EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

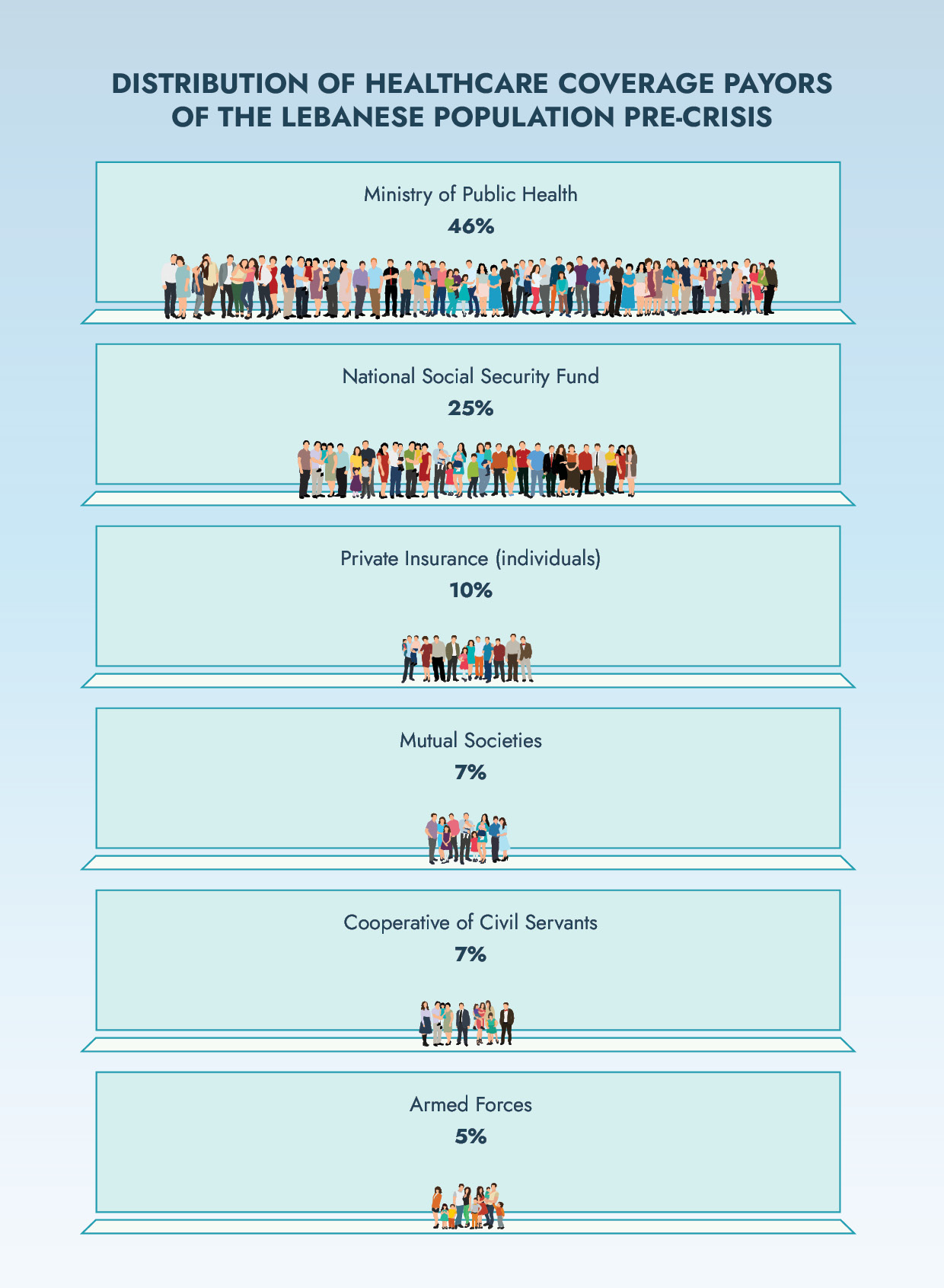

Amidst Lebanon’s economic crisis, it has become unaffordable for most people to get sick. Across the country, ordinary Lebanese can no longer afford to pay medical bills, which are now almost entirely denominated in cash US Dollars. Even before the financial crisis, about half of Lebanon’s population was not covered for health care, whether private or public.1 Yet the alarming lack of coverage even extends to most people with insurance. State-run schemes, including the National Social Security Fund (NSSF), can no longer afford to cover overwhelming medical costs in foreign currency. Households now face grim choices for their ill relatives, staring down financial ruin or fighting illness unassisted.

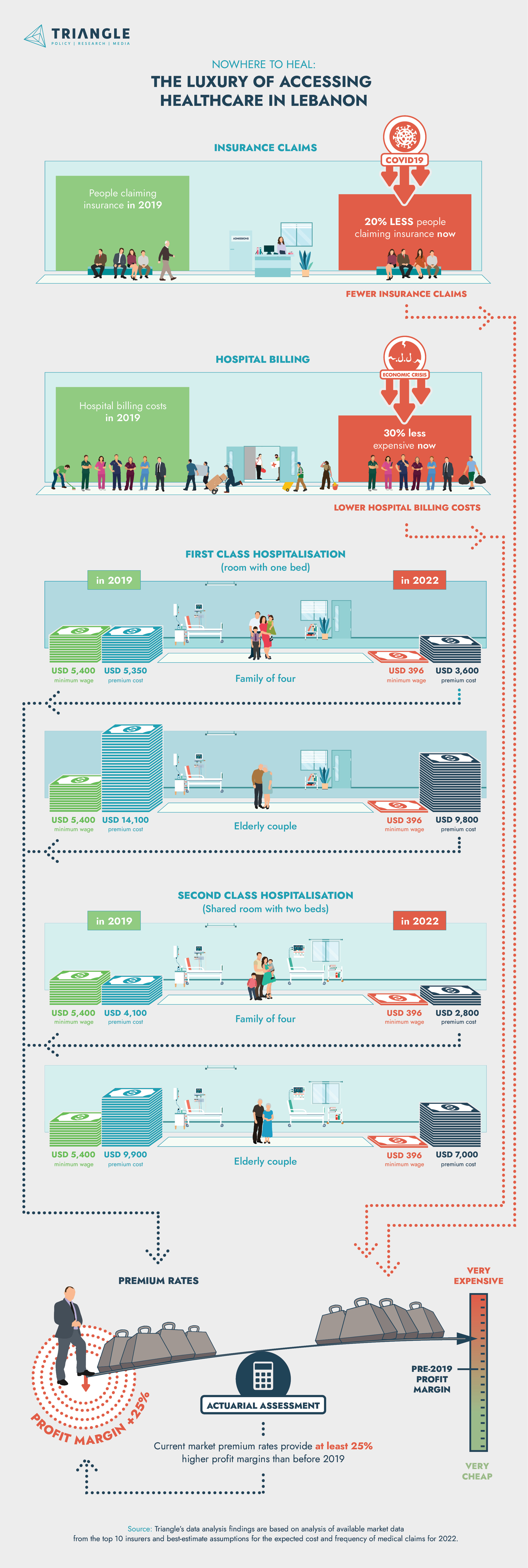

To make matters worse, private health insurance – the country’s sole remaining source of basic healthcare coverage2 – has become even more exclusive than ever. In the absence of adequate industry regulation, some policyholders who thought they were insured, found themselves paying large out-of-pocket expenses for hospital treatment for which they were covered in Lebanese lira. But the pricing tango between the hospitals and the insurance companies is coming to an end. As of May 2022, private hospitals will only accept patients who can pay for their bill in cash USD, to meet the hospital’s expenses. Following suit, insurance companies are moving towards fully dollarizing the industry. Yet, in another twist of the knife, Triangle’s calculations have found that insurance premiums are now on average at least 25% overpriced.

In truth, however, Lebanon’s healthcare collapse has merely lain bare systemic deficiencies that went unremedied for too long. In the 1960s, Lebanon introduced the NSSF with the aim of providing universal health coverage. By the time that the country emerged from civil war during the 1990s, state-run healthcare schemes had been hollowed out, providing woeful safety nets and scant coverage. Instead, post-war Lebanon relied unhealthily on private health insurance providers and mutual funds, which catered to the wealthier in the country. For many Lebanese, fearing medical bills is not a new phenomenon – the stakes have just risen even higher.

Lebanon needs immediate solutions for the healthcare coverage vacuum. At the present moment, private health insurance sector, despite its glaring deficiencies, offers the only viable option for ensuring basic access to healthcare. The government must regulate insurance companies to expand coverage under private schemes, especially by facilitating greater product diversification and enhanced market monitoring tools. The state should also introduce an expert independent committee to study pricing practices amongst insurers and reduce taxes on insurance products, which currently drive up premium rates.

Ultimately, Lebanon has no long-term alternative to implementing a comprehensive universal healthcare system, which at last consolidates Lebanon’s fragmented health sector. It is a right that must be worked towards urgently, especially given the public health challenges that lay ahead, such as the country’s aging population and high rates of chronic non-communicable diseases.3 With this system in place, private insurers can assume their proper market role: a luxury, supplementary product for consumers who are willing to pay extra for specialised care. Only then can Lebanon credibly claim to treat access to healthcare as a basic human right, as opposed to a plaything of the privileged few.

FROM HUMAN RIGHT TO LUXURY

By 2022, a longstanding, disturbing reality has become undeniable: in Lebanon, basic healthcare is now officially a luxury. The country’s unprecedented economic crisis has gutted key medical coverage sources on which most Lebanese previously relied. By mid-2021, Banque du Liban (BDL) could no longer provide importers with US dollars for medical equipment and supplies, and medications.4 As a result, hospitals and ambulatory care centres started demanding payment partly in Lollars, partly in cash US Dollars. This policy has exponentially increased medical insurance claim expenses since medical equipment, supplies and medications account for a large percentage of those expenses. At the same time, the Lebanese Lira’s (LBP) devaluation has slashed the true value of LBP deposits that bankroll the public NSSF, as well as targeted schemes for public servants and military staff. Dependents on these state-run schemes must now pay out-of-pocket health expenses, with their source of insurance now reduced to very little. Of course, the same financial hardship faces the half of Lebanese who did not have any healthcare coverage before the economic crisis, and must now desperately seek funds for treatment. Yet, in the current financial climate, these funds are becoming increasingly hard to get for low-income families, whose wages are now a fraction of what they used to be.

Lebanon’s economic collapse has also impacted the one potential source of continued basic healthcare coverage: private health insurance. Before October 2019, less than 20% of Lebanese relied exclusively on private insurers (including mutual funds) and around 10% benefited from complementary private coverage to the NSSF (CO-NSSF). There are currently 48 licensed private insurance companies whose total medical portfolio amounted to USD 526 million pre-crisis.5 The market is highly concentrated, whereby the top 10 insurers have control of 80% of the market premiums. As the economic crisis took hold, many problems arose between insurers and medical providers about billing arrangements. Private insurance companies started adopting unorthodox approaches to compensate for the rise in medical costs through multiple currency exchange rates. Instead of taking the responsibility of managing the risk, some insurance companies illegally shifted the burden onto their policyholders who, legally, should have been fully covered – regardless of currency fluctuations. Some insurers started asking their customers to pay a certain portion of the premium in USD cheques, which quickly rose to 100%. The private health insurance sector – already the preserve of wealthier Lebanese before the crisis – had become even more exclusive.

Accordingly, Lebanese private health insurers have continued pricing their products as luxury items, without indexing premium rates for inflation. Before the crisis, a middle-aged family of four would had to fork out three quarters of the minimum wage – 675,000 LL per month – for second class hospitalisation cover.6 The situation grows even more depressing for elderly couples, which face greater average health risks and therefore must pay higher insurance premiums. For the same in-hospital and outpatient coverage – covering about 85% of the cost of ambulatory care – an elderly couple, aged 75 and 65 respectively, would need to spend almost two times the minimum wage.