EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Lebanon’s worsening fuel shortage is not only bringing cars to a standstill; it is also reducing access to water for millions of Lebanese people. With the state only able to provide electricity for a few hours per day, and diesel for private generators increasingly scarce, water pumps across the country are grinding to a halt, causing shortages of this most basic necessity.

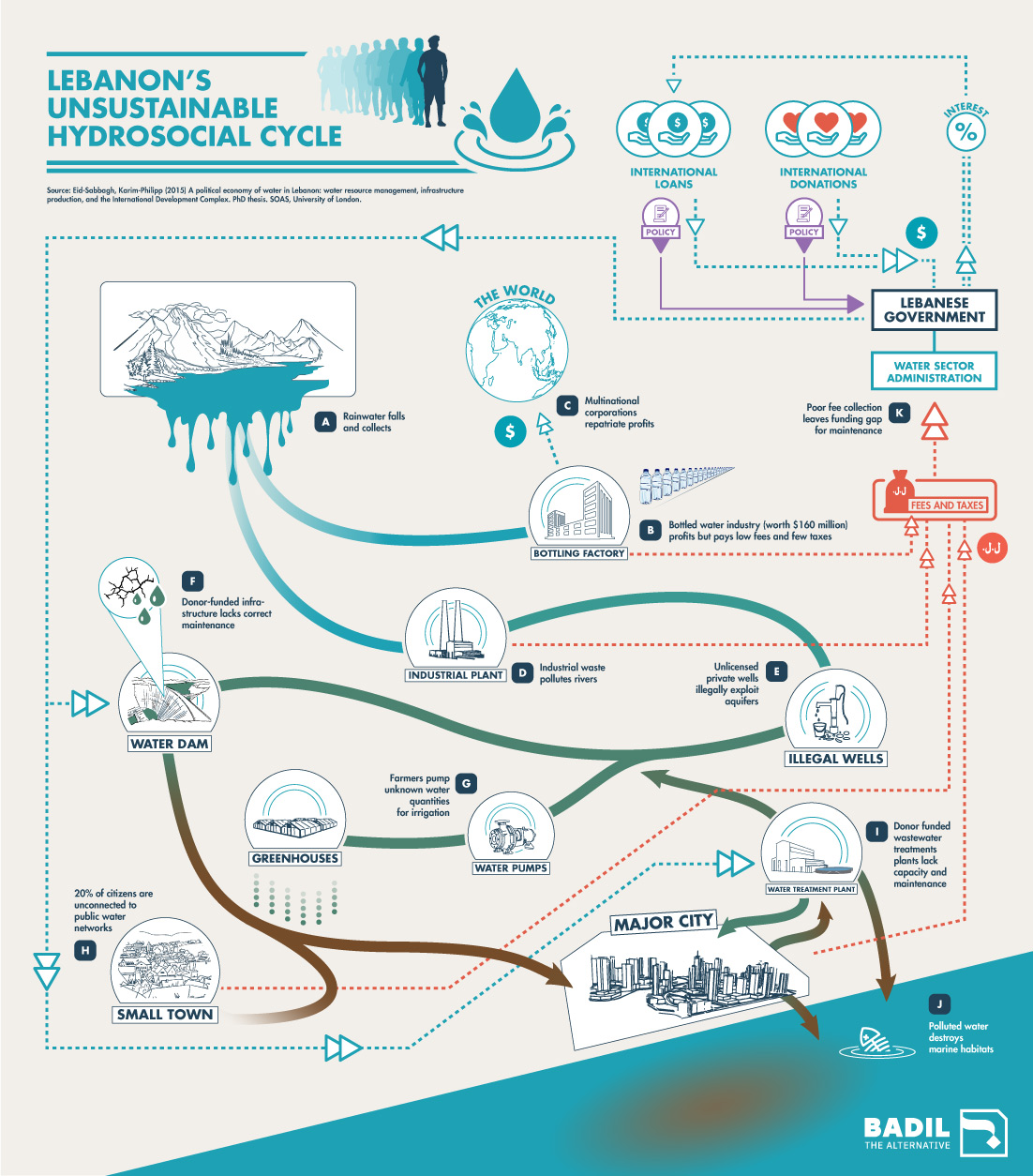

The ongoing economic crisis which lies at the heart of the current fuel shortages is exposing other frailties in Lebanon’s fundamentally flawed hydrosocial cycle – a term for society’s relationship with its water. Many can no longer pay their water bills. Those who can are paying in greatly devalued Lebanese Lira, an entirely inadequate revenue stream to maintain the already-faltering water administration bodies and their US dollar expenditures. While currency devaluation is a recent development, there are few signs of the Lebanese Lira returning to its old value in the immediate or medium-term future.

A corrupt and mismanaged state which deliberately promotes private interests above the benefit of the people brought about this dismal state of affairs. Since the 1990s, water sector reconstruction policies designed by donors imposing neoliberal conditions and a vested ruling elite have pushed the sector towards privatisation and debt reliance. Comprehensive mismanagement at all levels of water policy and administration has imposed extra cost burdens on Lebanese citizens in order to access basic water services through the private sector.

Like other aspects of Lebanon’s post-war development, the water sector was on dubious financial ground from the start. At its core, lay now-failed financial instruments, a reliance on US dollar loans, subsidies to fund activity, and mechanisms to reclaim costs in Lebanese Lira.

Even before 2019, outflows of US dollars in the forms of large-scale infrastructure projects, fuel and electricity costs, private sector profits and debt repayments were not matched by revenue inflows to state water providers in Lebanese Lira. While the illusion of future sustainability could be maintained when rising interest and debt secured the currency peg, the failure of market and private sector-oriented approaches to water provision is now glaringly obvious.

The collapse of the Lebanese Lira and US Dollar shortages now mean the entire system is at breaking point, from the fuel inputs to run essential services to citizens’ abilities to pay for public or private water.

The environment has been a major victim of this exploitative unregulated hydro-social cycle. Unmanaged waste dumping from households, agriculture and industry is leaching into groundwater, river systems and the sea, killing fish stocks and destroying ecosystems and valuable community resources. Heavy metals and carcinogenic pollutants dumped into the water system now enter the food chain and are found in soil and common vegetables.

Despite 30 years of disastrous water sector mismanagement, the latest master plan – published after the onset of the 2019 financial crisis – promotes the same failed prescriptions. Propping up Lebanon’s flawed water management system is guaranteed to end in disaster. Only people-oriented structural reform can bring about basic levels of social and environmental sustainability, achieving balance in Lebanon’s hydrosocial cycle.

THE COST OF FAILURE

For decades, citizens and the environment alike have paid the price for the Lebanese state’s widespread failings in the water sector. Although on paper a relatively high number of Lebanese households are connected to public water, distribution is deeply skewed, leaving many rural communities with little or no access for most of the year. Meanwhile, some half of the country’s water infrastructure is in desperate need of modernisation.1 Now, the consequences of a currency crisis – such as nationwide fuel shortages – are exacerbating an already fragile distribution and treatment network.

As is often the case in Lebanon, the price paid for the state’s deficiencies has always been unevenly and inequitably distributed. Poorer, geographically remote communities spend more on accessing water than richer, urban segments of society. According to one study, 25 percent of low-income households in Beirut spent more than a $100 a month on various sources of water in 2009 – the most recent report of its kind.2 Those who lack political connections and patronage networks also tend to pay more for water.

The sector’s failings are not only expensive for Lebanon’s citizens; they also cost the government millions of US dollars every year. A 2009 public expenditure review, the latest of its kind, estimated that water mismanagement cost the state 2.8 percent of GDP. 3 This expense is likely to be even greater today, as the economic crisis has hamstrung the most basic functioning of many state institutions. According to the latest available information, the state lost a further 1.3 percent of GDP from household spending on private-sector water, and 0.5 percent from hidden government costs.4

International loans and grants – which provide the vast majority of investment in the water sector – also represent extra hidden costs to the system. Even when given at concessional rates, most loans must eventually be repaid with interest. In the case of grants, funds provided to pay for foreign expertise or material are often repatriated in the form of foreign contractors and consultants, meaning that the money never enters Lebanon’s economy.

The environment also suffers from Lebanon’s aquatic inadequacies. Unchecked pollution is degrading water systems to the point where they cannot sustain life,5 and water-borne disease cases associated to bad water quality, have nearly doubled since 2005.6,7 Heavy metals and carcinogenic pollutants dumped into the water system – by industry agriculture, and illegal household dumping – enter the food chain and are found in soil and common vegetables.8 Wastewater provision is also substandard with a staggering 90 percent of sewage running untreated into watercourses and the sea.9 In greater Beirut alone over three hundred thousand cubic metres of untreated wastewater flows into coastal waters every day with disastrous effects on marine life and fish stocks.

Meanwhile, the country faces over-extraction which causes summer groundwater levels to recede and aquifers to be depleted, which in turn reduces well yields and increases pumping costs.10 Regional climate change exacerbates this pattern. River systems are so weak that they do not reach the sea for five to six months of the year. This increases pollutant concentration and threatens aquatic ecosystems when industrial and agricultural pollutants – which are also unregulated – discharge into the sea.11

Although quantifying the economic impact of these devastating practices is difficult, the World Bank estimates that environmental degradation from water pollution costs the country 1 percent of GDP every year.12 This cost, alongside multiple ruinous societal consequences, is especially dispiriting given that Lebanon boasts the fourth-highest water endowment in the MENA region.13 Unfortunately, the roots of this flawed and underperforming sector run deep. Now, Lebanon’s economic crisis is exposing these systemic failings which have their origins in the reconstruction period following the Lebanese civil war (1975-1990).

WATER OR WASTA?

Sectarian power jostling in the post-war reconstruction period set the scene for Lebanon’s water sector’s current disarray and broken hydrosocial cycle. Much like other service provisions, water management quickly fell prey to political patronage networks which dominated the reconstruction era; powerful figures benefit- ted from the sector by hiring personnel of their choosing and distributing contracts as they saw fit.14,15

Besides creating an inefficient and contradictory water administration system (See Box I), sectarian bickering also interrupted the legislative process, stalling crucial legislative reform. For example, the 2005 draft Water Code – which would have fundamentally overhauled the water sector – were blocked by disputes over the leadership of the High Council for Water.16 The law’s final iteration was ratified in 2018 under pressure to obtain some of the $11 billion promised through the CEDRE donor conference. Yet by 2020, no implementation decrees – the legal text organizing the practical implementation of laws – had been articulated.17

BOX I: Overstaffed and underperforming

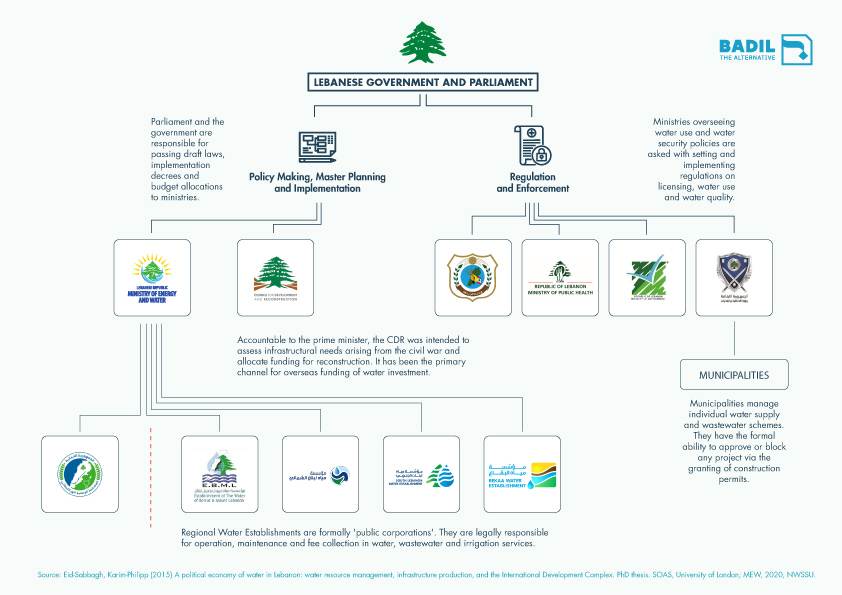

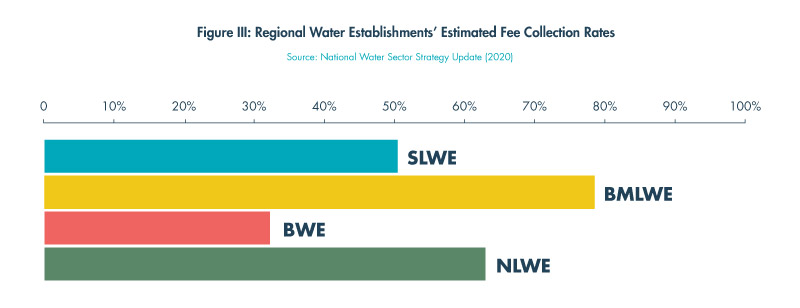

Lebanon’s water management system suffers from an over-complicated set of administrative arrangements across state agencies, public corporations, and private companies. Eleven state administrative bodies – excluding municipalities – hold overlapping responsibilities and compete over managing water resources, from producing infrastructure to operating services such as water supply, irrigation, and wastewater treatment. The main bodies are the Ministry of Energy and Water (MoEW), Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR), and four regional water establishments (RWEs) which are public corporations run by the MoEW. The RWEs are the Bekaa Water Establishment (BWE), Beirut Mount Lebanon Water Establishment (BMLWE), the North Lebanon Water Establishment (NLWE), the South Lebanon Water Establishment (SLWE). A fifth establishment, the Litani River Authority (LRA) is responsible for the management of the Litani River, specifically irrigation and power generation. Water use and demand is also shaped by broader sets of institutions, regulations and processes determining water and land use, import tariffs, and commodity prices.18They include the Ministry of Agriculture (MoA), Ministry of the Economy (MoE), Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) and Ministry of Environment (MoEn). Private actors are then heavily involved in construction and service contracting, and infrastructure management, bottling and trucking. Many of these bodies overlap. The CDR and the MoEW, for example, have similar responsibilities in planning and implementation. RWEs and municipalities also lack coordination; in fact, their relationship is often defined by competition over funds.19,20Water can be used as a bargaining chip in this incoherent and competitive administrative network (See Figure I).

Frequent interruptions of the legislative process also stymied government budgets, essential for planning and allocating specific sums to ministries. No such budgets were ratified between 2005 and October 2017 meaning that the Ministry of Energy and Water’s budget was not adjusted to meet changing needs for over a decade.21

In the absence of adequate finances and a strong, central water policy, and administration, the government looked to foreign funding to keep water in the taps. Since 1992, some $3 billion of foreign funding has entered the water sector. The World Bank, the European Investment Bank, Agence Française de Développement, the Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development, and the Saudi Fund for Development number among the largest donors.

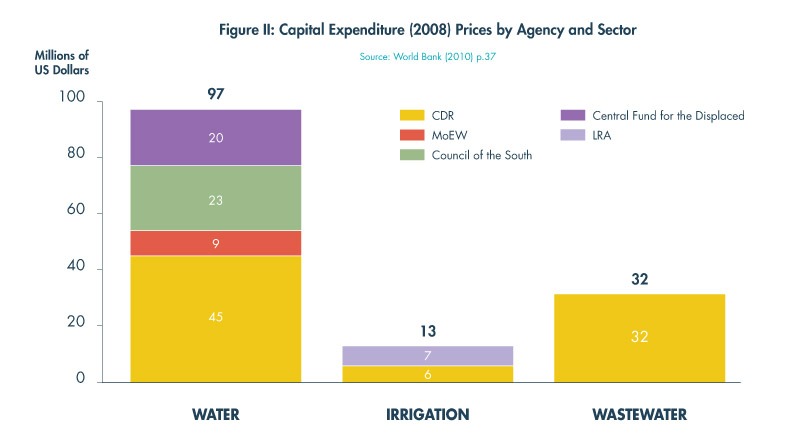

The main channel for receiving foreign funding is the Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR), a body responsible for reconstruction and associated contract negotiations with donors (See Figure II). Since ministries did not have engineering and technical capabilities, the CDR came to dominate project implementation too. Coupled with donor priorities, this dominance has emphasised large-scale projects and top-down planning in which grand visions overlook local water establishments’ capacities and local communities’ concerns.

MONEY DOWN THE DRAIN

Although foreign funding brought much-needed financing to water infrastructure projects, it did so at a price. Successive broadscale water plans and billions of US dollars in investment have failed to establish an equitable and efficient water system.

One major reason is that donors favoured large projects such as dams and centralised treatment facilities; by contrast, little attention was paid to the infrastructure connecting these eye-catching centrepieces. Irrigation networks, for example, are conspicuously lacking in do- nor-funded infrastructure projects. While approximately 60 percent of water is used for irrigation there has been general neglect of the agricultural sector, a key element of water policy. Since the civil war, the Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) has consistently received less than 0.5 percent of the government’s annual budget.22