Executive Summary

Leaked details of the Lebanese government’s latest financial sector rescue plan reveal a disconcerting attitude: the country’s ruling elites and banking sector remain determined to avoid taking responsibility for the financial losses they caused. Instead, they have proposed that depositors shoulder nearly three times more of the total financial burden than any other stakeholder – mostly through having their savings converted from US dollars to massively devalued Lebanese Lira.

As IMF negotiations continue, Lebanese depositors must prepare to lobby for the application of international banking regulatory norms to Lebanon’s crisis. These business conventions were developed in response to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, when public funds were used to bail out private banks, sparking outrage. The regulations operate on the premise that when a bank or other company becomes insolvent, those in charge and those who took investment risks, cannot pass the losses onto innocent parties. This places investors who take higher risks (in search of higher returns) as partial insulators of safer investments if things turn sour.

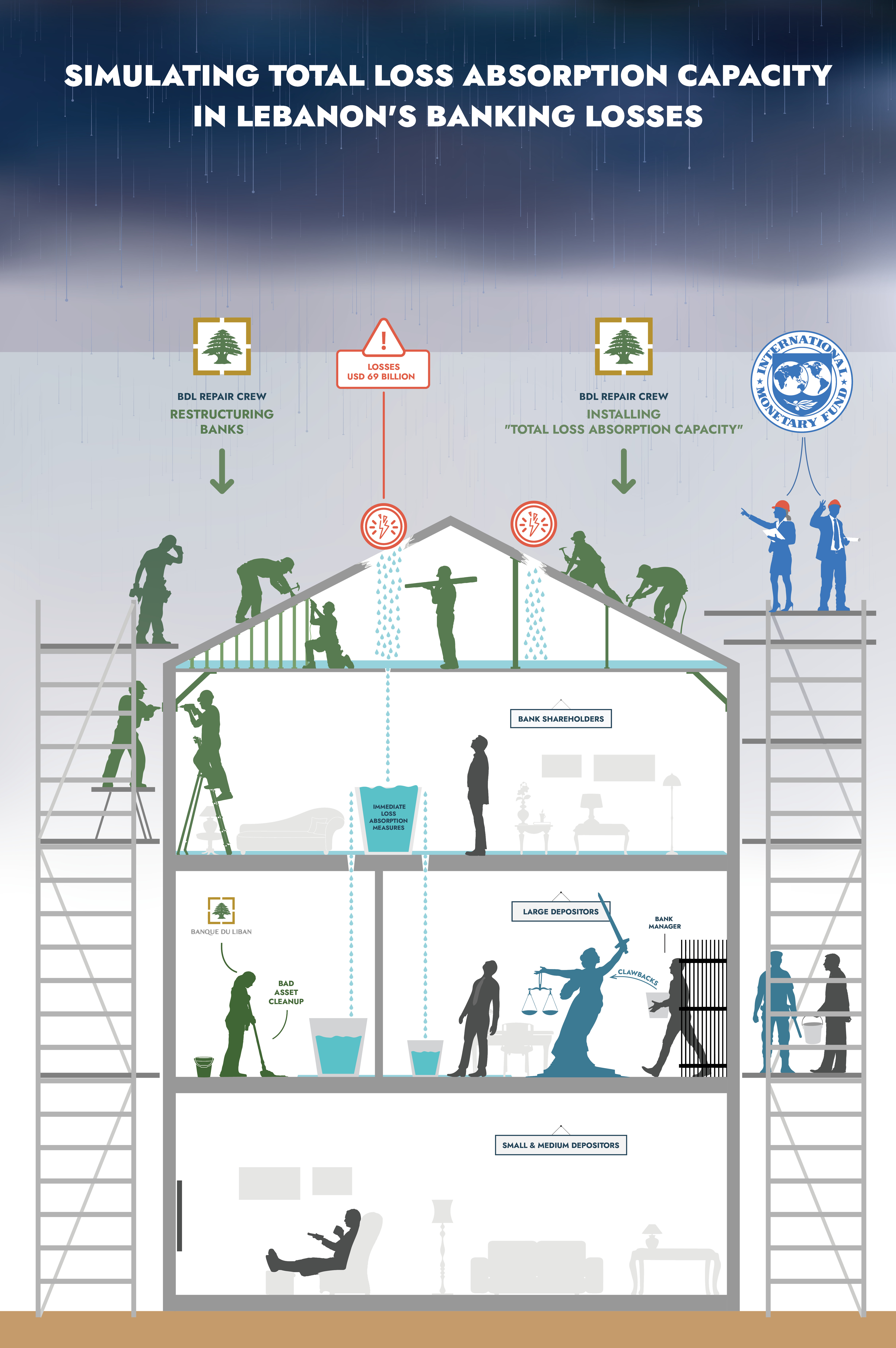

This fundamental premise supports strong arguments for salvaging Lebanon’s banking sector through a “bail-in,” under which losses land most heavily on “insiders” – namely, the banks’ shareholders. Another prominent risk-taker was Lebanon’s central bank, the Banque du Liban (BDL), which oversaw the financial engineering that exacerbated the financial collapse. These parties voluntarily assumed risk in both decision-making and investing, and therefore should be held accountable for the banking crisis.

Unfortunately, Lebanon’s banking regulations do not comply with international standards that would otherwise automate a fair and orderly “bail-in” process. This vacuum has left space for politicians and banking elites to fight back against proposals that would hold them responsible for the banking crisis, and instead shunt Lebanese banks’ enormous liabilities onto thousands of small and medium depositors. Lebanon’s banking regulations also failed to prevent the financial crisis occurring in the first place. Notably absent are rules that properly deal with bank failures, conflicts of interest within BDL’s governing bodies, banking secrecy, and disclosure practices. Over decades, these yawning regulatory gaps allowed prudent checks and balances to be disregarded, in favour of continued, unsustainable profits for banks and shareholders.

Any upcoming deal for an IMF financial rescue package will need to restructure Lebanon’s broken banking sector, which will inevitably involve apportioning responsibility for meeting the sector’s losses. The IMF is also likely to demand the introduction of stringent banking regulations, which will seek to reshape Lebanon’s macro-economic direction and character. These high-stakes discussions will hinge on whether Lebanon’s bankers and political elites will finally accept their responsibility in the economic crisis.

So far, depositors and civil society have not been given a seat at the negotiating table, despite the IMF having a self-determined responsibility to consult with the people their reforms will affect. Lebanese depositors should use these international regulatory precedents to lobby for their rights to a fair distribution of losses, and a shift towards a banking system that protects depositors, meets the needs of domestic clients, spurs local growth, and relieves the national debt burden. Failure to do so could see elites continue to evade responsibility and promote their own interests at the expense of depositors’ life savings.

Global Regulation after the Global Financial Crisis

While Lebanon largely avoided the 2008 global financial crisis (GFC), other countries reeled from the perilous task of allocating enormous losses from their banking sectors. In the United States and Europe, governments faced public outrage – not to mention sizeable state deficits – upon authorising “bail-outs” for banks deemed “too big to fail.” Under these arrangements, distressed banks met their liabilities with assistance from public funds; in effect, this meant that taxpayers contributed heavily to paying off the financial sector’s debts. Understandably, many American and European citizens complained that government bail-outs unfairly burdened taxpayers with the banks’ failures,[1] rather than the banks’ managers and shareholders.

Since the GFC, the international financial community responded to this growing discontent by instituting a suite of regulatory reforms, which aimed to reduce the unfairness of future banking sector collapses. First and foremost, the revised regulations of TLAC and Basel III regulations, developed by the Financial Stability Board (FSB) and Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) respectively promoted conditions for facilitating a “bail-in” as opposed to the reviled “bail-out.”[2],[3]

Under a bail-in arrangement, shareholders absorb the bank’s losses to the greatest extent possible. If this does not cover all bank liabilities, some less senior bank creditors agree to absorb the remaining losses and convert their outstanding debts into equity shares, allowing the bank to recapitalise and recover. Typically, these creditors comprise investors holding a class of liabilities known as long-term subordinated debt.[4] As such, a bail-in tries to ensure the rescue of the banking sector by the creditors and shareholders of the bank itself – as opposed to “bail-outs,” which are funded by ordinary depositors or the taxpayer. This scheme is known as Total Loss Absorption Capacity (TLAC) regulations.

In this way, TLAC regulations facilitate the conditions for ensuring that more conservative investors, such as small and medium depositors, stand less exposed to a banking collapse. Subordinated debt – which provides higher returns than deposits in exchange for the lender assuming more risk – ranks lower than depositor debts upon liquidation during bankruptcy proceedings.[5] By contrast, small-to-medium depositors receive lower yields on investment but should have a more secure position against bank failure. In the event of a restructuring, subordinated debt is converted into capital to recapitalise the bank, thus shielding ordinary depositors from damage to, or use of their, deposits to correct bank’s balance sheets.[6] In this way, the TLAC mechanism ensures that banks have recourse to internal funding sources instead of external ones.

Post-GFC reforms have further protected depositors with clawback provisions, which impose financial accountability on key decision-makers within banks. Clawback rules compel bank management figures to pay compensation for making decisions that did not benefit the bank, even after their tenure is over. In theory, clawback provisions should make bank leaders avoid reckless or illegal behaviour, and instead face severe financial penalties for discharging their corporate duties inadequately.[7] In fact, effective use of clawback provisions offers an additional stream of capital to meet a bank’s losses upon failure, and open to both reducing the financial burden imposed on other debtholders, or at a later stage compensating depositors who faced haircuts as a result of a bail-in.