EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The first instalment of Triangle’s new working paper series ‘Who Will Foot the Bill?,’ examines the financial Ponzi scheme that brought Lebanon’s economy to brink of collapse. The paper also provides policy recommendations to build a more productive and sustainable Lebanese economic model.

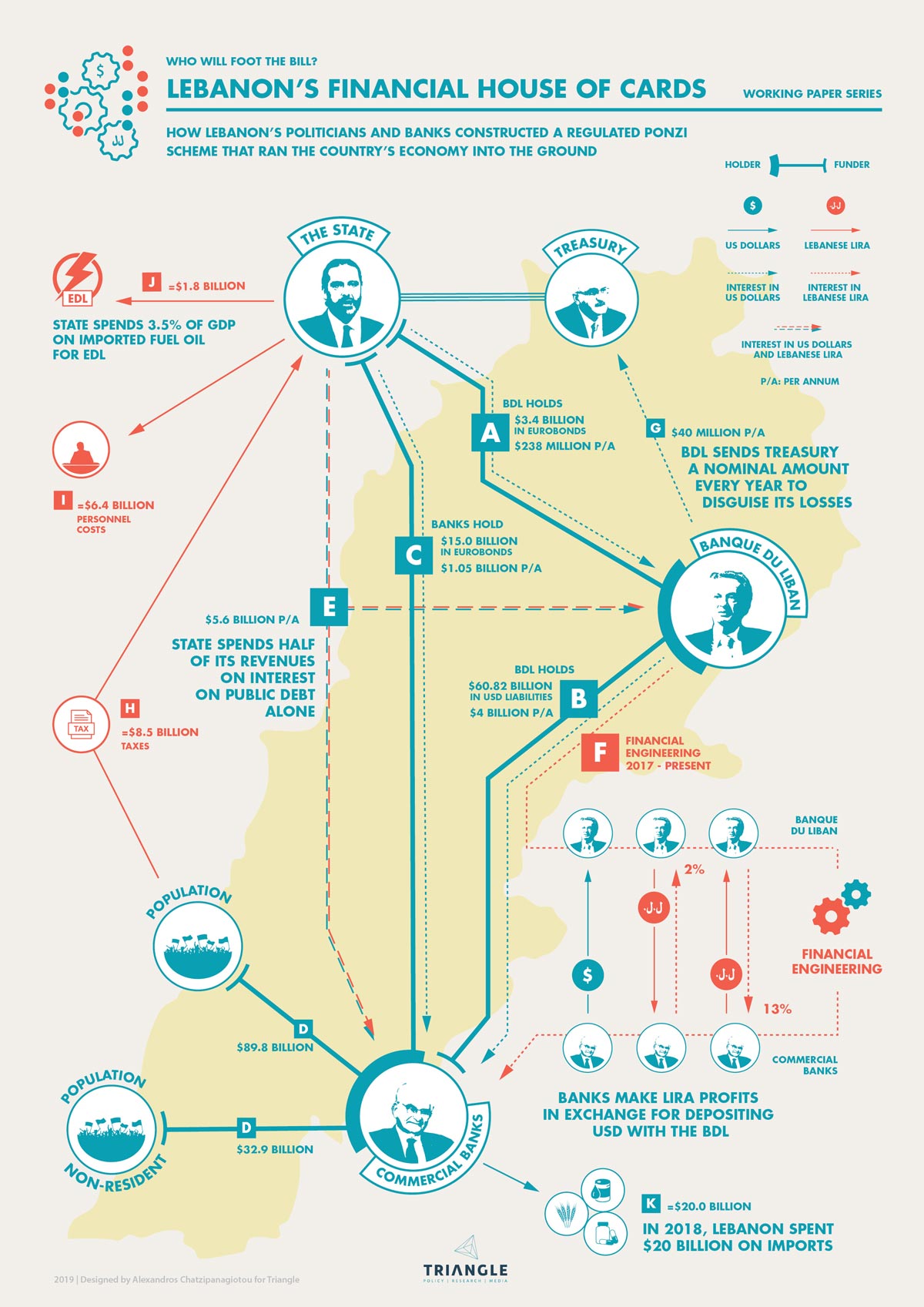

Since the end of its civil war in 1990, Lebanon has relied on banking, tourism, and real estate to attract foreign currency to the country, mostly in US dollars. For decades, those dollars have been recycled by Lebanon’s financial architects—the state, local commercial banks and Lebanon’s central bank, the Banque du Liban (BDL)—to create a regulated Ponzi scheme, which has benefited the banking sector and left the Lebanese people to foot the bill. Like any Ponzi scheme, Lebanon’s financial hustle relied on regular injections of US dollars to create a veneer of financial stability. This veneer masked a decrepit and untenable financial system designed to defend an outdated currency peg and increase banking sector profits. That is until now.

The monetary house of cards built and maintained by three financial protagonists—the state, commercial banks, and BDL—has come crashing down, precipitating a popular uprising alongside banking, currency, and debt crises. Without fresh foreign currency to fuel the Ponzi scheme, the BDL and the state are now unable to offer commercial banks extravagant incentives to park their dollars at the central bank.

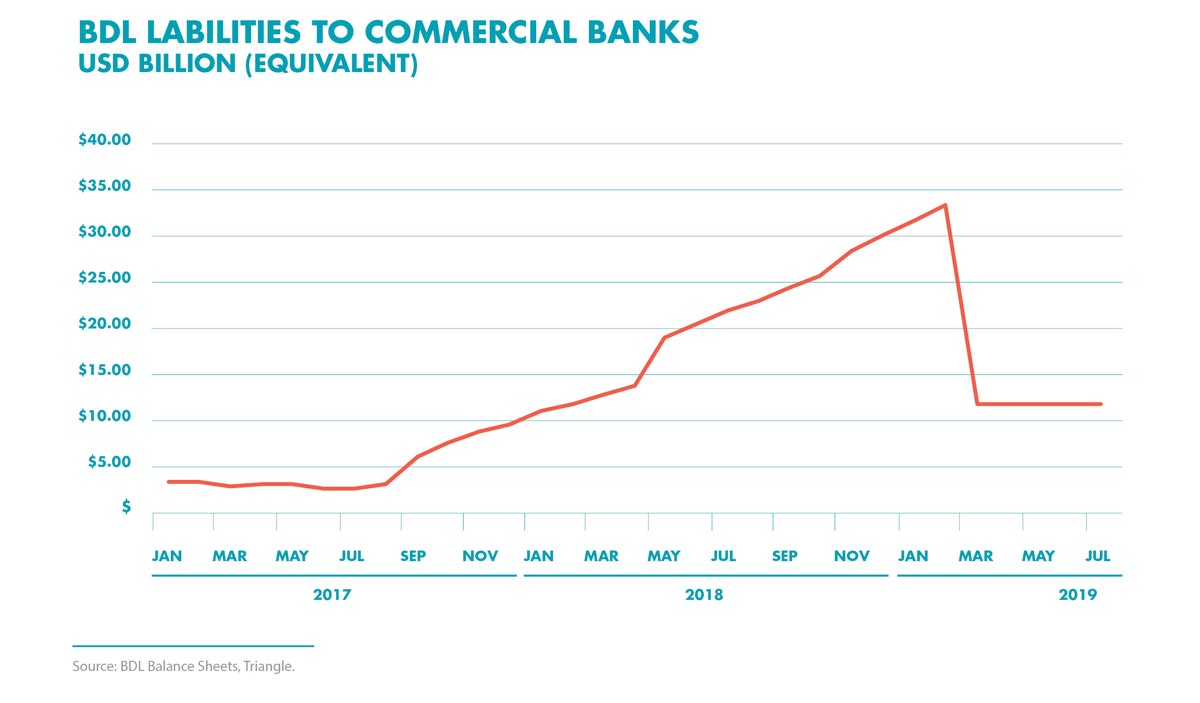

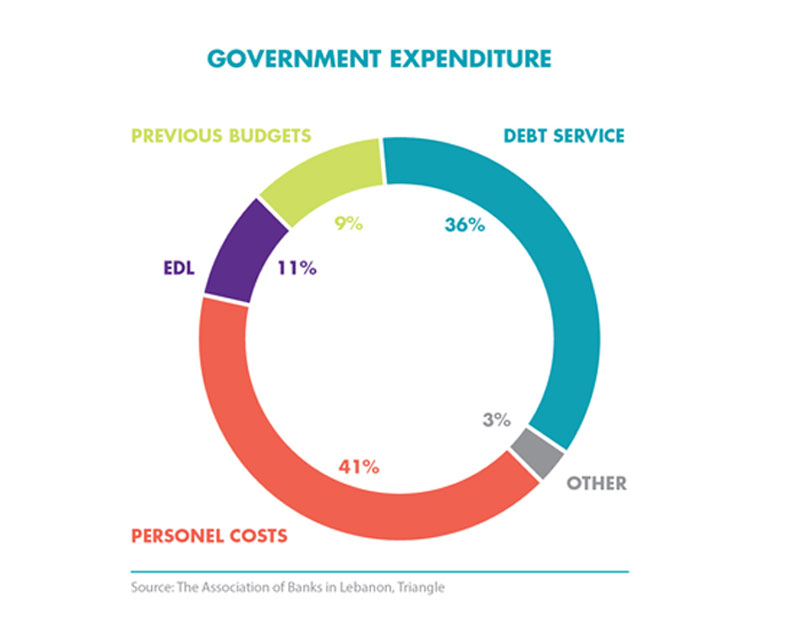

The BDL can no longer produce the estimated $4 billion annual interest it owes to the commercial banks on their $60 billion of deposits. As for the state, public coffers are unable to service the mushrooming public debt of some $86 billion, now third worst in the world relative to GDP. Economic growth is unlikely to solve the problem, given that Lebanon’s economy— worth a relatively meagre $55 billion in GDP—was

expected to contract by 0.2% in 2019. Alarmingly, that prediction was made well before the October 2019 uprising. Most analysts expect the coming recession in Lebanon to be severe; economies which experience debt, currency, and banking crises simultaneously contract by about 8% before they recover.

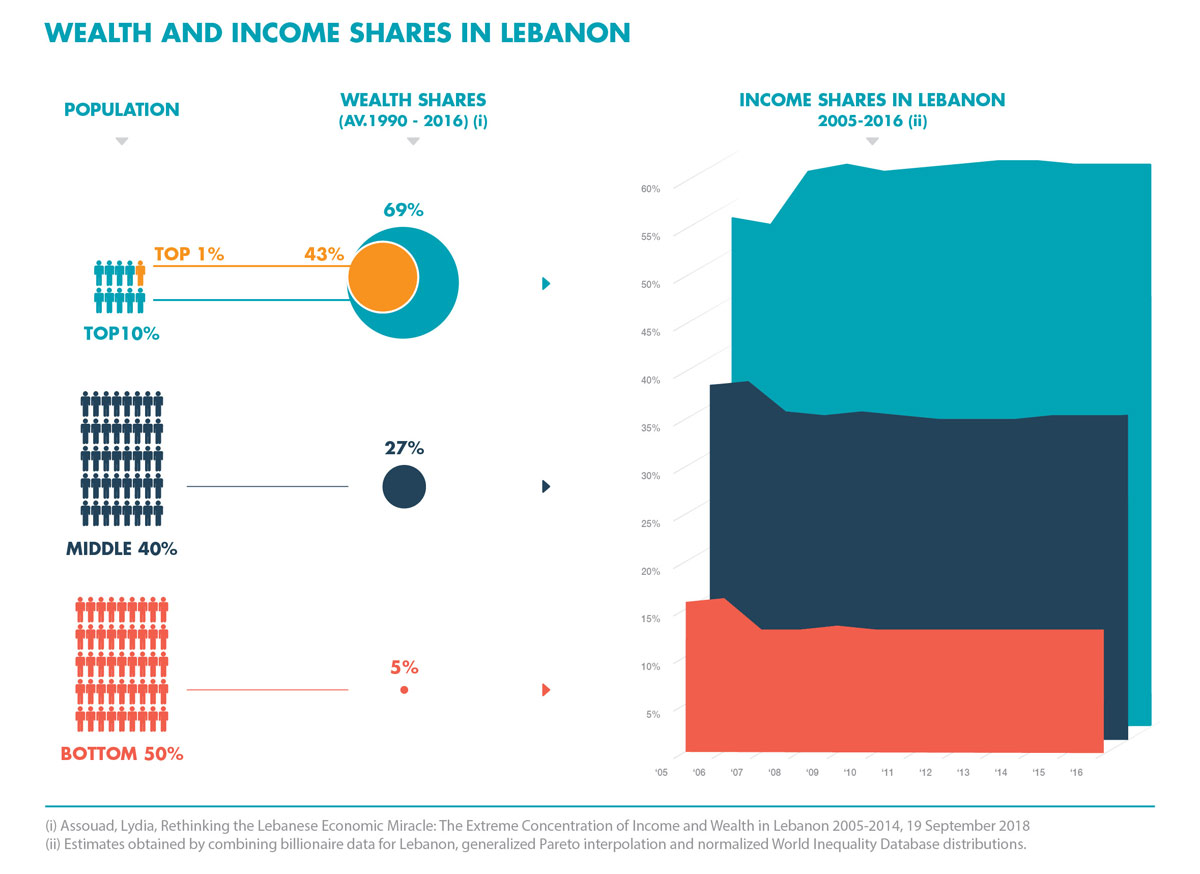

To stave off some of the pain, Lebanon will need to make some tough choices to regain the confidence of its people and the markets. For one, a progressive haircut is required. This mechanism, explained in greater depth in Box 3, would force those who benefited from Lebanon’s regulated Ponzi scheme to foot some of the bill. A partial and managed float of the Lira will also help reduce local currency debt obligations and bring back some logic to the exchange rate.

Longer term, a political transition away from narrow sectarian politics towards a civil state is the only solution which can viably produce the confidence, financial stimulus, international support, and political will to rebuild Lebanon’s decrepit infrastructure and capitalise on its few resources. These resources include human capital— one of the country’s few added-value exports—its geographic position as a transport and logistics hub, as well as a destination for green and sustainable tourism. Lebanon’s fledgling oil and gas sector will not yield dividends for several years. If and when it does, the state must be prepared to handle related contracts with transparency to avoid corruption.

After the October 2019 uprising, Lebanon’s economy will not be the same. Much will hinge on whether Lebanon’s ruling class is prepared to build a more rational economic model to ensure a just and productive future for the country. That future will need to focus on creating real value-added jobs through sustainable growth models. The alternative, which must be avoided at all costs, is a return to the artificial wealth creation that has already brought the country to the brink of financial, economic, and social collapse.

INTRODUCTION

In 1990, Lebanon laid in shambles. Fifteen years of civil war had decimated the country and its economy. A lack of confidence in the Lebanese Lira had created a dual currency system; to this day, both US dollars and Lebanese Lira are considered legal tender. But in the early to mid-1990s, the price of Lira to dollars was not pegged. The exchange rate fluctuated from around 500 Lira to 2500 Lira to the US dollar, wreaking havoc on the economy. In 1997, the BDL managed to stabilise the exchange rate at 1507.5- 1515 Lira to the dollar, creating a peg between the two currencies which has been defended ever since.1 To do so, then (and now) BDL governor Riad Salameh and successive governments embarked on a mission to attract foreign currency to the country. Eventually, the USD became the dominant currency in bank deposits, while the government tended to use Lira for meeting public spending needs, including the payment of taxes and of salaries of civil servants (See infographic: line H).2 Attracting enough foreign currency—from its diaspora or any other willing investor—became Lebanon’s modus operandi.

In order to maintain this system, a constant inflow of dollars was needed to cover interest payments on the public debt (issued by the state and the BDL), maintain the peg, and cover the need for imports vital goods such as fuel, medication, and wheat, which must be purchased in foreign currency. Aiming to secure this dollar inflow, the BDL and the state (through the Ministry of Finance) have historically offered interest rates well above international market rates to local banks in return for the banks’ investment in government debt. At the same time, the BDL also offers above-market interest rates to commercial banks and issues them with Certificates of Deposit (CDs).4

BOX 1: The BDL has denied that its interest rates on commercial bank deposits are “generous,” stating that rates “simply toe the country’s risk profile.” In other words, BDL argues that “money markets in Lebanon cannot trade at rates existing in AAA rated countries such as Germany or the US.” 4 However, in 2016 the International Monetary Fund (IMF) noted that the non-existence of secondary market trading, among other factors, means that “the LBP yield curve is determined by BDL,” warning that “the continuation of this policy will be adverse to the development of private fixed income securities.” 5

Under this system, interest rates on dollars and Lira are passed between these financial players to keep the system going; that is, until the supply of fresh dollars began to falter from around 2011. In 2016, the BDL started indirectly offering higher interest rates on dollars, a process which has become known as “financial engineering” (see chapter: Commercial Banks: The Risk Takers, Money Makers). While extending the lifespan of the dollar peg, these manoeuvres have been disastrous for Lebanon, causing inflation, a greater concentration of wealth, and decreasing Lebanon’s rating among international ratings agencies.6 Dollars started to be informally rationed in early September 2019 and by the time the popular uprising began on October 17, Lebanon’s economy was facing collapse.

To understand how Lebanon reached this point, this policy brief examines how the BDL, commercial banks and the state have been running a financial system that resembles a regulated Ponzi scheme which has run Lebanon’s economy into the ground. The accompanying infographic maps out the flawed system and can be followed according to letters marked A-J.

THE BDL: A FISTFUL OF DOLLARS

The BDL is by far the most important player in Lebanon’s financial system. Its mission, enshrined in the Code of Money and Credit, is to safeguard a sound Lebanese currency, economic stability, and the basic structure of the banking system, alongside developing the monetary, and financial market.7 Although the BDL is a public institution, it does not fall under the jurisdiction of any state body, except in so far as the finance ministry can look into the BDL’s accounting.8 The BDL can also issue debt in local currency, buy debt in both foreign and local currency, and issue CDs to creditors (mostly local commercial banks) to hold their money. As of March 2019, the BDL held over half of Lebanon’s local currency debt—$28.68 billion of the total $53.75 billion—and $3.4 billion in foreign currency debt, or Eurobonds [A].9

Yet the BDL does not publish key financial data which would allow the Lebanese public to understand the country’s financial position. This information includes BDL’s profits and losses, commercial banks’ USD deposits with the BDL, and, until recently, the interest which BDL pays commercial banks for deposits in dollars. Economists have estimated conservatively that between 2011 and 2016, BDL’s overall average interest rate to commercial banks on USD deposits was at least 5.5%.10 Others estimate that the average is closer to the Eurobond rate—the rate that the state pays creditors for foreign currency debt—which fluctuates between 7% and 8%. On November 11, Salameh announced that the BDL pays between 6.25% and 6.89% on commercial bank’s deposits with the BDL. Salameh alleged that this rate was well below the 15% global average. However, his claim should not be taken at face value since the global average interest rate on USD deposits is in fact considerably lower. The interest paid on dollars by the country that issues them, the United States, is between 1.5% and 2.4%.11

A copy of BDL’s internal unpublished balance sheets seen by Triangle reveals that, as of July 2019, BDL held the equivalent of $84.48 billion of commercial banks’ funds. These holdings existed in a number of forms: Lira and USD deposits, CDs and required reserves.12 Some of these funds bear no interest, while another part does bear interest. Since the BDL can print more Lira if it needs to, the most important liability for the central bank is the funds it holds in USD—or, in other words, USD-denominated CDs and required reserves in USD.