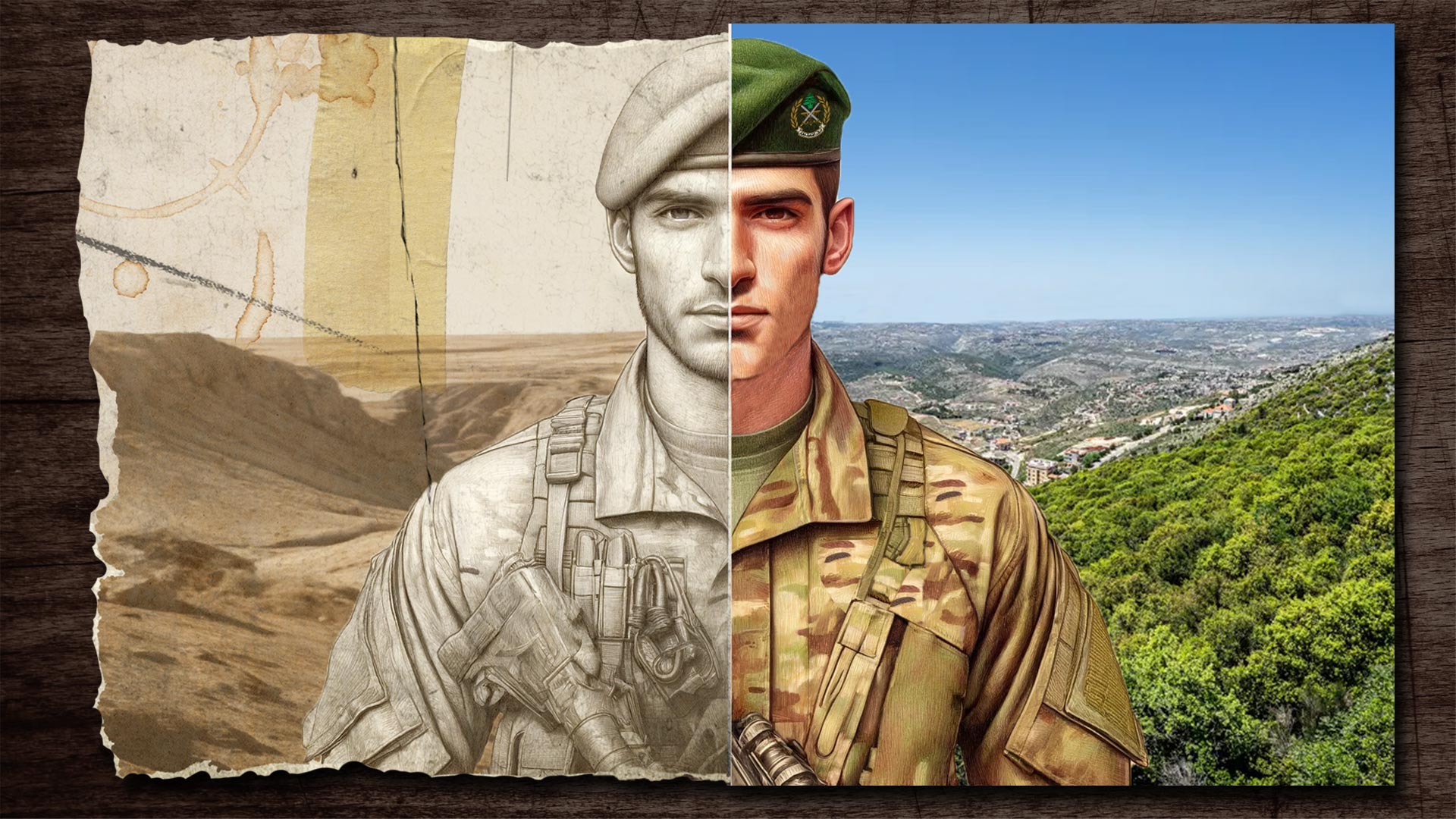

A centrepiece of continuing western efforts to stave off a full-blown war between Israel and Lebanon has been to push for the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) to replace Hezbollah along the country’s southern border.

After Hezbollah’s patron, Iran, carried out direct drone and missile attacks against Israel this month, the onus to pacify Lebanon’s southern border and prevent a regional conflict has only become more acute.

However, the western peace approach, led by Washington, is very much tongue-in-cheek. Washington and the West know all too well that without a regional political solution the last thing Hezbollah will do is cede even an inch of its southern stronghold. What is less appreciated, though, is that bankrolling the LAF without truly reforming it risks forever perpetuating Lebanon’s military dualism, whereby Hezbollah’s military wing operates autonomously from the national army.

Institutional bloat, accusations of graft and political infighting have rendered the LAF highly dysfunctional, with little capacity to secure the country at large, let alone one of the world’s most volatile borders.

Western countries should be pushing for reforms necessary to make the LAF a viable national security institution instead of pushing the army to take up tasks it has little capacity to fulfil. And they have the leverage.

As the LAF’s largest international donor, the US has provided more than $3 billion in financial assistance since 2006, as well as most of the army’s aircraft, vehicles and military equipment.