Executive summary

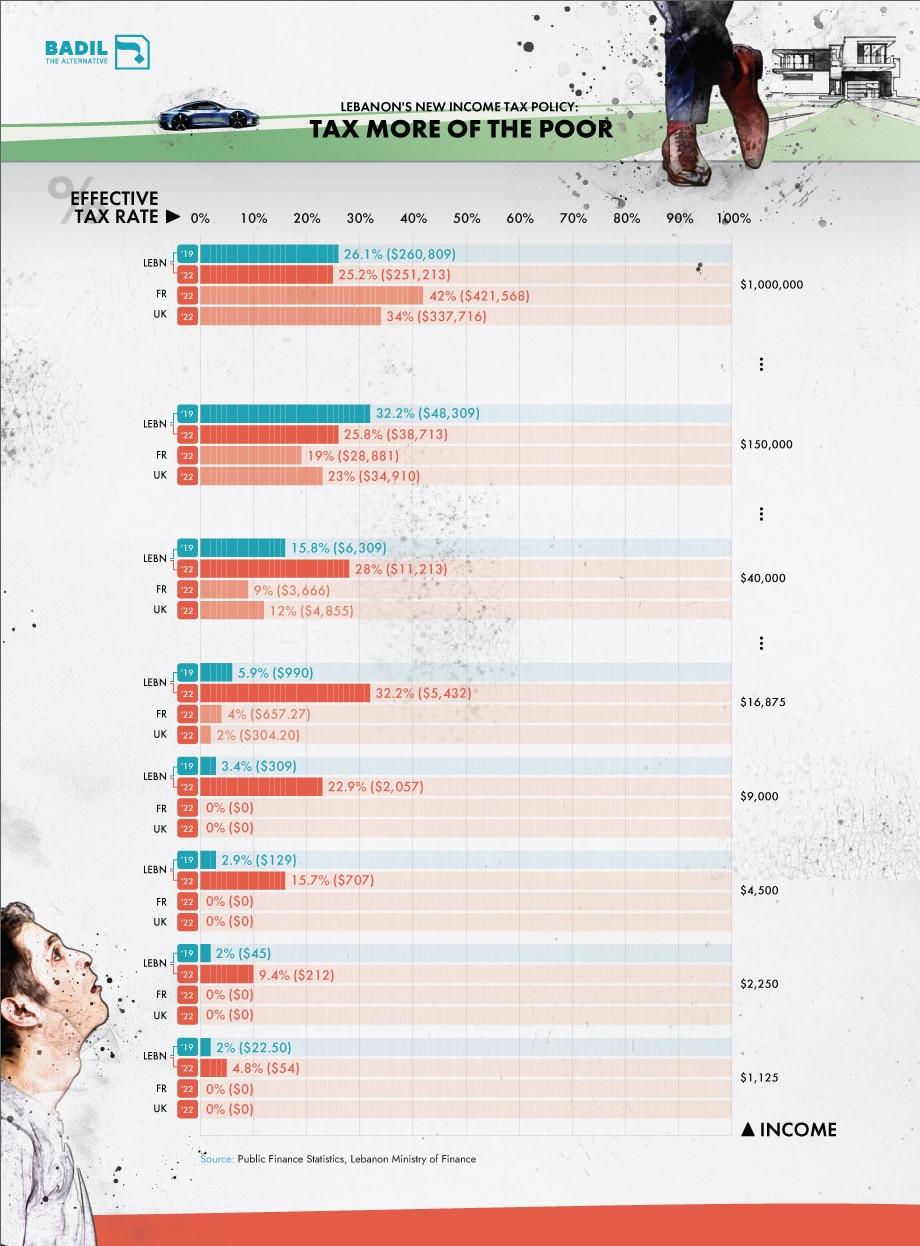

For most people there are only two certainties in life: death and taxes. In Lebanon the wealthy really only need to worry about the former. The state’s exceptionally weak tax and revenue structures mean the tax burden largely falls upon middle and lower classes – while the wealthy have a multitude of options to avoid paying taxes.

Revenue generation through tax collection is a fundamental pillar of a state’s social contract, and it is no accident that Lebanon’s contract has been built around a free-pass for the wealthy, and poor execution of the contract for everyone else.

Lebanon’s tax structure has positioned national incomes as some of the most inequal in the world, where the top 1% richest adults receive around 25% of the total national income.[1] This must change, not only from a moral point of view, but also from an economic one. Over 80% of the population now live in poverty – there is no more that can be extracted from the Lebanese middle and lower classes. At the same time, Lebanon’s patchy and uneven tax regime misses huge opportunities to collect revenue from the wealthy, who are among the few who can still afford to pay taxes.

The entwined elite business and political classes of Lebanon of course see no incentive in changing this structure, yet for the country to ever get back on its feet, taxes must be collected from those who can afford to pay them. This is not only critical for the financial health of the country, but also for reconstructing the Lebanese social contract, at a time when citizen bonds to the state are at risk of total dissolution.

Triangle has compiled data on the breakdown of Lebanon’s tax structure and revenue trends which maps a path towards returning Lebanon to equitably collecting 20% of GDP in revenues. These measures focus on picking the low-hanging fruit of more efficient tax collection, clamping down on rampant tax evasion by individuals and corporations, and restructuring major taxes such as VAT (Value Added Taxes) and income tax to be more progressive and in line with OECD standards. At the same time tax incentives need to be tailored to Lebanon’s private sector context, which is dominated by micro and small enterprises, as well as a huge proportion of informal labour.

The system of ‘pay little – get almost nothing’ has already come apart. Yet, the establishment is already working on building a new structure whereby regressive indirect taxes coupled with weak enforcement continues to form the bulk of state revenue. Botched banking secrecy reform, the customs dollar, new income tax thresholds are just the latest measures. For those who seek true reform and replacement of the same establishment, tax reform can no longer be a fringe issue, ignored because of its wrongly perceived technical nature. It’s not that complicated. Tax reforms need to be at the core of how Lebanon gets out of its predicament. If that means all Lebanese pay a little more for better services, while those who have the most bear most of the burden, then so be it.

Deliberately Poor

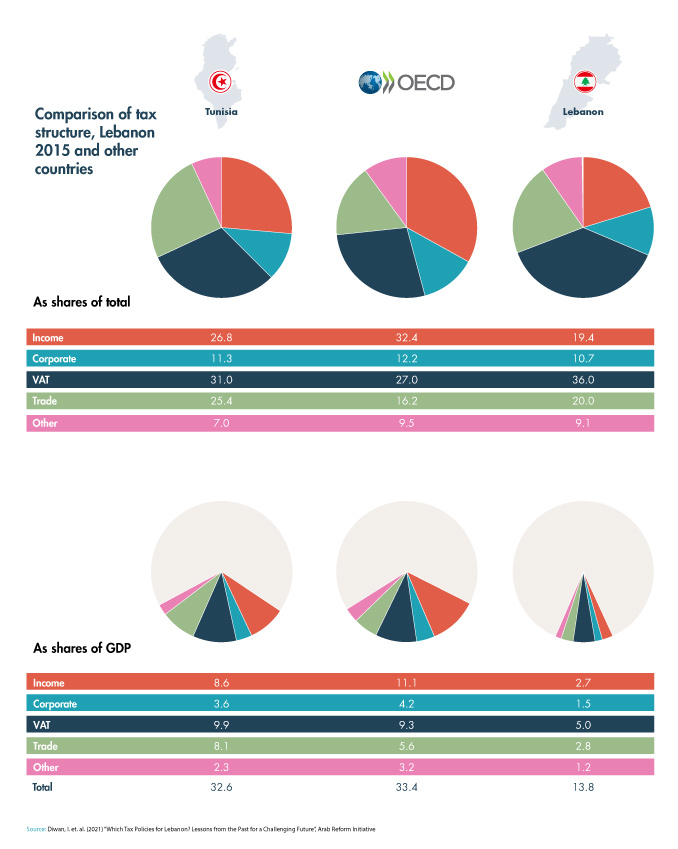

Prior to 2019, Lebanese government tax revenues only comprised 15-16% of GDP – lower than poorer countries such as Morocco and Tunisia.[2] The structure of tax collection has for decades been characterised by (among other things) a remarkably low top-tier income tax of 25% (which it only reached in 2019), weak tax collection systems, banking secrecy laws which protect tax evasion, and a heavy reliance on indirect regressive taxes such as VAT – which affect the poor more than the rich.

Lebanon has a much higher proportion of indirect taxation than OECD nations, and a remarkably low rate (11%) of revenue collected through progressive taxes. Low-income taxes and low corporate tax rates mean Lebanon collects two to three times less progressive taxes than, for instance, all of Africa on average.[3]

In practice, a low-income country means the state lacks (or chooses to lack) the resources to adequately fund essential social services, and instead leaves those fields open for the private sector to turn into profit-seeking opportunities. Often in Lebanon that means informal service providers with political protection, such as the infamous generator mafia which provides essential energy to most of the country. Whether officially, such as in education, or by de facto poor performance such as in electricity, the extremity of Lebanon’s social contract – pay little and get little in return – exposes lower and middle classes to paying a higher proportion of their income to access services from the informal, untaxed, and politically connected suppliers. By design, poor provision of public services also pushes poorer classes toward reliance on political patronage to access services at a more affordable rate.[4]

Weak revenue collection on its own is bad enough, yet in Lebanon the state has also been consistently spending beyond its means. The political class’s carrots and sticks game for popular support also means state resources – such as civil service employment – have become a common form of patronage endowment. For example, Lebanon has witnessed bloated teaching recruitments leading to a very low student-to-teacher ratio of 12:1 in 2017[5], despite continuing to have poorer than average learning outcomes.[6]

Salaries and other long-term bleeding holes in state expenditures such as Electricite Du Liban (EDL) transfers have meant expenditures have consistently been in excess of revenues. Instead of collecting adequate amounts of tax to cover these expenditures, the state chose to bet on a continuing supply of foreign currency flowing into bank coffers, combined with borrowing from banks and Banque du Liban (BDL). This scheme saw Lebanon accumulate one of the world’s highest debt-GDP ratio’s before 2019 and was a central factor in the 2019 financial collapse.[7]

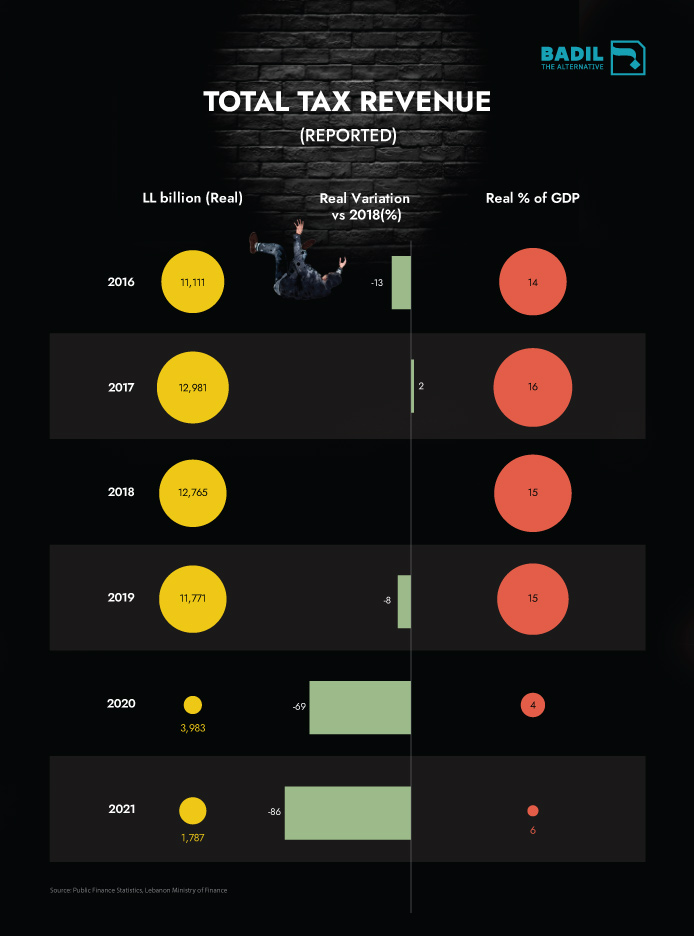

Weak budgets getting weaker

Since 2019 the Lebanese Lira (LL) has devalued by over 90%, meaning that the value of state revenues has also plummeted. Triangle’s calculations show that after accounting for inflation, total tax revenues have declined by 86%. This has left state revenues at a measly 6% of GDP, and poses an even tougher challenge for the government to resurface from the current financial crisis. Government printing of the Lira to cover its deficits – and to “Lirafy” the value of US dollar deposits – in the banking system has so far only led to rapid inflation and the degradation of the value of savings.[8]