EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In recent years, Lebanese opposition movements have failed to successfully compete with the country’s establishment, sectarian parties. The latest parliamentary elections, held in 2018, underscored this political impotence. Ahead of the polls, the establishment parties faced a tide of turning public opinion, as popular anger rose over decades of state neglect and mismanagement. Opposition figures and leaders featured prominently in large-scale protests, offering a non-sectarian alternative. The frustrated crowds seemed impressed, yet – when opposition parties ran in the 2018 elections – they won just one parliamentary seat.

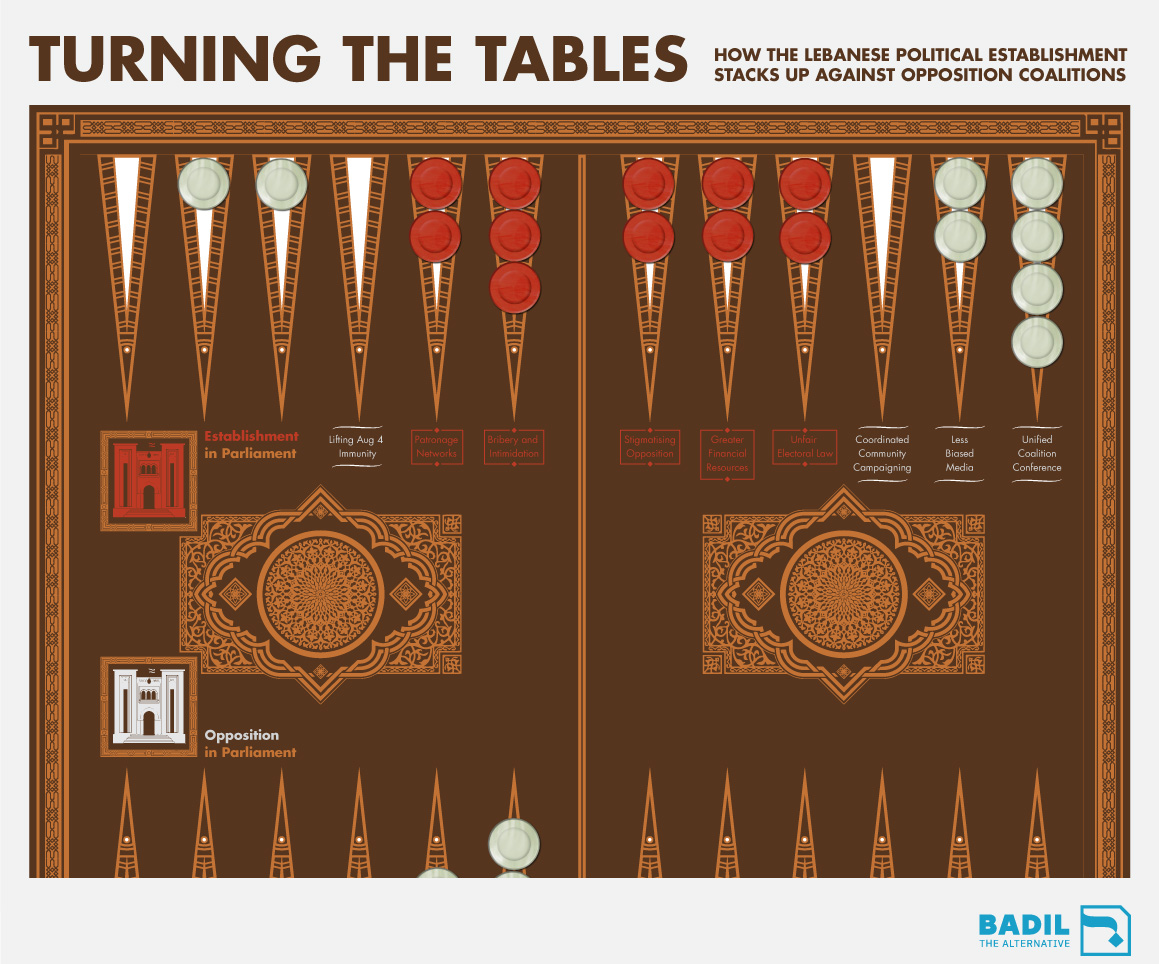

To be sure, opposition parties face intimidating, systemic obstacles when competing in Lebanese elections. Establishment parties have long benefited from a raft of unfair advantages in attracting votes. These factors range from the country’s crooked electoral laws, which allow sectarian parties to manipulate voter distribution, to more blunt instruments like bribery and intimidation. Sectarian leaders have also traditionally relied on extensive patronage networks, developed over decades, and dominance of legacy media in Lebanon. These challenges all contributed to the poor voter turnout for opposition groups in the 2018 elections.

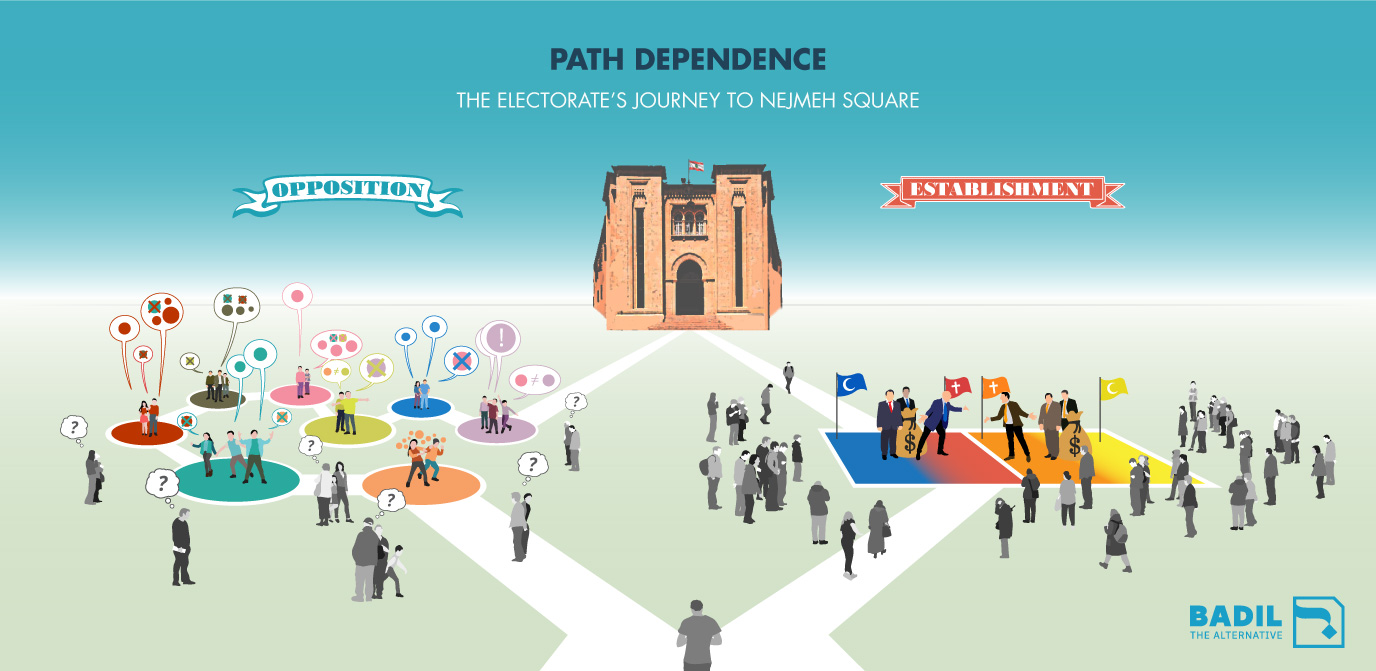

Nevertheless, Lebanese opposition groups must shoulder blame for failing to form effective, unified coalitions ahead of parliamentary elections. In 2018, non-establishment parties mustered only the belated, imperfect alliance Kulluna Watani, while long-term coalitions have remained elusive. Confronted with splintered opposition parties, voters struggle to understand what an opposition government would look like, and what policies it would advocate for. Moreover, the divided opposition parties ceded the opportunity to pool their human and financial resources against the well-resourced, slick electoral machines of Lebanon’s establishment parties.

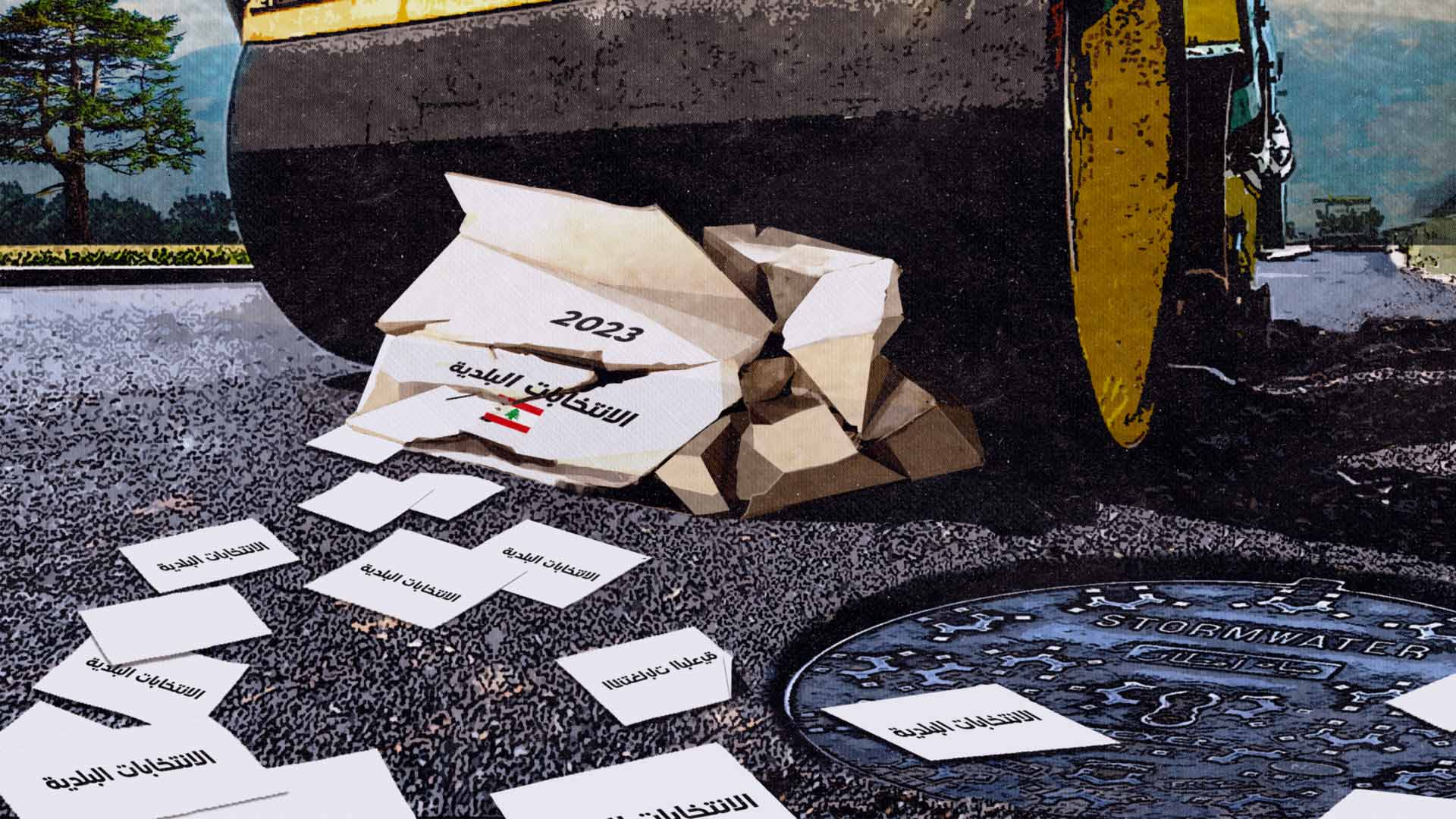

As Lebanon approaches another round of parliamentary elections, scheduled for May 2022, opposition parties face old threats and new opportunities. The establishment parties still enjoy some long-standing, systemic advantages like the biased electoral law and capacity for voter interference. Yet promising cracks have emerged in other traditional sources of the establishment’s electoral clout. Once-sturdy patronage networks have partially crumbled amidst Lebanon’s unprecedented economic crisis, which many blame on the country’s sectarian leaders. Various media outlets have started openly criticising establishment politicians and airing opposition perspectives, albeit within defined parameters for now.

Yet the opposition movement will almost certainly spurn these emerging openings without forming an effective coalition for the upcoming elections. Non-establishment parties acknowledge the necessity of presenting a united front and have started forming some alliances. The alarming fact remains, however, that the opposition movement still lacks a formal, unified coalition – with parliamentary elections a mere seven months away.

If the 2022 elections do proceed, the political stakes will be incredibly high. Form a united coalition, and Lebanese opposition groups stand some chance of gaining a potentially invaluable foothold in Parliament. Remain divided, and the country’s establishment political parties will almost certainly sweep the elections yet again, collecting thoroughly undeserved political legitimacy along the way.

WHO IS THE OPPOSITION?

By its nature, Lebanon’s opposition movement can only be identified by first demarcating the sectarian establish- ment that it opposes. Six main political parties dominate parliamentary seats: the Shi’a parties Hezbollah and Amal Movement, the Christian Free Patriotic Movement, the Sunni Future Movement, the Christian Lebanese Forc- es, and the Druze Progressive Socialist Party. Several independent parties and individuals also entered parlia- ment by forming electoral coalitions with the six main establishment parties.

For this paper’s purposes, the opposition movement encompasses the political parties that did not win parliamentary seats in the 2018 elections.1 This criteria for exclusion aligns with the “kellon yaani kellon” (“all of them means all of them”) label, which came to define the October 17 uprising as opposing the entire sectarian establishment. Under these criteria, this paper identified 23 political opposition groups that adhere to this criteria and received responses from eight: the Lebanese Communist Party, Beirut Madinati, LiHaqqi, Sab3a, Lubnan Yantafid, the National Bloc, Taqadom, and Tahaluf Watani. The paper also benefited from interviewing independent pressure support group Nahw al-Watan.

The difficulty in defining Lebanon’s opposition movement provides some early clues about the main challenges facing it. On a policy level, Lebanese voters face confusion about the ideologies and platforms that many opposition parties adhere to, not least because these groups have only recently formed. Procedurally, opposition parties have struggled to form broad coalitions amongst themselves, placing each party at an organizational and financial disadvantage vis-à-vis the establishment parties.

UNITE AGAINST THE MACHINE

For opposition parties, the 2018 elections demonstrated the crucial importance of forming effective coalitions to challenge the establishment parties. In May 2018, eleven independent and secular groups put forward 66 candidates in a unified electoral list called Kulluna Watani. The list contested nine of Lebanon’s 15 electoral districts but won only one seat. The coalition list was weakened by late preparation of the list due to arguments over alliances, a weak common agenda and insufficient local campaigning.2

A strong coalition would have improved opposition parties’ prospects of overcoming systemic obstacles facing new entrants to Lebanon’s parliament. First, establishment parties benefit from the skewed distribution of financial resources, which places opposition parties at a significant funding disadvantage. In 2018, legacy media – primarily television and radio stations – also favoured establishment parties by charging thousands of dollars per minute for interviews or appearances, putting these opportunities out of reach of most opposition groups.

Some opposition group candidates have gone into debt to finance their electoral campaigns; meanwhile, establishment parties have long hijacked state resources to fuel their patronage networks, or “electoral machines” (makanat intikhabiyye), that mobilise voters along electoral, financial, and sectarian lines.3 In this patently unfair contest, new entrants receive virtually no protection from Lebanon’s Supervisory Commission for Elections (SCE). The SCE is neither truly independent nor capable of imposing limits on campaign spending or auditing candidates’ financial reports.4,5 This lack of regulation heavily favours establishment parties, which reportedly flouted official spending limits during the 2018 elections, while also bribing voters with direct payments.6