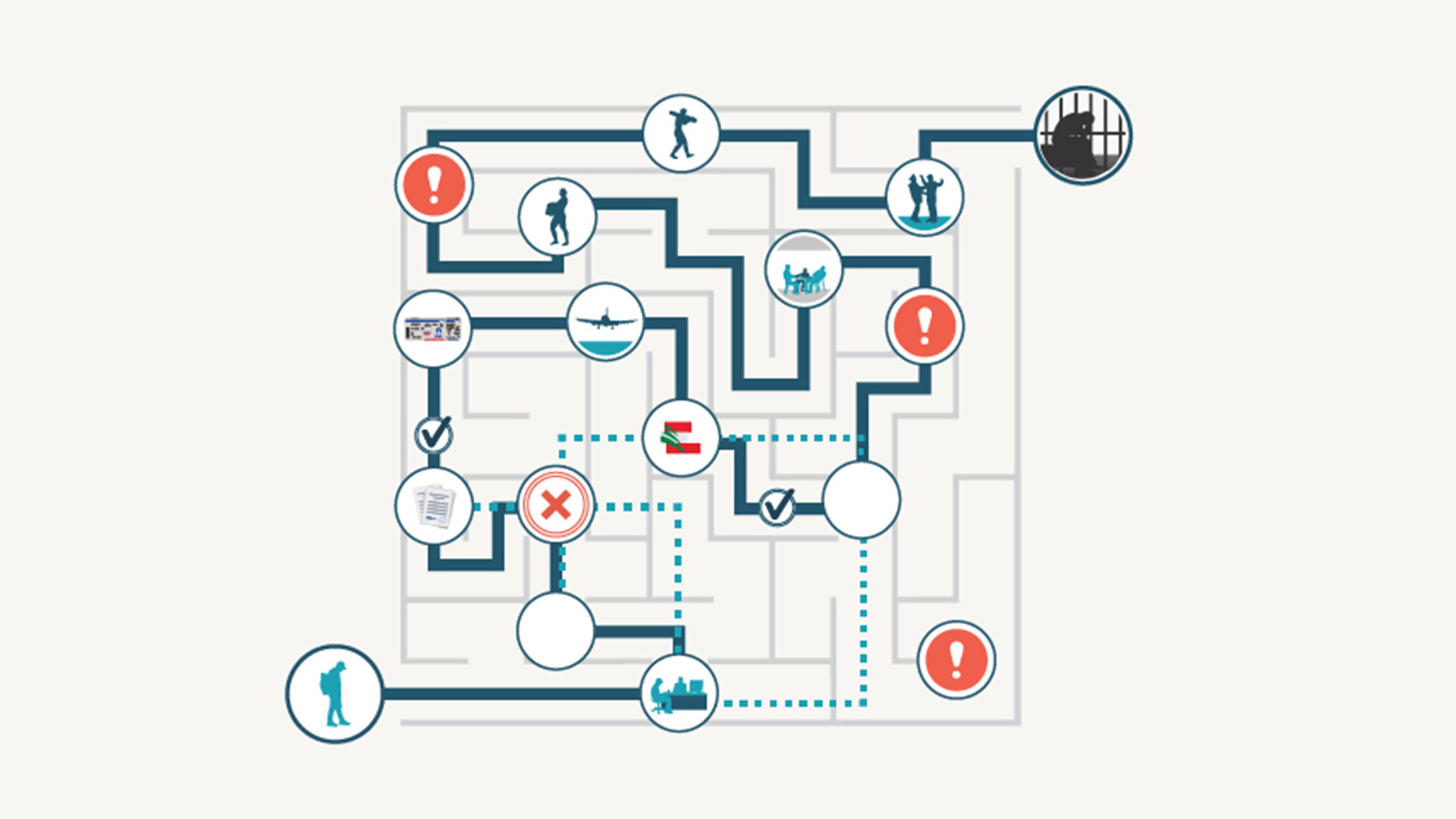

The government must also consider immediate ways to broaden public access to mental health services. MOPH could partner with international partners to provide funding to mental health professionals – including psychiatrists, psychologists, and psycho-social support workers – to offer financial incentives to remain in Lebanon. In parallel, programs should explore the potential of online counselling services, allowing the Lebanese diaspora and other service providers abroad to help.

What will not suffice is for the nation’s political elites – the source for so many enormous obstacles plaguing Lebanon – to continue storing their faith in Lebanese “resilience.” This stoicism in the face of adversity – which the psychologist Aziz diagnoses as “learned helplessness” – does not offer a long-term solution to Lebanon’s mental health collapse.

“Overall, resilience is a double-edged sword,” Aziz explained. “It helps you survive and adapt, but […] it sometimes makes you accept things [for example, from the government] that you would not accept in different circumstances.”

[i] Lebanese Psychiatric Society, 2022, “The Impact of the crisis on the career plans of psychiatrists in Lebanon”.