INTRODUCTION

This year – one of Lebanon’s darkest in recent memory – raised hopes for one promising legal reform: a small step towards dismantling the kafala system. For decades, Lebanese employers have exploited migrant workers under these draconian rules, which permit working conditions that are woefully paid, unsafe, and — in some cases — deadly. Under kafala, migrant workers are excluded from Lebanon’s labour laws and rely on their kafeel (sponsor) for residency. The rationale for this system is simple: it props up a financially lucrative industry.

In September, Labour Minister Lamia Yammine tabled a new contract that promised to improve the basic industrial rights available to migrant workers.1 The amendment proposed changes to the unified standard contract, which – if enforced strictly – would have allowed workers to receive the national minimum wage and quit without their employers’ consent, amongst other entitlements.2

Unfortunately, even these modest improvements drew resolute opposition. If passed, the new unified standard contract would deal a significant blow to commercial interests in the migrant worker value chain, which relies on providing cheap labour, free of basic industrial rights and obligations. Chief amongst these objectors was the Syndicate of Owners of Recruitment Agencies Lebanon (SORAL), which challenged the validity of the legislation in the Shura Council, Lebanon’s highest administrative court.

In October 2020, the appeal was granted.3 SORAL successfully argued that the new contract would negatively impact the industry of domestic workers recruitment in Lebanon, and contravene the labor law by giving domestic workers the national minimum wage.4 The Shura Council’s decision has consigned the updated unified standard contract to legislative purgatory, with no immediate prospect of becoming law.

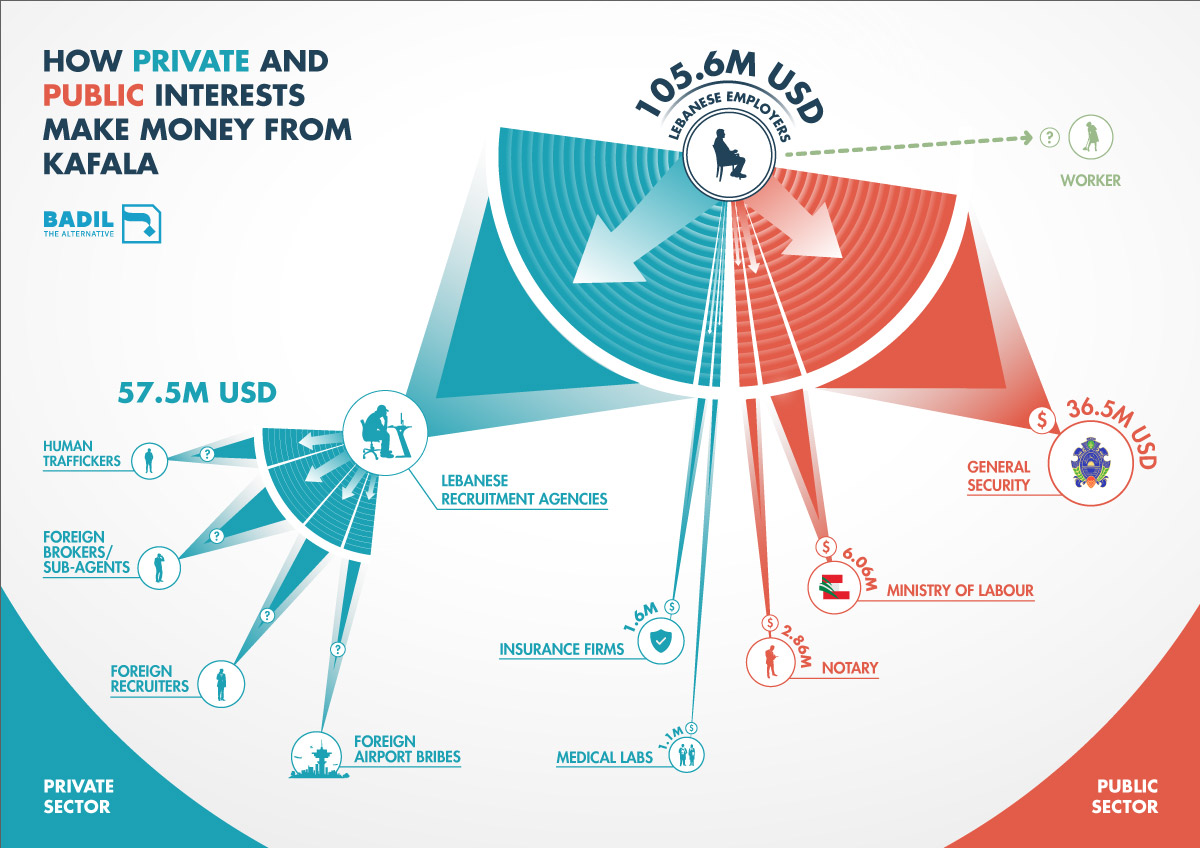

These recent events have underscored the pervasive lobbying clout of those who extract profits from the kafala system. For decades, a steady stream of domestic workers into Lebanon has provided a source of revenue and cheap labour for various Lebanese stakeholders. Recruitment agencies are the main direct financial beneficiary of this lucrative trade, receiving handsome yearly sums in the form of one-off recruitment fees. Meanwhile, Lebanese employers benefit indirectly in the form of cheap labour. Caught in the middle, and stripped of basic labour rights, domestic workers pay the price for this exploitative system.

The fight against the kafala system is far from over. Activists can expose kafala’s rapacious stakeholders by following the trail of dirty money, from human traffickers in the workers’ home countries to the Lebanese recruitment agencies themselves. Studies have already exposed parts of this avaricious trade in other countries; in Gulf Cooperation Council Countries, estimated yearly revenue raised for facilitating the entry and maintenance of Asian workers amounts to some US$4 billion.5 But, until now, Lebanon has lacked a comprehensive study on the economic interests which underpin kafala (see Box I: Lebanese Kafala: A Sensitive Topic).

BOX I: Lebanese Kafala: A Sensitive Topic

Lebanon’s sensitive political and demographic makeup poses specific challenges to reforming kafala, which do not exist elsewhere in the region. The Lebanese political system represents 18 religious sects to varying degrees, which can greatly hamper legislative reform in general. All decisions, from nationwide electoral laws to small-scale appointments of public officials, must preserve the delicate power sharing balance, creating regular political gridlock. Changes in the country’s labour laws, for example, must receive a nationwide consensus from various sects before they can become law, rather than requiring a majority’s vote in parliament.6 Since the country’s demographics also directly influence sectarian representation, further complications arise from deep-rooted collective fears of altering the country’s balance by “naturalizing” foreigners. As with refugees many Lebanese worry that granting more rights to migrant workers will be a precursor to extending citizenship, which could eventually alter the country’s demographic (and political) landscape.

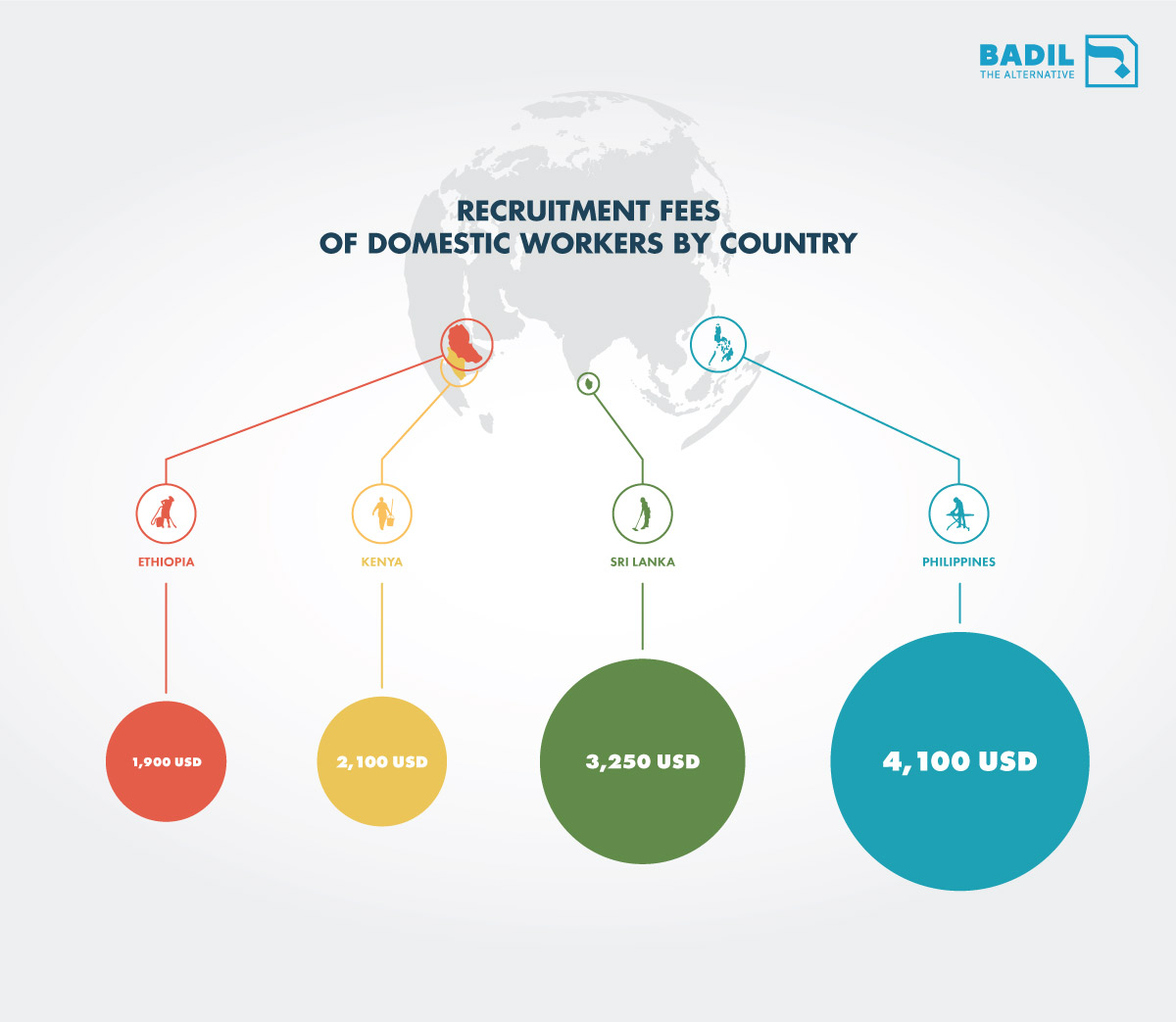

This report examines the financial interests served by Lebanese recruitment of foreign domestic workers, thousands of whom are hired every year from countries like Ethiopia, Sri Lanka, Kenya, and the Philippines. Armed with information about the economic interests in kafala, the Lebanese people can fully understand the weighty commercial interests that entrench this retrograde, immoral, and fundamentally embarrassing system.

THE RISE OF KAFALA CASH

Lebanon’s kafala system generates more than US$100 million in expenditure annually. A steady demand for cheap labour with virtually no rights keeps the cogs turning in this lucrative machine.7 The Lebanese Labour Law explicitly excludes domestic workers – both Lebanese and foreign – from its edicts.8 This glaring exclusion means that Lebanese employers save money by avoiding obligations owed under this legislation, such as paying the national minimum wage. Moreover, domestic workers do not have the legal right to act as, or even elect, union representatives.9 In 2014, when domestic workers (both local and foreign) purported to form their own industrial union, the Ministry of Labour refused to acknowledge the group’s existence.10

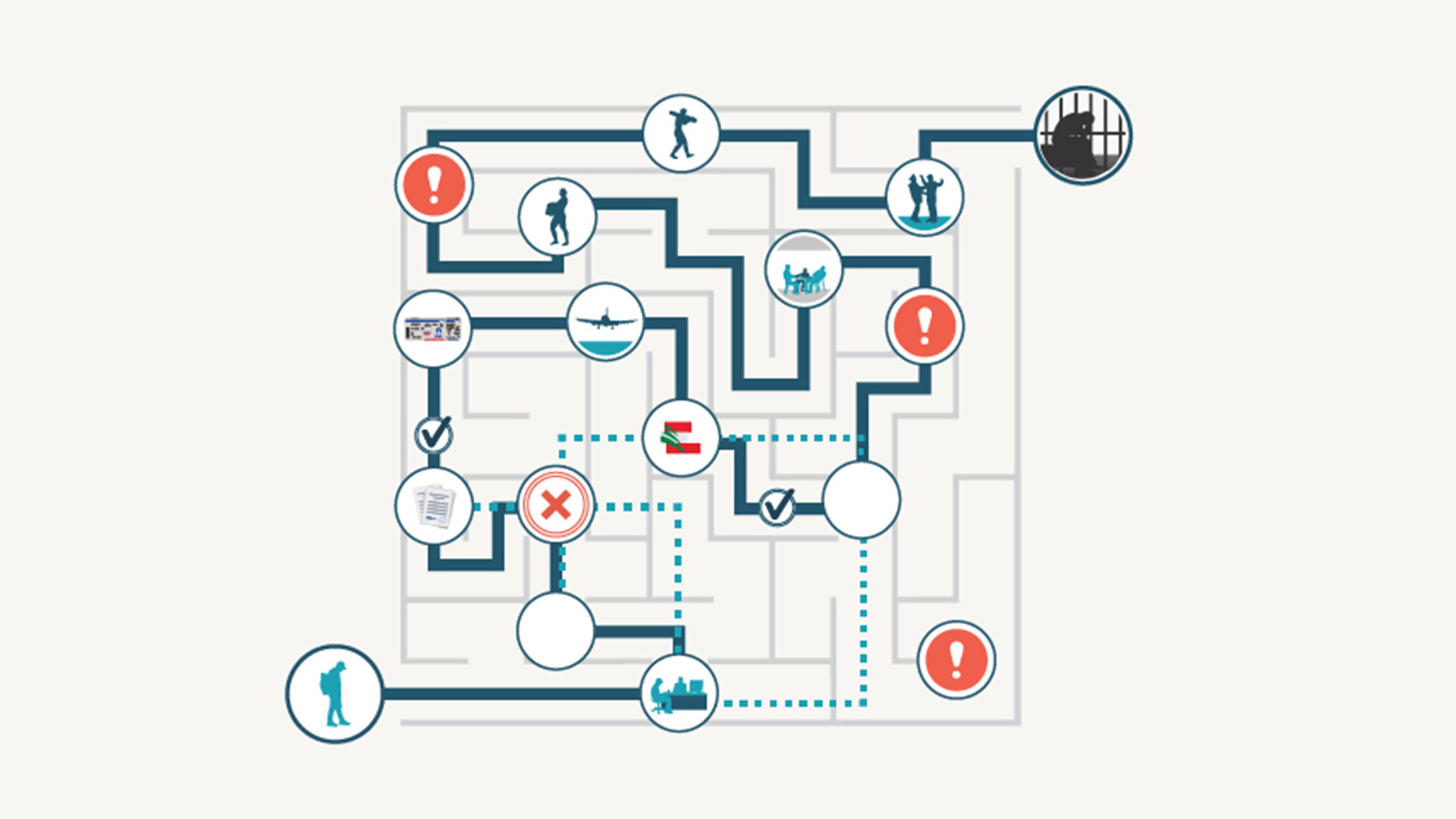

Instead, the workplace entitlements of foreign domestic workers are governed by the kafala system, a loose collection of laws, decrees, regulations, and customary practices. The central logic of kafala ties each worker to their kafeel (sponsor), who controls the worker’s legal status in Lebanon in exchange for wages, food, and board.11 Crucially, foreign domestic workers rely on their employment contracts with the kafeels for their continued residency status. Indeed, it is common practice for employers to withhold workers’ passports, even if the worker wants to leave their job.12 Thus, unlike Lebanese domestic workers, foreigners live under the looming threat of being cut adrift, and undocumented, if their relationship breaks down with the kafeel (see Box II: Hopes Dashed).

BOX II: Hopes Dashed

The recently defeated reforms proposed giving foreign domestic workers more rights under the unified standard contract, the source of these employees’ precious few legal protections in Lebanon. At least on paper, the current contract provides for basic entitlements like maximum 10-hour work days, one day off per week, and paid sick and annual leave.13 This year’s draft contract aimed at addressing the crucial issue of labour mobility. A procedural gap allowed the higher courts to postpone the contract’s implementation until the new cabinet can resolve the issue. At present, foreign domestic workers can only terminate their employment contract in very limited circumstances; the draft contract would have allowed them to quit at one month’s notice and find a new employer.14 The new contract would also entitled workers to receive the national minimum wage, less (unspecified) deductions for overheads like rent, food, and clothing.15

In practice, many foreign domestic workers do not even enjoy the limited rights under the current unified standard contract. Migrant domestic workers arriving in Lebanon are often confined to their employer’s house until the end of their agreement, which usually runs for 2 to 3 years, according to recruiters. During this period, employers wield expansive control over workers, whose communication is often monitored (or, in some cases, banned altogether). On top of this, workers have virtually no personal safety guarantees; activists have estimated that 1-2 migrant workers die every week.16 These abuses can occur with impunity courtesy of woeful state regulation, which frequently abandons foreign domestic workers to the whims of their kafeels.

While foreign domestic workers suffer deplorable conditions, their employers enjoy a dominant commercial hand. Under kafala, employers can demand that workers accept pitiful wages, put in overtime, and avoid making complaints – exactly because they are not subject to normal obligations imposed on employers. These circumstances make foreign domestic workers an especially cost-effective source of labour – one that typically works more, for less pay. Since domestic workers cannot expect minimum wage, their remuneration depends more on their nationality than individual skill or experience (See Box III: Racial Capitalism and kafala).

Box III: Racial Capitalism and Kafala

Racism is an inseparable part of the kafala system, which relies on recruiting non-native workers and subjecting them to lesser industrial rights than local employees. But Lebanon’s kafala system also discriminates between individual migrant workers according to their nationality, often completely overlooking individual qualities such as skill or individual experience. Therefore, kafala falls directly into the widely-accepted definition of racial capitalism as “the process of deriving social and economic value from the racial identity of another person.”17 In the Lebanese context, various costs including recruitment fees and monthly wages are dependent on a worker’s country of origin. In some cases, costs are influenced by ethnic stereotypes and prejudices based on the colour of the worker’s skin. Experts and recruiters interviewed for this paper informally describe this set of prejudices as a “colour scale.” This practice contradicts Lebanon’s legal obligations under various international conventions. These treaties include ILO Convention No.111 Concerning Discrimination in Respect to Employment and Occupation (which Lebanon has ratified) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Economic Rights (which Lebanon is party to).18