For international EMT providers, Lebanon’s risk profile at a political and regulatory level make it unattractive relative to other countries in the region. For instance, in 2013, PayPal announced it would launch in Egypt and Lebanon. Yet today the company operates in Egypt, UAE, Jordan, Tunisia, Algeria, Bahrain, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen – but has yet to enter Lebanon.27 In fact, Lebanon is uniquely listed under PayPal’s prohibited countries due to “Persons Undermining the Sovereignty of Lebanon or Its Democratic Processes and Institutions” —wording that falls under restrictions imposed by the United States on the militia-cum-party Hezbollah.28,29

Lebanese money service businesses, as well as banks, have also been put under the spotlight by the United States for terrorist financing concerns under the Hezbollah International Financing Prevention Act (HIFPA) of 2015, and an amendment in 2018 (HIFPA II). In April 2019, the Chams Exchange in Chtaura was designated by the US Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) for connection to Hezbollah. Such designations, as well as tighter controls by correspondent banks outside of Lebanon, led to BDL putting restrictions on what transactions money service businesses can do, and limited foreign transactions to larger companies. As a result several money service businesses, and one of the five major companies, have closed down.30

While external pressures have had an impact, such as on PayPal, Lebanon’s regulatory regime, or lack thereof, is probably the greatest impediment to EMT service development in the country. Countries that have sound local EMT regulations, laws, and licensing serve to legitimise and protect an EMT company’s presence in the country, while strategic partnerships with local financial institutions helps ease the risk and process. When companies such as PayPal are in the process of entering a country, they often seek out bank partnerships or collaborations with central banks. In 2014, for instance, PayPal partnered with Jordan’s Cairo Amman Bank to provide services to the bank’s customers.31 Additionally, the Central Bank of Jordan sought proposals in 2012 from EMT and MMT companies to establish its national e-payment and mobile payment platform, JoMoPay, which was officially launched in 2014.32,33 No such thing has taken place in Lebanon.

Indeed, when compared to Jordan, Egypt and the UAE, it is clear that the BDL has not kept pace with the need to update EMT regulations. The only regulation governing EMTs in Lebanon is in the form of a circular, Basic Decision No. 7548, issued by the BDL in 2000.34 The regulation imposes basic requirements on financial institutions that wish to carry out EMTs in Lebanon, such as capital requirements and standards around anti-money laundering, and countering the financing of terrorism.35,36,37 However, these are standard regulations that do not directly target nor specify key aspects of modern financial technologies, not to mention those which facilitate the entry of EMT service providers.

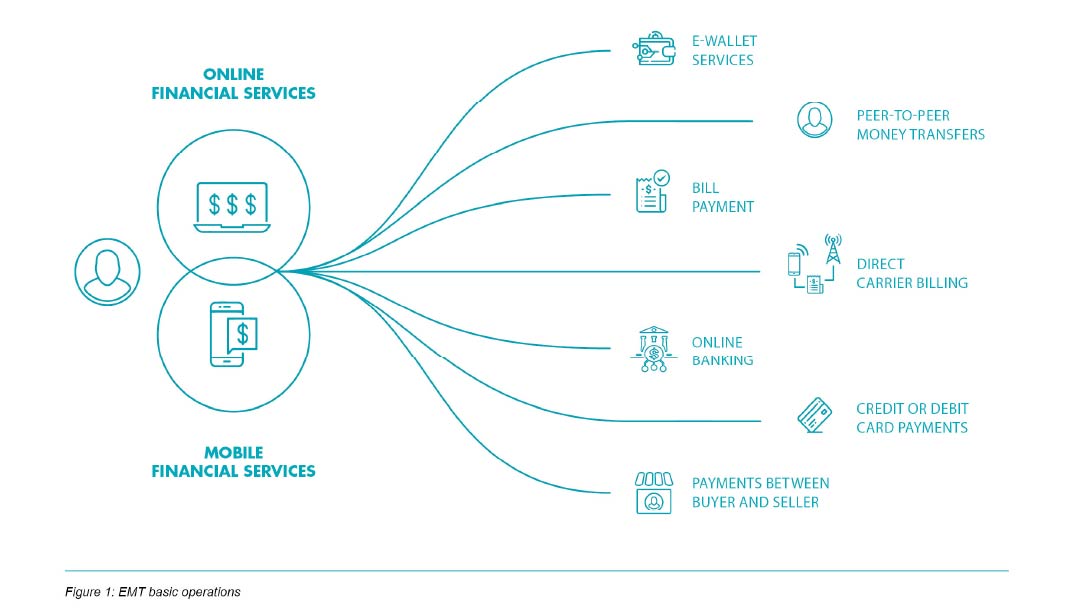

According to the BDL’s Basic Decision No.7548, EMTs are defined as “all operations or activities concluded, executed or promoted through electronic or photo-electronic means (telephone, computer, internet, ATM, etc.) by banks or financial institutions or any other institution’’.38

Moreover, it defines financial institutions authorized to conduct EMTs as “issuers or promoters of all types of electronic charge, debit, or credit cards; institutions engaged in the electronic transfer of cash; and the websites specialized in offers, purchases, sales, and all other electronic banking services”.39 This broad regulatory definition leaves much room for interpretation and fails to identify EMT or MMT services, thus resulting in legal uncertainties for those working in financial technology. Other countries in the region have faced similar issues, and resolved them.

The Central Bank of the UAE amended their regulations on EMTs to include and differentiate between both Payment Service Providers (PSP) and Payment System Operators (PSO), and went further to provide specific categories that fall under each.40 In the EMT regulatory architecture, such inclusions become necessary, not only to recognise these providers and operators, but also to provide specific and relevant regulations to manage their services in the country of operation. Under BDL regulations, it remains difficult to identify how non-banking services like Apple Pay or Google Wallet, or direct carrier billing services like Boku or Fortumo, would be legally classified. Lebanon’s only MMT service provider is a case in point: local company PinPay, which was bought out by Bank Audi and BankMed in 2011. PinPay faced several issues related to the lack of definitional clarity in the regulations. Since Lebanon has no definition for peer-to-peer EMT (electronic money transfers made from one person to another, typically through a payment application), there is no guarantee that all potential users of PinPay could legally make transactions to each other. Hence, even though the intention of the PinPay service as to offer users the ability to transfer money to their family and friends in near real-time using a mobile application, the two banks decided to only offer the service to their own customers, removing the opportunity for users to transfer money to those outside of their banking network.

To date, the BDL has only licensed PinPay, which has come to constitute both the exception and the rule when it comes to EMT in Lebanon. Indeed, PinPay’s license was exceptionally issued ostensibly because the two main shareholders were traditional banks, Bank Audi and BankMed, and vouched for PinPay’s solvency and respect of financial transactions security. Since then, no other license has been issued to any other online financial institution, meaning that de facto and de jure, the banking sector maintains control of EMT. 41

NEW LAW, NEW HOPE?

After nearly 14 years of gestation, the Lebanese government issued Law 81 on Electronic Transactions and Personal Data in late 2018, replacing Law 133 from 1999, and introducing into law electronic signatures and standards on data privacy protection in electronic transactions.42 Though implemented late in the game, Law 81 brings hope for new EMT regulations.

However, apart from providing for some much-anticipated consumer rights provisions —such as obliging financial institutions to notify them of any fees, expenses, commissions or taxes related to their electronic payments— Law 81 does not oblige BDL to update its Basic Decision No. 7548, from 2000, or to regulate the EMT sector.

Law 81, like the previous law, still devolves responsibility for licensing financial companies wishing to conduct EMTs to the BDL.43,44 As a consequence, any EMT service provider wanting to operate in Lebanon must first obtain the approval of the BDL – a lengthy and complicated process.45,46 For instance, companies need to provide detailed personal information for each employee, from their CVs to police records and bank statements and, last but not least, have their application signed by the governor of the BDL himself.47

LEBANON LOADING…

Lebanon remains far from where it should be in terms of EMT regulation and initiatives towards financial inclusion. Jordan has already launched a national e-payment and mobile payment platform specifically designed to address its cash-based economy. The platform has helped unbanked, low income Jordanians and registered refugee card-holders to have access to modern and affordable financial services.48 Notably, in 2016, the Central Bank of Jordan (CBJ) established the Digital Financial Services Council (DFSC) to address financial technology issues and establish reforms, highlighting the CBJ’s clear interest to develop the EMT and MMT industry in the country.49 Egypt, another cash-based economy, not only implemented specific regulations for mobile payment services in 2016, but also established a National Council for Payment (NCP) to address all subjects related to payments in the country.50,51 In the UAE, around 30 licensed EMT service providers offer mobile payment and mobile money transfer solutions.52 In 2017, the UAE Central Bank even issued a new “e-payment regulation” to facilitate the adoption of new payment service providers and operators in the country, as well as introduce the use of digital money (digitally stored value) to their payment methods.53

CONCLUSION

It is clear that central banks and governments around the region are pushing for the entrance and development of EMT, MMT, and other financial technologies to help their population (banked and unbanked) access affordable services. Lebanon’s banked population still reels from exorbitantly high fees, while those who have no interaction with the financial sector (around 53% of adults) could become financialised almost immediately if modern EMT services such as direct carrier billing were in place.54 Either by intention or design (or both), Lebanon, its central bank and its policy makers maintain a financial status quo that works in favour of the banks and a few financial institutions, putting their profits above Lebanese consumer welfare, yet again. If Lebanon is to continue to rely on decades-old regulations to organise the EMT sector, this situation will persist and the Lebanese will continue to suffer.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The introduction of modern EMT services would dramatically benefit Lebanese consumers by reducing associated electronic money transaction costs, and enable citizens to buy/sell goods and services to/from abroad. This, in turn, would stimulate the Lebanese economy, create jobs and spur an almost non-existent e-commerce market.55 The passage of Law 81 means momentum is building, and the introduction of EMT services should be a priority for regulators, financial institutions, policy makers, civil society and the general public. To help smoothen this path, the following recommendations target each of these groups.

Banque du Liban

The BDL needs to play its part as the key regulator of the EMT market. To do so, the central bank should institute detailed and clear definitions of EMT standards to allow consumers to make interbank transfers in near real time, from their computers or cellphones, and not only through the bricks and mortar banks. The BDL can easily emulate the models of the UAE, Jordan and Egypt, especially in terms of offering mobile payment solutions to the unbanked in the country.56

In the end, the BDL’s EMT regulations need more than just revamping, they require a clear identification of which financial institutions are allowed to conduct EMTs, the ways they can conduct EMTs, who is eligible to use these services, and all the rights and duties under Lebanon’s legal framework.

Update Decision No. 7548 to encourage the establishment of EMT service providers. At present, the regulations and definitions around EMT in the form of Decision No. 7548 are outdated and irrelevant for EMT service providers. This is particularly the case for EMT providers offering mobile payment solutions, those wanting to set up shop in Lebanon, and for Lebanese entrepreneurs wishing to enter the local market.

The Decision needs to be updated to include definitions of key service types (such as peer-to-peer), service operators, as well as simplified and reasonable requirements to fulfill in order to enter the EMT market.

Establish a national EMT and MMT service that is accessible to all – from citizens to refugees. Following the Central Bank of Jordan, Egypt, and the UAE’s initiatives for financial inclusion, the BDL should send out a request for proposals from EMT and MMT providers to develop a national platform that would be designed to specifically meet the needs of the country’s cash-based economy and large number of low income unbanked individuals. Paid for by international donors and local entrepreneurs in the field of financial technology, the platform should be affordable and easily accessible for all.

Establish a council for all EMT and MMT regulations. With the field of financial technology constantly evolving, a council should be established to monitor and address all issues related to EMT or MMT, as well develop further reforms that are needed to keep the BDL up-to-date on emerging services. The council should include both public and private representatives – not just those in the financial sector – and would help develop proper criteria for licensing, as well as provide opportunities for EMT and MMT businesses to share innovations to reform regulations.

Policymakers

Make EMT and e-commerce a defining part of Lebanon’s economy. The last 20 years have been characterised, in part, by a lack of coherent strategic planning and a failure to adapt the Lebanese

financial regulatory framework to the opportunities presented by modern financial technology. An e-commerce national action plan would give policy makers and the private sector the chance to present a coherent, forward-looking set of policies aimed at boosting financial technology start-ups, including those that provide EMT services. Additionally, policymakers should introduce policies that foster home-grown Lebanese EMT companies, and provide regulations that protect rather than deter these companies from operating in Lebanon.

The Ministry of Economy and Trade Consumer Protection Directorate — which aims “to attain modern consumer protection framework in Lebanon that safeguards consumers’ interests” — should also work to uphold standards by taking up its role as the protector of consumer welfare and push for modernised legislation that informs and protects consumers.57

Open up the market for international companies to perform direct carrier billing services and provide unbanked people in Lebanon with alternative forms of money transfers.58 Direct carrier billing services in particular would allow unbanked people to directly charge their payments and bills to their phone bundle, instead of having to link a bank account to their mobile application.

Banks and Financial Institutions

Reduce excessively high transfer fees at banks, abide by mid-market rates, and further develop services on the online banking applications for mobile phones. Banks and financial institutions will need to come to terms with the fact that they cannot continue to rely on exorbitant fees and commissions to drive non-interest revenue. Instead, these financial institutions will need to offer rates that are competitive and comparable to those offered by modern EMT service providers, while also improving their own services to increase financial inclusion through EMT market penetration.

This process will not only entail reducing fees, but also time constraints, and physical presence at the bank. If banks wish to keep pace with the fast developing FinTech sector, they should take an active role in FinTech startup investment. Banks should consider a range of investment models from debt to equity, as well as partnership strategies to help spur a sector that is in their intrinsic interest.59

Civil Society

Launch a campaign to bring modern EMT into the Lebanese market. Civil society actors who advocate for consumer welfare will need to create momentum for policy makers to support the rights of the Lebanese to access modern EMT services and not continue to be excluded from the global market. The campaign should have clear demands (outlined above) and lobby for clear statements from international companies explaining why they continue to avoid entering the Lebanese market so that these gaps can be addressed. To do so, a coalition of Lebanese consumer rights organisations, digital rights campaigners, media, and amenable public officials is recommended.

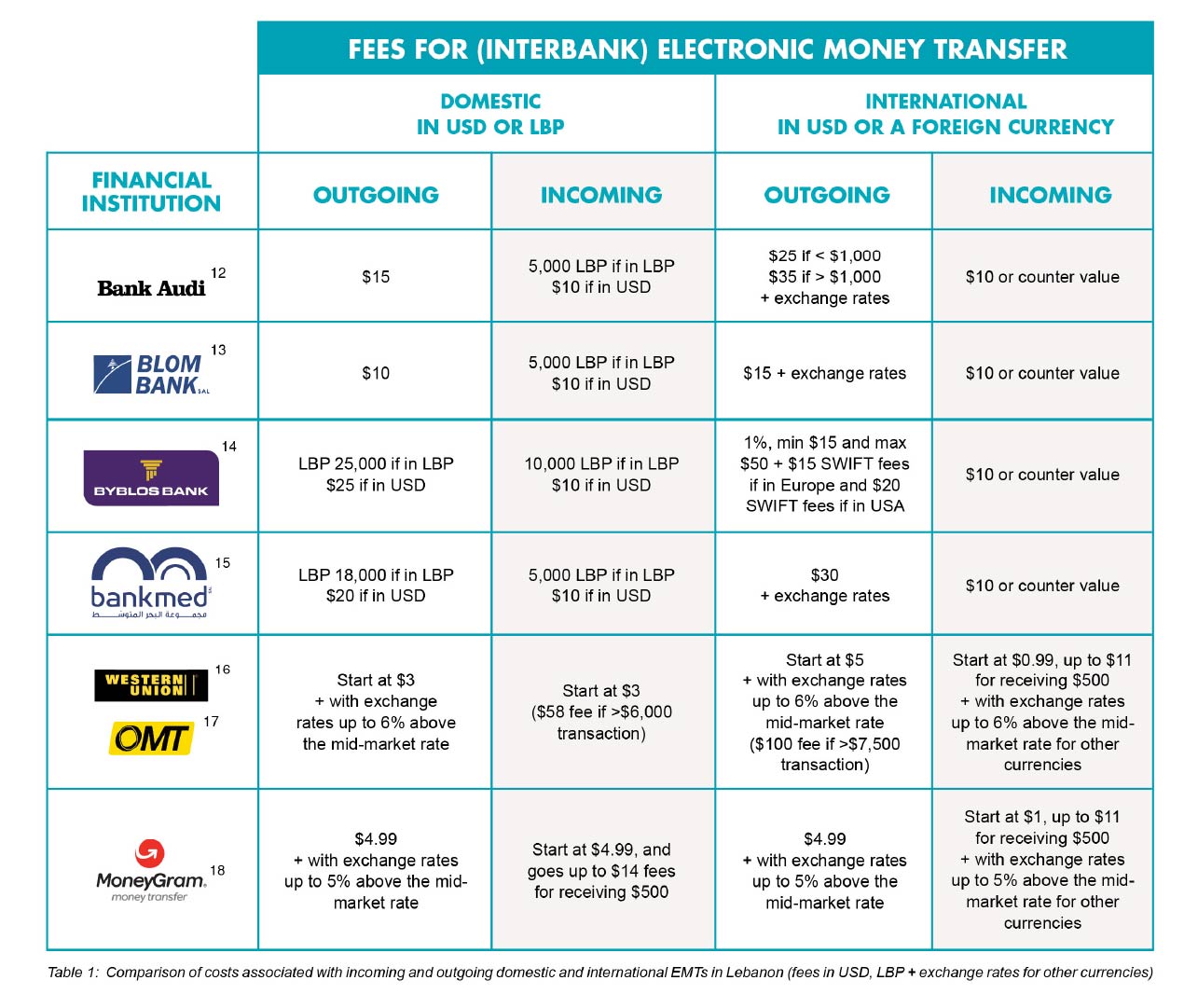

Lebanese consumers

Before making money transfers, research the rates offered by banks and other non-banking services such as Western Union. Charges will depend both on the amount of money being transferred as well as the currency it is transferred in. For example, sending USD 500 with Western Union would be less costly than sending it through a traditional bank – saving you up to USD 14 per transfer.60

If you’re lucky enough to own an overseas bank account, consider setting up an account with a mobile payment app such as TransferWise or Revolut. These apps allow you to send and receive money at extremely competitive rates, although they do not currently allow you to transfer money into them from a Lebanese bank account.

EDITOR’S NOTES

This policy paper is the result of research and writing by Justine Stievenard and Gina Barghouti.

Editing support was also provided by Charlie Lawrie, Sami Halabi and Paul Cochrane.