EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

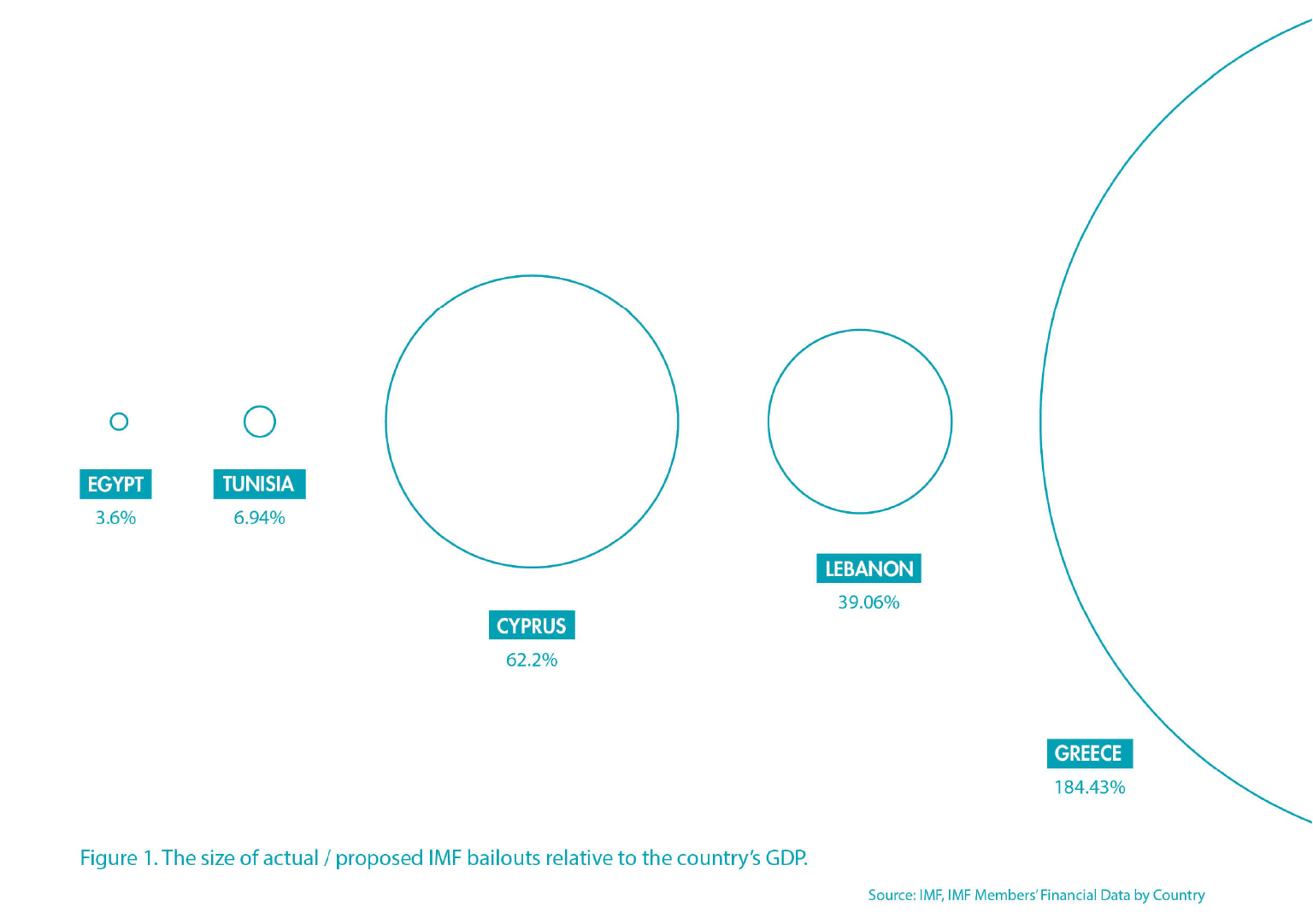

Defaulting on Lebanon’s foreign-held debt may have patched up the country’s financial wounds, but it has not stopped the internal bleeding. To achieve that, Lebanon will need a comprehensive reform package and a shot of fresh US dollars to recapitalise local banks and keep the economy moving. But, who will administer the shot? For a host of reasons, Lebanon is fast running out of willing international donors. Soon enough, Lebanon will be left with the world’s lender of last resort instead: the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

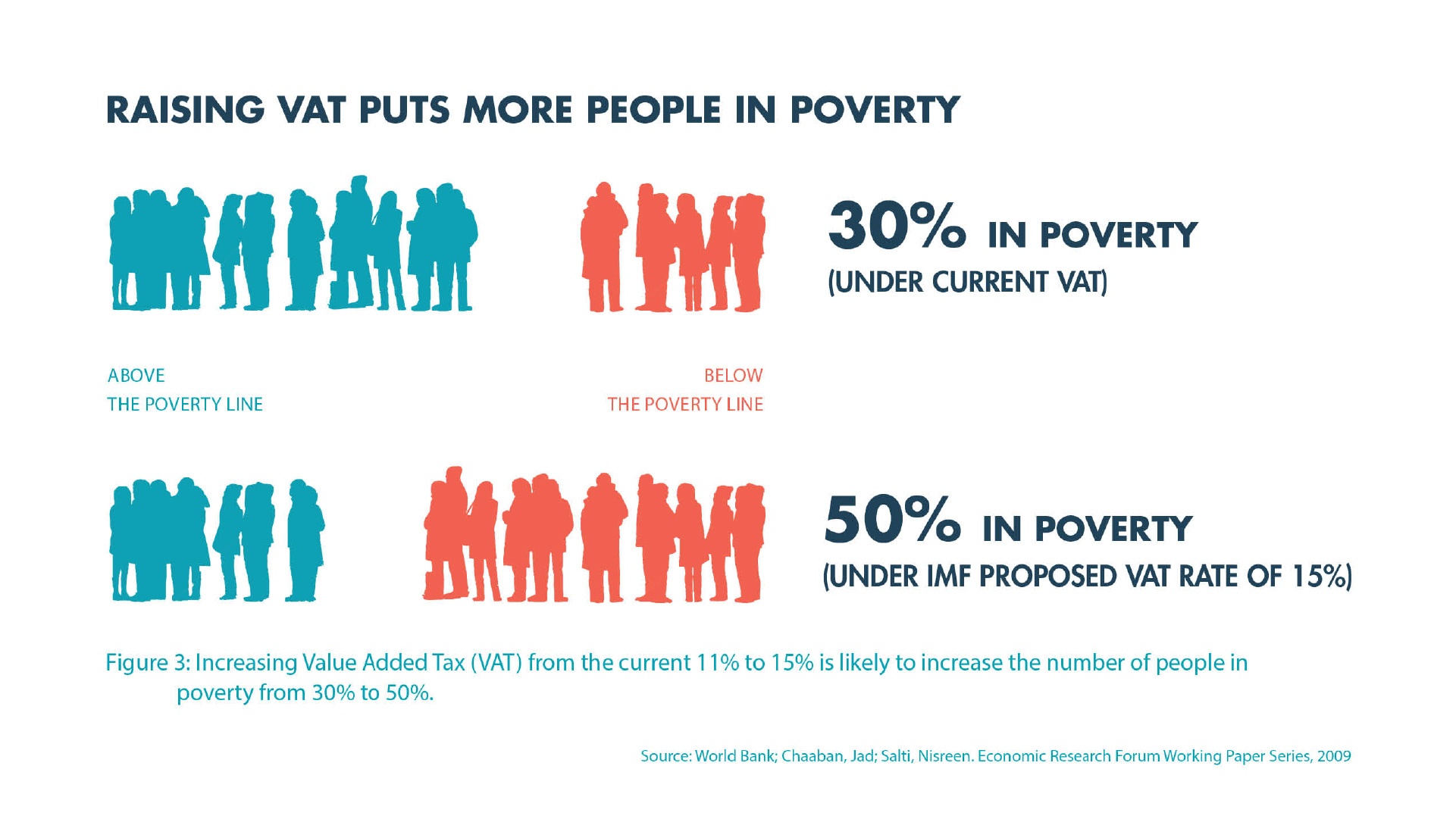

But there is a snag. The IMF is likely to demand economic measures similar to those which sparked a national uprising in October last year. A punitive package of reforms aimed purely at repayment of IMF loans and austerity would exacerbate inequality, push Lebanon deeper into recession, increase the debt-to-GDP ratio, and, in all probability, make repayment to the IMF almost impossible to achieve.

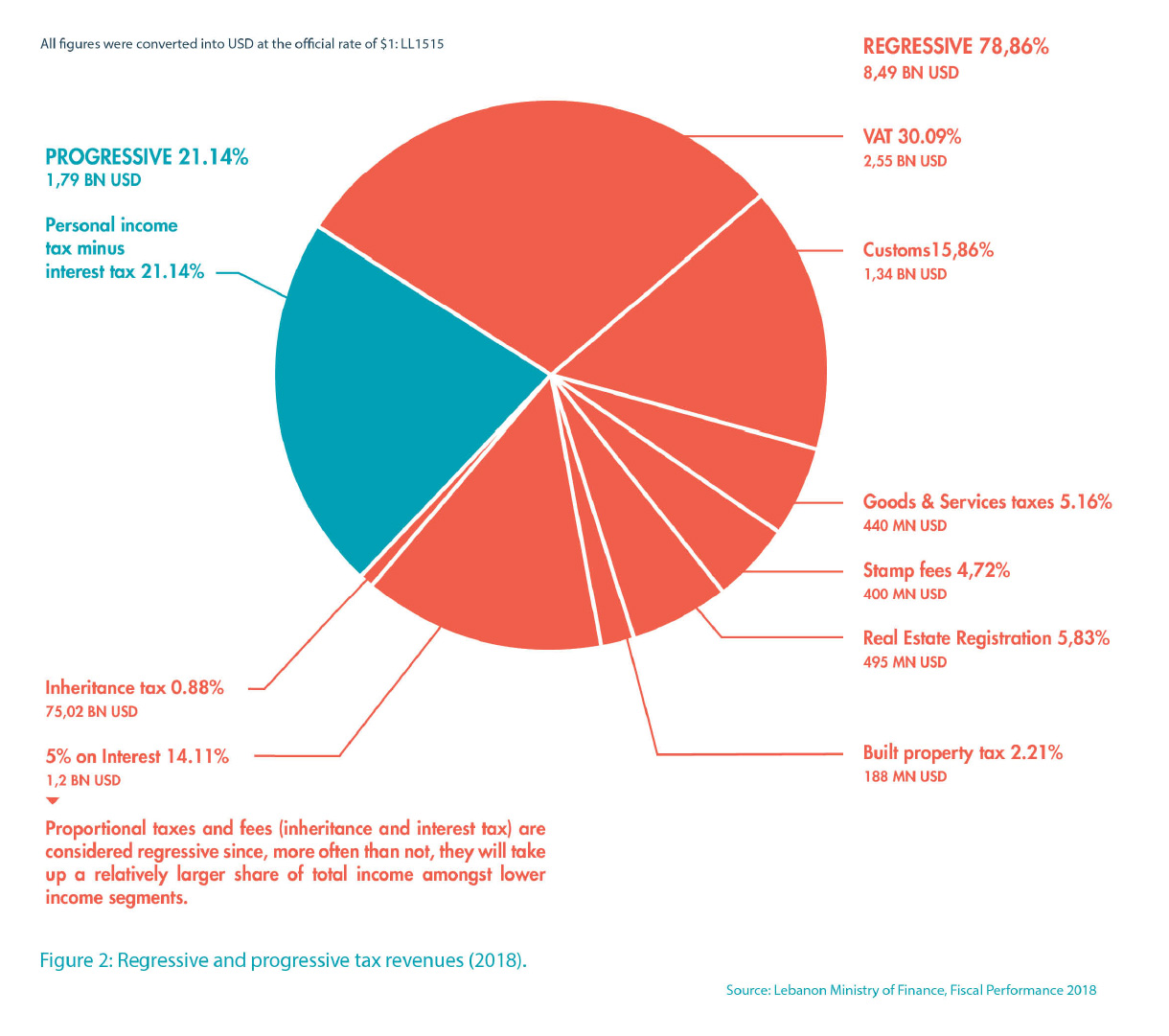

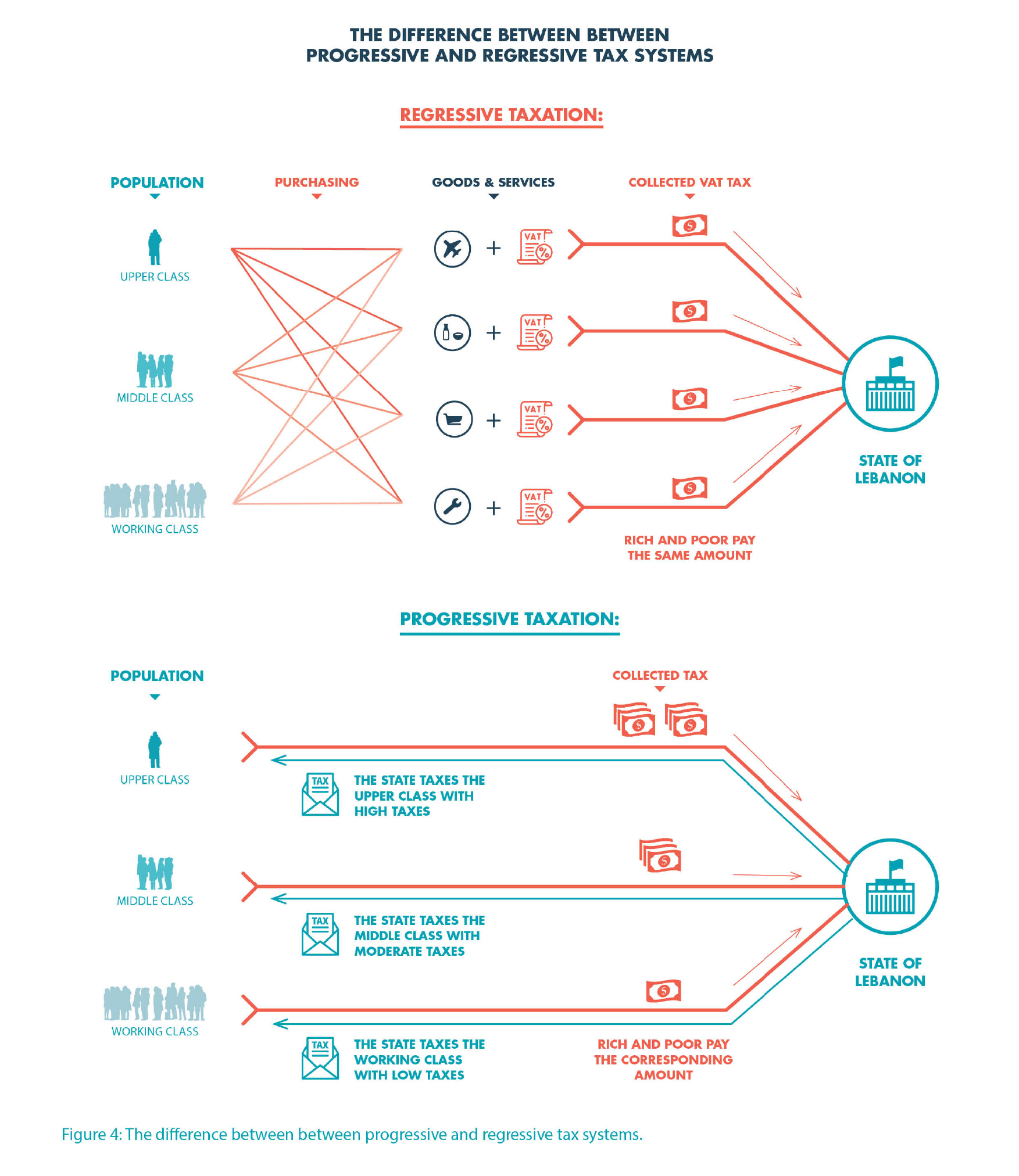

Instead, the IMF and policy makers should strike a deal which balances much-needed financial, economic, and institutional reform with the social realities of a country in the midst of an anti-establishment uprising. First and foremost, any IMF package will need to address how the burden of state financing is unfairly levied on the poorer segments of society.

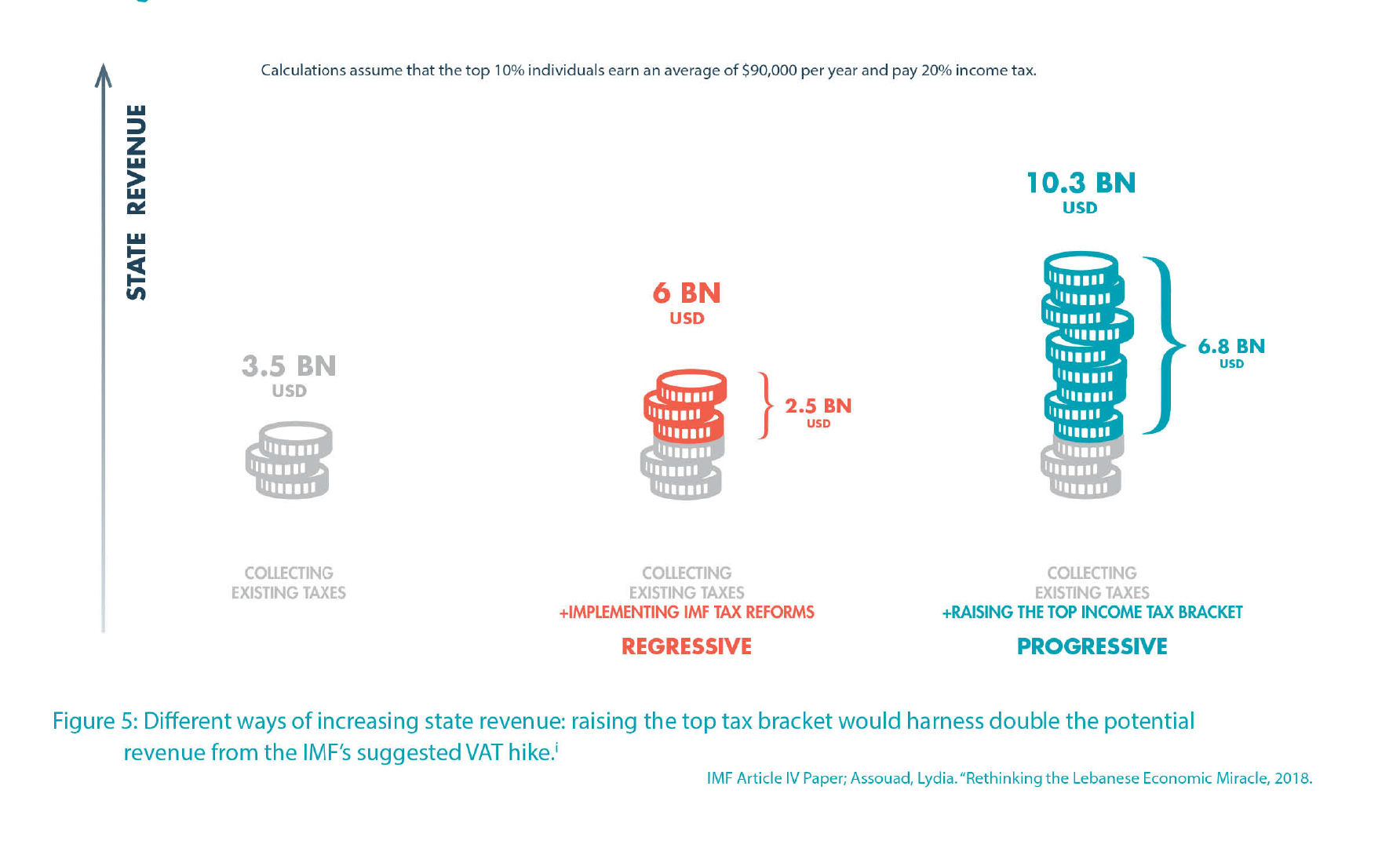

Progressive tax reform and collection will need to be at the heart of this process, with a focus on increasing collection rates and closing loopholes for income tax avoidance and evasion. The ludicrously low top tax rate of 25% should be the first to go—top taxpayers in OECD countries typically pay between 40% and 60%.i By simply increasing marginal taxes on high-income earners to 40%, the government could harness almost $7 billion per year. This is over double the potential revenue from the IMF’s suggested VAT hike which would hit the poor harder than the rich.

Privatisation, another typical IMF demand, should not be considered in the short term. Lebanon’s underperforming state assets have relatively low value, especially given the dire economic situation. In the current climate, privatisation would amount to a wasteful fire sale; instead, privatisation should only be considered in the medium-to-long term, when a future government can negotiate any sale from a position of strength. To get there, the government must implement long-awaited institutional reforms in the electricity sector, the telecommunications sector, and other key industries. Above all, Lebanon must establish and empower independent regulators, capable of defending the public good over private interests.

Otherwise, Lebanon will fall prey to the same fate as other countries that implemented hastily thought up IMF-led privatisation. Egypt and Tunisia, for example, did not have strong regulatory institutions to prevent regime elites from carving private monopolies out of former state assets. In Lebanon, that will mean that ministers kiss goodbye to their lucrative portfolios, which have long been cash-cows for their respective parties.

The IMF will be open to serious discussion with the Lebanese government. However, in return, Lebanese negotiators must be ready to bring meaningful policy suggestions to the table. Arriving empty handed would simply allow the IMF to impose its own agenda on a country which cannot afford austerity and regressive taxation. This time, the bill must be split equitably, with the richest shouldering their fair share of the burden.

INTRODUCTION

In March 2020, Lebanon made a historic decision. By opting to default and restructure Lebanon’s payments to foreign creditors, Prime Minister Hassan Diab’s government lost the country’s much-vaunted record of never having defaulted on a debt. In the preceding weeks, the looming March 9 deadline —when $1.2 billion in Eurobonds was due to foreign creditors— sparked much debate.

For those opposing the default, Lebanon may as well have upheld foreign-held debt payments, given they are a fraction of the total (around $12 billion at face value by the end of 2019, compared to $90 billion in total sovereign debt). Avoiding default might have bolstered Lebanon’s financial credibility, but the pro-default camp had a simple question: what is the value of saving face when market confidence is already at rock bottom?