Bread and Butter

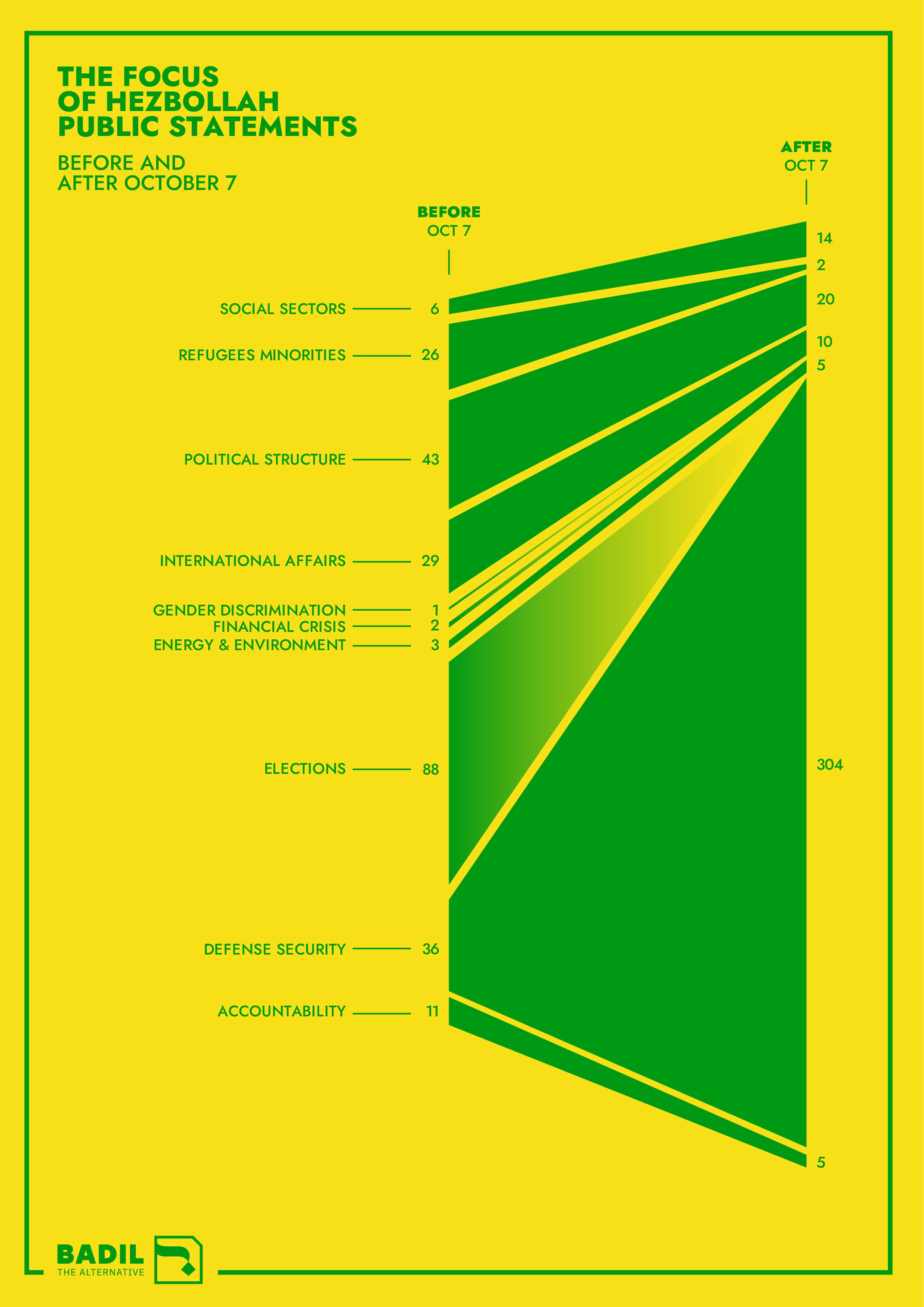

After more than a month of reciprocal hostilities at Lebanon’s southern border, which led to considerable economic harm to the region’s agriculture and infrastructure, the resistance narrative expanded to include bread-and-butter issues such as education, reconstruction, and compensations for those affected by Israeli shelling in areas along the Blue Line.

This amended discourse has in part been outsourced to Hezbollah’s political ally, Amal, the small member to the country’s so-called ‘Shia duo’. Caretaker Minister of Agriculture Abbas Hajj Hassan, a member of Amal, said on November 1: “I demand compensation for farmers affected by the Israeli bombing”. Similarly, in an interview to the newspaper Asharq Al-Awsat, the caretaker minister emphasised that “the biggest loss in this war was the olive season, with the burning of more than 53 old trees, and then forests, forest areas, and livestock”.

Joseph Daher, author of Hezbollah: The Political Economy of Lebanon’s Party of God, told The Badil that, “Hezbollah knows it is very much isolated politically and socially in Lebanon compared to 2006, where it had much wider popular support in terms of resistance”. He asserts that a series of events since then – including the May 7, 2008 clashes, Hezbollah’s intervention in Syria and its opposition to the October 17 Protests – have helped erode this broader support.

“We have seen several incidents between Hezbollah and other segments of society, the Tayouneh Incident being a prominent one,” that demonstrate these inter-Lebanese fissures, according to Daher. He adds that while “ideology plays an important role for Hezbollah’s discourse, it has been subordinated to other political questions and interests”.

As tensions along the Blue Line exacerbate Lebanon’s misery, the party’s discourse on the war is now expanding to encompass its supporters’ struggles to get by. MP Hassan Fadlallah said on November 27: “We in Hezbollah started paying compensation, and we carried out statistics at the southern level, and surveyed these damages (…). What we are offering to those affected is the money, capabilities, and efforts of Hezbollah.”

Looking Ahead

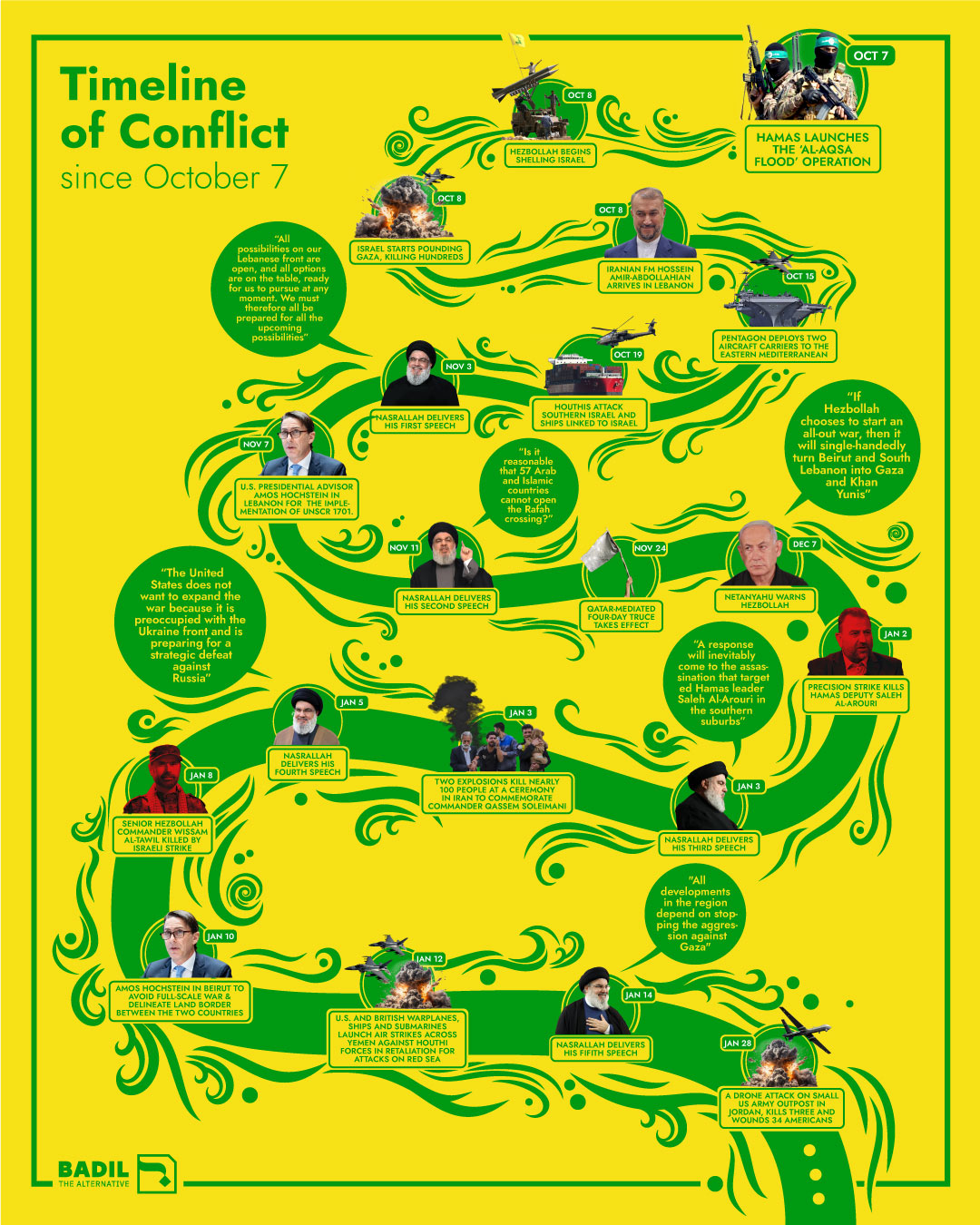

Nasrallah’s speech on January 3 gained new significance in the wake of Al-Arouri’s assassination. In his message, Nasrallah reiterated that his party would negotiate with Israel to curb tensions along Lebanon’s southern border only if the war in Gaza ends. As has been shown, however, this message must be interpreted within the wider context of Hezbollah’s public pronouncements since October 7.

The party’s evolving rhetoric is testimony to its constant balancing between ideology and expediency, especially as Lebanon struggles with a four-year economic crisis and a stalled recovery from the 2020 Beirut Port Explosion. In this challenging context, four out of five Lebanese people live in poverty, among which 36 percent are below the extreme poverty line. A survey by al-Akhbar, a pro-Hezbollah Lebanese newspaper, revealed that 68 percent of respondents voted “No” to the following question: “Do you support opening the southern front and immediately going to war”. Despite their belligerent rhetoric, Hezbollah’s leadership knows that many Lebanese are not ready for a full-scale war.

This shifting narrative on the war suggests that Hezbollah is far from being a monolithic entity. Instead, as Nicholas Blanford, a senior fellow and Hezbollah expert at the Atlantic Council, describes it, Hezbollah is a ‘coalition of shifting views’. The rapid changes and nuances in Hezbollah’s discourse indicate that the movement retains its rational pragmatism, switching narrative track as it deems necessary, based on its own strategic and political considerations. For now, Hezbollah appears to see the risks of war as too high, seeks to preserve the status quo.