Since 1956, Lebanon’s top legislators have delayed, derailed, and resisted the passage of effective banking secrecy laws that facilitate efficient investigations into financial crimes. That all changed in October 2022 when just before leaving office, former President Michel Aoun ratified a long-debated banking secrecy law. The law is the only IMF prerequisite for financial support to be passed so far. Yet, enthusiasm for its implications is hardly at fever pitch. Even the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has stayed quiet over whether the law is “in line with international standards to fight corruption… investigation of financial crimes, and asset recovery.” And for good reason.

The amended law will allow tax authorities, the judiciary, and administrative authorities access to banking information previously protected by banking secrecy in order to investigate financial crimes. Yet, the final version of the law is riddled with loopholes which indicate Lebanon’s politico-banking elites’ intent to do the bare minimum to pass a law to appease the IMF, who rejected a previous version.

Conflicts of Interest

Per the request of the IMF, the Lebanese Central Bank (BDL), Banking Control Commission (BCC), and National Institute for the Guarantee of Deposits (NIGD) are now able to request banking information. Previously only a sub-branch of BDL could do so. However rather than investigating individual accounts, Lebanon’s top banking regulatory institutions will be limited to reviewing items such as bank’s budgets and trying to identify trends in balance sheets. These limitations on BDL, BCC, and NIGD to ‘general’ investigations significantly weaken the law.

Even though the IMF specifically noted the need for operational independence to be granted to the BDL, BCC, and NIGD, their access to information will be defined by ministerial implementation decrees, first by the finance minister and then by the Council of Ministers, Lebanon’s cabinet. The current caretaker Minister of Finance, Youssef Khalil holds close ties with Lebanon’s banking sector. Khalil worked closely with BDL governor Riad Salameh as a senior BDL officer and allegedly participated in structuring the ‘financial engineering’ scheme which brought down Lebanon’s financial house of cards.

Caretaker Prime Minister Najib Mikati and his brother Taha Mikati are also reported to own stakes in Bank Audi. Caretaker Prime Minister Mikati was also charged with illicit enrichment for making illegitimate gains by obtaining subsidised housing loans. The charges were later dropped based on a “different procedural argument” and not through a thorough investigation into the case’s merits, according to Legal Agenda.

Contradicts Civil Law

Banks can also appeal requests from the BDL, BCC, and NIGD through judicial authorities. This may significantly delay investigations and alarmingly contradicts the country’s existing civil law. During the appeal process a case is brought forward to the Judge of Urgent Matters, who adjudicates on disputes that must be addressed promptly. A verdict will then be deliberated in accordance with the “Orders on Petition,” as per the country’s civil law.

The confusion swirls around whether the existence of an appeal suspends the investigation and access to information or not. Under the Orders of Petition, civil law specifies that the appeal process does not suspend the investigation. However under the banking secrecy law, the investigation and access to information must be halted until the judge delivers a verdict. The contradiction between the civil and banking secrecy laws not only adds complexity to the progress of investigations, but could lead to political interference in the judicial process through subjective interpretations of the laws. Moreover, the contradiction could be appealed as incoherent and lead to contestations of the law itself.

A Rigged System

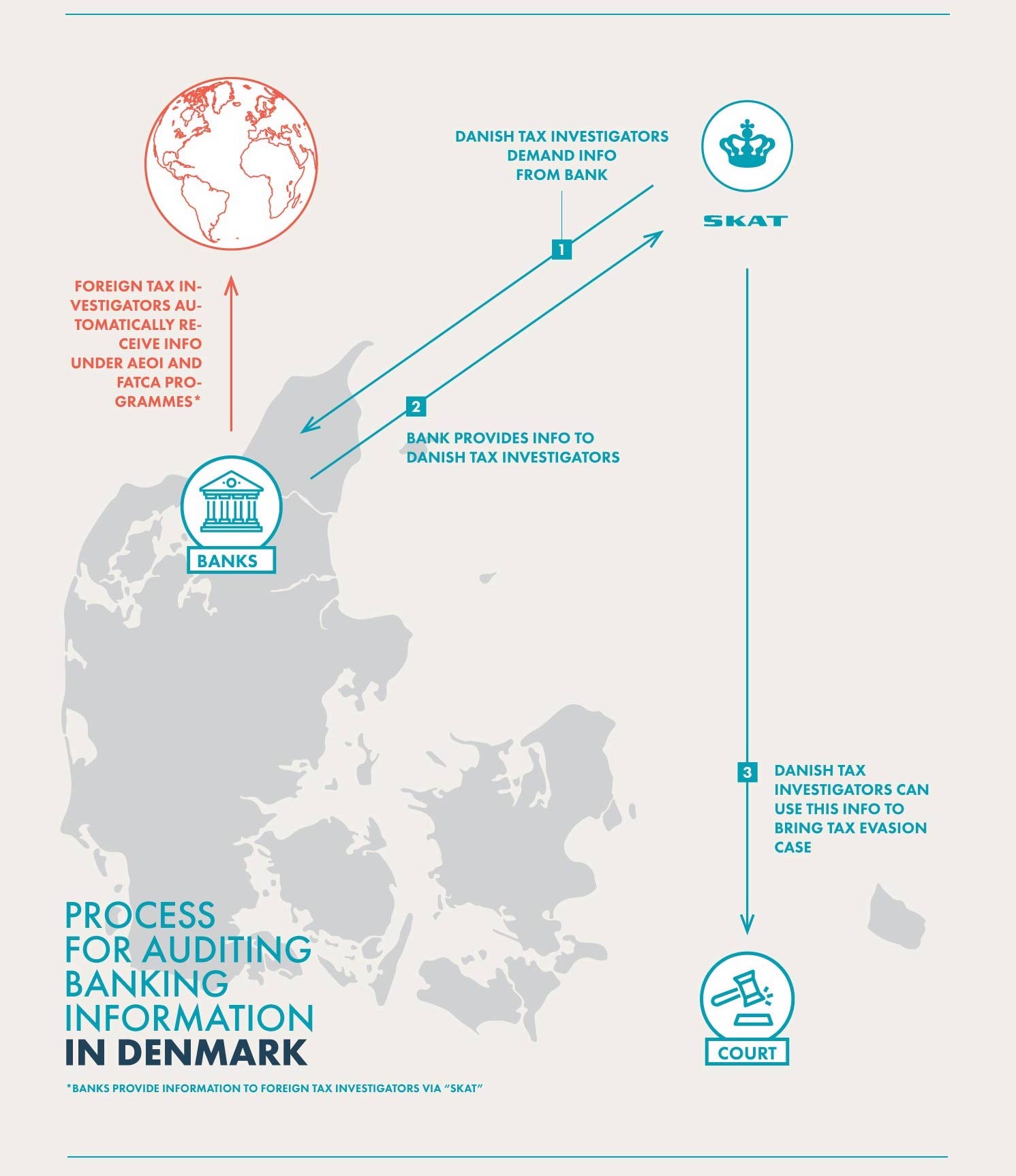

While the adopted amendments provide the judiciary with access to individual bank account information there remains a glaring and seemingly intentional omission. Judicial authorities can only access banking information if there is an ongoing criminal investigation. To open a criminal investigation a case must be brought forward by the public prosecutor, yet the law does not grant the public prosecutor access to banking information. In transparent and internationally compliant systems such as in Denmark this is not the case (see infographic below).

Thus, the public prosecutor’s hands are tied when it comes to investigating financial crimes. Without access to banking information, the evidence needed to investigate and open a case will be severely hampered—which was perhaps the intention of the lawmakers in the first place.

One step forward…

While the current law makes inroads into addressing Lebanon’s moribund banking system it does not advance Lebanon closer to real accountability. Reforming banking secrecy is not just about financial crimes. Banking secrecy legislation is intimately linked to bank restructuring, capital controls, tax reform, capital flight, asset recovery and clawbacks on banking executives’ bonuses. The only question that remains is whether the world’s lender of last resort recognises the law will do little to pry open Lebanon’s chamber of banking secrets once and for all.