THE SECOND HURDLE: ENERGY EFFICIENCY

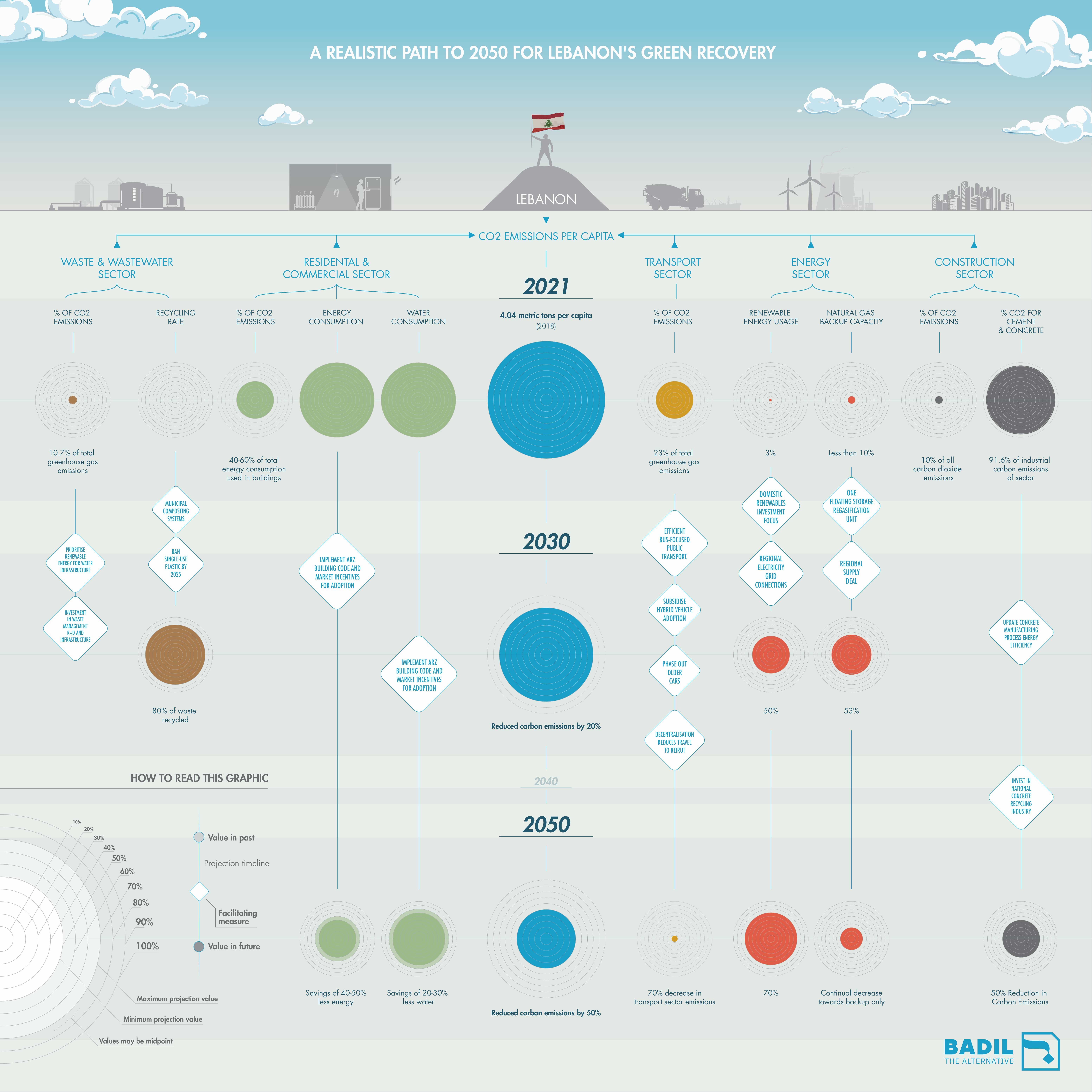

Changes to supply-side dynamics alone are not enough to bring about the scope of change needed for Lebanon. In 2018, Lebanon emitted 4.04 metric tons of carbon dioxide per capita, while neighbouring Jordan, which uses much less fuel oil and more renewable energy and gas emitted 2.47 metric tons per capita.13 What’s more, Lebanon’s energy consumption is set to grow by an estimated 7% per year to 2030.14 Such growth must be met by energy efficiency measures across infrastructure, appliances, and individual behaviours.

Lebanon’s reliance on costly electricity production would nosedive if energy efficiency promotion were taken seriously. The 2016 National Energy Efficiency Action Plan (NEEAP) – the 2021 update of which was yet to be published at the time of writing – identifies

14 primary initiatives that, if implemented, would reduce electricity power demand by 4.83% of 2020 usage levels. However, the initiative to promote energy efficient equipment had only achieved 8% implementation by 2016.15 Based on the government’s own NEEAP, total national electricity consumption from appliances would drop from 4,250 gigawatt hours (GWh) per year to 3,244 GWh per year by 2025 – a 24% improvement.16 In the industrial sector, energy efficiency measures have already achieved an average 39% reduction in energy costs.17 Yet to date, Lebanese consumers remain largely unaware of energy efficiency ratings for appliances. To make matters worse, limited finances sometimes make it difficult to upgrade to more expensive technology.18

TRANSPORT: DRIVE TOWARDS THE GREEN LIGHT

The transport sector currently imposes untold difficulties on Lebanon’s economic development. Lebanese commuters rely heavily on private cars instead of public transport. The widespread use of privately owned vehicles contributes to the transport sector draining more than 40% of Lebanon’s oil consumption – an unaffordable burden on almost all consumers’ pockets. Omnipresent private cars further damage economic

productivity by driving up traffic congestion. Each year, Lebanese commuters spend an average of 720 out of 4,380 productive hours on the road, costing an estimated US$3 billion per year in GDP.19 The problem is compounded by a lack of decentralised service and job provision outside of Beirut. Over 500,000 cars enter Beirut each day to access, jobs, schools and services that are not available elsewhere.20

The only viable alternative for Lebanese commuting is revitalised public transport networks, which would also reduce the country’s carbon footprint. At present, the transport sector is responsible for 23% of overall greenhouse gas emissions, while also being the country’s main source of urban air pollution.21 Within Beirut, public transport accounts for no more than 20% of all trips. Most of these journeys occur in a shared taxi, or service, with just 2% of trips taking place in buses and vans.22 Now that Lebanese commuters struggle to meet rising fuel costs, it will make economic and social sense to boost Lebanon’s public transport capacity, starting with the restructuring and modernization of the bus system. Electric vehicles will become more widespread, contingent on meeting upfront capital requirements and improving Lebanon’s energy security. Implementing these direct measures alone, without decentralisation, would do more than slash fuel bills. They would also bring down transport sector carbon emissions by 67% by 2040, compared to a business-as-usual scenario.

BOX I: Sharing Economy Box

In economic models centred on sustainability and circularity, waste and pollution are considered design flaws rather than inevitable by-products.23 One of the main differences from current consumption practices is in designing products to be reused, repaired or remanufactured, and keeping them in circulation so they do not end up in landfills.

Cases of acute and long-term crisis have often been major drivers for moves towards resource efficiency. Cuba for example is ranked as the world’s most sustainably developed country – a situation that has occurred both through policy and necessity.24 Similarly Lebanon in 2021 is being driven by necessity of its import limitations to rapidly move toward more sustainable practices. Across all sectors these practices are often characterised by new modes of capital ownership based on sharing – through co-sharing, leasing, and collaboration – rather than outright ownership.

There is also a business case to be made in support of the sharing economy. Businesses incur lower capital ownership costs and get more use value from their capital over its lifespan, while individuals who cannot afford things outright or do not use them often, can still gain access to goods and services at cheaper rates based on subscription and rental agreements. Increasingly driven by corporate social responsibility, as well as long-term environmental risk assessments, investors are also more inclined to fund enterprises that are following circular economic principles.

CONSTRUCTION AND INDUSTRY: BUILD BACK GREENER

The construction and industrial sectors are large contributors to Lebanon’s ruinous import dependence. Both sectors have been reliant on imported inputs and high-polluting practices. Construction industry stakeholders estimate that of non-concrete materials, 90% are imported and the construction sector accounts for nearly 10% of the country’s carbon dioxide emissions – of which cement manufacturing is responsible for 91.6% – while comprising only 3.8% of GDP.25

Lebanon’s resource and capital scarce economic context is already pushing industry toward sustainability measures. Lebanese industry is the largest investor in renewable energy, given renewables’ superiority for business productivity and reliability compared to EDL’s electricity supply. Currently, 20% of all rooftop photo- voltaic systems are installed within the commercial sector.26 Local products such as high quality local agricultural compost and recycled tyres are seeing demand growth as their products now out-compete imported alternatives.27

The 2015 Sustainable Consumption And Production Action Plan For The Industrial Sector highlighted that improving Lebanon’s trade balance through producing and exporting highly sophisticated products was a priority for moving the economy towards a more sustainable footing.28 The report noted Lebanon as a regional exception in its production of highly sophisticated products and indicated the industrial sector should promote whole-of-life cycle approaches and eco- design to capitalise on Lebanon’s free trade agreement with the EU, as well as other trading relationships.29

WASTE MANAGEMENT:

WASTE NOT WANT NOT

Lebanon’s waste crisis represents the symbolic inverse of its vast import expenditure. The money used to buy those goods has run out and so has the land space for dumping them afterward. Instead of bundling up the waste and dumping it into the sea

as “land reclamation,” Lebanon needs whole of life- cycle solutions to consumption and waste, that also derive major change from behavioural practices and efficiency measures.30

Emissions from waste and wastewater, contribute to 10.7% of Lebanon’s total greenhouse gas emissions – largely derived from the decomposition and burning of waste in dumped at the 504 municipal waste dumpsites spread around the country, and the discharge of wastewater without prior treatment in the Mediterranean sea, riverbeds and septic tanks.31

Encouragingly (or dishearteningly), most of Lebanon’s waste can already be recycled. Around 80-90% percent of current refuse could be dealt with sustainably, without relying on landfills.32 Waste management solutions in Lebanon’s context require interventions at the generation, recovery, and processing stages – with parallel efforts to change cultural attitudes at all stages. Market interventions such as Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) systems are also needed to push manufacturers to use reusable or recyclable products and be held responsible for the lifecycle of their products.33 Recycling industries already show potential for job creation if they can be formalised and expanded. Prior to 2019, 10% of Lebanon’s exports came from exported scrap metal largely collected by informal workers.34

GREEN BUILDING CODES:

A GOOD HOME IS A GREEN ONE

Most Lebanese households pay unnecessarily high electricity bills due, in part, to weak building codes and energy-inefficient housing. In other countries, homeowners make huge savings from constructing

energy efficient houses. In India, certified green buildings used 40 – 50% less energy and 20 – 30% less water compared to conventional buildings. In more resource-hungry developed nations such as Australia, the gains were even higher.35 These savings lead to lower bills for residents and business occupants, lower construction costs and even higher property values.

At present, Lebanese regulations do little to incentivise builders or citizens to construct energy-efficient houses. The current building code includes only the most basic sustainability and energy measures such as mandated double-layer walls, and minimum levels of glass on the exterior of the building. The Lebanese Green Building Council (LGBC) has developed a green buildings ratings system (ARZ) based on international best practice. Uptake of ARZ has so far been weak. Nevertheless, the LGBC is working with the Order of Engineers and Architects in Beirut and Tripoli to incorporate the ratings system into existing permit processes.36

Now, Lebanon’s economic crisis is taking over in incentivising homeowners to adopt more sustainable building techniques. Many new construction materials have become prohibitively expensive, leading builders to show increased interest in recycled inputs – regardless of government (in)action. Building codes can support this trend by ensuring sustainable procurement and construction, while also regulating material quality and standards. These steps would ensure that sustainability measures are maximised throughout the value-chain.37

As suggested by the name, green building can make a massive contribution to Lebanon’s environmental recovery. As the primary source of energy and material consumption, buildings and the regulations on their design and construction are key entry points of control for up-and down-stream sustainability gains.38 The building sector has some of the highest potential for reducing greenhouse gas emissions – estimated at a potential 50% cut in current carbon emissions by 2050 – through direct measures in building design and energy sourcing.39