“Syria is safe. Refugees, go home.”

An ever-growing chorus of countries has been singing this tune since 2019, when Denmark was the first to declare Damascus was no longer dangerous and that Syrian refugees from the capital could return there safely. Human rights experts and NGOs disagreed, pointing out that the Assad regime’s capacity for repression and violence remained intact, and even the European Court of Justice held that EU law prohibited determining only part of a territory as safe for return. Yet this notion of Syria’s “safety” became a convenient fiction that spread to other European states and Middle Eastern governments alike to justify their efforts to expel refugees. To this end, many were increasingly open to normalizing relations with the Syrian regime.

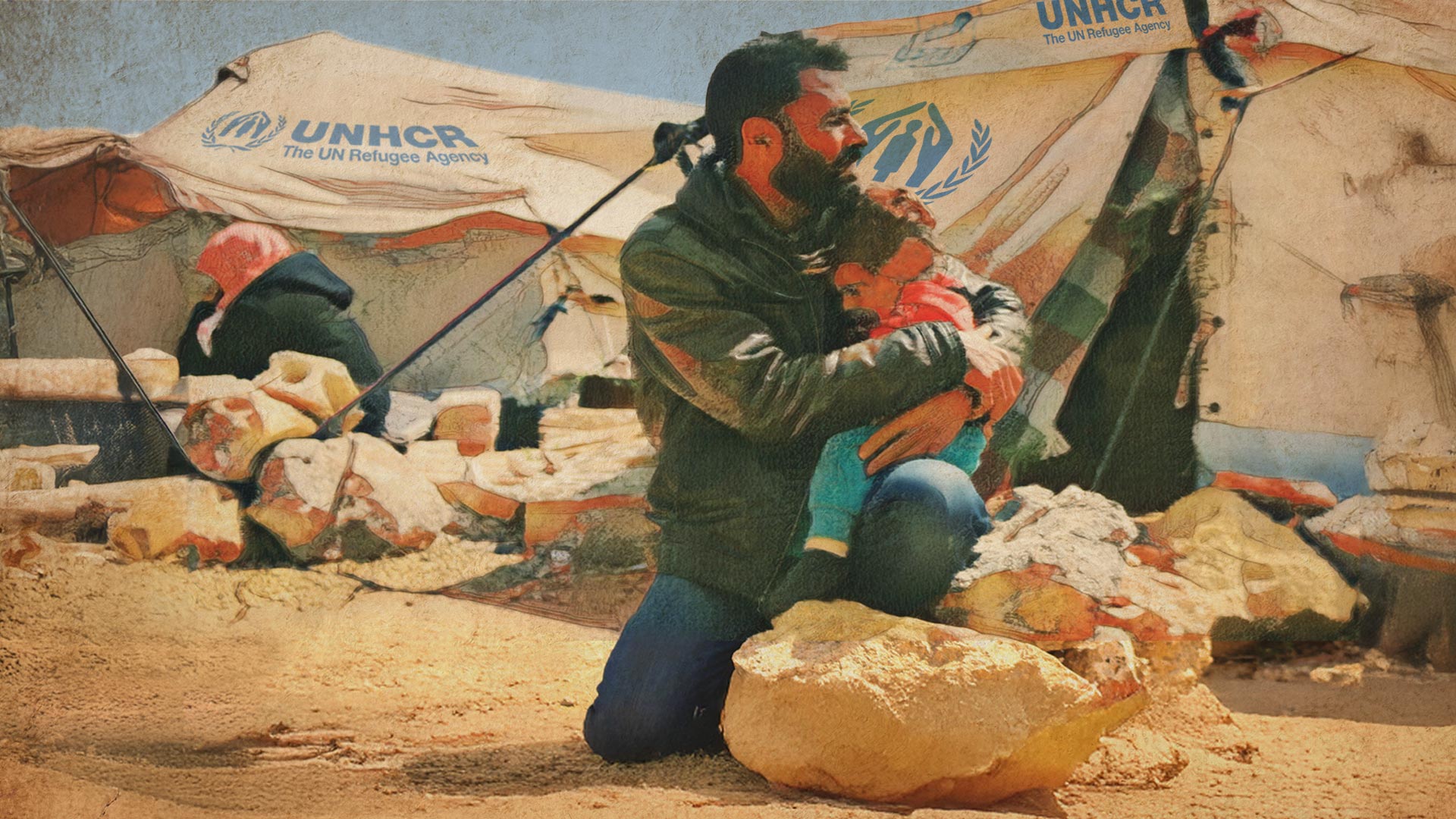

Following the unexpected fall of President Bashar al-Assad in December 2024, Western governments again shifted their stance, this time declaring Syria safe because it was free of his rule. As sanctions against Syria have begun to ease recently, so too have the inhibitions around pushing for mass returns. Yet this perspective ignores Syria’s volatile and unstable conditions that have emerged post-Assad: massacres in the Sahel region targeting Alawites, sectarian violence in Druze communities, a suicide bombing in a church on the outskirts of Damascus, and ongoing Israeli bombardments. These conditions cast substantial doubt on the prospect of whether it is possible for Syrians to have a safe, voluntary, and dignified return – components which the UNHCR considers to be minimum requirements for any refugee return program.