Executive Summary

Lebanon’s economic crisis has spared few. Amongst the collapse’s cruellest blows has been the wholesale destruction of retirement savings, many of which were held in pension schemes run by Lebanon’s various professional syndicates.

Throughout their careers, many Lebanese workers relied on their syndicate pension fund to provide a vital nest-egg for retirement. Unlike younger generations, elderly Lebanese cannot even hope to rebuild savings that the nation’s bankers have squandered, having reached the end of their working lives.

Syndicate pension plans comprise a huge share of the total savings embroiled in the banking sector’s collapse. Despite the lack of publicly available data, Lebanon’s pension schemes have received contributions from hundreds of thousands of members over decades, amounting to billions of dollars in retirement savings.

These funds should have offered retired Lebanese workers in many fields the ability to support themselves financially in a country with scant social protection networks. Instead, banks have refused to allow syndicate pension funds to access their savings in full, imposing an unlawful capital controls regime over the funds’ collective deposits.

While Lebanon’s bankers remain the sorry affair’s central villains, syndicate leaders have been caught fast asleep at the wheel. Until the end of the civil war, syndicates and unions had vociferously represented their members’ interests on several occasions. Since then, decades of flawed administration and political co-optation have crippled syndicates’ once-strong performance, including their management of members’ pension schemes.

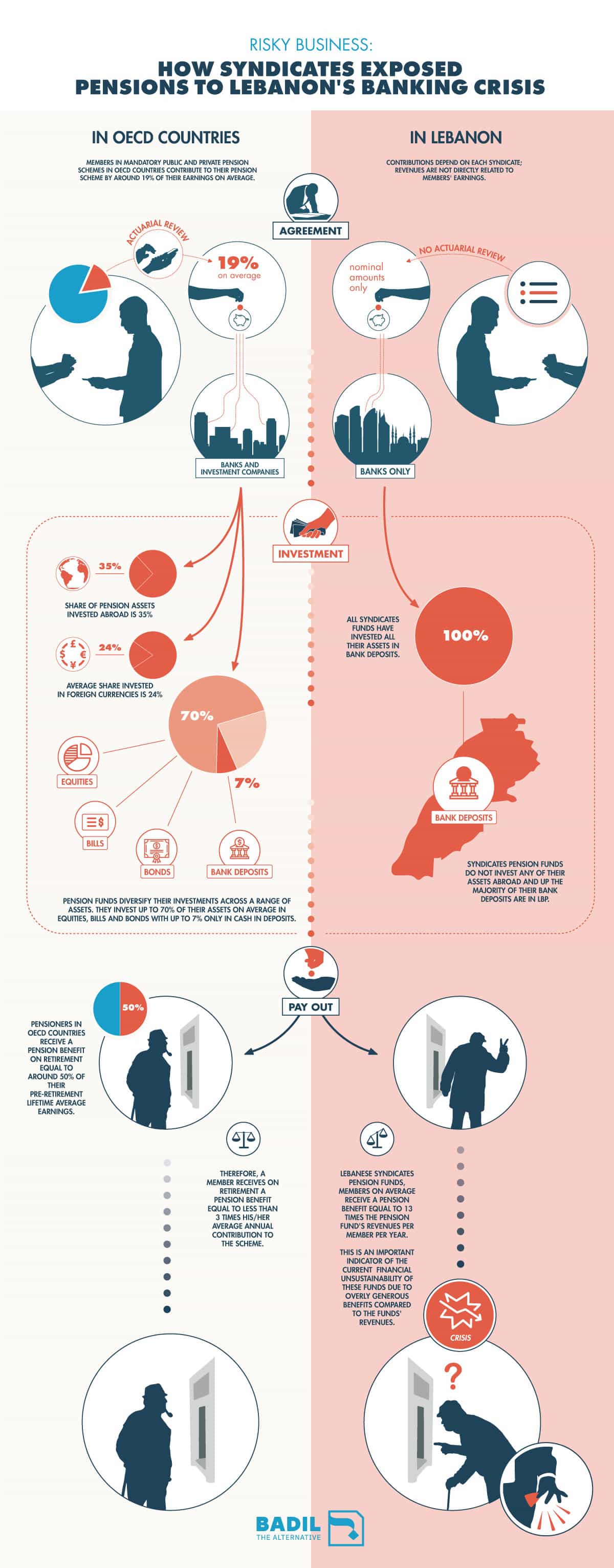

Syndicate leaders had left their members’ savings hopelessly exposed to the banking crisis by investing overwhelmingly in Lebanon’s commercial banks, against global best practice for diversifying assets. Further, even before the crisis, pension schemes were already offering unrealistically generous retirement benefits, making the funds financially unsustainable.

Without delay, Lebanon’s many syndicate members must band together to salvage their existing retirement savings. This effort will require participating heavily in upcoming IMF negotiations, to ensure that politico-banking elites do not use pension contributions to help write off their debts.

Syndicate members should create a new, united front for these negotiations, given the deep political co-optation of syndicate leadership positions since the civil war. Those same leaders, many with blatant conflicts of interest, cannot be relied on to defend members’ retirement savings against Lebanon’s ruling class.

Moving forward, syndicates will also need to take a hard look at their pension schemes, which are in desperate need of comprehensive reforms. Syndicate regulations do not require that sufficiently qualified professionals wield control over pension schemes, which has allowed flawed fund structures to develop over time.

From now on, all syndicates must require that qualified actuaries re-design pension schemes, making them financially sustainable. Asset management experts should also be charged with investing members’ contributions in line with international standards. These essential reforms will help safeguard the savings of Lebanon’s syndicate members against future shocks, ensuring that they do not find their pockets empty upon retirement.

NOTHING SAVED FOR A RAINY DAY

For hundreds of thousands of Lebanese, syndicate pension plans have long offered their primary financial support during retirement. Lebanon’s syndicates are organized groups of professionals, usually from the private sector. Members work as doctors, engineers, nurses and in other key professional fields. While these professionals must join their sector’s order to practice their profession, membership to a syndicate is optional. Many workers nevertheless choose to join syndicates to receive pension payments and other retirement benefits, such as healthcare coverage.[1] Syndicate pension funds perform an especially vital role in Lebanon, where the national social protection system is mainly characterized by low coverage and poor coordination.[2] Over time, the value of syndicate pension funds has grown significantly; an actuarial estimate suggests that the Engineers’ Syndicate alone had accumulated around $240 million in savings since the 1960s. While many of the larger syndicates contacted by Triangle refused to share the amount of their pension fund reserves, it is believed billions of dollars are now trapped in Lebanese banks.

With the onset of Lebanon’s financial crisis, syndicate members have lost access to this vital source of retirement income. Lebanese banks, with the support of the Banque du Liban, have placed illegal capital controls over their customers’ accounts, including money deposited by syndicate pension funds. To date, syndicate pension funds have not received a “special status” designation, which would allow them to bypass capital controls, despite the crucial importance of pension savings to many Lebanese households. To make matters worse, syndicates have placed most of their members’ pension contributions in Lebanese Lira-denominated accounts, whose value has plummeted due to the local currency’s sharp devaluation. Yet even US dollar accounts remain beyond the reach of syndicate members, given severe restrictions on foreign currency withdrawals under the capital controls regime. Accordingly, syndicates pension funds have been unable to disburse benefits or pay operating expenses. Thus members who were already receiving benefits, through no fault of their own are suddenly unable to support themselves financially in retirement.

Now, syndicate members must prepare for upcoming IMF negotiations, which will likely determine how the losses of Lebanon’s financial sector are allocated. [3] Earlier rounds of talks had broken down in 2020 mainly due to a disagreement over a unified figure for the financial sector’s losses.[4] But the question remains: who will pay for the huge losses caused by the economic crisis? The banks or the depositors, including pension funds? To decide on the distribution of losses, the IMF is expected to engage with major stakeholders – amongst whom should be the syndicates, given the enormity of their collective deposits with Lebanese banks.[5] Syndicates need to seize the opportunity and act now, before it is too late.

HOW WE GOT HERE: FLAWED ADMINISTRATION

Unfortunately, syndicate pension funds must share some of the blame for their members’ current predicament, following decades of flawed management and administration. Syndicate members did not realise that they were relying on financially unsustainable pension schemes for their retirement – a grim reality that applied long before the current financial crisis.

The syndicates’ unsustainable financial decisions stemmed from long-standing bad governance. The leaders governing syndicates relied on inefficient management structures for members’ pension funds. The syndicate’s president, along with the fund’s board of directors, are elected every two or three years and assigned the responsibility to manage all the operations of the fund, while the fund’s senior management team have no executive powers. This governance structure compromises the capacity of syndicates to manage their members’ pension funds effectively, given the high turnover of decision-makers. Moreover, many syndicate leaders have close ties to Lebanon’s politico-banking elite, creating a blatant conflict of interest with the leaders’ fiduciary duties to syndicate members (See below, “Political Co-Optation: The Hurdles Ahead”).

Poor scheme design

A well-administered pension scheme requires that members contribute enough money during their careers to allow the fund to distribute benefits to them upon retirement. In countries within the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), members of mandatory public and private pension schemes contribute an average 19 per cent of their earnings into the fund; then, when members retire, they receive payments equivalent to around 50 percent of their average, pre-retirement salaries.[6] As a result, each retired member receives a pension benefit equal to less than three times their average annual contribution to the scheme. This balanced approach ensures both that members can afford to meet their contribution obligations while working, and that the fund has enough money to make disbursements to all members.

Over decades, Lebanese syndicates designed pension schemes that promised unrealistic benefits to members. All the syndicates’ private pension schemes are “defined benefit” schemes, which give members a fixed amount of money upon retirement. Crucially, a defined benefit scheme does not calculate disbursements based on the amount actually contributed by members throughout their careers. Unlike average subscribers to OECD pension funds, Lebanese syndicate members were promised an average pension benefit which, according to Triangle’s calculations, was 13 times larger than their average annual contribution.[7]