Lebanon’s banks played a central role in driving the country into the financial catastrophe it has endured since 2019, and yet to date they have avoided legal sanction, regulatory reform, and efforts to have them bear their fair share of the financial burden. Where, one might ask, are the politicians who should be forcefully pursuing legislation to hold the banks to account? The answer is that many are on the boards of directors and among the shareholders of these very same banks.

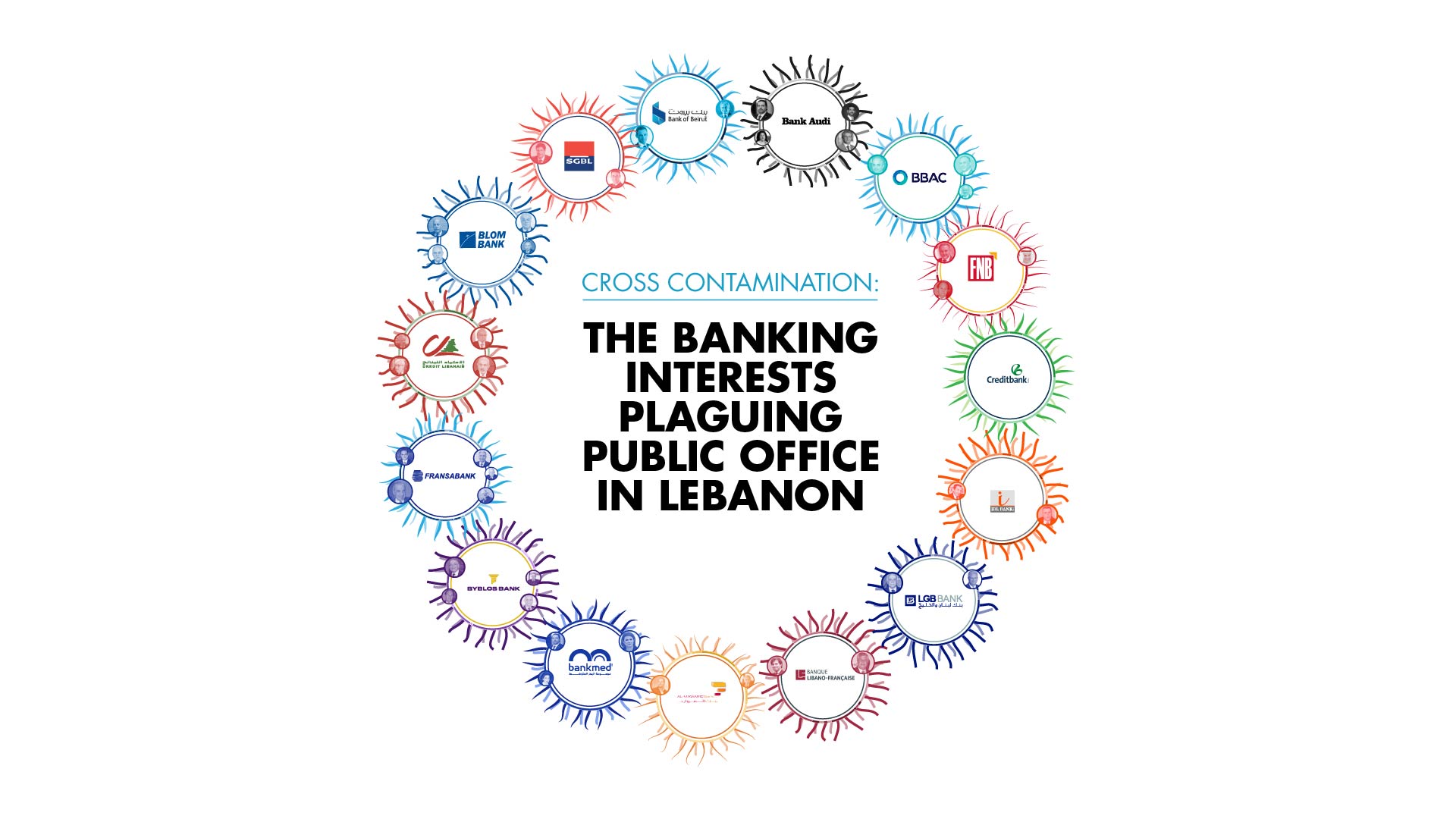

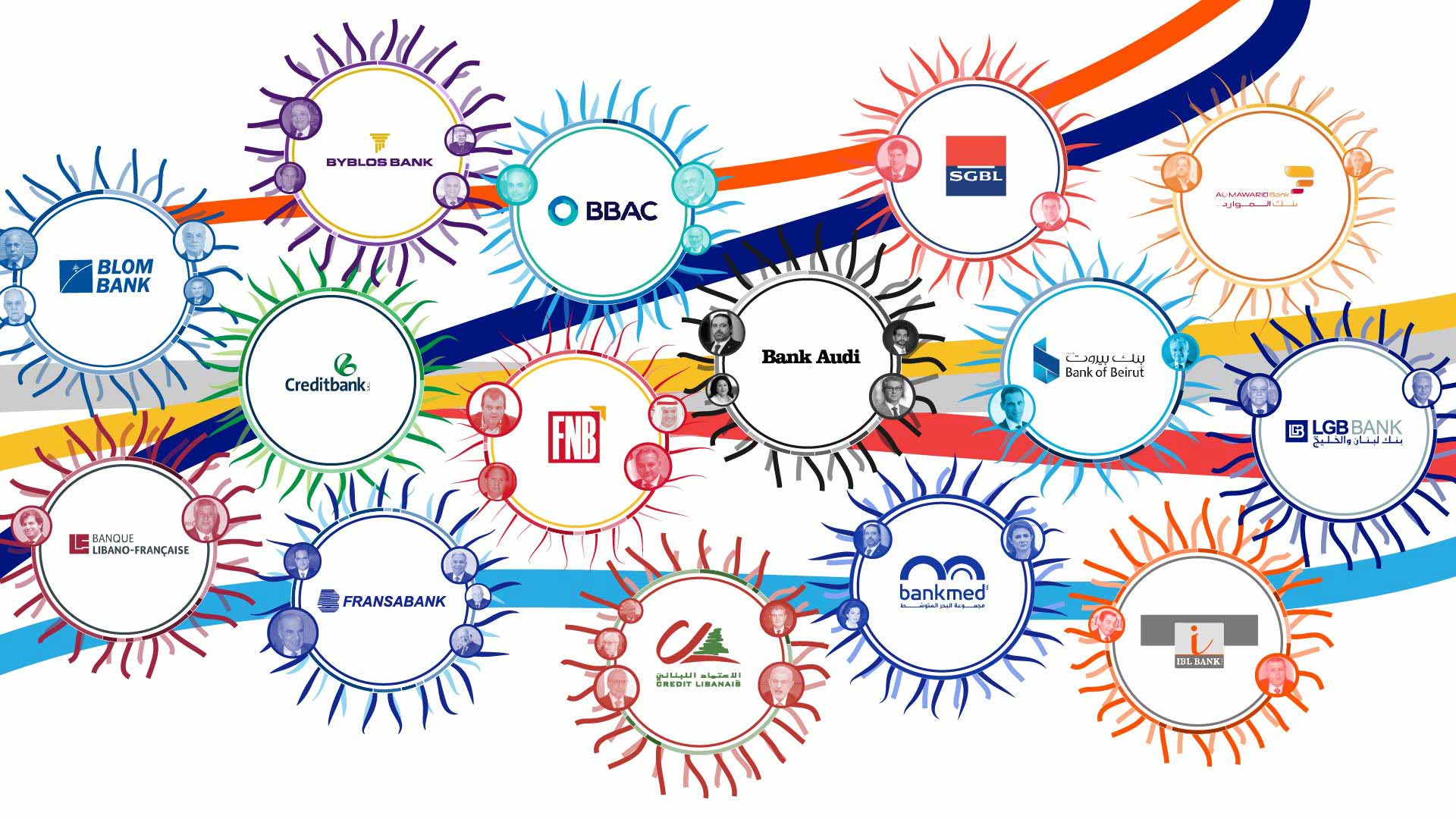

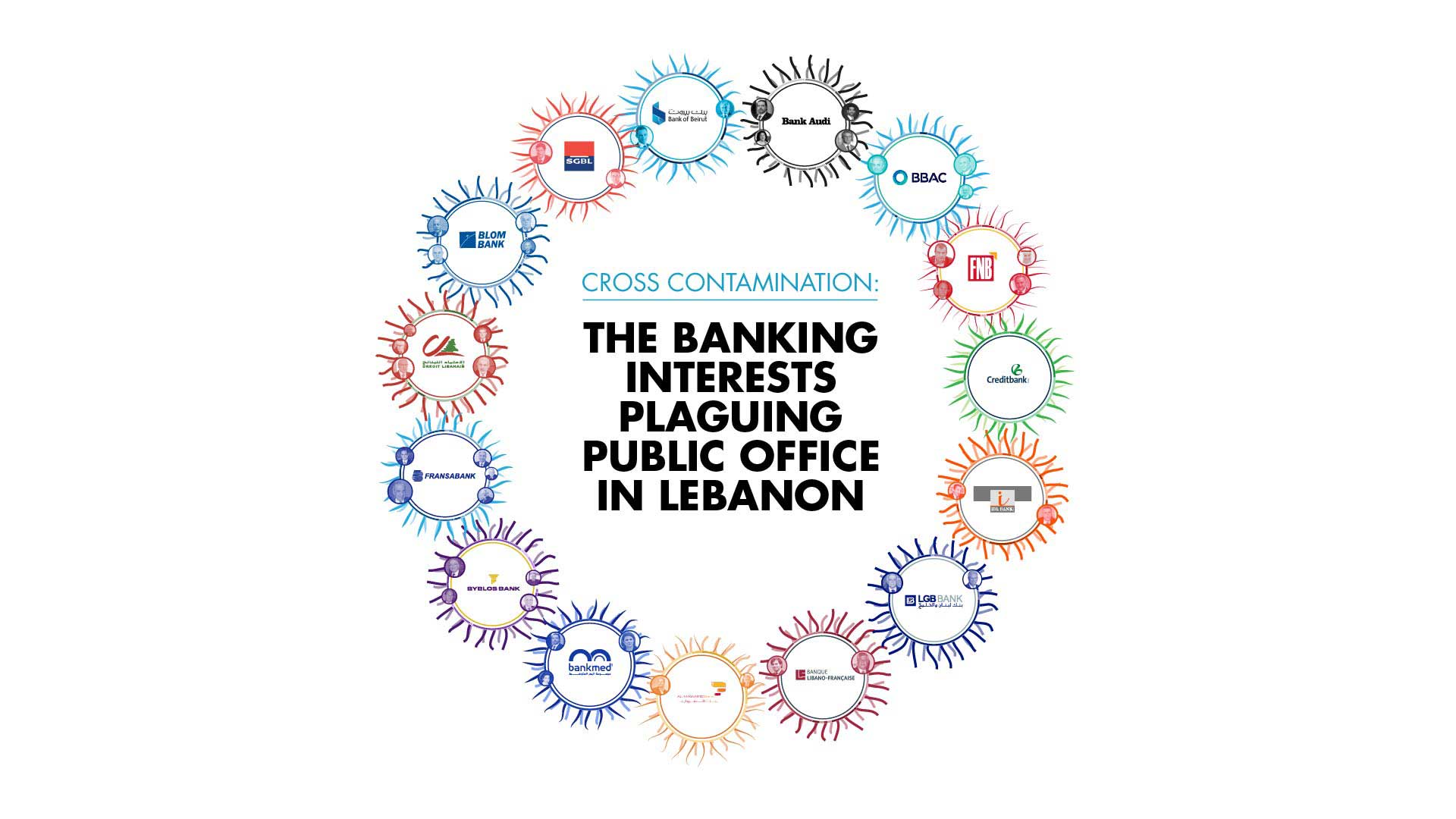

As The Alternative shows in this joint investigation of Lebanon’s largest 15 banks by assets, conducted in collaboration with the Depositors Union, there is a massive overlap between the country’s political class and those with financial interests in the banking sector. Indeed, as this report reveals, a quarter of all board members of Lebanon’s biggest banks meet the internationally recognized definition of a politically exposed person (PEP), meaning someone who either holds or has held a prominent public function, or family members and close associates of such people.

An example of the apparent conflicts of interest this can create was recently on display after Ghada Aoun, Attorney General at the Mount Lebanon Court of Appeal, filed charges of money laundering against Bank Audi, Société Générale de Banque au Liban (SGBL) and their senior leaders in February. Bank Audi is Lebanon’s largest lender, with assets in excess of LL40 billion, according to the Association of Banks in Lebanon’s (ABL) 2022 Almanac,[i] whilst SGBL is the country’s third largest bank.

Shortly after Aoun filed her charges, caretaker Prime Minister Najib Mikati intervened in the case, asking the interior minister to block the security forces from carrying out her orders. Mikati claimed that Aoun had overstepped her legal authority, while Lebanon’s Higher Judicial Council claimed Mikati had infringed upon the independence of the judiciary. Notably, among the many PEPs who are directors and shareholders at these banks is the caretaker prime minister’s own brother, Taha Mikati, who holds a 2.3 percent stake of Bank Audi.

Arguments over whether or not the financial stake that the caretaker prime minister’s brother and others held in these banks influenced his decision to block the investigation are less important than the clear fact that it could have. Najib Mikati, who has served as prime minister three times, has been entrusted with the authority to make decisions in the best interest of the Lebanese public. However, potentially hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of his brother’s investments are inherently among his private concerns. When these two interests overlap, as with Attorney General Aoun’s investigation, Mikati is no longer able to exercise the authority of his office without appearing to be compromised. A step Mikati could and should have taken to reassure the Lebanese public was to recuse himself and allow an independent and impartial third party to decide whether Aoun was acting within her remit. Mikati did not, and so we can only guess – did he act to uphold the statute of the law, or did he abuse his power to protect his family’s wealth?

As this report shows, across the country’s political spectrum and banking sector there is an entanglement of public authority and private financial interests. The country’s leaders continually oversee government decision-making regarding matters in which they have inherent personal financial interests.

This puts into question why, in the more than three years since Lebanon entered economic collapse, have all attempts from members of the judiciary to audit the banks and force transparency with their accounts been delayed or derailed from higher up the chain of command? Why, a year since Lebanon signed a US$3 billion bailout package with the International Monetary Fund, has the country not implemented the reforms necessary to release the money? These required reforms include a legal framework to redistribute losses from the financial crisis between the government, the banks and depositors, removal of bank secrecy in line with international norms, restructuring of the financial sector, and the implementation of formal capital controls – all of which would threaten the current impunity the banks enjoy.

This investigation by The Alternative maps the direct and indirect interests many in Lebanon’s political class have in the country’s banks, however, this is not in itself proof of wrongdoing or abuse of power. What it does prove, however, is that much of the current Lebanese leadership is in an inherent conflict of interest with regard to attributing fault for and plotting a path out of Lebanon’s devastating financial crisis. It is telling that our research found shared economic interests between so many shareholders, directors and the political class.

Those who are in conflicts of interest need to recuse themselves. If they do not, all means of international pressure should be brought to bear to oblige them to turn over authority in this regard to an independent and impartial third party. Such an entity would be empowered to investigate violations of Lebanese and international law and bring justice to bear where it is due. It is telling that our research found shared economic interests between many shareholders, boards of directors and the political class.

The Alternative contacted all of the banks mentioned in this report on multiple occasions prior to its publication to request comment. BLOM Bank’s Corporate Secretary, Mohamad Sidani, was the only bank representative to issue a statement. In it he wrote that the banking sector is “an essential pillar of any national economy” and protecting it from “defamation and false accusations” protects the national economy. He stated that it was the poor management of the country, rather than the actions of the banks, that spurred Lebanon’s financial crisis, and that BLOM remains committed to both “the highest legal and ethical standards” and “all applicable local and international laws and regulations”. Referring to the crisis period, Sidani said BLOM followed all ABL and Banque du Liban decisions to restrict foreign currency transfers, and “for the sake of ensuring fairness and equal treatment, BLOM BANK didn’t undertake any transfer of deposits abroad to members of its management, to shareholders, to politicians or to any related parties.”