Executive Summary

For years, blue-collar migrant workers have formed an essential backbone to Lebanon’s economy, working under the infamous kafala migration regime in positions considered undesirable by many Lebanese. Together, this largely male workforce attends Lebanon’s gas stations, cleans its streets, and stacks its supermarket shelves.[1]

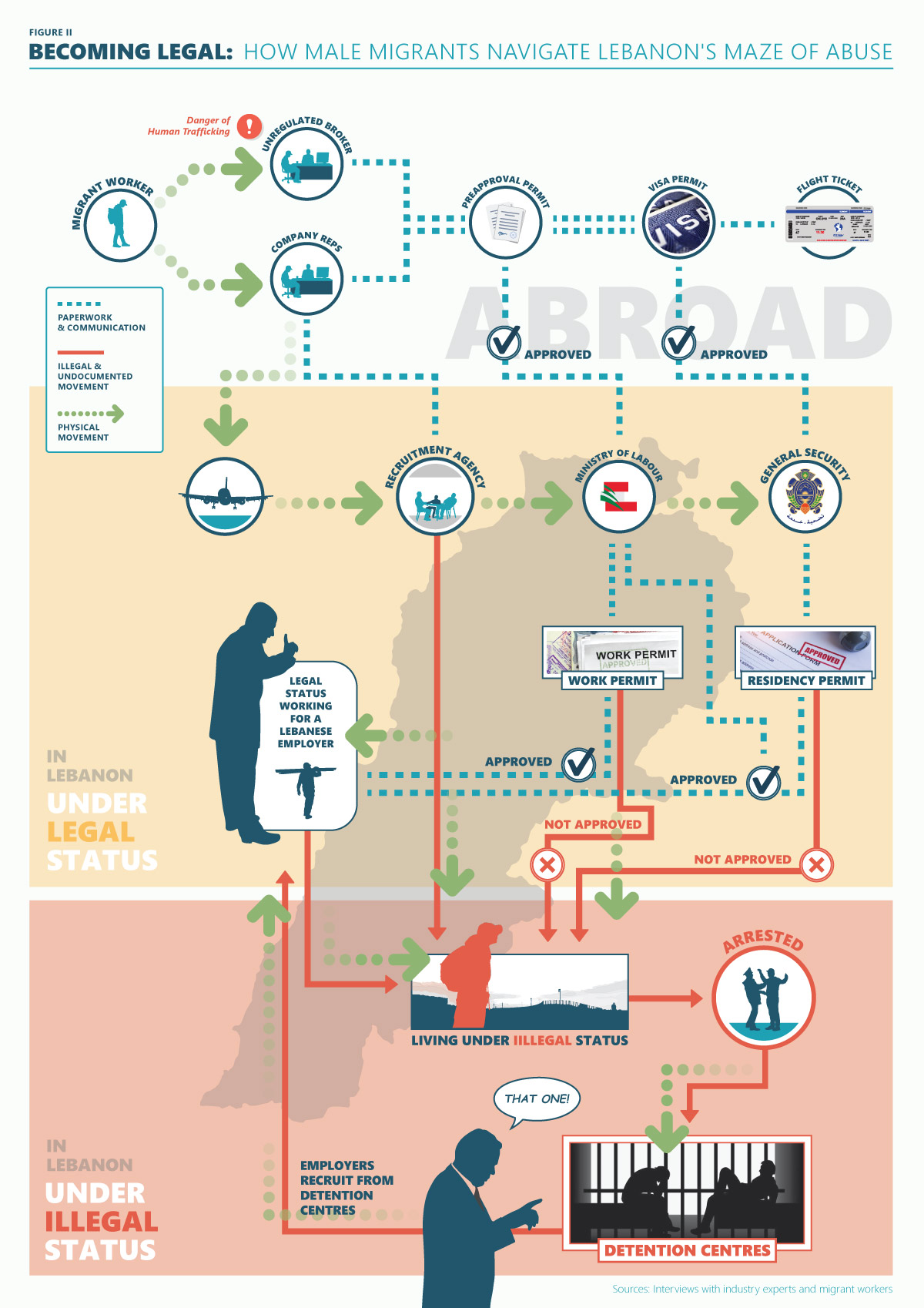

But the country which benefits from this plentiful source of cheap labour also systematically and cynically ensnares them in a web of abuse, opening the door to human trafficking networks. Lebanon’s Law Number 164 Punishment for the Crime of Trafficking in Persons in 2011 defines human trafficking as “luring, transporting, receiving, detaining, or finding shelter for a person… for the purpose of exploiting said other person or facilitating his exploitation by others.”[2] By its own definition, many of the thousands of migrant workers who arrive in Lebanon through unregulated networks are exposed to human trafficking.

When in Lebanon, those unfortunate enough to fall out of favour with their employer can quickly find themselves in one of the country’s squalid detention centres, such as the infamous dungeon under Beirut’s Adlieh junction. Often, illegal migrant workers have no choice but to accept another (potentially abusive) employer to correct their residency status and continue working in Lebanon.

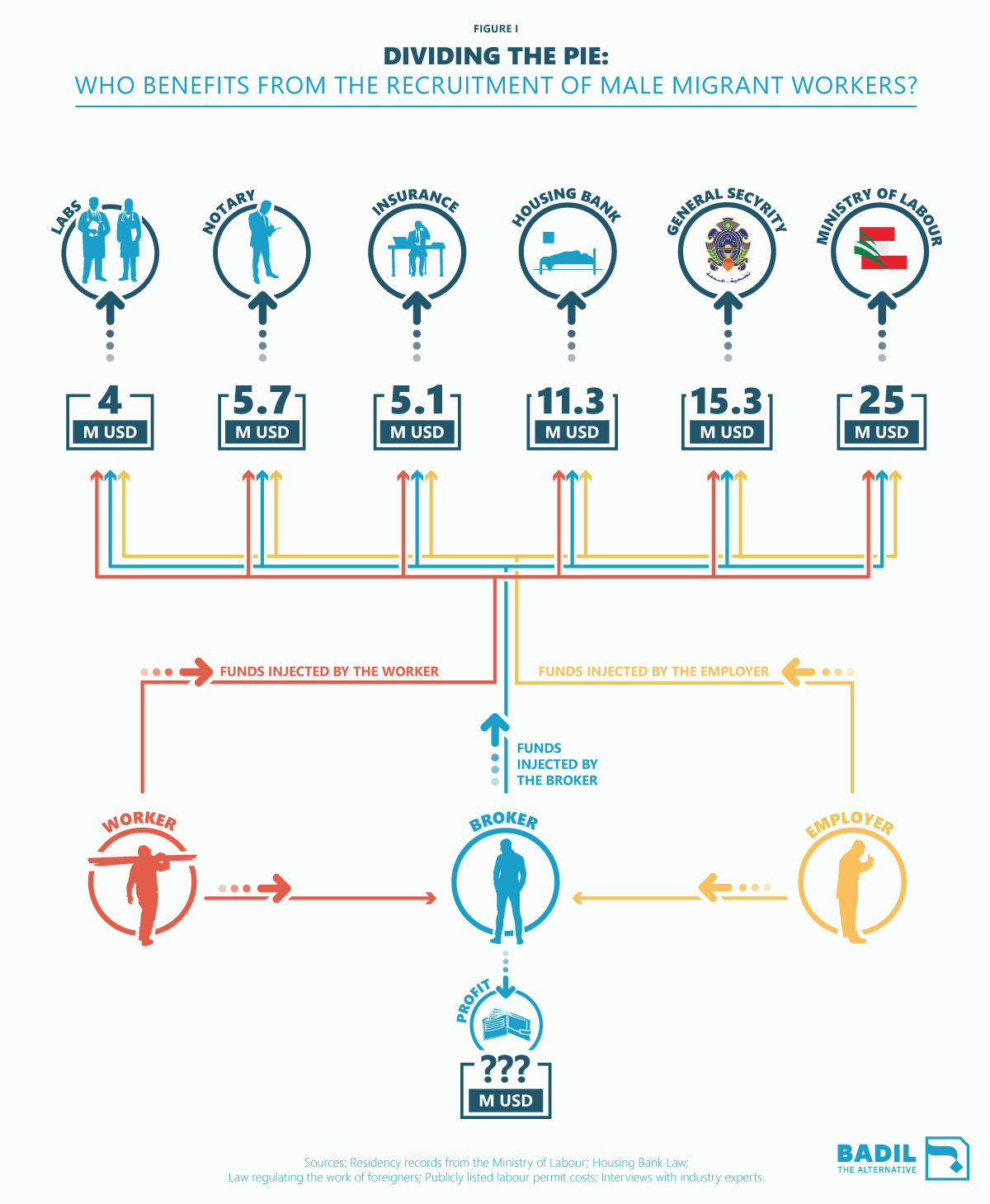

The decision to turn a blind eye to these disgraceful supply chains of blue-collar migrant workers is deliberate. Much like domestic workers (See: Cleaning Up, 2020), a lucrative value chain keeps this exploitative system afloat. Although smaller in numbers than domestic workers, male migrant workers in Lebanon generated around 60 million dollars a year before the economy crashed, according to Triangle’s estimates. This considerable pie is split by brokers and agents in foreign countries, the Ministry of Labour, General Security, public notaries, insurance companies, and medical laboratories.

Once they reach Lebanon, non-domestic migrant workers might expect the Labour Law to protect them from further exploitation. But here too, the state deliberately disappoints. While domestic workers toil outside the labour law, they at least enjoy a modicum of protection under a regulated migration regime. For non-domestic workers, poor enforcement, lack of social protection, and the threat of deportation or imprisonment without trial undermine non-domestic workers’ few legal entitlements.

Despite Lebanon’s economic crises, male migrant workers are still arriving in Lebanon on US dollar contracts. They will likely keep doing so, albeit in smaller numbers, until Lebanese citizens begin working in sectors traditionally allocated to migrants.[3] In the meantime, private companies, individuals, and public institutions will continue to profit handsomely from the continuing trade of cheap, exploitable labour.

The crippling economic crisis may provide a window of opportunity to reform a more just migration system. First, migrants deserve a proactive regulation regime to curb the unregulated and abusive recruitment sector. With new laws and meaningful enforcement, the Lebanese government could eventually deliver on its 2011 promise to stamp out human trafficking. More importantly, the state must ultimately scrap the kafala migration regime by delinking a migrant worker’s residency and work permits. Only by removing this outdated tradition will ensure that workers are treated fairly, and not as disposable indentured labour.

A Passage to Lebanon

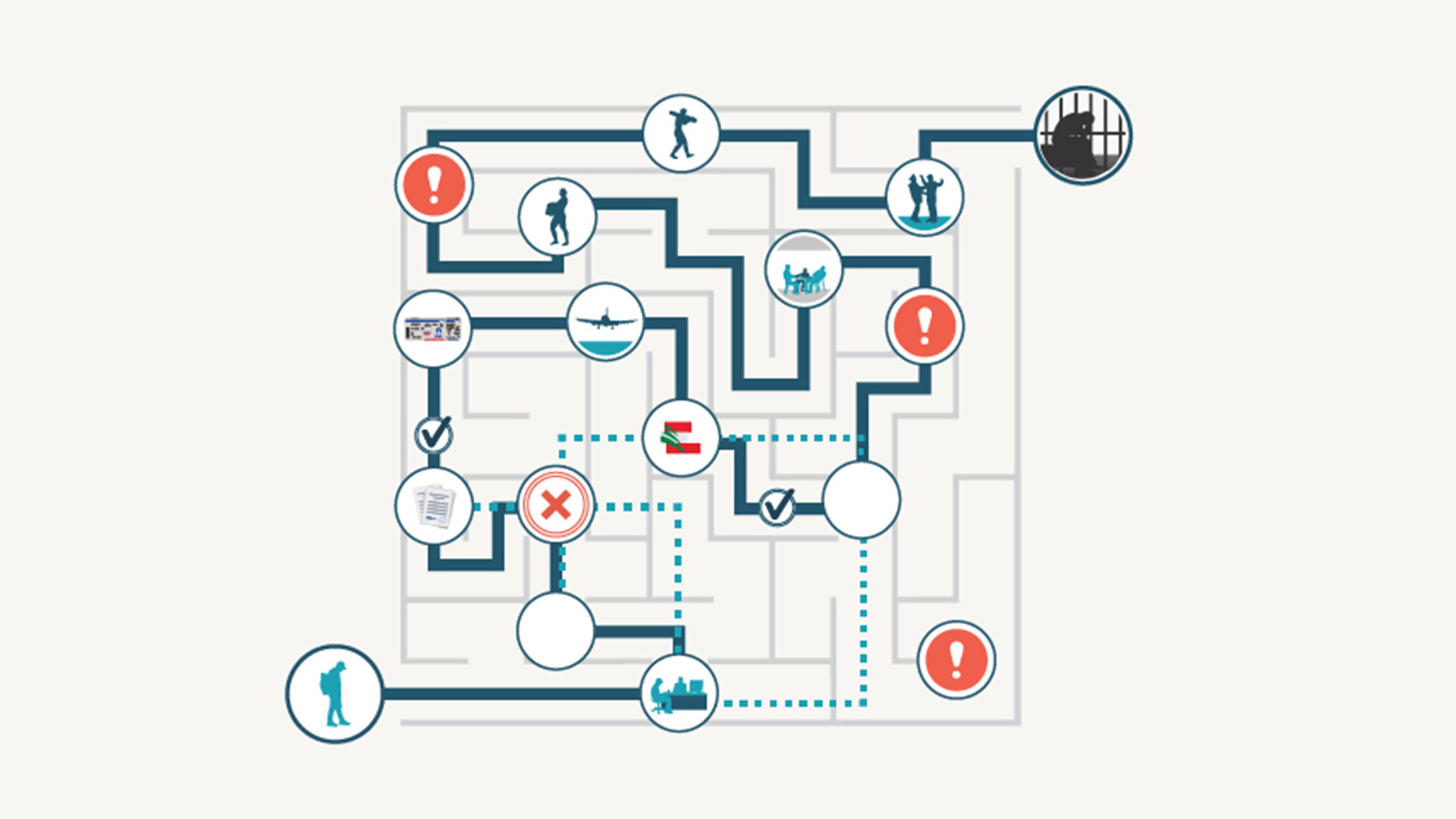

Male migrant workers face abuse and deception from the recruitment stage until they leave Lebanon. Even before arriving in the country, migrant worker hopefuls must take a considerable financial gamble; unlike domestic workers, whose passage to Lebanon is secured through a registered recruitment agency, non-domestic migrant workers must contend with a shady network of brokers. This totally unregulated network exposes migrants to abuse and human trafficking, as defined by the Lebanese law on human trafficking.[4]

The Tier System

Foreigners working in Lebanon are classified into four “tiers,” based on the worker’s profession and wage. The first tier is only for employers or self-employed who earn three times the minimum wage or above; this group of workers are permitted to bring their families to Lebanon. The second group are white collar technical workers whose salaries are between two and three times the minimum wage. Blue collars workers – including cleaners, porters, farmers, agricultural workers, gas station workers, and concierges – fall into tier three. The fourth and final tier is dedicated to domestic workers, who are usually women. The Lebanese Labour Law applies to all groups, except domestic and agricultural workers.[5]

A tier three worker (See Box I) has two main routes into Lebanon.[6] The first option is through an unlicensed recruiter or broker working on behalf of a Lebanese employer. A second more direct route exists through the employer’s own so-called “Human Resources” representatives working in the country of origin. For example, large construction and waste collection companies send their HR teams to countries of origin to hire workers directly.[7] In both cases, Lebanese law fails to provide any form of regulation or oversight of this abusive recruitment sector.[8] This legislative gap allows agents and brokers to demand arbitrary and unexpected costs with impunity.

The foreign applicant is typically promised a comfortable job with a well-paid salary starting at around 600 US dollars. In return, the recruiter demands that the foreign applicant or employer provide a valid passport and a broker’s fee in US dollars. The broker’s fee varies considerably between nationalities, depending on the proximity of the country of origin. This section assumes a conservative estimate of 4,000 dollars for distant countries and 500 dollars for countries with easier access to Lebanon.[9] Assuming that 11,325 new workers arrived in Lebanon in 2019, unregistered brokers took some 16.7 million dollars in application fees alone (See PDF Figure I).[10]

Some of this money is redistributed among various institutions and companies, covering the worker’s plane tickets to Lebanon, the cost of their visa, work contract, and pre-approval costs. The broker also takes a slice from this amount; while the exact profit margin is unknown, multiple sources agree that brokers are likely to reap several million dollars per year.[11] Indeed, the known cost of entry into Lebanon is a minute fraction of this amount. An entry visa, for example, costs 28 dollars, while an average aeroplane ticket from Bangladesh to Beirut costs around 325 dollars.[12]

The broker’s fee also covers other costs including a fee for obtaining a pre-approval permit from the Ministry of Labour[13] ($100),[14] a contract signed at a public notary ($100),[15] and a stamp ($0.80).[16] According to Article 3 of Law 17561 regulating the work of foreigners in Lebanon,[17] the foreign applicant can either apply for the pre-approval form from abroad or through an official representative in Lebanon.[18]