EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

With most Lebanese citizens cut off from their own bank accounts, economic rights in Lebanon are at an all-time low. Lebanon’s short-sighted economy has chased profits for the few at the expense of the general public, resulting in almost three quarters of wealth being owned by 10 percent of the population.1 Now, the general public stands to lose out on their pre-2019 savings to fund colossal sovereign debt created by the state’s economic mismanagement.

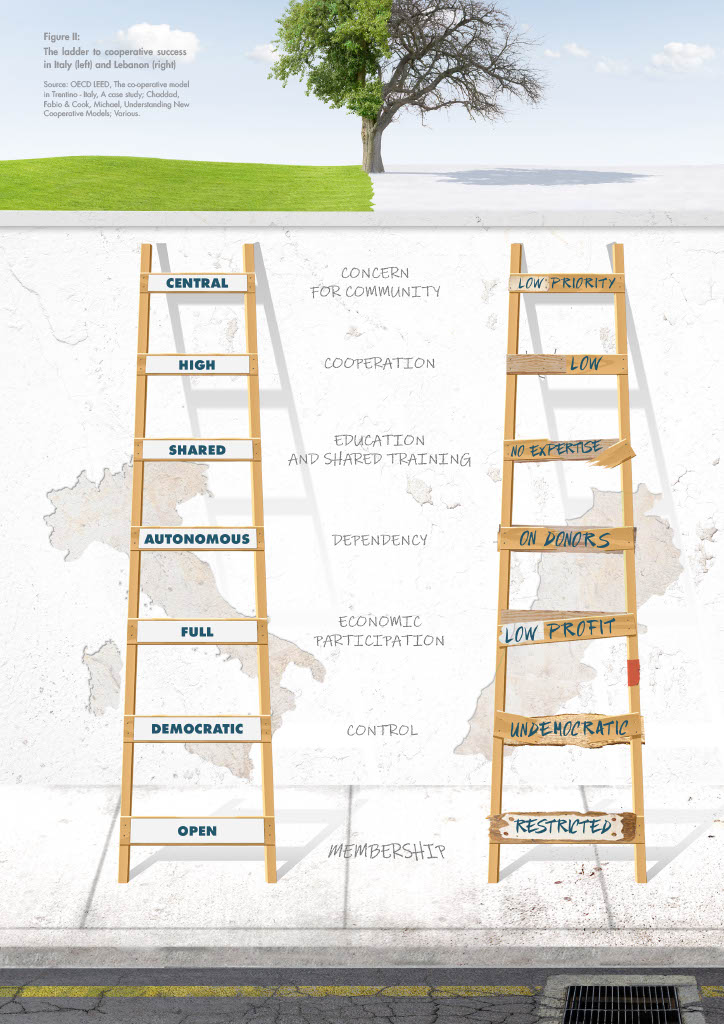

Funding from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) will now be vital to bolster Lebanon’s depleted current account and absorb some of the shock of devaluation. With it, Lebanon will be required to commit to a policy pathway designed to steer the country out of the crisis and restore trust in the country’s financial management. Faced with this bleak picture, it has never been more pressing to consider innovative working models to facilitate public participation in the economy and ensure equitable wealth creation and distribution for all. The fact that some of Lebanon’s existing cooperatives have managed to stay afloat against the odds represents a flagship model for facilitating economic access for the disempowered. However, today’s co-operative sector is stifled by poor legal frameworks, significant funding gaps, and cynical politicisation.

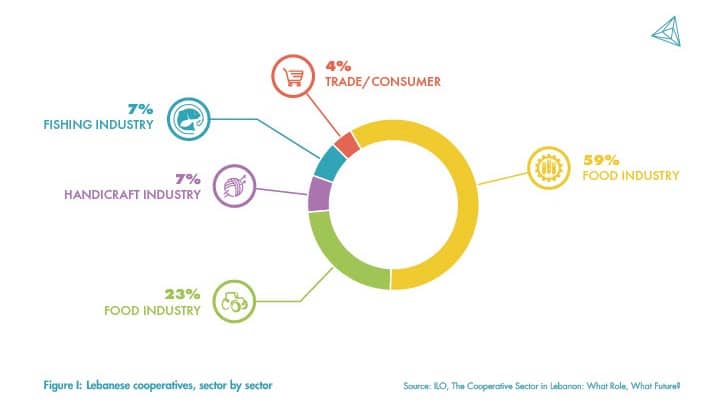

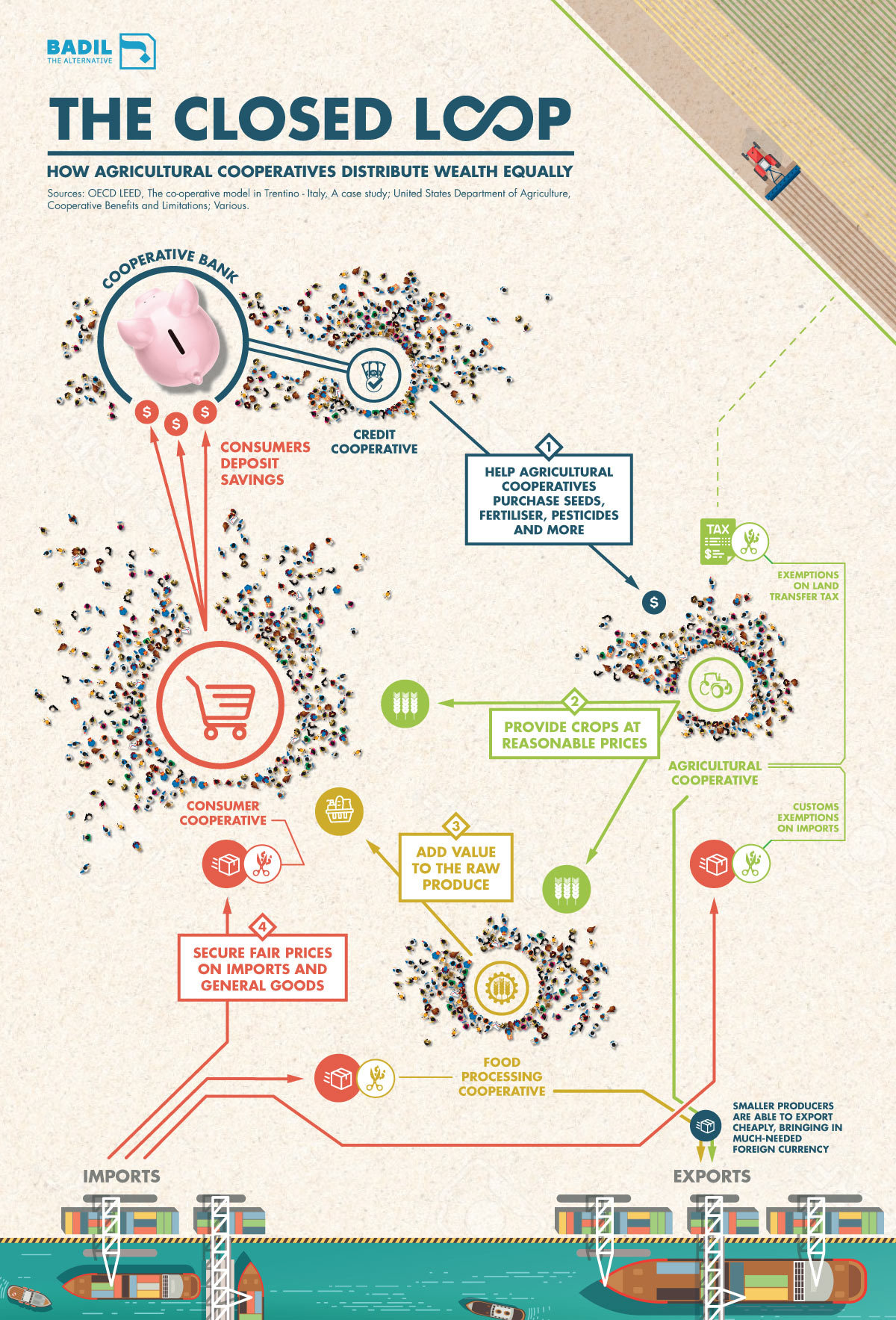

Existing cooperatives have achieved major gains for gender inclusion, for ensuring mutual profitability in an economy otherwise marked by extreme inequality, and for presenting a viable organizational structure to receive aid in dollars: a key stream of inflow during the crisis. While Lebanon’s cooperative law needs urgent reform, a vein of cooperative activity could still adapt to the needs of an increasingly industrialised and financialised global economy. This new cooperative model must focus on adding value through agro-processing, branding, and marketing, to tap into global markets and establish sustainable business. Lebanese exports could not come at a more opportune time, as producers are in dire need of fresh foreign currency.

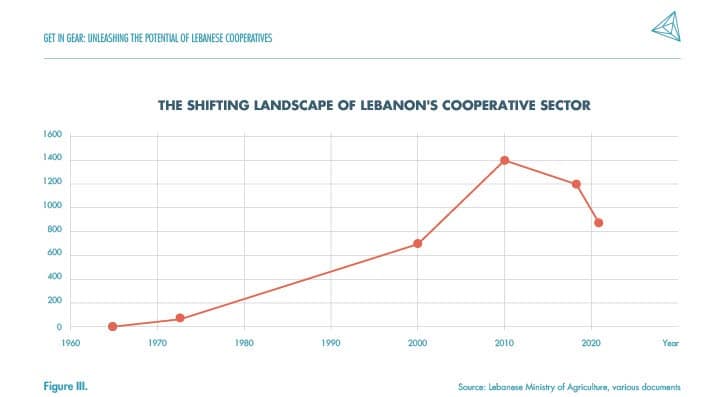

But without a dedicated policy approach, sustainable and non-partisan credit programmes, and mechanisms to ensure centralised regulatory oversight, Leb- anon’s existing cooperatives risk being drowned out by the corporate monopolies and oligopolies which dominate many markets. Changing this will require an effort of collective imagination to reverse historical trends. Cooperatives were first intended to counterbalance the industrialisation of agriculture in the 1960s, and later as a foil to the financialization of the real estate market: both policy attempts which did little to promote the genuine growth of an autonomous and organised bottom-up network. In the future, the state must invest more in the collective bargaining power of the cooperative model, which will promote an entry point into local, national, and even global markets for actors who would otherwise struggle to build sustainable businesses.

An astonishing 300 cooperatives were liquidated in 2020 due to inactivity, and those who are still operating currently depend on international emergency funding to keep operating. This shocking sign of stagnation is a product of systemic issues including outdated legal frameworks, under-resourced central management, politicisation, and a lack of financing for producers. Given these shortcomings, Lebanon’s cooperatives currently rest on a crutch of donor funding – a support which may disappear as quickly as it arrived.

FRAMEWORK FOR FAILURE

The current legal framework for cooperatives dates from 1964 and does little to support existing cooperatives to operate in competitive markets. While to- day’s cooperatives enjoy certain benefits including exemptions on income tax, land tax, various forms of stamp tax, the legal framework falls short of promoting a flourishing cooperative sector (See Better Together). Legal failings can be attributed in large part to the shaky foundations upon which cooperatives were founded, in addition to the rollback of social reforms during the civil war period (1975-1990) and in the post-war period. Due to this neglect, legal frameworks remain outdated and ill-equipped to support modern cooperatives.

Lebanon’s law on cooperatives was first ushered in during the Chehab era (1958-1970), a period which saw a short-lived political appetite for nationalizing the economy and for social reform. Cooperatives, then placed under the care of the Cooperation Department at the Agriculture Ministry, were just one of several reformist tools deployed by the Chehab government to try and reshape Lebanon’s economy in favour of empowering economic participation at the local level. The 1964 Law on Cooperative Associations served to stimulate the burgeoning cooperative sector by establishing the National Federation for Cooperatives as the sector’s official union and the National Union for Cooperative Credit as its specialised lending body.2 During this period, cooperatives were established with remits as diverse as “promoting poetic and philosophical education” to more traditional co-operative activity such as housing, beekeeping, olive and fruit farming and agro-processing and consumer and credit cooperatives.

Better Together

Cooperatives are entitled to a list of exemptions and waivers, including exemptions on income tax, land tax, various forms of stamp tax.3 Co- operatives have the right to receive grants and bequests, and the General Directorate of Co- operatives is supposed to appoint an auditor to conduct an annual review of the cooperative’s accounts and management.4 Specifications pro- vide for the redistribution of any surplus,5 prohib- iting the charging of interest beyond that need- ed to maintain the share’s value, and to prevent one member holding over a fifth of the shares in any given cooperative. However, cooperatives are also bound by strict rules which limit their growth; for example, only one cooperative for any given purpose is permitted to operate in a village, unless there are over 20,000 residents. A minimum of 10 members should be registered at the time of the cooperative’s creation, while elections should be held every two to three years to the cooperative’s boards to ensure members have a say in who represents them.

Chehab’s reforms did not only serve the interests of farmers. His policies also put the state back into the driving seat, extending the central government’s reach into social movements that had threatened its cohesion in 1958 and reasserting its primacy. While the National Union for Cooperative Credit was instated as its specialised lending body, and the National Federation for Cooperatives was established as the sector’s official union, Chehab was working hard at the same time to expand the reach of the intelligence services into the unions and to concentrate power in central government.