Unrestrained Urbanisation

According to Mona Harb, professor of urban studies and politics at the American University of Beirut (AUB), there is an urgent need for new public policy frameworks to guide the urbanisation planning processes.

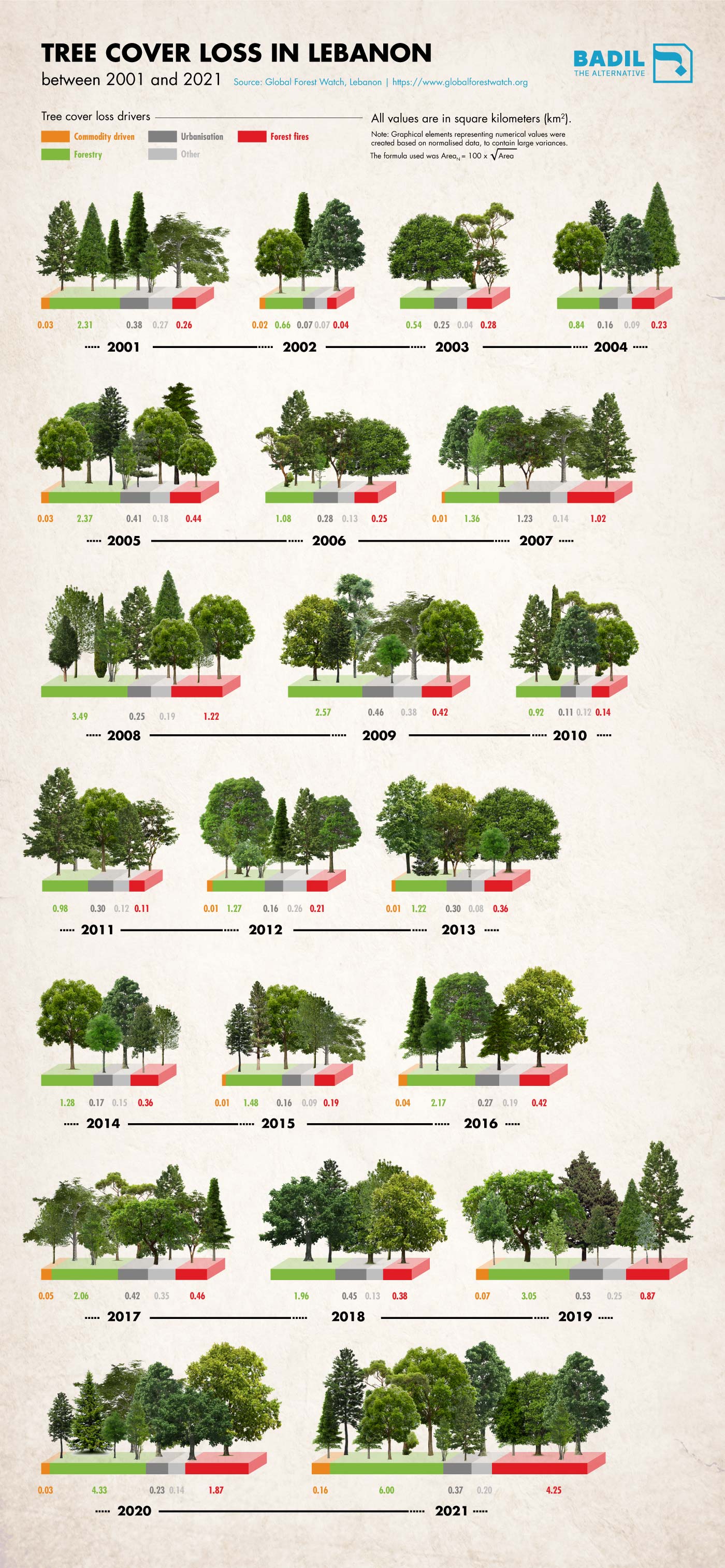

Since the end of the civil war, Lebanese economic policy has leaned heavily on the real estate sector to drive economic growth. Government legislation and central bank interventions facilitated investments from abroad – largely wealthy expats and Gulf investors – being channelled into the banking and real estate sectors. The intense construction and growth of cities in these years were matched by the urbanisation of rural areas through the growth of villages. Without effective state policies or plans aimed at regulating urban planning and protecting natural areas, much of this urban expansion came at the expense of wild grasslands and forests.

As Harb notes, while regulations exist, there is a fundamental gap at the implementation level. The “National Physical Master Plan for the Lebanese Territory” was endorsed in 2009, urging public and private stakeholders to address urban planning needs in local development. This document provides only guidelines and recommendations, however, without support laws and policies to give them regulatory force. Additionally, Lebanon lacks a unified body tasked with supervising and regulating urban planning matters, which currently overlap between many ministries and public agencies.

Actors involved include the Directorate General of Urbanism (DGU), the Higher Council for Urban Planning (HCUP), the Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR), and other sector ministries, such as the Ministry of Environment and Ministry of Public Work, among others. Coordination between these agencies is extremely limited at the moment, and, as Harb argues, it is very difficult for the situation to be regulated without a designated unit that can act as a link across these sectors being established.

“This is an intersectoral issue and cannot be thought about at the level of separate sectors and ministries” says Harb. She suggests that the responsibility for urban planning should be concentrated in either a regional planning unit at the level of the qada’ (province) or centralised into a Ministry of Planning. However, she recognised that, given the current political landscape and sectarian system, creating new institutions is extremely complicated and does not seem feasible in the coming years.

As stated by Harb, the urban expansion into Lebanon’s forested areas “is a larger situation of public policy making, which is focused on profit-making instead of people-centred and environmentally-centred policies.”

Illegal Logging

Illegal logging and woodcutting significantly impact Lebanon’s forests and are important drivers of deforestation, as noted by Joseph Bechara, a senior forest and wildfires management expert at the Lebanon Reforestation Initiative (LRI).

Joseph explained that organisations working in the forest protection sector witnessed a substantial rise in illegal logging and woodcutting in recent years, which is partly related to the worsening economic crisis Lebanon has been facing since 2019. Residents of natural areas often resort to logging to ease their financial burden by selling timber outside Lebanon or cutting wood for private use, including heating, as fuel prices have skyrocketed since 2019. Additionally, the insufficient number of official forest guards, and the subsequent lack of surveillance over natural resources, further compromise forest land protection in Lebanon.

Legal ways to prune – harvesting wood without killing the trees – should be encouraged, stated Joseph, offering alternatives to local residents and ways of benefiting from the forest they live in while preserving it. However, forest regulations rely on lengthy bureaucratic procedures, as permits need to be obtained from the Ministry of Agriculture. Forest activities, including pruning, coppicing, thinning and charcoal production, are, in fact, regulated by the forest code of 1949, which recognises four types of forests based on land ownership (private, municipal/villages, state, and state with usufruct rights for villages).

The long processing times for permits hinder their capacity to contribute to forest preservation, however, especially in the case of state-owned land, and several community leaders who spoke to The Alternative said this process should be streamlined. While more lax regulations could lead to local businesses exploiting forest land, solutions for expediting bureaucratic processes for individuals with good records should be in place to encourage good forest management practices among communities.

“We need a modern way of looking at and monitoring changes in land cover and use,” stated George Mitri, professor and director of the Land and Natural Resources Program at the Institute of the Environment at the University of Balamand. This would include creating incentives for privately owned landowners. As for state-owned land, the responsibility lies with the Ministry of Agriculture, which has initiated a process to update the 1949 law.

Wildfires in the Age of Climate Change

The United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), stated that the Mediterranean region is expected to experience a dramatic increase in mean temperatures, leading to increased extreme heat events. Such changes will be made worse by the concomitant decrease in average precipitation, and overall increase in aridity. All of these factors make Lebanon’s forests dangerously susceptible to severe wildfires.

Tani Hanna is the founder of the Tadbeer Organisation, a community initiative to prevent and manage forest fires in the village of Andaket in Akkar Governorate. He , notes that a large portion of Lebanon’s forest fires are started by humans – with more people attempting to clear land for income use since the country’s economic crisis began – but then spread out of control.

The Lebanese government has listed forest fires as one of the seven priorities of the Minister of Environment (MoE) and updated the national forest fire management strategy of 2009 (Decision No. 52/2009). The strategy clearly delineates the roles and responsibilities of relevant Ministries, the General Directorate of Civil Defence (GDCD), the army and security forces. The document stresses the importance of collaborating with local communities and to raise awareness and implement wildfire prevention and management protocol.

The ability of the ministry to act on this strategy is, however, dramatically compromised amid the government’s compromised fiscal situation and political deadlock, as Minister of the Environment Nasser Yassin recently acknowledged at a May 17 conference. The GDCD, the principal entity currently tasked with responding to forest fires in the country, is today operating at extremely limited capacity. A GDCD official who spoke to The Alternative said only 6 percent of its staff are paid – the rest being volunteers – and the organisation is facing a significant shortfall in ability to source equipment, supplies, fuel, spare parts, and mechanics to carry out repairs.

The GDCD’s inability to respond effectively to forest fires in 2019, 2020 and 2021 spurred various communities and grassroots actors to step in to try and fill the void. For instance, Hanna says the Tadbeer Organisation came together after a massive fire near the village of Qobayat, North Lebanon, in July 2021. In its aftermath, community members purchased equipment for a team of 30 people, built storage facilities, established a surveillance team, and have undertaken public awareness initiatives about forest fire risks.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), community-based fire management (CBFiM) is “a management approach based on the strategy to include local communities in the proper application of land-use fires wildfire prevention, and in preparedness and suppression of wildfires.” However, CBFiM guidelines warn against over-emphasising the role and capacity of local communities to fight fires, especially in contexts when government’s fire management approaches are hindered by access, response time and availability of funding as in Lebanon’s case. Defining and establishing the boundaries of the role of local communities is therefore a critical component and, in line with the FAO guidelines, “communities can only assist in large-scale fire suppression but should not be expected to shoulder the entire burden.”

Despite this, community groups are now the nation’s primary means to prevent and contain forest fires, according to Sammy Kayed, co-founder and managing director of the Environment Academy in Lebanon. He adds that this is untenable and that the burden of responsibility must be fairly distributed with the state, with local community groups playing a complementary rather than a primary role.

Looking Ahead

The country’s few remaining forests are a national treasure that should be preserved for the generations yet to come. As the experts consulted for this report have noted, with the right policy choices the drivers of deforestation in Lebanon can be reined in or, in the case of climate change, better prepared for to help curtail worst-case outcomes.

Recommendations

The pathway towards effective and sustainable urban and forestry management is paved with well-thought-out steps, beginning with the reinforcement of existing regulations. The “National Physical Master Plan for the Lebanese Territory” provides an essential guide, but its implementation needs strengthening. The establishment of a dedicated unit, tasked with overseeing urban planning matters, can help streamline processes. It also bolsters coordination among relevant actors, providing a focused approach to managing urban development.

To further harmonize the relationship between humans and nature, revisiting the forest code of 1949 is another step. Updating this legislation will offer more clarity on land tenure rights, helping to curtail damaging practices such as negligent use of fire to access land. In a bid to make this more appealing, incentives can be created for private landowners. This way, they’re encouraged to preserve forest areas, all while benefiting sustainably from them.

Yet, preservation efforts extend beyond just policy updates. Practical measures are also necessary, including outlining procedures to hasten the issuance of permits for forest management. Processes such as pruning and thinning, managed by the Ministry of Agriculture, should be expedited. However, this should only be after a careful review of the track records of individuals or entities submitting the requests.

Financing is another critical factor in forest management. Alternative routes should be explored to secure the financial resources necessary for the implementation of an updated national forest fire management strategy. Potential avenues may include international funding and strategic partnerships.

At the heart of these efforts should be a robust network of local stakeholders, bound together by a common goal: forest conservation. Strengthening stakeholder coordination and preparedness involves a consultative process, where the needs and capacities of community stakeholders are assessed. This evaluation, in turn, helps formally define the scope and means of local community engagement in fire prevention and management.

Preparedness also calls for planning for eventualities. Hence, implementing contingent recovery plans to rehabilitate fire-damaged areas becomes crucial. This effort should be coordinated closely with local communities, providing a sense of ownership and shared responsibility.

Lastly, ongoing engagement with non-governmental organizations and community-based organizations is essential to foster a culture of education-based awareness. These efforts help in preventing human-sparked wildfires, instilling a sense of respect for nature and the importance of conservation in our everyday lives. Through these integrated steps, we can work towards a sustainable future where urban development and forest preservation coexist harmoniously.