After at least 15 years of procrastination, Lebanon’s first-ever comprehensive competition legislation was finally signed into law by President Michel Aoun last week. The law, which civil society groups and the international community have demanded for decades, purports to liberate Lebanon’s private sector from control by politically connected cartels.

Ideally, a strong competition law and regulatory authority would ensure that new companies do not face unfair barriers to entering Lebanese markets. Unreasonable barriers include collusion amongst cartels to fix market prices, dominate access to government permits, and manipulate supply and demand. An ideal commercial environment allows businesses to compete to deliver products that are cheaper and higher quality – lest they lose customers to a rival company.

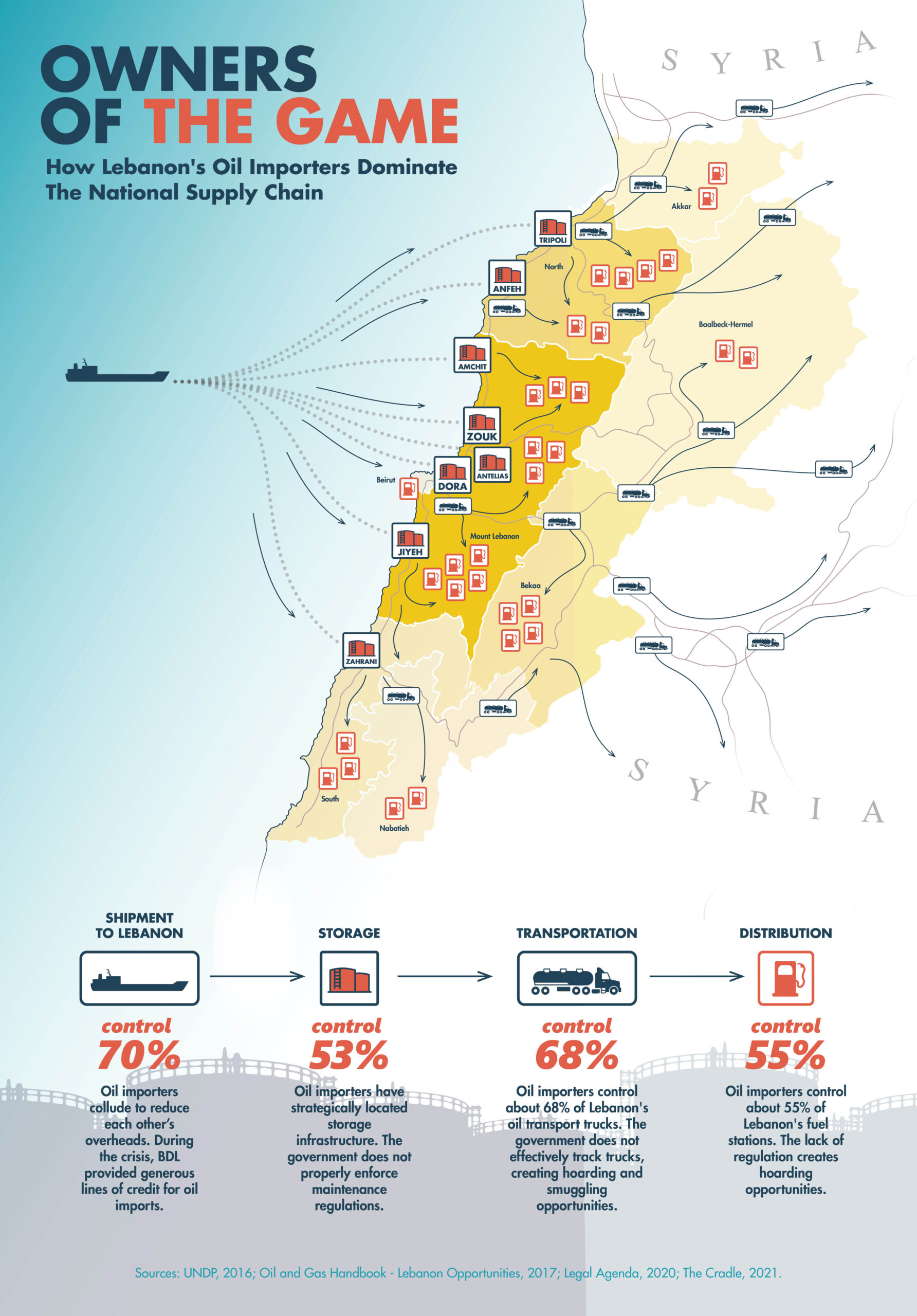

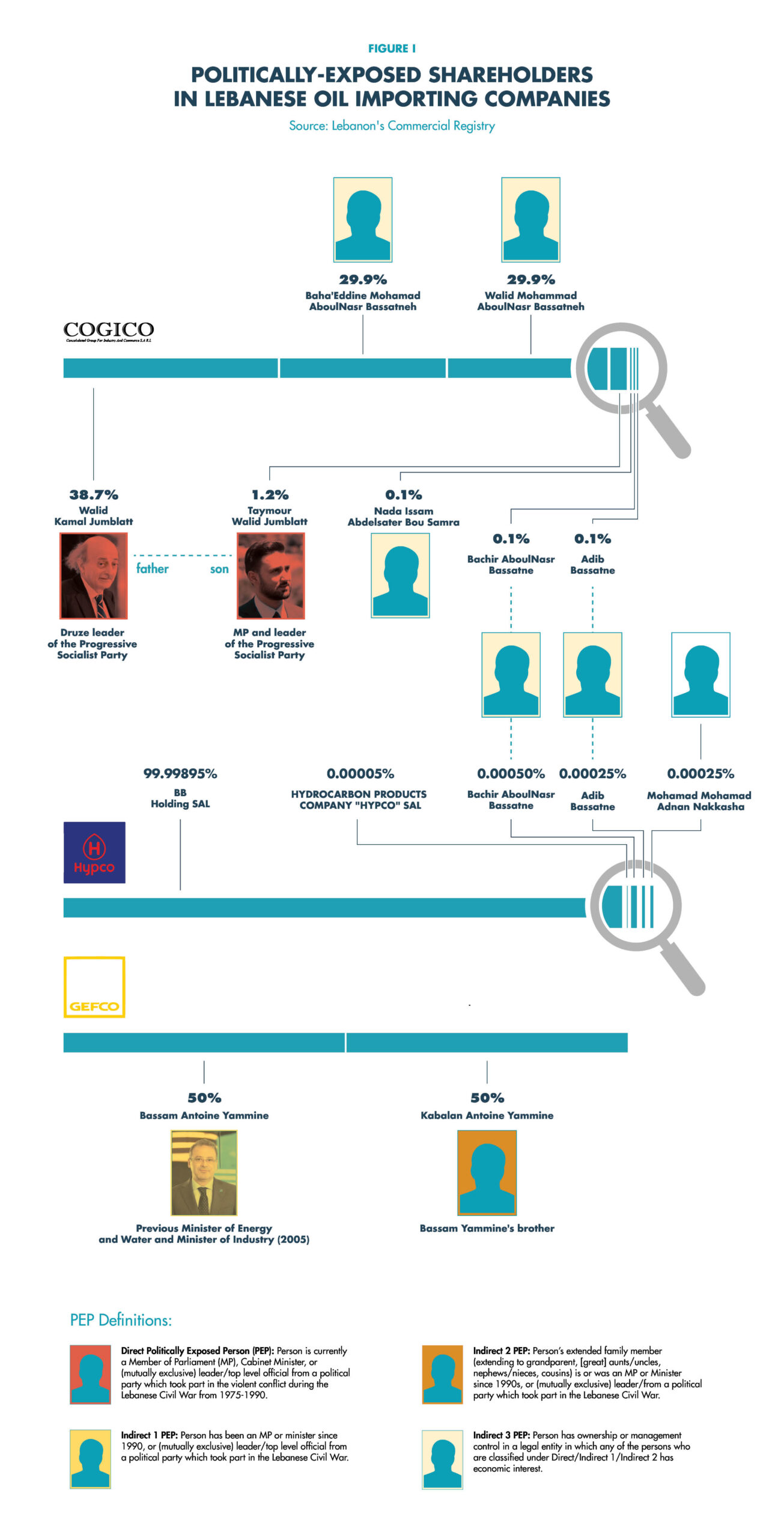

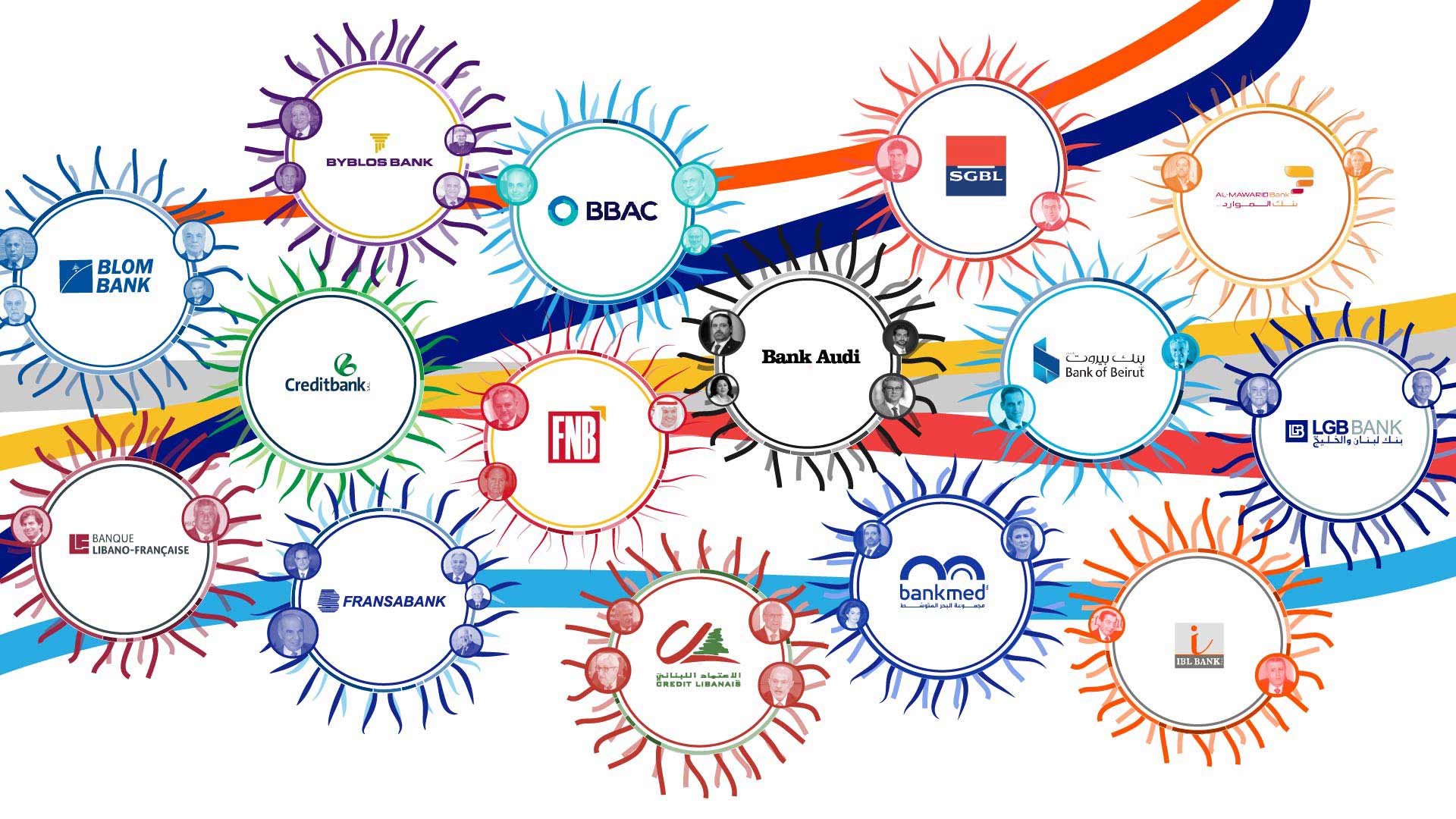

This scenario has not existed in Lebanon for many years. In 2003, the country’s latest comprehensive market competition study found that half of Lebanon’s domestic markets are either monopolistic (dominated by one company) or oligopolistic (dominated by several companies). Free from proper competition regulation, these commercial groups have worked together to maintain high prices for products as disparate as fuel, cement, and potatoes.

Aware of these realities, parliamentarians hailed the competition law’s enactment as a new chapter for Lebanon. Yet these public comments are mainly intended for foreign rather than Lebanese ears, according to Myriam Mehanna, a lawyer and senior researcher at Universite Saint-Joseph de Beyrouth.

“There has been pressure on the Lebanese authorities to pass the competition law since the 2000s,” she explained. “It is a major condition of the International Monetary Fund and major nations […] to show that (Lebanon) is serious about reform.”

Unfortunately, Mehanna holds out little hope for improved market competition under the new legislation. “If anyone manages to get even one indictment (for anti-competitive practices), it will be heroic,” she predicted.

A (kind of) independent regulator

Considerable doubt looms over the National Competition Authority, which Article 25 tasks with “monitoring free market competition” and “supporting the competitive performance of markets.” Most countries rely on regulatory authorities to enforce competition laws; but doing so requires independence from political interference – an asset that the National Competition Authority will probably lack.

Mehanna highlights the membership requirements for the Competition Board, which leads the National Competition Authority’s operations. The competition law reserves places for judges, lawyers, and even members of the Chambers of Commerce, Industry, and Agriculture – but not for Lebanon’s long-suffering consumers.

“There is no seat for a consumer rights expert, but [the competition law] gives seats to the Chambers,” Mehanna stressed. “And we know whose interests they have defended over the past 30 years.”

Instead, appointments to the authority will have to be suggested by the competent minister—that is the justice minister for judges and the economy and trade minister for chambers. Then the cabinet, with all its infighting, will appoint the members of the authority. And there’s a catch: appointments need to come from either the director general level of the competent ministry or one occupational grade lower—positions that are customarily the result of sectarian horse trading between traditional powers in Lebanon. To boot, the authority itself will not be able to get off the ground until it is fully funded through a specific allocation in the national budget (which has yet to be passed), or foreign funding for its activities. Only then, can the authority start its work as the ‘independent’ regulator of competition in the country.

Fellow lawyer Zeina Jaber highlights the National Competition Authority’s institutional status as a glaring opening for political steering. Article 24 places the regulator under the ‘tutelage’ of the Ministry of Economy & Trade, to which it must report to. That said, while the authority must report to the ministry, in theory at least, the ministry cannot veto its decisions.

“It looks independent, but technically it is not,” argued Jaber. “We already have a lot of examples of bodies being led under the tutelage of ministries.”

In this sense, the new regulator faces the same independence crisis as the Consumer Protection Authority, which also operated under the Ministry of Economy & Trade’s tutelage. Throughout the Consumer Protection Authority’s existence, the body has struggled to secure funding and effectively break anti-competitive behaviour by Lebanon’s cartels.

Ink cannot change history

The new legislation does create basic offences for anti-competitive practices and agreements, which involve companies abusing a dominant position in the relevant sector, price fixing, stockpiling, collusion on government bids, obstructing products from entering the market, and exchange of sensitive information. Yet the market’s current structure suggests that the National Competition Authority will need dogged determination to make true inroads into Lebanon’s cartel-ridden economy.

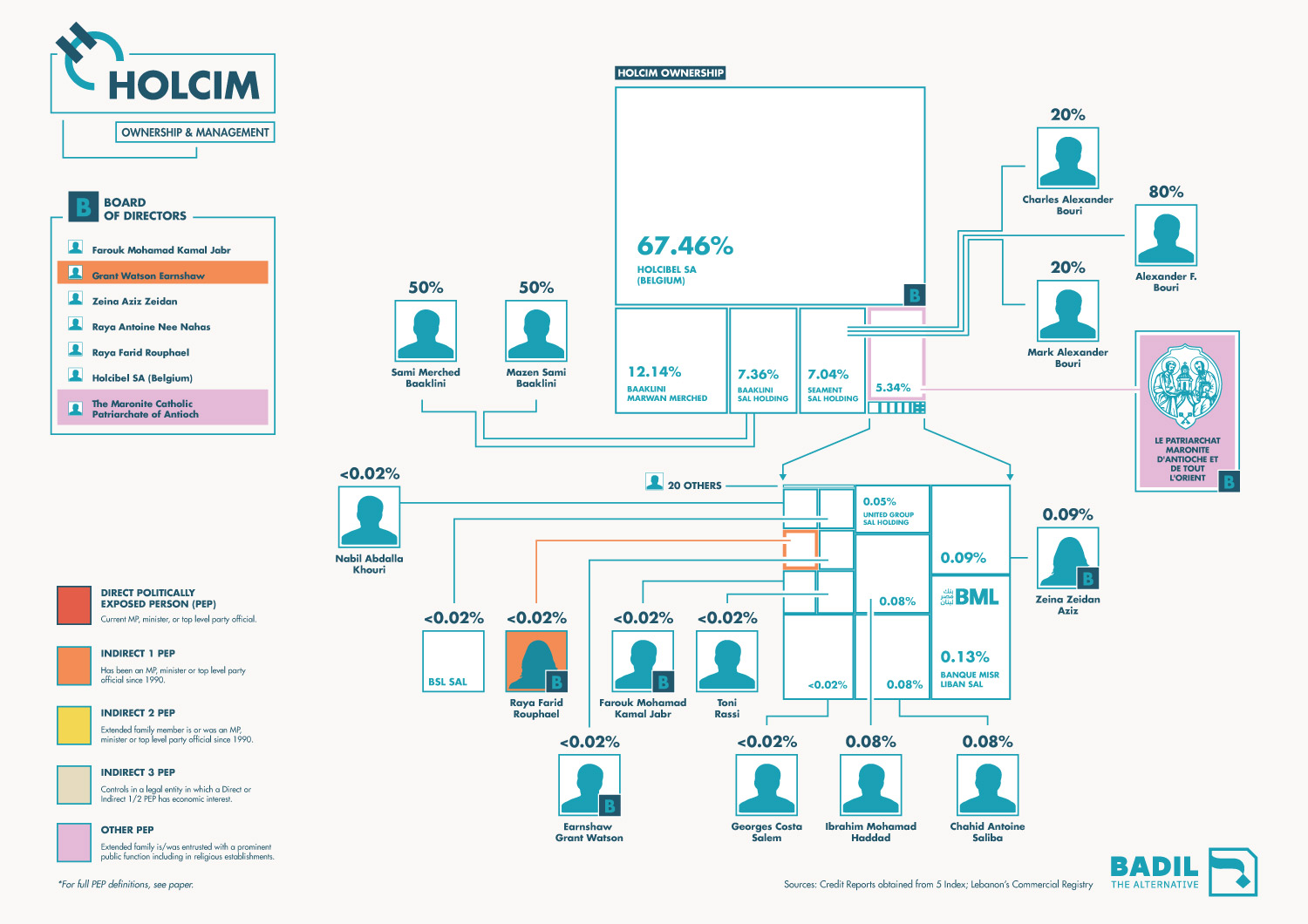

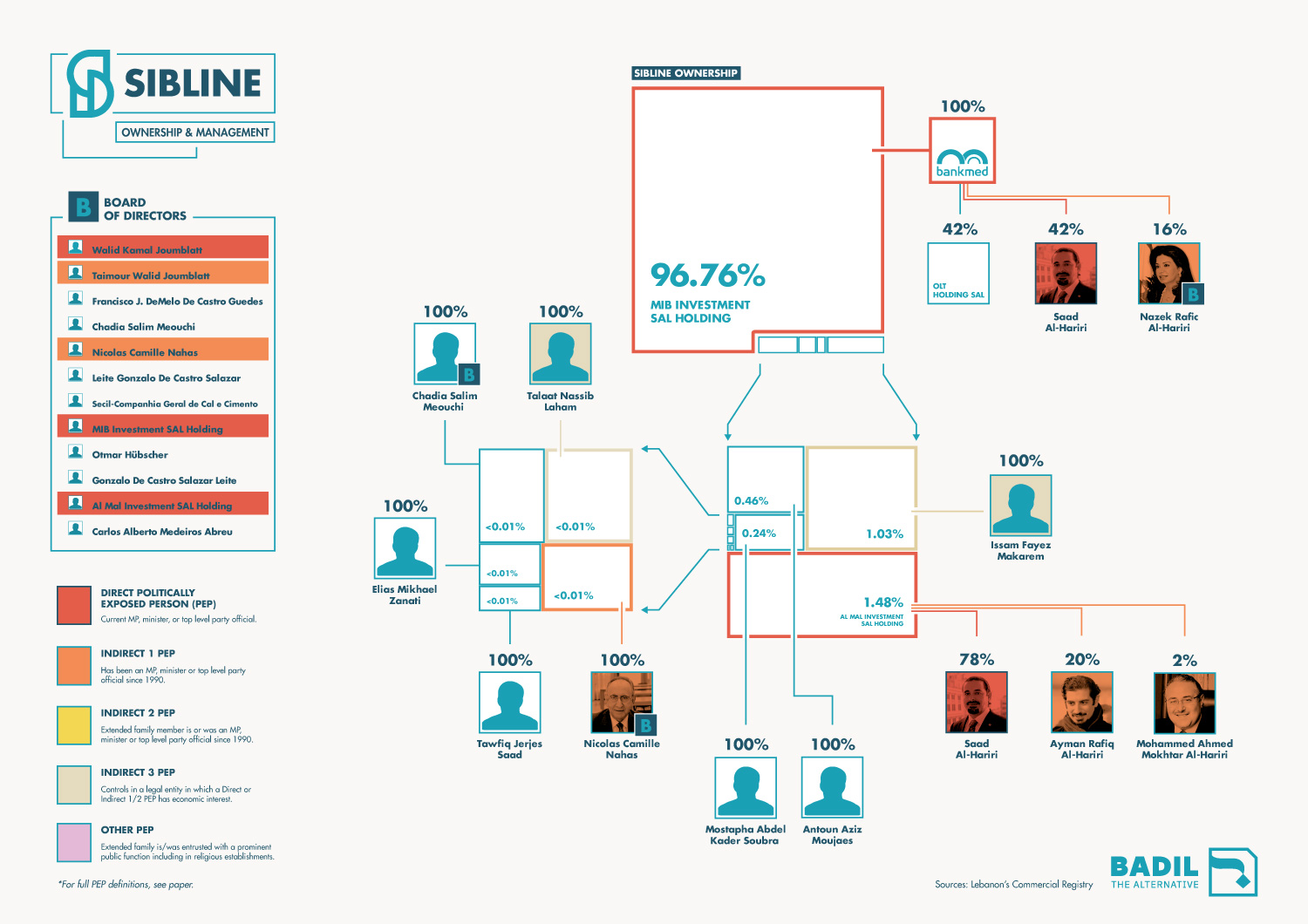

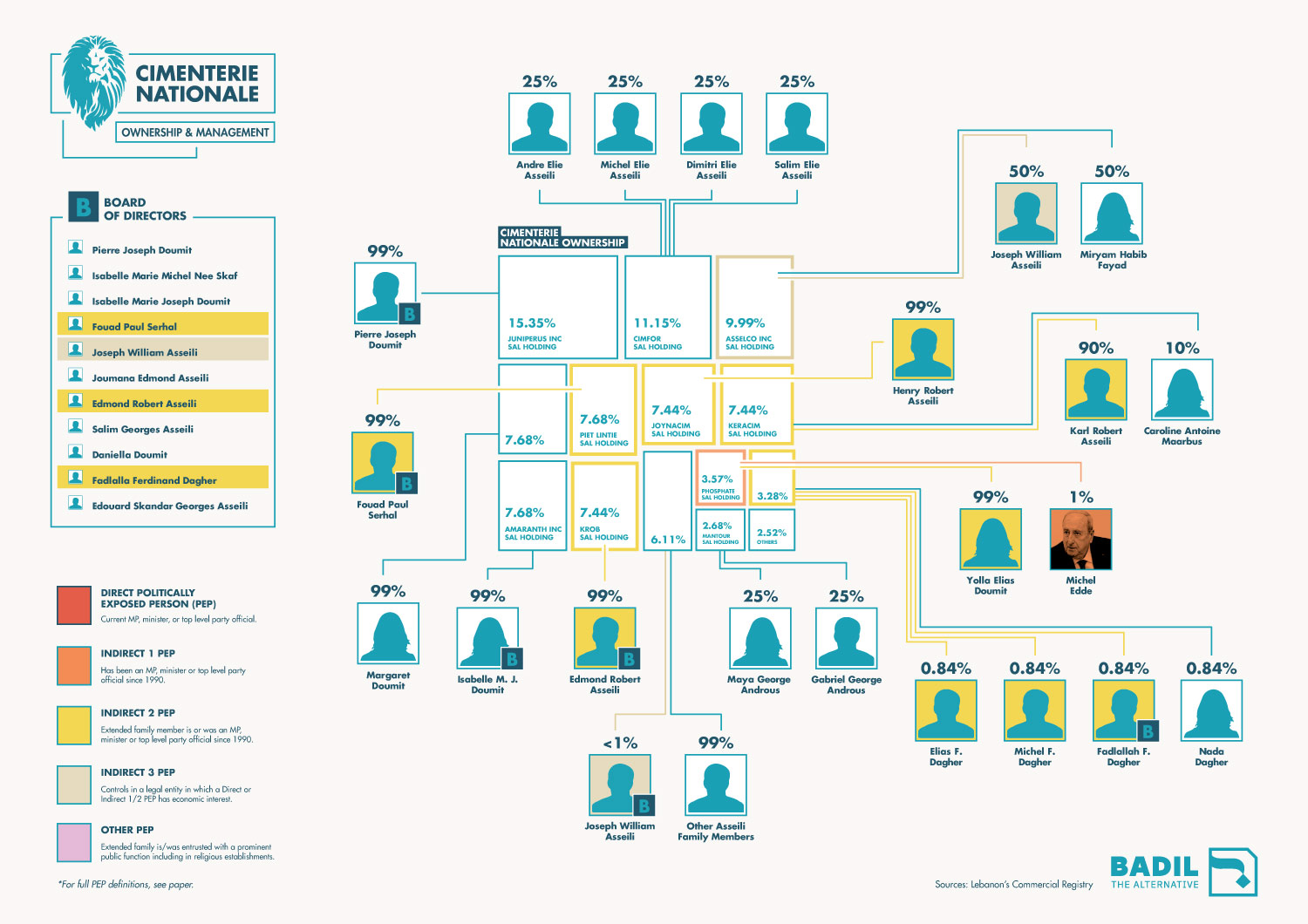

Zuhair Berro, head of the Consumer Protection Association, highlights the challenge’s enormity through Lebanon’s cement production industry. Over decades, three companies have controlled the Lebanese market, enjoying exclusive access to government permits and benefiting from high tariffs that block competition from foreign producers.

Under the new legislation, Lebanon’s three cement cartel members clearly control over 40% of the market – an illegal “dominant position,” as per the law. Yet forcing the companies to comply with the competition law will be another matter entirely, given the cement cartel’s deep ties to Lebanese politicians.