OF BANKS & BILLIONAIRES

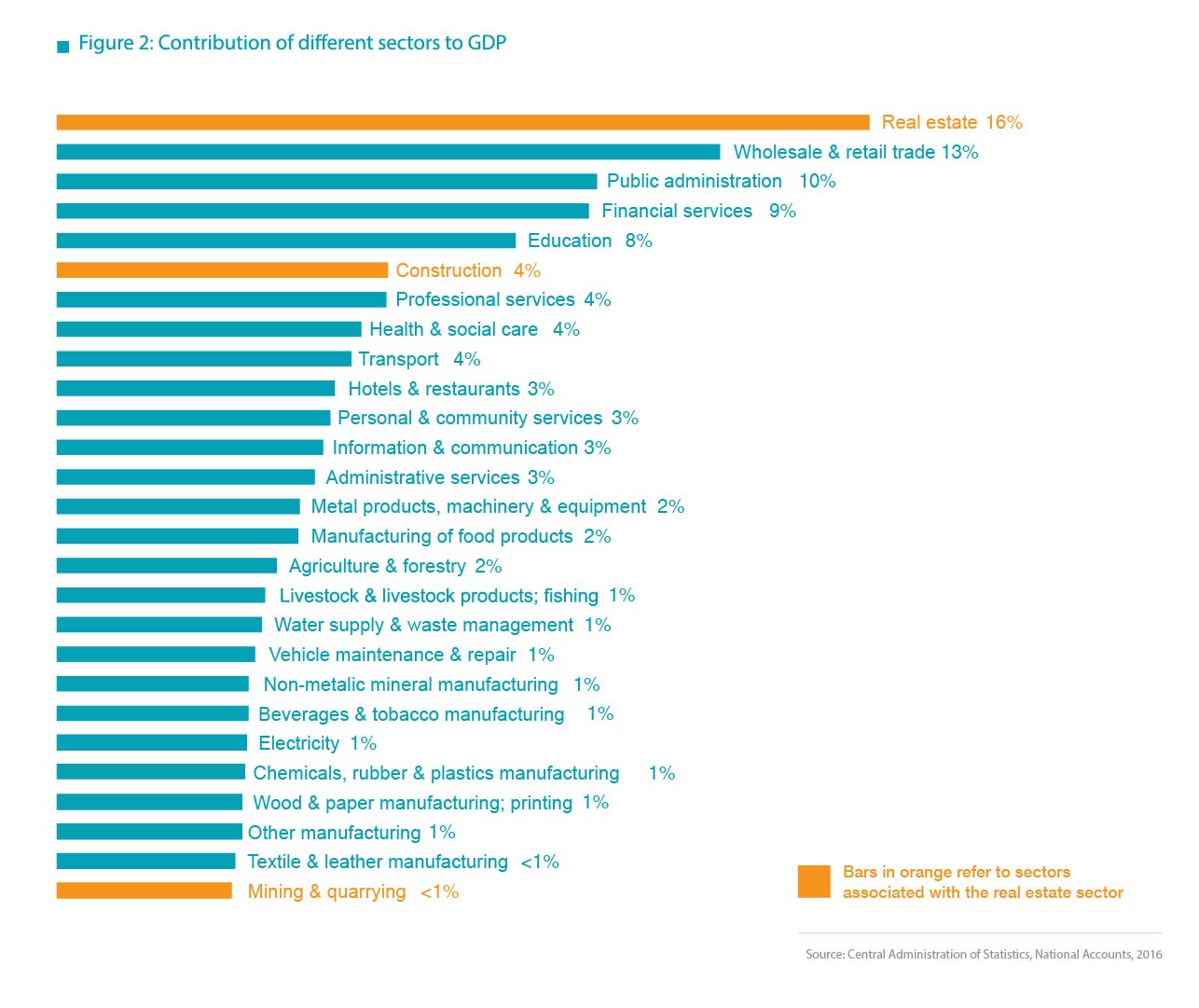

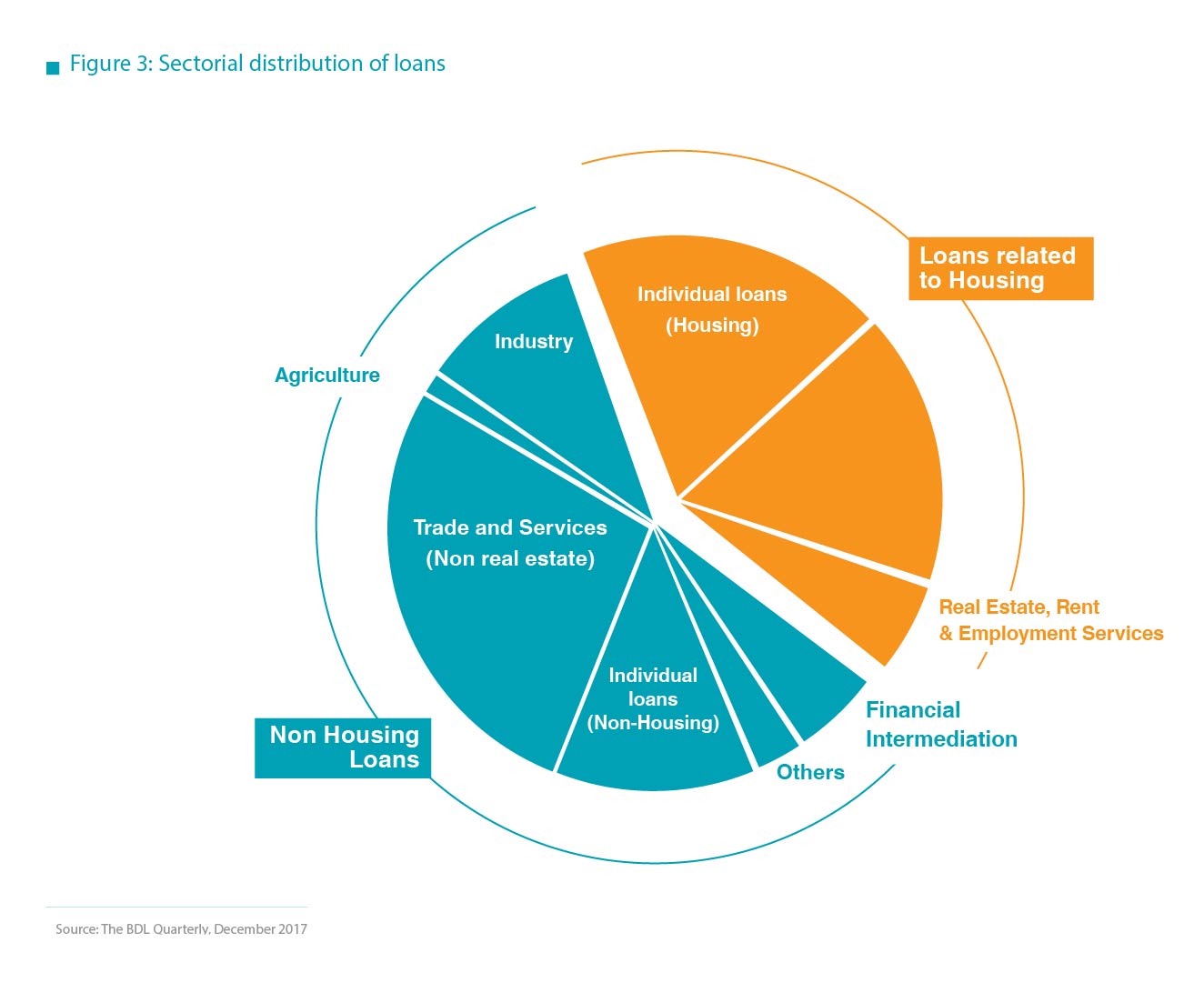

One could make the argument that support to the real estate sector is, in itself, a sound policy given that it is currently the largest sector of the economy—were it to falter so too would the rest of the economy. Indeed, that is the more plausible and understandable objective of the stimulus: the BDL is keen to support the loan portfolios and profitability of the banking sector due to the sector’s direct and indirect exposure to the real estate through housing loans and real estate collateral.

During the boom years from 2001 to 2011, three-fourths of the current real estate portfolios accrued, while housing and construction loans increased by 278% and 112% respectively.42 The banking sector is also indirectly exposed to real estate markets through collateral obligations and lending to developers, meaning 90% of all loans in the country are exposed to real estate in one form or another.43

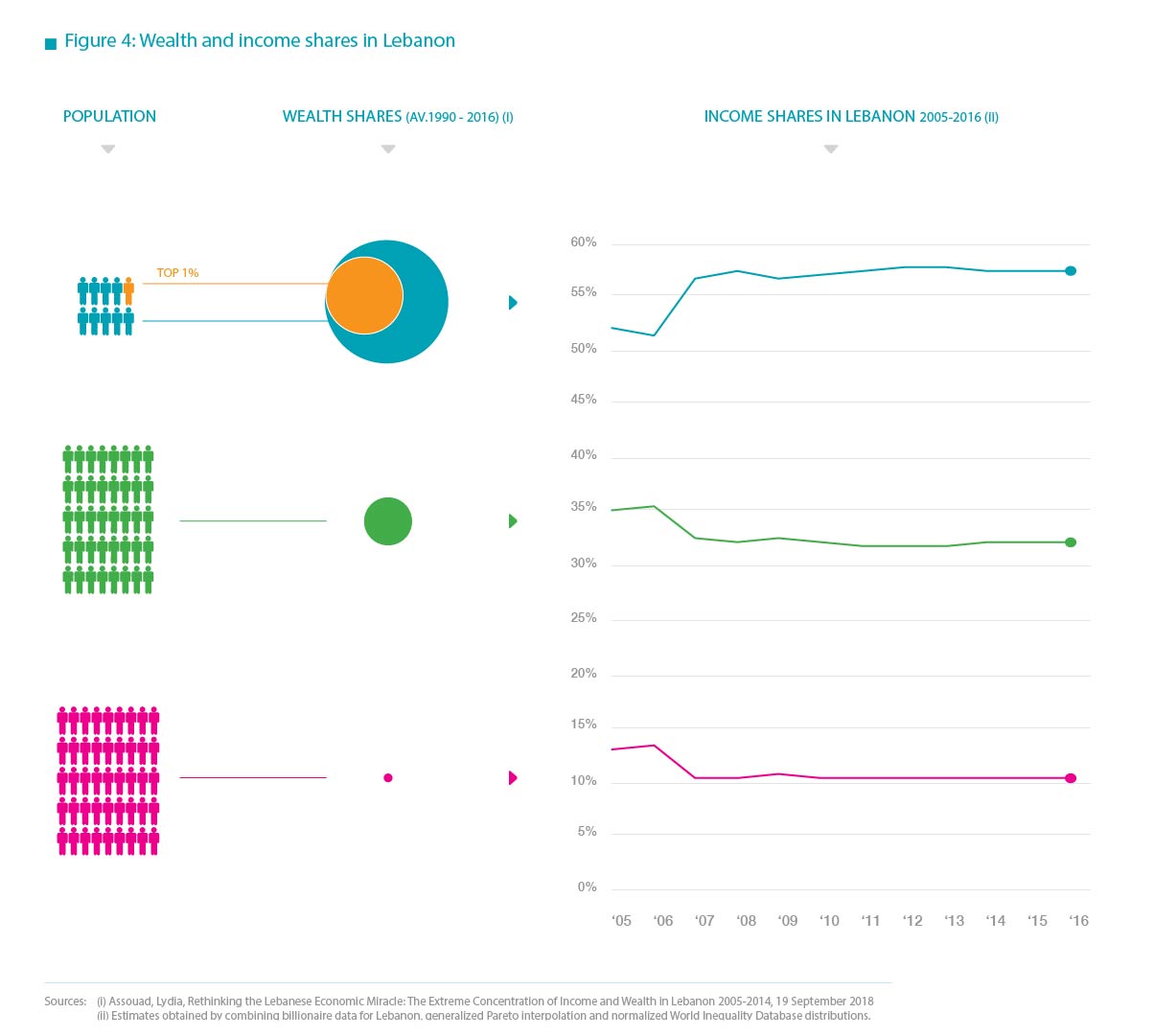

As this brief has shown, by supporting real estate prices, the BDL is not creating any significant number of jobs, but propping up unaffordable housing prices and fuelling inflation which slashes real wages. At the same time, the stimulus maintains artificial housing prices against market forces. And for the BDL, there seems to be no viable alternative to this vicious cycle until a serious reconsideration of the post-war relationship between the state and the banking sector materialises.

Since the end of the civil war, the banking sector has funded the state, sometimes at exorbitant interest rates of over 30%.44 The model of using debt instead of taxes to finance reconstruction was questioned at the time and, rather predictably, turned out to be a policy that contributed to Lebanon holding a debt-to-GDP ratio of some 160%, third behind Greece and Japan, which are of course already developed economies.

Yet unlike its Mediterranean cousin in Greece, the vast majority of the debt is held locally.45 Local ownership of public debt is often heralded as positive, given that it binds the holders to the fate of the country—but there is, of course, a catch. The BDL itself holds more of the public debt than any other entity. Indeed, Lebanon’s central bank holds 48% of local currency debt (USD 23.6 billion) in its vaults and, because it does not publish the amount, an unknown amount of foreign currency debt. The BDL does publish a vague statement about ‘claims on the public sector’, which do not necessarily represent the actual debt. Using a crude method of subtracting the central bank’s foreign currency holdings from its foreign assets, one can get an idea of the BDL’s debt in foreign currencies, which came to USD 20.6 billion in 2017. That brings the total proportion of public debt the BDL holds to some 55% (USD 44.2 billion), relative to some 40% held by commercial banks and 5% held by other financial institutions and debtors.46

In sum, the institution that manages the debt of the state holds the majority of that very same debt and, along with the commercial banks it offers subsidised loans to, makes a healthy profit off the interest charged: as of September 2018 one-year treasury bills (T-bills) in LBP yielded around 5.35%, while five-year T-bills yielded 6.47%.47 Interest rate payments to service the public debt make up around a third of the state’s total budget (around USD 5 billion/year),48 effectively impeding the state’s ability to fund public services, and leaving the Lebanese at the mercy of private service providers to cover everything from electricity, to water, to adequate healthcare.49

By the end of August 2018, public debt stood USD 84 billion, constituting an increase of 5.2% from USD 79.5 billion at the end of 2017. The continual ballooning of public debt–which has doubled over the past decade–requires a continuous injection of capital from remittances and deposits. Indeed, local and expatriate Lebanese are eager to invest their money in deposit accounts in LBP to benefit from slightly higher interest rates relative to the public debt (the average interest rate on deposits was 7.12% on LBP and 4.23% on USD in September 2018).50

But as commercial banks have to get their profit from somewhere, the stimulus provides a sure shot way for banks to have cheap access to credit, solid collateral from mortgages, and thus healthy and secure profits—the difference between what banks pay out to depositors is covered by what they receive from the government and from their largest portfolio, the real estate sector. Since 2011, there has continually been some USD 400 million in mortgages performing in the market.51 This has all translated into healthy profits for the banking sector. In 2017, Lebanon’s top banks52—which account for almost 90% of banking sector assets—made a total of USD 2.4 billion in profits and held assets of USD 233 billion, or some four times the size of the economy.53 As long as deposits flow in and there is confidence in the pound, the system works well: the BDL is able to offer subsidised loans in LBP, guarantee itself and the banks a healthy profit margin across their portfolios, the interest (never the principal) on public debt is paid, and everyone goes about their business. But it is never that simple in Lebanon.

When the current Prime Minister-designate Saad Hariri unexpectedly resigned from office in November 2017, there was a run on the pound. Some commercial banks started to offer interest rates on LBP deposits of up to 15% to keep LBP in the vaults.54

Perhaps, not by complete coincidence, this is also when the BDL, quite rightly, began to reconsider its stimulus policy. By continuing to artificially inflate housing prices, the BDL knows it is only prolonging the pain of an eventual correction that is already taking place in the housing market. Of course, there is pressure on the BDL not to withdraw its support, and it’s not hard to figure out where that pressure really comes from: 18 out of 20 major local banks have major shareholders linked to the political elites in Lebanon and 43% of banking assets in the sector can be attributed to political figures who either were or are currently in public office.55

CONCLUSION

TIME TO BALANCE THE BOOKS

Whether through subsidising real estate or raising interest rates, the BDL and the Government of Lebanon (GoL) are only prolonging the inevitable moment when the numbers won’t add up anymore. Yet fears that the LBP will devalue are likely to be unfounded: the central bank has USD 56.66 billion in foreign reserves to support the LBP,56 of which USD 11.36 billion (LBP 17.12 trillion) is gold bullion.57 But what is perhaps even more of a risk to the public good could be what is yet to come.

Now that real estate is no longer yielding as much profitability and inflation has reared its ugly head again, banks will almost undoubtedly demand higher rates to fund the government. The problem is that the government, which is connected to those same bankers, is fast becoming less able to justify a bourgeoning debt, and there are few options available.58

Already at the top of the list of possible fixes is privatisation of the few remaining public goods: telecoms, electricity, water and so on.59 The new public-private partnership (PPP) law is also being touted as possible fix for the problem, allowing banks to start funding public services and charging a fee for them. In tandem, there will almost certainly be calls to implement austerity in an economy which, as the past decade of austerity regimes in Europe have shown, results in economic malaise, a resurgence of (often ugly) populism, and weaker public services.

RECOMMENDATIONS

A NEW DEAL FOR LEBANON

While perhaps designed badly in Lebanon, in principle demand side quantitative easing in the form of stimulus has proven useful across the globe. Thus, instead of continuing to focus on bolstering the real estate sector, the BDL, the GoL and the commercial banks need to come together to enact a New Financial Deal for Lebanon. Conferences such as CEDRE can be beneficial, but will not resolve the vicious cycle of debt, artificial real estate prices and reliance on customer deposits.

Instead of allowing this to happen, then clamouring for the state to sell off its assets, a New Financial Deal will need to be based on a conditional haircut of the locally-held public debt. Given that the BDL is a public entity which holds more of the national debt than any other entity, it should be the one leading a drive to write down a large portion of the debt burden crippling the state and society.

The actual amount of debt relief can be calculated against savings in interest rate payments required to fund the much needed and called for reforms that the BDL, commercial banks and international organizations have been clamouring for decades about: civil service reform, infrastructure upgrades and social safety nets. In return the government must commit to a package of public sector reforms which spur economic growth in sectors that produce jobs for the Lebanese, growth for the economy, non-housing loan opportunities for the banking sector, and benefits for everyone—the citizenry, the banks and the state. At the same time, there will need to be a downward correction in the housing market and a policy focus on affordable housing. Then talk of a stimulus can recommence as part of the wider reform process (See Box 1).

Indeed, if just half of the USD5 billion in interest paid on the debt in 2017 were freed per year freed up, the USD 5 billon required to implement the five-year electricity sector reform programme could easily be allocated, and then some.60 Such moves will require genuine commitment from politicians and bankers, who are often one and the same person, to look beyond their own narrow interests. Yet the alternative is an eventual crash of the real estate sector, the national currency, deep economic depression and, inevitably, social upheaval—the consequences of which would be much worse than a little debt forgiveness.

| Box 1: Remodeled stimulus is key |

| For starters, the principle of any future stimulus should be to target job producing sectors first, and second to wean the real estate sector off cheap loans. As a reference guide, productive job-producing sectors (e.g. renewables, agri-food, industry) should eventually take up the lion’s share of stimulus packages, to the tune of 70% or more. The remaining 30% of the stimulus should then be used to supporting loans solely through the Banque de l’Habitat (BDH), the Public Housing Corporation (PHC) as well as towards construction for affordable housing. Managing this type of correction over the next couple of years, while keeping an eye on inflation, would allow banks to transition loan departments towards lending to more productive sectors and ensure that the correction in real estate prices is managed sustainably.

The ultimate aim of such a transition would be to support a national housing strategy, which seeks to provide affordable housing and reliable transport options to the population. There are a raft of incentive schemes that can be employed by the GoL to promote affordable housing, and even ways to fund such a move through long-awaited and required taxes on high-end properties, particularly unoccupied residences. Such measures would allow for inflation to be kept in check, as well as produce the type of local socioeconomic development required to reverse rampant urbanisation and concentration of economic activity in the capital. A real public housing initiative could even be need-based by employing a revamped version of the National Poverty Targeting Programme’s already available means testing platform.

For these reforms to be effective, the GoL and the BDL will need to be more transparent about the state of the housing market by first actually collecting and disseminating housing loan and price data. The dissemination of an index of house prices and a revamping of the real estate appraisals apparatus will be the first step in this process. That way, as this transition comes into place, the government and the BDL can actually have the tools to monitor and ensure that the majority, rather than the minority, of Lebanese can afford a home. |