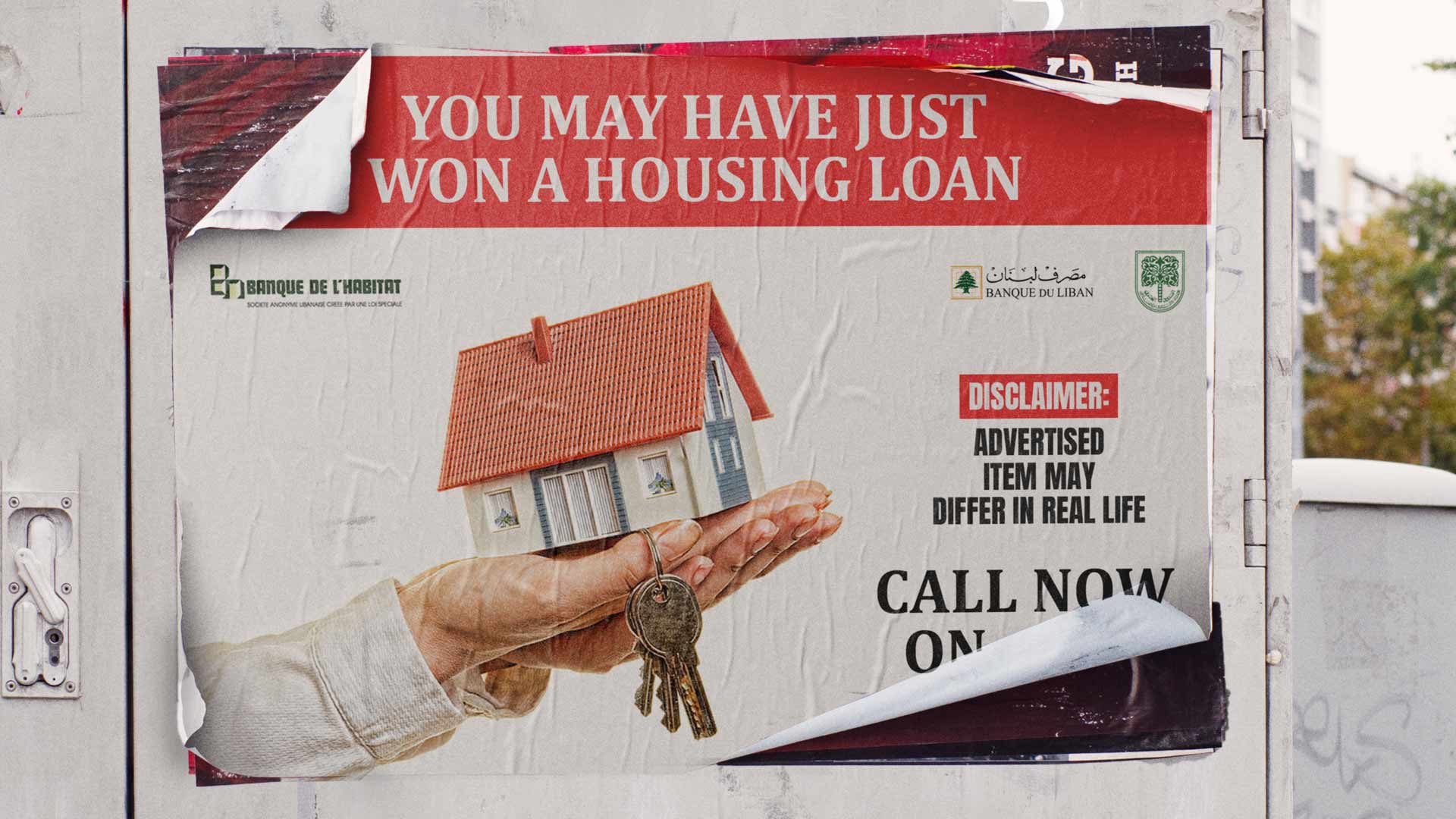

The deadline to submit an application for Lebanon’s only tangible housing policy with Lebanon’s Banque De L’Habitat (BDH) ended on September 30. The relaunch of the loan programme, after a three-year hiatus, marks the restart of a subsidised loan programme that was the cornerstone of a bloated housing sector and a hallmark of Lebanon’s failed banking system. This time the programme is being framed as one which targets low-income earners, but it has stalled as soon as it started.

Having opened online applications in June, the BDH offers long-term loans to purchase or renovate a house, and to install solar panels. The loans are designated in Lebanese pounds (LBP), at a fixed interest rate of 4.99%.

“We received over 180,000 website visits and 10,000 applications,” BDH Chairman Antoine Habib told Badil. “Unfortunately, people have difficulties obtaining official documents due to the public sector strike and we cannot lend out money without [the required] official documents.”

However, that hardly seems the only obstacle in play. With an estimated 80% of the Lebanese population plunged into poverty, virtually every citizen could use a helping hand in buying or renovating a home. [1] Indeed, on paper, the BDH programme looks promising. On screen too, as one can simply apply online. Yet, in reality, things are not as rosy as they seem.

Firstly, eligible for a loan are Lebanese households with a net monthly income between LBP six million to LBP 20 million and Lebanese expats with a salary between US $1,000 to $2,000 a month. [2] Applicants should, moreover, have had a regular job for at least three years. With the current (official) unemployment rate nearly 30%, access to the loan programme is by no means a given for most Lebanese.[3] But that is not all. The average salary currently stands at LBP 2.3 million, about a third of the minimum income required to qualify for a BDH loan.[4][5]

Secondly, levels of financial exclusion have been exacerbated by the Lebanese economic crisis. In 2017 only 44.8% of Lebanese adults above the age of 15 owned bank accounts, while that number plummeted to only 20.7% in 2021, which leaves the vast majority of the population unable to apply for a loan. [6] Regular bank statements are a requirement for obtaining the loans, yet opening a bank account in the current climate is virtually impossible, especially without access to foreign currencies.

Thirdly, the maximum loan amount to purchase, renovate, or install solar panels is LBP one billion, 400 million, and 200 million respectively. This invariably means that the highest possible loan is only worth around US$ 26,000 (at the parallel market rate), which brings into question the quality of housing individuals can purchase. Targeting low-income households, the BDH programme appears to be directed towards low-quality housing as well.

“The average price per square meter for an apartment in Beirut’s suburbs is around US$1,200,” said Roy Badaro, economic advisor to the Lebanese Forces. “This means that, even with a zero-interest rate, very few people can afford to buy an apartment. Unless they are expats.”

The three-year hiatus in subsidized housing has done little to reduce the already bloated real estate market. Property developers continue to set prices catered for international buyers and Lebanese expats. And, whilst average property prices have decreased by about 20%, according to Badaro, they remain out of reach for the majority of the population.

Funding Ambiguity

The BDH housing programme is funded by the Kuwait-based Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development (AFESD), which, as early as March 2019, agreed to provide Banque du Liban (BDL) with 50 million Kuwaiti Dinars (approximately US $161 million). Yet, today, more than three years later, the funds have still not been transferred.

“The loan programme has not been implemented earlier due to political, economic, and social reasons,” Habib told Badil.

According to Badaro, “AFESD is withholding the stimulus package because there is an outstanding US$ 120 million loan the Lebanese government has not paid back yet, and it will not release any funds until Lebanon does so.” AFESD did not respond to an interview request by Badil.

Habib explained that BDH received funding through a US$ 120 million loan from AFESD in 2016, however he did not provide details as to whether this loan was the reason behind the current delay in transfer.

Founded as a joint-stock company in 1977, BDH is a public-private entity with 80% of its shares owned by commercial banks and 20% by the Lebanese state. The BDH board includes representatives of Lebanese commercial banks such as Bank Byblos, Arab Bank, Bank Med, Banque Libano-Française and Bank of Beirut.

Housing or Banking?

“The [AFESD] loan is a move to recapitalize the BDL rather than provide quality housing for Lebanese families,” said Wassim Dbouk, Associate Professor of Finance at the American University of Beirut.

If AFESD transfers the promised funds a good chunk of the money is likely to be absorbed by the BDL through manipulating the Lebanese pound exchange rate. AFESD is set to transfer the funds in Kuwaiti Dinars, which the BDL will convert to LBP before transferring it to the BDH.

Conversion is likely to take place at the Sayrafa rate well below the parallel market rate. At the time of writing, one USD equaled LBP 29,800 on the Sayrafa platform and LBP 39,000 on the parallel market. The BDL did not comment before publication of the article.

“It doesn’t make sense at all,” said Dbouk. “It is a 30-year housing loan in an environment characterized by hyperinflation and a very high default risk due to the increasing cost of living and wage stagnation. It makes more sense to hand out loans in dollars.”

Critics of the BDH programme furthermore point at passed loan packages, which resulted in large profits for the banking sector and inflated real estate prices and pushed many Lebanese out of the real estate market.[7]

By injecting money – in the form of subsidized loans – into the housing sector, the stimulus package only delayed a much-needed market correction for Lebanon’s real estate sector. Priced in dollars, the sector mostly targets Lebanese expats.

“Before the economic crisis, at the end of 2018, the total amount of mortgages stood at US $13 billion, most of which was issued by commercial banks,” said Nassib Ghobril, chief economist at Byblos Bank. However, the number of Lebanese with a mortgage is estimated at only 6% of the population.[8]

The past social loan programs generally left low-income households and individuals behind. Most of the stimulus package was in fact pocketed by higher income brackets, as commercial banks were allowed to lend without an income cap. [9]

Lack of Policy

According to Housing Monitor, an “online platform for research, building advocacy and proposing alternatives to advance the right to housing in Lebanon”, the Lebanese state has, since the 1990s, ignored the urgent need for comprehensive measures addressing the country’s multifaceted housing crisis. Instead, the state adopted a singular approach of offering loans for home ownership without any further housing incentives.[10]

Certainly, soft loans can be a means to offer low- and middle-income households a pathway to home ownership. Subsidized loans should, nonetheless, be accompanied by other measures such as rent control, taxation of vacant apartments, and investment in infrastructure and public transport.

The BDH programme, despite launching its campaign, seemingly has a problem with financing. It is unclear how many loans, if any, BDH will be able to provide without AFESD funding. With no other loan options available, applicants will have to wait a little longer to buy or renovate their homes.

[1] Relief Web, 2021, “Multidimensional poverty in Lebanon,” Online at: https://reliefweb.int/report/lebanon/multidimensional-poverty-lebanon-2019-2021-painful-reality-and-uncertain-prospects

[2] Bank De L’Habititat, 2022, ”Who is eligible to benefit from a Purchase Loan?” Online at: https://www.banque-habitat.com.lb/en/loans/purchase

[3] ILO, 2022, “Lebanon and the ILO release up-to-date data on national labour market,” online at: https://www.ilo.org/beirut/media-centre/news/WCMS_844831/lang–en/index.htm

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] World Bank, 2022, “Global Findex Database,” Online at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/FX.OWN.TOTL.ZS?locations=LB

[7] Triangle, 2018, “A New Financial Deal for Lebanon,” Online at: https://www.thinktriangle.net/a-new-financial-deal-for-lebanon

[8] World Bank, Anton Badev et al., 2014, ”Housing Finance Across Countries,” Online at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/16821/WPS6756.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

[9] Housing Monitor, Abir Saksouk et al., 2020, ” Home Loans Exacerbate Inequality,” Online at: https://housingmonitor.org/en/content/home-loans-exacerbate-inequality

[10] Ibid.