EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The tragic irony that the offices of Lebanon’s state electricity utility – Électricité du Liban (EDL) – were one of the primary infrastructure casualties of the Beirut blast of 4 August 2020 did not escape most Lebanese. Authorities’ persistent failure to meet the energy needs of the population have for decades been a central symbol of the same state corruption and mismanagement that caused the blast.

The national grid suffers from both technical and regulatory deficiencies and relies overwhelmingly on expensive and highly polluting imported fuel-oil. Since the civil war, EDL has burned through public funds to secure barely enough fuel to keep the network operational – a financial burden that has become untenable during Lebanon’s ongoing financial crisis. Even during a global pandemic, Lebanon made global headlines with the nation’s parlous electricity network forcing closures of essential services including water pumps and hospital life-support systems.

Regulatory hurdles and political manipulation have prevented much-needed technical reforms, which would make electricity production more reliable and less expensive. Lebanon’s sectarian leaders have repeatedly frustrated the establishment of an independent electricity regulatory authority (ERA) capable of bringing Lebanese power production sector into the 21st century.1

Instead, the government has tolerated only the stop- gap solution of private diesel generators to supplement EDL’s poor coverage—which supplies only around 1600 MW from an average total demand of 3000 MW. Lebanese households then pay additional,

inflated power bills for the heavily polluting and inequitable diesel generators. The country’s elites have permitted this informal concession to politically connected generator owners, while largely precluding municipalities and community groups from producing their own electricity more sustainably.

Many technical reports have set out Lebanon’s best pathway out of this quagmire: renewable energy. Lebanon enjoys considerable potential to develop renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, and hydro power – now competitively placed to provide electricity for communities, households and industry – and the legislative and financial reforms required to open the way for rapid renewable energy expansion are well known.

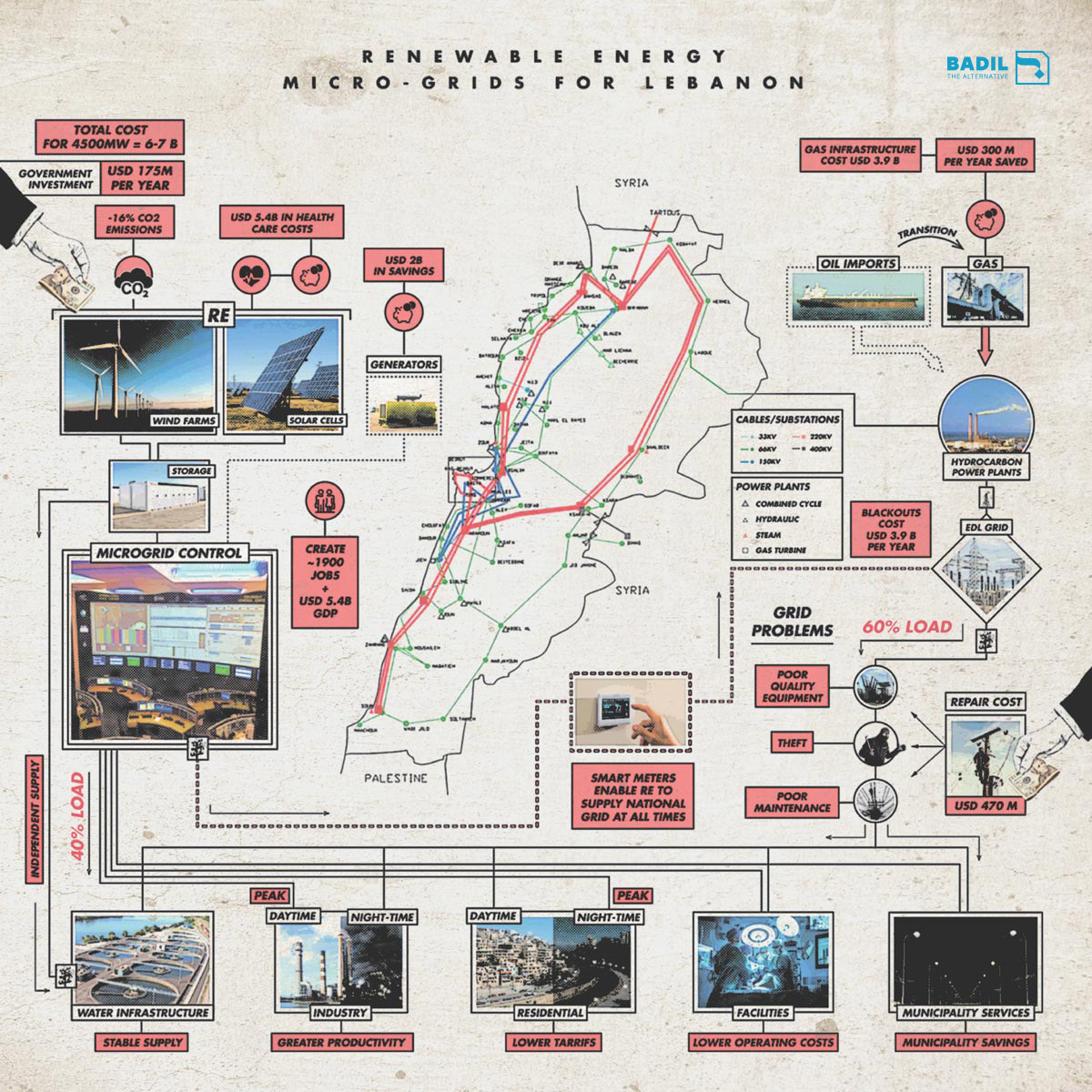

Yet, in 2018, renewable energy output accounted for less than 3% of total electricity generation.2 Over 4,700 MW of additional renewable energy capacity is needed in the next 10 years to meet the Govern- ment’s target of 30% of renewable energy generation by 2030.3,4 Least-cost modelling has identified a tar- get of 40% of renewable energy as a feasible goal to be achieved within a decade. This would replace nearly all diesel generators with renewable energy.5

While Lebanon requires nothing short of a compre- hensive overhaul of EDL’s national grid, there are op- tions for immediate action.6 With government support, communities can begin supplementing their energy needs with renewable energy through ‘micro-grids’ that already exist outside EDL’s system.7 This approach would allow communities to receive myriad benefits, such as better air quality, more reliable coverage, cost savings, and enhanced community ownership of key infrastructure and intra-communal trust.

SYSTEM OF A DOWN:

LEBANON’S BROKEN ELECTRICITY SECTOR

Lebanon’s ongoing fuel crisis has drawn renewed international attention to the country’s thoroughly dysfunctional electricity system. The country’s two main sources of power – state electricity provider Électricité du Liban (EDL) and privately owned generators – both rely entirely on imported liquid fuels (diesel and oil).8 With fuel becoming unaffordable, persistent blackouts have ensued across the country, with neither the national grid nor private generators able to operate consistently. At its lowest ebb, the fuel crisis forced the closure of hospitals and other essential services, accentuating the rapid decline in average living standards. The shoddy public-private electricity sector bears other costs for the Lebanese people, including increased living costs, widespread environmental damage, and impaired physical health. Blackouts resulting from patchy electricity service pose an additional strain on the Lebanese economy – in 2016 alone, electricity outages were estimated to have cost individuals and businesses US$3.9 billion.9

EDL: PUBLIC ENEMY #1

For decades, EDL has been the lead culprit in Leb- anon’s electricity woes. The state-owned operator is the sole operator of the national electricity grid, which provides inadequate coverage and imposes an enor- mous financial burden on Lebanon. Since 1993, the government has been forced to subsidise EDL’s budget shortfalls at a cost up to US$2 billion per year – mak- ing the energy sector responsible for 43% of Lebanon’ public debt.10 EDL has primarily incurred these losses by importing fuel-oil purchased in US dollars. Accord- ingly, EDL’s financial difficulties have drastically wors- ened amidst Lebanon’s ongoing currency devaluation. Even before the current economic crisis, fuel prices and the cost of electricity generation had increased significantly since the 1990s, when EDL tarrifs were set at US$0.095 per kilowatt hour (KWh). These tariff rates still apply, even though the true cost of providing electricity in Lebanon has risen to between US$0.16 to $0.23 US cents per KWh.11 On top of this loss-mak- ing business model, internal mismanagement has driven up EDL’s debts. In 2019, tariff collection rates stood at just 57% of amounts owed. In the same year, theft and inefficient infrastructure caused EDL to lose around 35% of total energy generated.12

PRIVATE GENERATOR OPERATORS: PUBLIC ENEMY #2

Many Lebanese households, frustrated by EDL’s poor coverage levels, have long resorted to backup diesel generators as a supplementary power source. Private generator operators have constructed their own micro-grids for electricity across the country, capable of supplying electricity at times when the national supply cuts out. Use of backup generators has grown rapidly since the mid-2000s, from 22% to more than 50% of demand being covered by generators in 2020.13 This stop-gap solution has cost the Lebanese public dearly, which pays nearly $2 billion annually to private generator operators to cover EDL’s shortcomings.14 These additional expenses have also amplified wealth disparities, with only the relatively wealthy able to afford to pay multiple electricity bills.

The current fuel and energy crisis has demonstrated that generators fail to address any of Lebanon’s fundamental energy problems. Using generators to produce electricity exacts enormous financial and environmental tolls, while falling into the same chronic dependence on imported fuel-oil that plagues EDL’s national public network.15 In this way, private generators worsen Lebanon’s energy insecurity, rather than harnessing the potential of alternatives to fossil fuels. In the meantime, generators have contributed to Lebanon – with its relatively small population – suffering from air pollution and cancer rates on par with large, heavily industrialised cities.16 Lebanon has very high cancer rates, particularly in areas close to industrial and power production sites.17 Air pollution in Lebanon is estimated to have caused the deaths of more than 1,800 people in 2013 and a loss to society of around $2.6 billion.18

The rapid proliferation of private generators since the 1990s – now estimated at over 32,00019 – saw the government attempt flimsy price regulations in 2011, when the Council of Ministers (COM) issued a decree to permit the Ministry of Energy and Water (MoEW) and Ministry of Economy and Trade (MoET) to regu- late the sector. De-facto regulation of generator oper- ators through price-setting (no matter how poorly im- plemented) provided tacit legal consent for generators to sell energy publicly when EDL is unable to provide electricity – a privilege renewable energy providers have been so far denied.

Generator owners have thrived off massive profits and opaque and poorly regulated monthly tariffs based on the number of cut-off hours or “per kilowatt hour” con- sumption20 with rates as high as US$0.45 per kilowatt hour.21 Their business model – reliant on a stable ex- change rate and profitable fuel importation – is how- ever being challenged in the current financial crisis. The unaffordability of US dollar-reliant fuel, deprecia- tion of the Lira, and the impoverishment of most of the population has meant few can afford to pay generator fees in 2021 – and made renewables a far more com- petitive offering.

INTERNAL INERTIA

While Lebanon’s energy production sector urgently needs effective decision-making, domestic politics remain mired in self-interest and idleness. Past reform proposals have stumbled at myriad political obstacles. These include sectarian squabbling over the location of new power plants; misappropriated procurement and contracting processes;22 opaque decision-making in flagrant contradiction of international expert advice; and unrealistic, rushed plans.